Our last kit review was a barely concealed fanboy rave. This one is going to be more…mixed. Today, we’re looking at the infantry of the army of House Lannister, from Game of Thrones. I find this design very interesting, because the concept has some clever historical precedents, but much of the context and content is mismatched and the practical execution of the concept is quite poor.

This is going to be a long one – it’s not that there’s so many things wrong here (there’s really one main problem which infects the entire design, which is then executed poorly), but because explaining why this is a problem takes a bit more time.

As before, we’ll start by looking at the possible historical models for the kit (the historical basis) which will give us some grounds for comparison. Then we’ll look at armor, weapons and other equipment.

Historical Basis

Let’s be up-front with the main problem here: the Lannister army is a pastiche of elements from across the Middle Ages and Early Modern period, which are not mutually compatible. I don’t have a problem with combining elements from different periods of cultures, but some care has to be taken so that they make sense together. We’re going to see this dissonance in the very nature of the Lannister army, as well as the equipment they use. This arises from the same place as the problem of saying Game of Thrones is ‘medieval’ – which Middle Ages? The European Middle Ages cover around a thousand years of history (c. 450 to c. 1450 or so), to which must be added the first century of the Early Modern Period (c. 1450 – c. 1550), because without that, you don’t have the quintessential knight in high Gothic or Milanese armor (pedantry note: these historical periods are very rough and scholars of both periods argue about where the rough period-breaks ought to go between the late medieval and the early modern). For instance, the knights that guard the famous Arms and Armour room at the MET – often used visually as a shorthand for ‘medieval knights’ (which I used as a shorthand for medieval knights, because they are so recognizable) date to the 1540s – which is to say almost a century after the Middle Ages had ended.

A thousand years is a long time and so it is not surprising that medieval warfare changed a lot during that period. Equipment changed, but so did organization and the structure of armies. The character of the armies changed – knights as we understand the term, for instance, don’t really exist before the 8th century (there were mounted horsemen, of course, but the social and institutional structure of ‘knighthood’ is a product of the Carolingian and post-Carolingian world (read: post-750 or so)). By 1550, knights still existed, but had rapidly sunk into military irrelevance, eclipsed by professional infantry.

(If you want a better sense of how vast this period is, I really suggest Knyght Errant’s video here. It’s a good visualization and accessible discussion of the vast chronological scope involved.)

So what is the structure of the Lannister army? From the dialogue in the show’s early seasons, much of which derives from the books, this is actually fairly clear. Armies in Westeros, including the Lannisters, are not standing forces. Small standing military forces, like the King’s Guard, the Gold Cloaks and the Night’s Watch do exist (along with small military retinues around important nobles) but these forces are all far too small for true open warfare. Whereas the armies of the major houses can number in the tens of thousands, there are only two thousand Gold Cloaks and less than a thousand in the Night’s Watch.

The real armies are formed by ‘calling the banners.’ A major noble calls on his ‘bannermen’ (subordinate noblemen) to come to war, and those noblemen also raise local forces from their own areas as personal retinues. The army in the field is thus a retinue of retinues. In turn that means each bannerman is responsible for an irregularly sized chunk of the army – the expected contribution of a bannerman would vary depending on the size and wealth of his holdings, so the size and constitution (how many of each kind of troop? how well trained?) of these units will differ wildly, even within the same army.

This form of army is very much historical, having strong precedents in (for instance) the French and English armies of the 13th to 15th centuries. Such systems have some advantages (limited administrative overhead, low cost), and some severe drawbacks. One such drawback that concerns the infantry is that very little of the infantry of such an army will consist of professionals. Most of the real professionals – knights and men-at-arms (professional warriors without nobility or knighthood) – will be on horseback. Because the infantry unit is drawn together only for a given war or campaign, there is little time to drill them or build unit cohesion.

There are also sharp organizational challenges. Retinues of this type will be inconsistently sized, as noted, and belong not to the overall army leader, but to the individual retinue leader who raised them. That makes it even harder to get the sort of uniform, drilled infantry that performs well on the battlefield. It will be little surprise then, that the infantry of armies of this sort generally performed poorly – that was part of what made the knight so successful in his hey-day: there simply wasn’t a lot of effective infantry around (in Europe – there was plenty in, say, China). In short, we might expect the Lannister army to look like this:

Note how each man’s equipment is slightly different – different kinds of helmets, colors of gear and shields, some with different weapons. The artist here has probably understated the amount of variety present.

That said, these are the huscarls – the personal guard – of the king. These men are an elite force, which is why they are almost all mailed.

That’s what we are told to expect from the Lannister army. But what do we see?

Also: I thought Highgarden was wealthy – where are all of the farms? Is the Tyrell fortune in sheep?

The units of infantry are uniformly sized and (within each block) uniformly equipped. Moreover, they are marching in tight, disciplined formation, stepping in time – something that requires drill and training to achieve. The army’s formation is complex, which implies a sophisticated command chain (each of these little units needs its own officers to direct it around the battlefield).

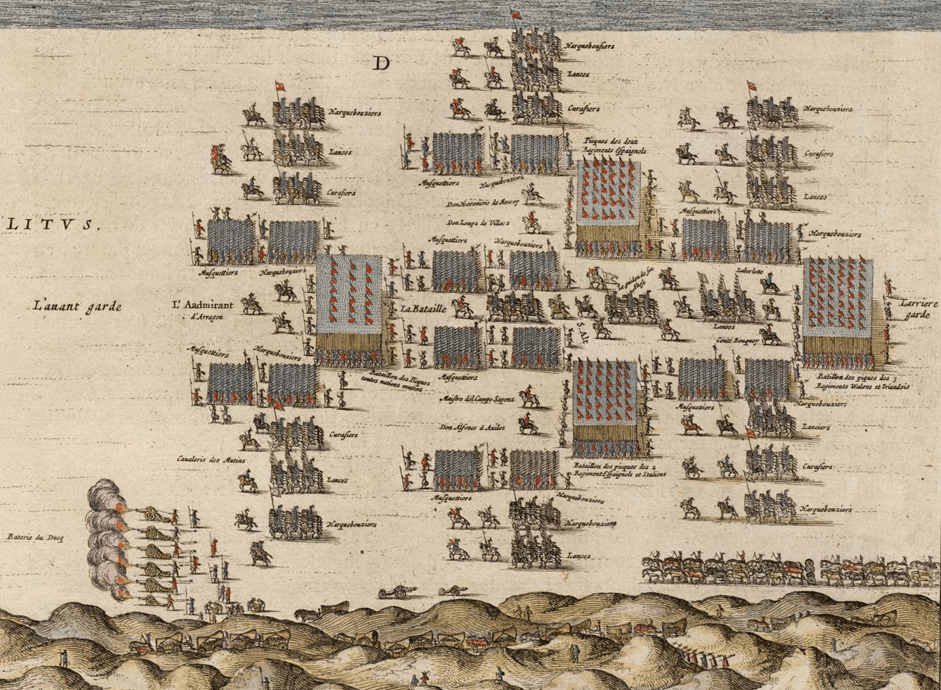

Again, it’s not hard to find the historical inspiration in scenes like this one:

I’m not suggesting they looked at this drawing in particular, but rather at the general style.

Here’s the problem: that is a battle in 1600, featuring a very different kind of army – making this second kind of army possible took not only reorganization but significant and massive social and political change. The sort of political system in which you ‘call the banners’ cannot produce this kind of army. Think for a moment at what would need to be done in order to do so.

First, the bannermen need to have control of their own retinues removed from them, so those units can be broken up and reorganized into evenly-sized groups (the bannermen will resist this – possibly violently – since these retinues are the basis of their political power). Officers must be found for these new units, which then have to be trained and drilled together. Since your bannermen are no longer paying the bills for this force, you need to come up with the money to do so yourself – and to pay for them long-term so that you have the time to produce quality professionals by way of training. The state also needs to organize the production, manufacture and distribution of uniform equipment (France only manages this in the 1700s). All of those tasks, in turn, require hundreds of literate, expensive bureaucrats to administer.

These are not compatible systems. You can have your bannermen call up their retinues, or you can hire long-service professionals, but you cannot have your bannermen call up an army of long-service professionals (note: this is not to say there were no professional infantrymen in the Middle Ages – there were. But they were 1) not raised this way and 2) not available in these quantities. If you have tens of thousands of professionals, you generally have to train them yourself). As we’ll see, that incompatible incoherence extends to the rest of the kit: the show cannot decide if Lannister men are like an 11th century Anglo-Saxon fyrd (or a 14th century English retinue), or if they are actually 17th century professional pikemen.

We can thus also answer the inevitable objection of, “maybe Tywin built the first professional early-modern style Westerosi army.” He clearly didn’t. Large parts of the Lannister army are demobilized and sent home when wars are over, and we hear repeated references to temporary and militia forces. That is clearly incompatible with a standing army of professionals. The simple presence of the bannermen and their role in the early seasons functionally rules out such a change. I should note – this is a problem almost entirely created by the show and does not seem to happen in the books, where the Lannister army behaves largely like we would expect a well-run medieval force (but Tywin maintains a close hold on it because he is politically shrewd).

As a final sidenote before we move on to the kit – this failure extends into some of the plot of the later seasons. Early on, while the show still has the books to rely on, we see many of the bannermen and kinsmen that Tywin Lannister relies on to marshal his forces. We see his need to manage minor houses and knights (like the Cleganes) in order to maintain control of ‘his’ army. In contrast, once the show leaves the books, the Lannister forces begin behaving like mercenary professionals – there are no bannermen to protest Cersei blowing up a holy site, or murdering her kin (by marriage) en-masse with wildfire (remember: a bannerman’s personal security depends on the trustworthiness of his liege, who has promised to protect him – what idiot would stick with Cersei, who obviously will renege?). Instead, the Lannister army begins behaving politically as if it has been converted into an army of a-political long-service in-it-for-the-money professionals.

Medieval armies do not work like this.

Armor

With one exception (that helmet), the equipment the Lannisters carry all has good historical precedent. However, much of it runs into two main problems: first, poor execution in replicating a historical model and second, the same chronological incoherence we saw above. The Lannisters mix 16th century armor with 11th century weapons.

Note: Pre-modern armies were never this uniform. Not the Macedonians, not the Romans, not 17th century armies.

Now it is fair to ask, “why is that a problem? Why couldn’t these things coexist?” To a degree, that is fair – the date ranges for equipment are generally ‘fuzzy.’ But they’re not five centuries fuzzy. The thing is, weapons and armor respond to each other developmentally. Armorers don’t design armor at random. They are trying to find solutions to current problems (read: weapons) that are common on the battlefield. Meanwhile, soldiers are always looking for weapons that might give them an edge against the sort of opponents they expect to see on the battlefield.

So, for instance, mail armor provided great protection from one-handed cutting swords and OK protection from one-handed spears. As that armor becomes more common, you see in turn the development of anti-mail weapons (arrows with bodkin points, crossbows and maces, along with swords with more pronounced stabbing points). In response to that, you see the development of ‘transitional’ armors (coat of plates, brigandine), which use metal plates to frustrate those kinds of attacks. In response to that, you see the development of weapons (like the rondal dagger) designed to strike at gaps in that kind of protection, which in turn prompts the development to fuller protection (the full plate harness). And in response to that you see the development of war hammers, military picks and eventually guns designed to defeat that kind of armor.

All of which is just to show that armor technology and weapon technology are linked. One can certainly propose a lot of a-historical combinations, but the weapons on the battlefield should be responding to the armor on the battlefield and vice-versa. There might be exceptions for sudden contact with new equipment types, but Westeros isn’t even a full generation from the last major war (and has had lots of minor conflicts in the meantime). As a result, the weapons and armor should be fairly well-synced up.

So where is the Lannister armor coming from? This is actually fairly easy to answer: the costume crew has attempted to simulate what was called Almain Rivet (at least in English). Those English words are archaic, but they mean ‘German armor,’ and here the style of German armor intended is very specific: almain rivet is a kind of mass-produced one-size-fits-no-one plate-armor for the emerging professional infantry (armed with pikes) of the 16th century.

Also – note how the tassets (bottom of the armor) overlap using sliding rivets and (not visible) leather fittings to allow them to articulate

In particular, it was what is sometimes called ‘half plate’ – including protections for the chest (breastplate), shoulders (pauldrons), hips and waist (tassets and fauld) and basically nothing else. The complicated and difficult elements of full plate harness – arms, legs, hands and feet – are left unarmored in order to keep costs down. Such armor was often worn without an underlying layer of mail (mail is always expensive), unlike a knight’s full plate harness from the same period (which generally did have a layer of mail between the gambeson and the plate).

On one level, this fits well: the Lannisters are very wealthy, so it makes sense for them to try to provision their army with mass-produced low-grade armor in order to improve battlefield performance. I would contend that, given the administrative apparatus we see in the show, it is almost certainly well beyond even the Lannister’s resources to so armor their entire army, but it is easy to imagine Tywin maintaining a core of semi-professional soldiers so armored (perhaps in an early stage of transition from a late medieval to an early modern style army).

But the execution of this armor in the show is awful.

What the costume designers seem to have done is used stiff leather and attached thin metal plates to it to create the breastplate and the tassets, and then had the entire thing worn over what looks like a leather biker coat. There are very good reasons armor is not made this way: an arrow or spear-point is going to glance off of the metal plate and into the soft, unhardened leather – and then into you. As I’ve noted before, leather armor does exist, but it is not this kind of leather – cuir bouilli is almost as rigid as a metal plate, and quite thick.

Instead, as you can see in the picture above, the bottom of the almain rivet (the tassets) are made with telescoping metal plates. These are attached by leather straps on the inside (so they are protected from battle-damage), which allows the plates to slide against each other, giving the wearer freedom of movement. Also, I have no idea why the Lannister breastplate appears to be made of four horizonal metal strips joined together. This may simply be decorative (it was common in the 14th century to face a plate cuirass with pretty textiles). Ridges on breastplates are generally made to cause blows to glance off of the surface, which these do not accomplish.

Almain rivet was often worn over a padded jack or a buff coat (or both). A buff coat is a leather body protection, but it is not made of modern tanned leather. The process (called ‘kicking’) uses animal (usually fish) oil to treat the leather, and gave the buff coat both its distinctive color and rough appearance. As you can see from the picture below, this sort of protection is a far cry from the black leather that the Lannisters wear underneath their armor – it is, in fact, not only thicker, but a completely different kind of leather.

Of course there’s another problem here: why on earth is JAIME LANNISTER wearing mass-produced munitons-grade armor? Other knights in Westeros wear full plate harnesses (Brienne does) and they’re nowhere near as rich as Jaime Lannister. At the very minimum, he should have a nice mail shirt covering his armpits and waist under that armor. Why doesn’t his armor include an arm harness? Or a leg harness? I have no idea why the costume team decided to put the key nobles of House Lannister in the same armor as their (peasant) infantrymen.

And that helmet. The Lannister helmet deserves its own post. For now, I’ll say that – I’ve looked at a lot of helmets, running from the bronze age to the early modern period. I have no idea what the historical model, if there was one, was for this design. It almost feels like a cross between a Japanese kabuto and a viking-period helmet (like the Gjermundbu helmet (links), but then it has a barn-door hinge for the eyes, which I have never seen before anywhere and which makes no sense (you don’t need to lift a visor which doesn’t cover the mouth or nostrels!).

Grade: D: the almain rivet is a historical design, but this is an awful execution of it and it is out of place with much of the rest of what we are told about this army. The outfit gets an extra demerit for the overuse of black biker leather in place of proper armor-grade leather and mail.

Weapons

Let’s start with the good news: the basic weapon combination the Lannisters have – a thrusting spear, a kite shield (strap-grip) and an arming sword as a backup is absolutely historical. You can scroll up to see that many of the Anglo-Saxon infantrymen in the Bayeux Tapestry are armed exactly this way. As we discussed in the Unsullied kit review (here), the basic thrusting spear is something the GoT costume team has down.

At some point, I’ll talk about the swords of Game of Thrones, but for now, the basic arming swords they give the extras are fine. As with the Unsullied, they clearly don’t have enough for everyone and if you look closely, only a handful of men are armed with them. That’s an understandable budget limitation and we can easily overlook it and assume we’re supposed to assume everyone has one.

The problem is the interaction of that armor with those weapons: in an environment where plate armor is common, the average Lannister soldier has no weapon designed to actually harm someone in plate armor. Including, of course, another Lannister soldier. As a rule, nearly every society designs weapons, first and foremost, that are effective against itself. A symmetrical opponent, after all, is a familiar, understandable threat and any soldier is far more likely to find himself fighting the same sort of society he lives in than he is fighting a radically different sort of threat (because you tend to fight your neighbors).

Against an opponent in mail, a thrusting spear or a tapered sword (one that comes to a fine point) is a real threat – a thrust with either might split the rings of the armor and penetrate. It takes a solid hit and a fair bit of force to do it – mail armor works after all – but it is possible to split the rings with enough force to wound (see here, for instance, with a spear). Plate armor, on the other hand, is impervious to this. Let me say it clearly: there is no amount of strength which will drive a weapon through a solid, well-made steel plate. Yes, I know people get stabbed or axed through their plate armor in movies and TV shows – including THIS TV show – all of the time. It’s nonsense. A 4mm steel breastplate can stop shots from pistols and early muskets – it has no problem stopping a sword.

So the Lannister infantry are carrying a weapon which doesn’t fit at all with the technological environment their armor implies – if this kind of armor is at all common (and it clearly is, look at the Tyrell infantry in S6), they are woefully under-armed for the battlefield.

The kite shield also doesn’t fit, for a different reason: why carry a great, big heavy kite shield when you have plate body defenses? The reason the Anglo-Saxon infantry I pictured above carried that big shield is that their armor was vulnerable to spears and arrows splitting the rings of their mail. If they were, for instance, subjected to sustained arrow attack, being able to hide behind that big shield was extremely valuable. But the Lannister soldiers are already nearly impervious to such an attack, because of their almain rivet armor (assuming it was properly made). Only their legs and forearms are vulnerable and these are hard areas of the body to hit with any weapon.

This pattern can be seen historically – the emergence of more complete plate harnesses is closely connected with the decline of shields – first of very large shields and eventually of shields altogether (gunpowder also plays an important role in this story – I don’t want to oversimplify). Plate armor, as it covers more of the body, makes the shield’s purpose redundant.

So these fellows need to drop the shield and change from a simple thrusting spear to a primary weapon that can perform the spear’s role and be effective against an armored opponent. The most obvious candidate for this is the pike – a long, two-handed spear (c. 15-20 feet). The pike was, after all, the weapon most commonly paired with the very sort of almain rivet armor that these men wear. The problem with giving them pikes is that pike formations require extensive training and drill which, as we’ve established, House Lannister is almost certainly incapable of providing.

So a better option would be to replace the spear with halberds, along with other similar pole weapons, like the English bill, the Eastern European Bardiche, along with Partisans, Guisarmes and so on (the variety of such weapons is bewildering and fantastic). For true ‘realism’ we ought to see a variety of weapons as individual soldiers (who have probably equipped themselves) might get whatever kind of polearm they could afford, or whatever their lord (the local bannerman) has provided them.

The best solution, in my mind, would be to have the armies of Tywin’s bannermen carrying that sort of variety of polearms and clearly lacking the Lannister-sigil emblazoned almain rivet, but then to also have a core of soldiers in that Lannister armor, with pikes. This would lean again on the implication that Tywin has used his vast wealth to build a smaller, but elite, core of professional infantry to structure his army around (most of which is still fairly low quality levy forces raised by his banners). Alas, this sort of visual storytelling is in short supply.

Grade: C+: These weapons almost work, but belong three or four centuries before the armor we are shown in the rest of the show. In a battlefield filled with full plate harnesses, these weapons would be woefully inaccurate. They are, however, reasonably well executed.

Other Equipment

Let’s start with the obvious one: these guys also have no supply trains (and no the Battle of the Loot Train does not count – that isn’t the army’s supply train, it is loot they are escorting back to King’s Landing. Also, the idea of escorting wagons filled with food the 800 miles to King’s Landing is pure nonsense – the horses pulling the wagons would have eaten all of the food before you arrived in King’s Landing). Despite being lowly infantry, they don’t seem to carry any of their equipment.

Perhaps the scene that most exemplifies the show’s failure on this front is the much maligned campfire seen with Ed Sheeran (confession time: I liked this scene as a character moment). Let’s start with the obvious: these soldiers apparently are carrying no personal belongings and that tent they’ve set up isn’t big enough for any of them to sleep in, much less all of them (there look to be about 8 total). And while they’ve got a campfire, they haven’t any cooking tools – they’re just using a stick as a spit, for instance.

What’s still more baffling is that they have four horses. What are these horses for? It’s made very clear in the dialogue to this scene that these men are common soldiers, not cavalrymen (who almost always came from a higher social class, even when they weren’t knights). They have no cart or wagon for these horses to draw (and you’d quicker use other animals, like a mule, for that sort of thing). For soldiers evidently moving down a major road, pack-horses are a very inefficient way to carry anything. And in what universe do eight common infantrymen rate four expensive packhorses for their gear?

Of course, that raises the second question: what gear? To get a sense of what’s missing, let’s talk about what they might have with a historical comparison to the load carried by a Roman infantry squad. The smallest Roman unit was the contubernium, or tent group, and it was 6-8 men, so it fits this unit size. Each contubernium would likely have had: a single tent which could fit all 8 men, wooden tent stakes, cooking supplies (a pot and spit, probably shared), a cup or bowl (one apiece), a saw, basket, pick-axe, leather straps, a sickle, a large wooden stake for field fortification (one per soldier), a mule-portable hand mill for milling grain (c. 27kg), three days worth of food, firewood, along with any personal possessions. It seems likely (but is not certain) that each contubernium had its own pack-mule (which would have carried some of this gear, especially the hand-mills).

That’s around 20kg per man of carried equipment (not counting arms and armor), plus the stuff carried on the mule (like the hand mill). Now most armies were not so lavishly equipped as the Romans, but some the basics – cooking supplies, tent, firewood, basic tools (especially digging tools), rations, spare clothes – would have been common to almost any infantryman in almost any era.

This is even worse than the Unsullied’s lack of kit, because this is a camp scene. If ever there was a time to get the props crew to clutter up the set with some pots and pans and packs and other stuff, this was it. We spend a long time in this camp (a little more than 5 minutes – fairly long for such a scene) and my local Revolutionary War reenactment troupe does a better job setting up a camp (not intended as a dig on reenactors – just a comparison to what can be done by part-time enthusiasts), and something tells me their budget would be a rounding error for this show.

(Of course, the related problem question: why is a squad of 8 infantrymen without an officer just moving alone through the countryside? Where are these men’s bannerman lord? Or officer? Is one of these men at least an NCO? The Roman contubernium had its NCO, the decanus. Only a truly foolish military commander would let his squads of infantry just roam the countryside without direction – you’re likely to end up without either an army or a countryside that way.)

Finally, the red Lannister cloak. I think, for soldiers sitting in camp, this is a great touch. A well-made, thick woolen cloak is awesome. It repels water, keeps the cold out. The problem is that we also see them wearing this cloak into battle. This is a common trope in fantasy settings because a cloak almost looks like a super-hero cape, but as battle-wear it is far from ideal. A good cloak is somewhat heavy, but more importantly it provides any enemy an easy way to grab on to you and put pressure on your neck. I cannot recall ever seeing an ancient or medieval warrior wearing a cloak in battle in any ancient or medieval art.

Grade: D+: Again, this category is heavily handicapped because almost every show and movie messes this up, but the addition of a camp scene without a camp pushes this to below-average. I love the cloaks, but take them off before a fight.

Conclusions

I think the Lannister kit actually represents, very well, the degree to which the GoT team are largely out of their depth when it comes to understanding pre-modern warfare and run into problems as soon as they haven’t the books to rely on. The basis for this army – established in dialogue and thus reliant on the books – is sound. But the translation of that force into the visual medium is a mess of anachronism combined with bafflingly poor representation of armor, particularly.

I certainly understand the sharp budget limitations for this sort of thing – that’s part of why I didn’t review the even worse looking kit for the Tyrell army we see in Season 6 – those guys are only in a handful of scenes and budget is tight. But even major characters are put in the atrocious Lannister armor (Tywin and Jaime, in particular). This armor gets loving camera close-ups. I can’t help but conclude that the folks on GoT think they ‘nailed it’ with this design.

I think (as before) there was a missed storytelling opportunity here. While the dialogue of the Ed Sheeran camp scene shows us some common Lannister soldiers, we only get that from the dialogue – we are told these are poor, common soldiers. But we aren’t shown it – they wear the same armor as their lords and masters. The costume team could have saved a lot of money if they had put the Lannister men in cheaper, more diverse and more historically accurate armor – for instance, by having many of the men in just a gambeson (it would make that big shield make sense), with perhaps a basic brigandine (which can be convincingly faked on the cheap). We could actually see the contrast between the resplendent plate protection of the elites and the much weaker protection of the poor infantry.

It would also be an opportunity to say something about Tywin. Surely the man who loudly proclaims “a lion doesn’t concern himself with the opinion of sheep” isn’t the kind of man who cares deeply about the survival of his poor peasant infantrymen. Showing a contrast between Tywin’s equipment, the equipment of his elite troops (I really do love the idea of a dedicated core of professional pikemen at the center of the army) and the poor common infantry of the banners would drive home the brutal power imbalance of this society and how cheaply Tywin treats their lives in his endless wars.

Overall Grade: D+: This is a poor kit. The concept has some historical merit, but also serious flaws, but it is the baffling execution of the armor concept which drags it down. For a costume set that is on screen so much, I wish they had done better.

The French Capetian kings had a system whereby they did have a royal army paid for by the king , they maintained an in fact large number of full time professionals ; serjeants and men at arms , and would be able to call a small levy from the towns/cities owing the crown troops (especially with royal commune towns with whom this was a specific arrangement) which would be paid for and equipped by the town or city, these tended to be crossbowmen. The exact numbers of these levies are hard to say as the towns paid for themselves and lots of records were lost in the revolution . The number of these professional royal serjeants and men-at-arms is subject to debate but the number was at least 3,500 across the royal demense from the payment rolls of the castles/garrisons of King Phillip Augustus in his conflict with the Angevin kings. This period was rather a low point for the power of the French kings too, until after Phillip’s conquests that is. Therefore it is entirely possible and with historical precedent that the House Lannister , which has the effective power of a royal house over its own kingdom as well as being obscenely wealthy, has an army whose infantry component was in part a professional force entirely belonging to the house Lannister and in part militia/levies-most likely the archers. It is likely that the cavalry is still feudal , cavalry being more expensive to maintain, train and the quality/retinue cohesion of feudal cavalry being high, therefore they very well can still “call their banners” in a feudal system while having a professional infantry army.

As for cloaks in battle , i have actually seen the odd medieval manuscript depicting an individual in a cloak in battle, but it is exceedingly rare and only ever an individual, i have only seen two such examples. In roman art however it is not uncommon for a number of individuals, on foot or horse, to wear a cloak in a carving or mosaic depicting a battle. Consider Trajan’s column , the Altar of Domitius, or the famous mosaic of Alexander the Great, where he wears a purple cloak while in his armour. It may therefore have been done so there may be some historical precedent.

As for the armour and the rest of this article i largely agree. I think the helmet is some sort of degenerated and strange sallet in its intention, most design choices outside of a few glimpses of normal armoured knights in the first 2 episodes of season 1 have generally been baffling and nonsensical. Though i do find Stannis’s armour interesting.

On paid professionals in the Middle Ages: absolutely they did exist. But I think it is possible to overstate their presence, which in turn does some damage to understanding what is happening in the 15th and especially 16th centuries, when real professional armies begin emerging. Obviously the sergeantry was a very real thing, as were the large mercenary companies of the Middle Ages. There was some professional infantry to be had.

But they were a small faction of the total forces – Philip Augustus’ c. 3,500 total professionals is less than half the size of the army he leads at Bouvines. And most of the long-service professionals are not the core of a uniform field army, but garrison forces holding castles in the name of the king. And that is the key thing here and even later. France recruits a bunch of the English free companies towards the end of the HYW to get them to stop wrecking the place, but the number also only comes to a few thousand (my memory wants to say c. 6,000), which is a far cry from field armies of c. 30,000 as at Agincourt. These sorts of troops existed, but they were a very small part of the total forces available.

By contrast, House Lannister is rolling around with armies 10,000-20,000, which appear (in the show) to *all* be uniformly equipped and trained. This is something quite different and the thing is, we know what kind of organization it takes to begin fielding armies of 20,000 professional infantrymen, because Europe was doing that in the 16th century – it required very different systems of organization and revenue raising. I think the fig-leaf of Lannister gold doesn’t remove this requirement either – consider the problems Spain had paying the Army of Flanders in the 16th and 17th centuries, even with a veritable river of silver and goal coursing in from the New World. We can actually so for absolute certain House Lannister is not *that* obscenely wealthy, because their gold hasn’t produced wild runaway inflation and subsequent economic collapse.

Money isn’t even the end of it. Organizing in that new way created all sorts of command difficulties, since doing so disintermediated the feudal nobility that had previously done the job (the solution to this problem being the captains and colonels – essentially private military contractors – of the 16th and 17th centuries). Standardizing equipment came still later (18th century in France) and required an entirely new class of administrators (the royal intendants) to do it. It’s actually a lot more involved than hiring a few thousand mercenary sergeants.

On Cloaks: Trajan’s Column – as I recall, the cloaks there are on cavalrymen not actively engaged in combat. They may well be traveling cloaks. Altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus: the equites wears what looks like a sash, not a full cloak. This is also not a combat scene, but rather a lustrum – a political/religious ritual. Alexander Mosiac – he’s clearly got something. I’ve always read it as a short cape or scarf, rather than a long cloak, but given the damage to the mosaic, it could be anything. Working by analogy from non-European cultures (e.g. Japanese horo), if anyone is going to wear billowing capes or cloaks, it will be cavalrymen and not infantrymen, so the point on the Lannister infantry still, stands – wouldn’t you agree?

If you want to see what it takes to field large armies of semi-professional infantry and cavalry, you can look at 10th century Byzantine army. This would be Byzantine infantryman btw:

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/e3/45/2b/e3452b5e9df16b6c1302be9ff358031b.jpg

Hi, loving this blog so far. One thing well we’re being pedantic: unlike the modern name Jamie, Jaime Lannister’s name is spelled with the i before the m.

Fixed!

Great article. I would argue that a cloak’s weight is more of an impediment than its grab-ability. If an opponent is behind you, close enough to grab your cloak, he can already kill you in several ways. Whereas any weight *not* worn in combat is a big endurance bonus.

and they really get in the way of your arms ( both kinds)

Bret, here are some belated proofreading corrections, if you’re interested at this remove:

formation is complex, with implies -> formation is complex, which implies

cannot decide of Lannister men -> cannot decide if Lannister men

“maybe Tywin build the first -> “maybe Tywin built the first

conflicts in the mean time). -> conflicts in the meantime).

failure on this front of the much maligned -> failure on this front is the much maligned

quicker use a other animals, like a mule -> quicker use other animals, like a mule (delete first a)

bowl (one a piece) -> bowl (one apiece)

Fixed!

This was a great read, but I thought I’d make note of something. Throughout the seasons – most notably Blackwater in Season 2 and the Casterly Rock siege – we do appear to see Lannister extras who’re wearing far less expensive equipment (although they never truly ditch those horrendous helmets, save the archers). There doesn’t really seem to be any real consistency to this, as the plate-wearing soldiers pop up amongst as often (including the Battle of of Oxcross leadup) but they at least exist.

https://i.imgur.com/r1MtpYw.png

https://i.imgur.com/r1MtpYw.png

Budget constraints or them actually thinking this through? My bet’s the former but who knows.

Probably to emphasize the Lannister’s best-known character trait, their humility. Tywin isn’t the sort of lord who’d wear crimson-enameled plate with gold-and-ruby lions for pauldrons holding a massive cloth-of-gold cape that draped over his gold-armored horse.

Granted, that ornate of armor might be beyond the budget allotted for the show’s armory (HBO aren’t literal Lannisters), and it might look a little silly in live-action, but dang if Martin didn’t know how to express the class differences in Westeros through his descriptive prose.

A note on armour-grade leather, for those not in reenactment: find a good pair of shoes made entirely of leather. Look at the soles. That’s about *minimum* thickness for armour grade, and soaking these in boiling wax renders them pretty much entirely rigid, at least in ambient temperatures under 30 Celsius.

Which is one reason cuirbouilli is rare in places that routinely hit those temperatures.

Just a thought, but could Lannister helmet be inspired by a combination of helmets? For example, Gothic plate harness had a helmet – sallet – that covered only upper head, leaving the mouth exposed:

https://www.armorarena.com/image/cache/catalog/products/plate-armors/helmets/german-gothic-sallet-helmet-ver-2(3)-1000×1000.jpg

Of course, in the full plate harness, this helmet was worn with bevor, so that it would cover the entire face. But it was not unheard of for bevor to be lowered (for example, to allow for easier breathing and better vision in close combat). Light infantry also often worse just the sallet, with rest of armor being gambeson.

Visor meanwhile looks kinda like the Japanese kabuto:

https://static.turbosquid.com/Preview/2019/10/06__05_04_38/Kabuto_001_001.jpg1947FAA2-A2BE-44EB-8D90-5A47AFFF1B00Large.jpg

It is somewhat worth noting that the method of raising levies in GoT’s is better addressed in Fire & Blood, where Martin notes that in Westeros, particularly when it comes to the North, armies are often not expected, or legally allowed, to return home- the absolutely dire circumstances of Westerosi winters (often approaching 20 years without a thaw) mean that it suffers a great overpopulation problem in summer, where it essentially shifts from a series of arctic dwelling hunter gatherer societies into a fertile tropical dwelling society with access to high intensity agriculture.

Now this doesn’t mean the numbers or structures actually work out fully (I still think the summers would be too short to present the size of armies shown in the show from a minimal basis), but it does mean westeros doesn’t really fit historical models, because no medieval society had to deal with the north of their country transitioning from fertile farmlands to a permafrost dominated tundra every other generation. It’s also especially noted that the reason the Starks have been the rulers of the North for so long is that their family seat in winterfell commands… a geothermal spring that they use to grow fungi in a greenhouse, hence allowing the holder of winterfell to emerge from winter with enough men to have any trained guards. The north’s ‘wolves of winter’ are specifically stated to be what is expected of old men and extra sons when the frosts arrive- they ride south (because horses are suddenly a liability) and break things so that they don’t exhaust the food supplies needed for the family heirs and women at home. It also explains, to a certain extent, why the north has remained seperate- for the southern westerosi, advancing north would be suicide, as your people do not know how to survive without agriculture, whilst the northerners being both likely worse at agriculture (they have whole decades where no-one practices it, and won’t be using the same number or species of beasts of burden- breaking the spring ground using dog-pulled ploughs isn’t going to be a match for oxen), and suffering generational out-migrations probably alleviates some of the improbability of about half the country being ‘one people’ without them expanding into the other half (which they do, but those who go south aren’t supposed to come back).

The ten year summer that ends in the first book is noted to be unusually long; ‘decades’ plural is not the thing.

You know, I had the first of your Fremen posts bookmarked (okay, I had it open in a tab) unread for a long time. And I thought, hey, I’m gonna finally read it and clean up my tabs. And here I am, having four more tabs of your blog open. Damn you’re good.

One thing I will say is that I feel a lot of the issues with combining different medieval and early modern eras goes all the way back to GRRM himself in the books. While he has stated many times his main inspiration is the War of the Roses, a lot of the description of weapons and armor is itself all over the place with some characters like Gregor Clegane wearing full plate armour but 12th-13th century style Great Helms or how some of the Lannister guards described in the books also sounding equally as though they would fit in more with Richard I’s army of the 3rd crusade than Richard III’s army at Bosworth. Also Martin really does not allow for much develop in styles, since based on descriptions armour and tactics have remained the same since Aegon’s Conquest 300 years before the series and justified it saying that the presence of dragons prevented developed….an argument that falls apart when you consider that dragons became functionally extinct less than half way through that 300 year dynasty. Also we do get descriptions of the Lannisters especially favouring pikes in the books compared to the show (as well as Stark infantry), where it is all spears and swords. Basically what I am saying is that Westerosi warfare is kind of a mess and while that would be fine, GRRM’s claims to wanting to be “historically authentic” fantasy and also the fandom’s claims to the same make it very dubious.

MUCH older than that. A mishmash of all periods of the Middle Ages PLUS Renaissance and early modern, dished up as “medieval” has been standard since the Romantics.

Excellent point, so much of the aesthetic we think of as Medieval really isn’t.

Is it just me, or is there a resemblance between the Lannister helmet and Uruk-Hai helmets ?

At first I thought it was just the sideways ridge, but on closer inspection, the overall shape is pretty similar as well