This week, we’re looking more at what life was actually like in Sparta, this time focusing on wealth and property. Last time (here), we looked at the question of daily life for women in Sparta and concluded that the oppression faced by the vast majority of women in Sparta – the female helots – far outweighed whatever meager benefits were afford to elite spartiate women. This is part IV of our seven part series on the contrast between the image of Sparta and the reality (I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, Gloss., Retrospective).

As we established back in Part II, contrary to the nostalgia for simpler times that permeates our literary sources, we have good evidence that there were always significant disparities and inequality in wealth and status both between Spartan classes (citizen, free, slave) and within those classes. Whereas last week we saw how sharply that shaped daily life for Spartan women, this week we’re going to zoom out just a touch to look at entire Spartan households – particularly those of the spartiates…and former spartiates.

And as always, a helpful glossary is here, but we’ll define all terms at first reference too, so don’t feel the need to refer to it unless you think you’ve missed something.

The question we are taking on is the notion that Spartan society was particularly cohesive and stable. If I may use Nick Burns as an example – one last time – of this idea out in the wild one last time:

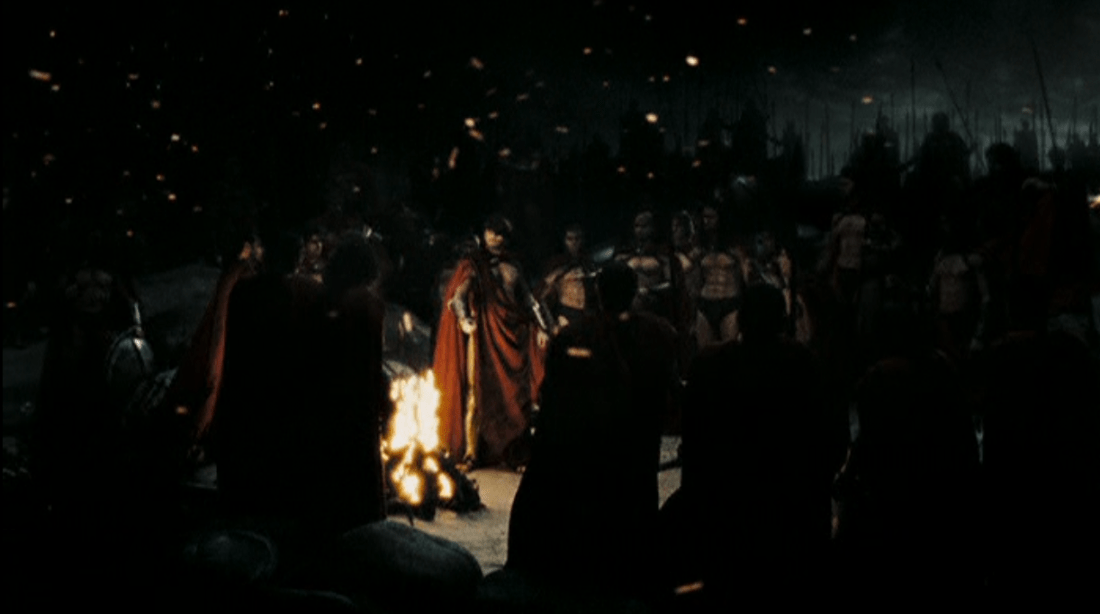

This idea is frequently reflected in popular images of Sparta. The spartiates themselves – perhaps excepting the kings – are identical and interchangeably. They have the same life experiences, the same outlook on the world and the same mentality. This vision of Sparta permeates how it appears in film and games – there is a common ‘Spartan experience’ that lends the extreme sense of solidarity to the Spartans. Of course, we’ve already seen how the very make-up of Spartan society means that only a tiny minority of Spartans partake at all in this common experience – but all too often films like 300 ‘solve’ this problem by simply writing everyone else out of the story.

This often serves as the core for a defense of Sparta – that the system may have been brutal, but it produced a radical leveling that created a truly homogeneous, truly cohesive body at its center. We have already discussed how part of this is not true – there were real wealth differences between spartiates from the beginning – but now I want to get in deeper into why that matters.

Because it turns out that – at least during the Classical Period (c. 480 to 323 B.C. – the period for which we have any really solid evidence for Spartan society) – even among the ‘free’ people of Sparta and even among the spartiates themselves, this commonality of life experience was a mirage. Life could look very different for the poor spartiate than the rich spartiate.

Before we dive in, I also want to remind you of a point we made in parts II and III, which is that the famed Spartan austerity is not nearly so old as our sources would have us believe. In many cases, scholars are placing it’s start closer to 500 B.C. than to 700 B.C. (much less c. 820 and Lycurgus), but the absolute best case for the Spartan system we observe is that it started in the mid-600s with the completion of the conquest of Messenia. That matters a great deal for talking about the stability of this system, which we’ll get to at the end.

As always, if you like what you are reading here, please share it; if you really like it, you can support me on Patreon. And if you want updates whenever a new post appears, you can click below for email updates or follow me on twitter (@BretDevereaux) for updates as to new posts as well as my occasional ancient history, foreign policy or military history musings.

Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous

As we discussed then, in every period for which we have evidence, there is evidence for significant disparities of wealth in Sparta, both between the classes, and within the spartiate citizen class.

Now the question becomes: what does that look like?

One of the key institutions here is the syssition (plural: syssitia). The syssitia were the common Spartan messes (available only for the spartiates). The ideal (e.g. Xen. Lac. 5.1-7; Plut. Lyc. 12) was that each member contributed a certain minimum amount to the communal mess group of around 15 people, the idea being that everyone in the group would have an equal portion of what the group brought. Crucially, membership in a syssition was a requirement for full citizenship (Plut. Lyc. 12.5-6) – a graduate of the agoge who nevertheless found themselves welcomed into no syssition did not become a full Spartiate (we’ll talk about what happens to them in a minute).

Let’s deal with the rich spartiate first.

And first, we need to note – picking up with last time – that assessing this question is difficult. As we saw last week, economic inequality among the spartiates was not new at any point we can see. But the nature of all of our sources – Plutarch, Xenophon, etc – is that they are almost always more interested in describing the ideal Spartan polity than the one that actually existed. And I want to emphasize – as we discussed the week before last – that this ideal policy does not seem to ever have existed, with one author after another placing that ideal Sparta in the time period of the next author, who in turn informs us that, no, the ideal was even further back.

It is important to begin by noting that the sheer quantity of food the spartiates were to receive from their kleros would make almost any spartiate wealthy by the standards of most Greek poleis – spartiates, after all, lived a live of leisure (Plut. Lyc. 24.2) supported by the labor of slaves (Plut. Lyc. 24.3), where the closest they got to actual productive work was essentially sport hunting (Xen. Lac. 4.7). If the diet of the syssition was not necessarily extravagant, it was also hardly…well, Spartan – every meal seems to have included meat or at least meat-broth (Plut. Lyc. 12.2; Xen. Lac. 5.3), which would have been a fine luxury for most poorer Greeks. So when we are talking about disparities among the spartiates, we really mean disparities between the super-rich and the merely affluent. As we’ll see, even among the spartiates, these distinctions were made to matter sharply and with systematic callousness.

Now, our sources do insist that the Spartan system offered the Spartiates little opportunity for the accumulation or spending of wealth, except – as noted last week – they also say this about a system they admit no longer functions…and then subsequently describe the behavior of wealthy Spartans in their own day. We’ve already noted Herodotus reporting long-standing wealthy elite spartiates as early as 480 (Hdt. 7.134), so it’s no use arguing they didn’t exist. Which raises the question: what does a rich Spartiate spend their wealth on?

In some ways, much the same as other Greek aristocrats. They might spend it on food: Xenophon notes that rich spartiates in his own day embellished the meals of their syssitia by substituting nice wheat bread in place of the more common (and less tasty) barley bread, as well as contributing more meat and such from hunting (Xen. Lac. 5.3). While the syssitia ought to even this effect out, in practice it seems like rich spartiates sought out the company of other rich spartiates (that certainly seems to be the marriage pattern, note Plut. Lys. 30.5, Agis. 5.1-4). Some spartiates, Xenophon notes, hoarded gold and silver (Xen Lac. 14.3; cf. Plut. Lyc. 30.1 where this is supposedly illegal – perhaps only for the insufficiently politically connected?). Rich spartiates might also travel and even live abroad in luxury (Xen. Lac. 14.4; Cf. Plut. Lyc. 27.3).

Wealthy spartiates also seemed to love their horses (Xen. Ages. 9.6). They competed frequently in the Olympic games, especially in chariot-racing. I should note just how expensive such an effort was. Competing in the Olympics at all was the preserve of the wealthy in Greece, because building up physical fitness required a lot of calories and a lot of protein in a society where meat was quite expensive. But to then add raising horses to the list – that is very expensive indeed (note also spartiate cavalry, Plut. Lyc. 23.1-2). Sparta’s most distinguished Olympic sport was also by far the most expensive one: the four-horse chariot race.

In other ways, however, the spartiates were quite unlike other Greek aristocrats. They do not seem to have patronized artists and craftsmen. The various craft-arts – decorative metalworking, sculpture, etc – largely fade away in Sparta starting around 550 B.C. – it may be that this transition is the correct date for the true beginning of not only ‘Spartan austerity’ but also the Spartan system as we know it. There are a few exceptions – Cartledge (1979) notes black-painted Laconian finewares persist into the fifth century. Nevertheless, the late date for the archaeological indicators of Spartan austerity is striking, as it suggests that the society the spartiates of the early 300s believed to have dated back to Lycurgus in the 820s may well only have dated back to the 550s.

The other thing we see far less of in Sparta is euergitism – the patronage of the polis itself by wealthy families as a way of burnishing their standing in society. While there are notable exceptions (note Pritchard, Public Spending and Democracy in Classical Athens (2015) on the interaction and scale of tribute, taxes and euergitism at Athens), most of the grand buildings and public artwork in Greek cities was either built or maintained by private citizens, either as voluntary acts of public beneficence (euergitism – literally “doing good”) or as obligations set on the wealthy (called liturgies). Sparta had almost none of this public building in the Classical period – Thucydides’ observation that an observer looking only at the foundation of Sparta’s temples and public buildings would be hard-pressed to say the place was anything special is quite accurate (Thuc. 1.10.2). There are a handful of exceptions – the Persian stoa, a few statue groups, some hero reliefs, but far, far less than other Greek cities. In short, while other Greek elites felt the need – or were compelled – to contribute some of their wealth back to the community, the spartiates did not.

Passing judgment on those priorities, to a degree, comes down to taste. It is easy to cast the public building and patronage of the arts that most Greek elites engaged in as crass self-aggrandizement, wasting their money on burnishing their own image, rather than actually helping anyone except by accident. And there is truth to that idea – the Greek imagination has little space for what we today would call a philanthropist. On the other hand – as we’ll see – a handful of spartiates will come to possess a far greater proportion of the wealth and productive capacity of their society. Those wealthy spartiates will do even less to improve the lives of anyone – even their fellow spartiates. Moreover, following the beginning of Spartan austerity in the 550s, Sparta will produce no great artwork, no advances in architecture, no great works of literature – nothing to push the bounds of human achievement, to raise the human spirit.

Also, I cannot, for the life of me, understand what all those leather straps are supposed to be – and I suspect that no suggestion I make will be sufficiently ‘PG’ for this setting!

I am not enamored of the idea that a system of oppression is ‘worth it’ because of the artwork its elite produces, if for no other reason that relatively more open, less oppressive societies generally produce more and better works. But if you must have systems of oppression and privilege – and no society of humans has yet learned to live completely without them – surely we may prefer the one that occasionally throws off things of value. Even if by accident.

This, Sparta does not do.

Rich Spartiate, Poor Spartiate

Ok, but how do wealthy spartiates happen? After all, each spartiate is supposed to only have one kleros – the standard plot of land with helots to support the household – right? While that might be the ideal, it’s not clear that the system ever worked that way. First and foremost, no two fields are the same – it is fundamentally certain that some kleroi were generally better than others, because of the variability of agriculture. Modern land-surveying is not up to the task of evenly dividing up agricultural productivity on the sort of multi-century time-scale that Sparta was looking at; ancient surveying was surely no better.

The other from-the-beginning factor are the two hereditary royal lines. The kings possessed large estates taken from the land of the perioikoi. Xenophon explicitly places this as part of the Lycurgean constitution (Xen. Lac. 15.3); we may dispense with Lycurgus but still assume that these estates represented holdings of long-standing. By the time we have any good sense of the wealth the kings can dispose of, it is considerable (e.g. Plut. Agis 9.3). The presence of two out-sized fortunes may not seem like a problem in this system, until you remember how tiny the spartiate elite is. Rather than being a rounding error, the friends and close family of the kings could easily form an elite within an elite – a point we will discuss in more depth next week.

Historically speaking, the two Spartan kings had a wide range of privileges, including large estates carved out of the land of the perioikoi. Also, this marching order is wrong – the skiritai – a specific sort of perioikoi – seem to have always made up the vanguard of the Spartan army prior to 370 (Xen. Lac. 12.3; Diod. 15.31.1; Xen Hell. 5.2.24) , followed by the king – of course they can’t do that here, because they’ve removed the only Spartan scouts, since they were non-citizens.

These pre-existing wealth inequalities seem to have been greatly intensified in the fifth century by two things: Spartan inheritance patterns and the great earthquake of 464.

At some point, it became possible – or perhaps always was possible – for kleroi to be inherited. Plutarch attributes this (Plut. Agis. 5.1-3) to a certain Epitadeus in a just-so story that, so far as I can tell, functionally no modern scholars believe. Instead, they are divided between those who think kleroi was effectively always inheritable and those who think that there is some break with this trend (notably Figueira), although probably coming before the fourth century – it presumably would have to have happened close to 500 B.C. given how rapidly its pernicious impacts take effect. In any case it seems to have been possible during the fourth century – and probably most of the fifth – for spartiates to bequeath their kleroi to whomsoever they wished.

(Dating note: I want readers to note here – because we’ll come back to it – how chronologically tight the ‘ideal’ Sparta is getting. The main of the constitution in place no earlier than 680, Spartan austerity and thus the Spartan ‘ideal’ no earlier than 550, and the seeds of the irretrievable collapse no later than 500, the golden age of Sparta is beginning to look quite short indeed!)

One effect of this method of inheritance, it seems, is that it became possible for property to move through – and be controlled by – spartiate women (Arist. Politics 2.9, Plut. Agis 7.3-4). We do not need to share our male sources disgust at this state of affairs (Plutarch is more measured, but Aristotle is openly contemptuous of it), there is obviously nothing wrong with female landholding. The problem, as we’ll see, is that the Spartan system’s inflexibility is completely incapable of dealing with the problems this creates when combined with the syssitia. Nevertheless, over time it seems that the role of spartiate women in controlling the wealth of the economy increased. On the one hand, this may seem positive, but remember the nature of wealth in Sparta – this just means that spartiate women increasingly ‘got in’ on the spartiate helot-exploitation racket. One assumes being brutally exploited by women is no better than being brutally exploited by men.

If we strip away Aristotle’s misogyny (and again, we should), we can see that this problem exists even if women cannot inherit. After all, a spartiate with no children (or only daughters) might still opt to bequeath his property – including his kleros – to a friend or a political ally. A spartiate with multiple male heirs might see his kleros divided – or else watch his younger sons (or less favored sons) fall into poverty. We might still see political marriages steadily concentrating wealth and connections among a shrinking elite arrayed around the kings with their large ancestral estates. As we’ll see next time, the elite of the spartiates – the elite within the elite – do not seem to have shied away from using their own political connections to accelerate the concentration of wealth at the top, to the utter ruin of the Spartan state.

(If I may for a moment, note a comparison: Roman women could own land and write wills from a very early point, and while Roman conservatives (e.g. Juvenal) find this frustrating, Rome got along just fine. Indeed, while Rome was still a deeply misogynist society by modern standards, it is quite evident that Roman women were in a better legal position compared to any Greek city, including Sparta. So, to reiterate, the problem is not that Spartan women can inherit, the problem is the closed and rigid nature of the spartiates themselves.)

We also need to remember that this is not the origin of economic inequality among the spartiates, merely a fact of law – that kleroi are inherited, rather than passing into some collective redistribution on death – which gives the already-rich a tool to continue concentrating their wealth. Now, in other poleis, this tendency might be offset by the emergence of fortunes outside of landholding – a potter or tanner ‘makes good’ and buys some farmland (perhaps from an ailing aristocrat) creating a new landholding household. Alternately, poleis had liturgies and euergitism to funnel some of that wealth back into the community. Sparta has none of this. While land can be inherited, it cannot be bought and even if it could, the only fellows who can own the good farmland – the kleroi cover almost all of the good farmland – are forbidden from taking up any productive work anyway. Rich spartiates were better positioned to arrange advantageous marriages and inheritances for themselves (Plut. Lys. 30.5, Agis. 5.1-4). Wealth was thus left to compound itself in a zero-sum environment where new ‘start-ups’ are legally prohibited.

Such a system is already unstable, which bring us to the second factor: the great earthquake of 464.

The earthquake of 464 had two effects to this system, as near as we can tell, both of them bad. In essence, it boils down to a fairly grim summary: the earthquake killed a lot of spartiates and a lot of helots, and it probably did both unevenly. On the spartiate end, the earthquake, by destroying entire households probably accelerated the concentration of kleroi, both by triggering a bunch of inheritance all at once and also by removing entire households while leaving others untouched. As entire households fizzled out, their kleroi would have been funneled – via the inheritance issues noted above – to some of the remaining households, reducing the total number of independant kleroi even while the amount of kleruchal land remained the same.

The impact to and of (because, remember the helots are people who make their own decisions!) the helots is more complex. Because the death toll of the disaster was likely geographically uneven, some kleros-holders would find their labor forces essentially untouched, while other helot households would be wiped out. As we discussed last time, the nature of mortality among peasant communities means that they might ‘bounce back’ demographically in just a few generations, but in the short-term, a spartiate whose kleros‘ helots had been decimated could be thrust very suddenly into bad economic straits, as his land no longer produced enough return to meet the demands of the syssitia.

Finally, the helots of Messenia revolted – presumably taking advantage of the damage to Sparta – setting up their stronghold on Mt. Ithome, the traditional site of Messenian resistance. Alas, the Messenians eventually lose, although there is a period of significant disruption of the kleroi in Messenia for several years during the revolt and a significant proportion of the Messenians find refuge eventually in Athens, further disrupting Sparta’s labor supply (Thuc. 1.101ff). That means that some spartiates will have seen their labor force – enslaved helots – killed in the quake, others killed in the revolt, others escaped to Athens. As we’ll see, given the tight structure of Spartan institutions, such an economic disruption could mean disaster.

What seems to have happened then is that the spartiate citizen body shrunk, but rather than being able to bounce back, the freed up kleroi were absorbed into the estates of other spartiates, either via direct bequest, or by matrilineal inheritance. Since the kleros and its agricultural production were required – via the syssitia contribution – for new spartiates to enter the system, the decline was ‘locked in.’ At the same time, spartiates whose helots were either dead or in revolt suddenly found themselves poor. Which brings us to:

Falling off the Ladder

What are affairs like for poor spartiates?

First, we need to reiterate that a ‘poor’ spartiate was still quite well off compared to the average citizen in many Greek poleis – we talk about ‘poor’ spartiates the same way we talk about the ‘poor’ gentry in a Jane Austen novel. None of them are actually poor in an absolute sense, they are only poor in the sense that they are the poorest of the rich, clinging to the bottom rung of the upper class.

Nevertheless, we should talk about them, because the consequences of falling off of that bottom rung of the economic ladder in Sparta were extremely severe because of the closed nature of the spartiate system. Here is the rub: membership in a syssition was a requirement of spartiate status, so failure to be a member in a syssition – either because of failure in the agoge or because a spartiate could no longer keep up the required mess contributions – that meant not being a spartiate anymore.

The term we have for ex-spartiates as hypomeiones (literally “the inferiors”), which seems to have been an informal term covering a range of individuals who were (or whose family were) spartiates, but had ceased to be so. The hypomeiones were, by all accounts, mostly despised by the spartiates and the hatred seems to have been mutual (Xen. Hell. 3.3.6). Interestingly in that passage there – Xenophon’s Hellenica 3.3.6 – he lists the Spartan underclasses in what appears to be rising order of status – first the helots (at the bottom), then the neodamodes (freed helots, once step up), then the hypomeiones, and then finally the perioikoi. The implication is that falling off of the bottom of the spartiate class due to cowardice, failure – or just poverty – meant falling below the largest group of free non-citizens, the perioikoi.

Herodotus gives some sense of the treatment of men who failed at being spartiates when he details the two survivors of Thermopylae – Aristodemus and Pantites. Both had been absent from the battle under orders – Pantites had been sent carrying a message and Aristodemus had suffered an infection. When they returned to Sparta, both were ostracized by the spartiates for failing to have died – Pantites hanged himself (Hdt. 7.232) while Aristodemus was held to have ‘redeemed’ himself with a suicidal charge at Plataea which cost his life (Hdt. 7.231). And as a side note: Aristodemus is the model for 300‘s narrator, Dilios – so when you see him in the movie, remember: the spartan system drove these men to pointless suicide because he followed an order.

But my main point here is that falling out of the spartiate system meant social death. Remember that the spartiates are a closed class – failing at being a spartiate because your kleros is too poor to maintain the mess contribution means losing citizen status; it means your children cannot attend the agoge or become spartiates themselves. It means you, your wife, your entire family forever are shamed, their status as full members of society forever revoked and your social orbit collapses on you, since you are cut off from the very ties that bind you to your friends. No wonder Pantites preferred to hang himself.

In essence then, the core of the problem here is not that these poor spartiates were poor in any absolute sense – they weren’t. It was that the difference between being rich and being merely affluent in Sparta was a social abyss completely unlike any other Greek state. And that abyss was completely one way. As we’ll see – there was no way back.

Our sources are, unfortunately, profoundly uninterested in answering some crucial questions about the hypomeiones: did they keep their kleroi? What happened to the status of their children? What happened to the status of the women in their families? We can say one thing: it is clear that there was no ‘on-ramp’ for hypomeiones to get back into the spartiate system. This is made quite clear, if by nothing else, by the collapsing number of spartiates (we’ll get to it), but also at the inability of extremely successful non-Spartan citizens – men like Gylippus and Lysander – to ever join the homoioi. Once a spartiate was a hypomeiones, they appear to have been so forever – along with any descendants they may have had. Once out, out for good.

All of that loops back to the impact of the great earthquake in 464. It is likely there were always spartiates who – because their kleroi were just a bit poorer, or were hit a bit harder by helot resistance, or for whatever reason – clung to the bottom of the spartiate system financially, struggling to make the contributions to the common mess. When the earthquake hit, the death of so many helots – on whom they relied for their economic basis – combined with the overall disruption seems to have pushed many of these men beyond the point where they could sustain themselves. Unlike in a normal Greek polis, they could not just take up some productive work to survive and continue as citizens, because that was forbidden to the spartiates, so they collapsed out of the class entirely.

(As an aside – the fact that wealthy spartiates, as mentioned, seemed to prefer each other’s company over the rest probably also meant that the social safety-net of the poor spartiates likely consisted of other poor spartiates. Perhaps in normal circumstances they remained stable by relying on each other (you help me in my bad year, I help you in yours – this is very common survival behavior in subsistence agriculture societies), but the earthquake – by hitting them all at once – may well have caused a downward spiral, as each spartiate who fell out of the system made the remainder more vulnerable, culminating in entire social groups falling out.)

As I said, our sources are uninterested in poor spartiates, so we can only imagine what it must have felt like, clinging desperately to the bottom of that social system, knowing how deep the hole was beneath you. One imagines the mounting despair of the spartiate wife whose job it is to manage the household trying to scrounge up the mess contributions out of an ever-shrinking pool of labor and produce, the increasing despair of her husband who because of the laws cannot do anything but watch as his household slides into oblivion. We cannot know for certain, but it certainly doesn’t seem like a particularly happy existence.

As for those who did fall out of the system we do not need to imagine because Xenophon – in a rare moment of candor – leaves us in no doubt what they felt. He puts it this way: “they [the leaders of a conspiracy against the spartiates] knew the secret of all of the others – the helots, the neodamodes, the hypomeiones, the perioikoi – for whenever mention was made of the spartiates among these men, not one of them could hide that he would gladly eat them raw” (Xen. Hell. 3.3.6; emphasis mine).

The Underclass and the Army

One thing that is very clear from the figures we have in our sources is that as the size of the spartiate citizen body decreased, the Spartan military system became increasingly reliant on the participation of members of its underclasses. This was not new: the better-off perioikoi had apparently always fought as hoplites alongside (and under the command of) the spartiates. Likewise, the new classes of freed helots – the Brasideioi and Neodamodeis – were drawn into the hoplite phalanx, fighting alongside the spartiates just as the perioikoi did.

The role of the two other non-citizen free underclasses, the hypomeiones and the mothakes is more interesting. As we noted before, the hypomeiones seem to have been chiefly the men who came from households that had fallen off the bottom of the spartiate system, while the mothakes were the children of spartiate fathers and helot mothers. These men, it seems, could be sponsored through the agoge by friendly spartiates and thus not only become part of the Spartan army like the perioikoi, but – quite unlike the perioikoi – rise through the ranks to positions of importance (but, to be clear, they could not become spartiates, even if they succeeded in the agoge).

In 300, he is the only member of any of Sparta’s non-citizen free underclasses we see (despite there having been c. 900 perioikoi at the actual battle), since he would presumably classify as a hypomeion.

Don’t worry Movie!Ephialtes – the Spartans will refuse to let far better folks than you into their club, to their eventual complete ruin.

We have only a few examples of men like this, all from a fairly short time period from around 415 to around 395. The key figures are two mothakes, Lysander and Gylippus, and one hypomeion, Cinadon. I should note none of our sources stops point-blank and says that these men are in these classes, but the situation of their early life allows us to infer with quite a bit of confidence. They are all clearly not spartiates.

Their three careers – which all happen within around 20 years of each other – actually follow a similar trajectory: all three achieve remarkable military success in something other than straight-up hoplite battle – the command of those armies seems to have remained mostly the purview of the kings and other important spartiates. All three rose to prominence, and were then eventually marginalized (and in two of the cases, destroyed) by political opposition in Sparta, from the spartiates. None of the three managed to actually break back into the spartiate class, despite in some cases truly incredible achievements.

The most notable of the bunch is the admiral, Lysander. Lysander was the architect of Sparta’s defeat of Athens, winning major naval victories at Notium (406) and Aegospotami (405) which forced the capitulation of Athens and ended the Peloponnesian War. Lysander was prominent for a time, among other things arranging the selection of Agesilaus II to succeed Agis II as one of the two hereditary Spartan kings (Plut. Lys. 22), but was almost immediately sidelined by Agesilaus, sent to a do-nothing command at the Hellespont (Plut. Lys. 24.1-2). Lysander was returned to a meaningful command – of hoplites no less – with the outbreak of war with Corinth and was killed in the first major action (Haliartus – 395). After his death his memory was badly tarnished by the revelation of a plot he had been brewing to effect political change in Sparta (Plut. Lys. 30.3), which – I tend to agree with Kennell – seems in keeping with his character.

Lysander was – without a doubt – the most successful of these men, but as I noted, the others follow the same basic trajectory. Gylippus was sent as a military advisor to Syracuse to help it defend itself against an Athenian invasion in 414 (this is the famous and ill-fated Sicilian Expedition). Gylippus accomplishes his task with stunning effectiveness, but was accused – our sources believe rightly – of embezzling some of the spoils of the victory at Aegospotami and fled into exile rather than face execution (Diodorus 13.106.7-10).

Cinadon, the last and least notable of the bunch, was evidently skilled enough for it to be normal for him to have command of small units of the cavalry (Xen. Hell. 3.3.9-10) and to be entrusted with secret coded dispatches. That clearly suggests some military ability and Xenophon actually describes Cinadon as being strong in both body and courage. Cinadon himself had begun plotting to effect political change such that he might “be inferior to no one in Lacedaemonia” (that is, to become one of the homoioi), was subsequently discovered, arrested and executed by the ephors, along with his compatriots (Xen. Hell. 3.3.11).

These three figures – particularly Lysander – are occasionally pointed to as examples of the potential for mobility for at least some of the Spartan underclasses. I think this reading cannot really be sustained. First, this does not signal any permanent change in the Spartan system – the age of the upwardly mobile non-spartiate commander opens and shuts within a single generation, prompted, it seems, by severe need in the late stages of the Peloponnesian War. We can’t know, but I strongly suspect, that Cinadon’s abortive coup might have been the result of ambitious mothakes and hypomeiones in the 390s realizing that – with the fall of Lysander – they would never be good enough to join the spartiates. Moreover, and this is crucial: none of these men that we know of – not even Lysander, who defeated Athens – seems to have actually broken into the spartiate class from below.

Conclusions: Oliganthropia

The consequence of the Spartan system – the mess contributions, the inheritance, the diminishing number of kleroi in circulation and the apparently rising numbers of mothakes and hypomeiones – was catastrophic, and once the downhill spiral started, it picked up speed very fast. From the ideal of 8,000 male spartiates in 480, the number fell to 3,500 by 418 (Thuc. 5.68) – there would be no recovery from the great earthquake. The drop continued to just 2,500 in 394 (Xen. Hell. 4.2.16). Cinadon – the leader of the above quoted conspiracy against the spartiates – supposedly brought a man to the market square in the center of the village of Sparta and asked him to count – out of a crowd of 4,000! – the number of spartiates, probably c. 390. The man counted the kings, the gerontes and ephors (that’s around 35 men) and 40 more homoioi besides (Xen. Hell. 3.3.5). The decline continued – just 1,500 in 371 (Xen. Hell. 6.1.1; 4.15.17) and finally just around 700 with only 100 families with full citizen status and a kleros, according to Plutarch by 254 B.C. (Plut. Agis. 5.4).

This is is the problem of oliganthropia (‘people-shortage’ – literally ‘too-few-people-ness’) in Sparta: the decline of the spartiate population. This is a huge and contentious area of scholarship – no surprise, since it directly concerns the decline of one of the more powerful states in Classical Greece – with a fair bit of debate to it (there’s a decent rundown by Figueira of the demography behind it available online here). What I want to note here is that a phrase like ‘oliganthropia’ makes it sound like there was an absolute decline in population, but the evidence argues against that. At two junctures in the third century, under Agis IV and then later Cleomenes III (so around 241 and 227) attempts were made to revive Sparta by pulling thousands of members of the underclass back up into the spartiates (the first effort fails and the second effort was around a century too late to matter). That, of course, means that there were thousands of individuals – presumably mostly hypomeiones, but perhaps some mothakes or perioikoi – around to be so considered.

Xenophon says as much with Cinadon’s observation about the market at Sparta. Now obviously, we can’t take that statement as a demographic survey, but as a general sense, 40 homoioi, plus a handful of higher figures, in a crowd of 4,000 speaks volumes about the growth of Sparta’s underclass. And that is in Laconia, the region of the Spartan state (in contrast to Messenia, the other half of Sparta’s territory), where the Spartans live and where the density of helots is lowest.

This isn’t a decline in the population of Sparta, merely a decline in the population of spartiates – the tiny, closed class of citizen-elites at the top.

So we come back to the standard assertion about Sparta: its system lasted a long time, maintaining very high cohesion – at least among the citizens class and its descendants. This is a terribly low bar – a society cohesive only among its tiny aristocracy. And yet, as low of a bar as this is, Sparta still manages to slink below it. Economic cohesion was a mirage created by the exclusion of any individual who fell below it. Sparta maintained the illusion of cohesion by systematically removing anyone who was not wealthy from the citizen body.

If we really want to gauge this society’s cohesion, we ought to track households, one generation after the next, regardless of changes in status. If we do that, what do we find? A society with an increasingly tiny elite – and a majority which, I will again quote Xenophon, would eat them raw. Hardly a model of social cohesion.

Moreover, this system wasn’t that stable The core labor force – the enslaved helots – are brutally subjugated by Sparta no earlier than 680 (even this is overly generous – the consolidation process in Messenia seems to have continued into the 500s). The austerity which supposedly underlined cohesion among the spartiates by banishing overt displays of wealth is only visible archaeologically beginning in 550, which may mark the real beginning of the Spartan system as a complete unit with all of its parts functioning. And by 464 – scarcely a century later – terminal and irreversible decline had set in. Spartan power at last breaks permanently and irretrievably in 371 when Messenia is lost to them (we’ll talk about it, don’t worry).

This is a system that at the most generous possible reading, lasted three centuries. In practice, we are probably better in saying it lasts just 170 or so – from c. 550 (the completion of the consolidation of Messenia, and the beginning of both the Peloponnesian League and the famed Spartan austerity) to 371.

To modern ears, 170 years still sounds impressive. Compared to the remarkably unstable internal politics of Greek poleis, it probably seemed so. But we are not ancient Greeks – we have a wider frame of reference. The Roman Republic ticked on, making one compromise after another, for four centuries (509 to 133; Roman enthusiasts will note that I have cut that ending date quite early) before it even began its spiral into violence. Carthage’s republic was about as long lived as Rome. We might date constitutional monarchy in Britain as beginning in 1688 or perhaps 1721 – that system has managed around 300 years.

While we’re here – although it was interrupted briefly, the bracket dates for the notoriously unstable Athenian democracy, usually dated from the Cleisthenic reforms 508/7 to the suppresion of the fourth-century democracy in 322, are actually longer, 185 years, give or take, with just two major breaks, consisting of just four months and one year. Sparta had more years with major, active helot revolts controlling significant territory than Athens had oligarchic coups. And yet Athens – rightly, I’d argue – has a reputation for chronic instability, while Sparta has a reputation for placid regularity. Might I suggest that stable regmines do not suffer repeated, existential slave revolts?

In short, the Spartan social system ought not be described as cohesive, and while it was relatively stable by Greek standards (not a high bar!) it is hardly exceptionally stable and certainly not uniquely so. So much for cohesion and stability.

Next week, it’s eunomia (lit: ‘good laws’ but more generally being ‘well ruled’) that’s on the chopping block: we’re going to look at the government of Sparta. The catastrophic decline of the spartiates was – after all – obvious even at the time. Why wasn’t the Spartan state able to adapt to this challenge? Why did the first real attempt to address it only come in 254 B.C. – more than a century after it had broken Spartan power – and why did even that attempt fail?

Couple typos: “one last time” twice in the same sentence, and “interchangeably” for interchangeable. “lasts just 170 or so” should probably include “years,” as written the closest antecedent is “centuries” which clearly isn’t right. “stable regmines”.

Something no one ever brings up. The real reason for the fall of Sparta is their Women. They only had one job to do, have kids, and didn’t do it. Since they had better food and health than the rest of the population they could have easily had enough children to raise the population substantially. Look at the population increases of Women in the early US as an example. The reason Sparta fell is they ran out of Spartans. All the gnashing of teeth about how hard it was to get into or stay in the citizen class would have amounted to nothing if the Spartan Women had just had some kids.

No, I think not.

You are treating Spartan oliganthropia as a purely demographic issue when scholars have known (and said) for decades and decades that it wasn’t. The problem is not the lack of children (as the growing ranks of the hypomeiones and mothakes attest to – plenty of kids) but the steady consolidation of kleroi. A Spartan woman can have as many children as she likes, but if she has only the one kleros, then only one of those children will have the economic support to be a Spartiate. That process can function exactly the same way at any proposed birthrate.

The birth rate is quite beside the point. That said, while our sources tell us that Spartiate women strongly valued children (and thus endeavored to have many), the Spartan lifestyle system was calibrated to reduce birthrates (by, for instance, limiting conjugal contact among prime-age couples, Plut. 15.4-5). It is profoundly unreasonable to fault Spartiate women for failing to have children when she and her husband have to engage in subterfuge in order to conceive any. And, I feel the need to note, those were laws made and enforced by Spartiate *men.*

Finally, it is extremely anachronistic to assume that Spartiate women had any great degree of control in their own reproduction. Sparta was still a patriarchal state, and effective birth control for Spartiate women would have been practically non-existent (wealthy Greeks might have had access to imported silphium from Cyrene, which may have been an effective contraceptive – it is now extinct, so we’ll never know – but Sparta, with its disdain for trade can hardly have imported it in any real amount). Moreover, the Spartan marriage ritual (Plut. 15.3) is unreconstructed abduction; it is fanciful to assume that many Spartiate women felt empowered (at least on a social/legal level, not on a personal one) to refuse their husbands. Again: the blame must accrue to the fellows with all of the power: spartiate men.

So ‘no one ever brings this up’ because it doesn’t speak to the actual phenomenon in question, doesn’t really consider the ancient evidence, introduces anachronistic assumptions, and fails to take into account the actual power structure in this society. They didn’t bring it up because it isn’t a very good idea.

I’m still confused on this point.

If kleroi are being consolidated, that sounds like it means that a bunch of spartiate households have two (or more) of them. If a household has two kleroi and two sons, could each son inherit one kleros, thereby bumping the number of male spartiates back up?

Because Sparta was a society apparently engineered for a relatively low birth-rate, mostly by separating men from their wives during their peak childbearing years and – if one buys our sources on this point – through extensive male infanticide.

So while it is entirely possible that kleroi occasionally got split back up again, as best we can tell it seems to have more frequently been the case that households had 1 or 0 sons than that they had 2+; consequently the rate of household consolidation outpaced the rate at which kleroi were divided.

Which is actually not shocking – we see similar effects in the aggregate population among the English early modern gentry, who seem quite clearly to have fewer children than fertility math would suggest. Clearly there was an effort, once the one or two sons were achieved to restrain the (legitimate) birth-rate. Of course reliable, high-effectiveness birth control was not really available, but even unreliable, low-effectiveness methods can have significant overall impact in the aggregate. I’ve seen suggestions that ‘fertility awareness’ methods have a failure rate around 25% – but that means they have a *success* rate of around 75%…and if a large portion of your landholding families are attempting to avoid splitting the estate up, even a modest effectiveness rate is going to mean many of them succeed when you are looking at a large aggregate population.

Interesting. I’d been picturing some sort of inflationary effect–once lots of spartiates have two kleroi, all the good syssitia double their dues, so now all the spartiates think they need two kleroi–but I guess that would be more about why people try to have fewer children rather than how, in practice, they would come to have fewer children.

According to Wikipedia, calendar-based fertility methods didn’t work until about the early twentieth century because a lot of physicians thought that the wrong part of the cycle was the fertile time. That 75% effectiveness rate I’ve seen mentioned as including people who take their temperature every morning and people who check their cervical fluid every day (and people who do both)–the first isn’t available until the development of high quality oral thermometers, and the second doesn’t seem to have been understood until the mid-twentieth century. (Both methods are much better at preventing pregnancy than anything calendar-based.) So I suspect that depressed birth rates (in either Sparta or English gentry) has more to do with spouses sleeping separately than fertility awareness.

Don’t forget genetic issues. With a small number of elite and no pathway to joining the elite and probably the desire to reconstitute kleroi split due to multiple heirs, there probably would have been cousin marriage. Like the Hapsburgs. PS just found out about this blog. Great reading!

Ah yes, the Molyneux argument* for Sparta. Put the blame on women for their reproductive habits, regardless of how much power the women have in that decision and whether changing reproductive habits would actually change anything meaningful.

*To nearly quote, that all the world’s problems come from women having children with jerks.

I note that blaming women for childbearing ‘habits’ they have no meaningful control over has been a common tactic of patriarchs with a problem for generations. See also the countless women who have been treated as somehow lesser-than, or even divorcible, on the grounds that they’ve borne daughters but no sons.

Because OF COURSE women can control that.

[rolls eyes]

Now, that’s pretty much the maximum silliness of the habit, but it’s certainly a recurring pattern otherwise. A man tells women, either present or historical, that their job is to turn out babies (or babies that meet a certain set of “quality assurance” standards) and that if the babies do not materialize, it’s their fault.

It takes two to tango!

So, ah, how are these women avoiding having children? In Ancient Greece? When childbearing is literally their only job?

Hmm. Now the population of Sparta actually is pretty solid. There sure are a lot of the helot/spartan underclass kids, enough that they have their own class.

One wonders what kind of sexual response a man who goes through the spartan youth system has, where the only intimacy might be repeated sexual violence by the guys who you train with, fight with, and lets not forget, thrill kill slaves with. As well as rape whoever they get their hands on. A system based on violence and degradation.

Probably can’t treat full citizens the same way, right? Also, probably they don’t get Casanova classes in Sparta.

Women can’t have kids on their own. Do they have willing partners? Are they receptive to the kind of um ‘lovin’ that Spartan men grow up dishing out? Because to the Spartans, their memory of young love has to be pretty different than ours. Hopefully.

More to the point, they practice infanticide, as well as lose a bunch in the school system, and let’s not forget that they are in their 30’s before they have opportunity.

But, sure, maybe it’s all the women’s fault. Somehow. Pfft.

Also, in plutarch’s lives,it is mentioned bachelors are often shamed if they did not conceive with a women yet. Young girls from rich spartiate families are often wedded off to spartiate men (old and young) Older spartiates can introduce their wives to younger men (whether the women wish to or not) who they feel would produce strong offspring for them and adopt the child. It is even compared that women are like ‘bitches and mares’ that they can breed with the strongest male. Lycargus praised women who died of childbirth and centered women’s education ad upbringig to believing strong bodies can produce strong offsprings and women should be proud of strong newborns. Plutarch made laws that encourage spartiate men to reproduce with women. And let’s be real, even if the women didn’t want to, they were forced to have intercourse. The fall of spartiates cannot be blamed on whether women felt like having sex because they have no say in that matter, or marriage, like many women of ancient times (and even now) who are treated very unequally.

Thank you for that in-detail look at Sparta.

It’s interesting to see the economic inequality in details, but also how a military system that doesn’t attempt to have meritocracy, but rather “being friends with the king, or his friends (Influential people) leads to advancement.

Some of this was hinted at in the first article, when you explained the system for the child soldiers; if there is no military training, then there is no objective measurement to advance the best pupils to officer ranks.

Likewise, even if each family has only one kleroi, they’re still not equal in terms of how much they bear and how many people must be fed from it.

Huh. Beginning proofreading corrections right with the introductory paragraph this time:

meager benefits were afford to elite -> meager benefits were afforded to elite

are identical and interchangeably. -> are identical and interchangeable.

are placing it’s start closer -> are placing its start closer

that this ideal policy does not -> that this ideal polity does not

supposed to only have one kleros -> supposed to have only one kleros (just to be pedantic about it :))

had two effects to this system -> had two effects on this system

men to pointless suicide because he followed -> men to pointless suicide because they

followed

about as long lived as Rome -> about as long-lived as Rome

Oops. Thought I had proofread my coding:

meager benefits were afford to elite -> meager benefits were afforded to elite

are identical and interchangeably. -> are identical and interchangeable.

Where to start?

First, everything written about the Spartans are written by their enemies or so far out of their actual existence as to be questionable at best (Looking at you, Plutarch.)

But let’s do Aristodemus and Pantites. According to BD, the military is a King’s friends millionaire’s club.

Second, these guys have literally had decades of facing existential threats together, because Spartans fought. A lot! There is this French phrase which says something about how this binds men.

Lastly, these Spartans at the time were facing an existential threat from the Persians. So they needed every man Jacque to be a meat shield, if not an actual accomplished fighting man. If they were willing to essentially devastate their artisan caste to die in the meat grinder of battle, how bad do you need to be to be cut from the Team at the last minute?

But, duh, they were evil and stupid! That has been the message for the last four posts. This is the difference between reading history and actually being in the military. We have this term: malingering. We know who is a POS (Person of Suspicion…) and someone who actually has your back because we live with them.

Here is Pantites’ story, and recall, with everyone else dead, there is absolutely no one to check with if he was actually given orders (but if he wasn’t given orders, then Spartans wouldn’t be evil and stupid, ergo…)

So, Pantites, ALONE, is going to go through the war lines of tens of thousands of Persians, up the coast owned by Persians, to a nation, who not only already gave earth and water to the Persians, but were OCCUPIED by the Persians, and their ruling class was ‘fighting’ (read hostages) for the Persians. This was supposedly King Leonidas’ big plan.

What is that smell? Anyone else smell BS?

Anyone have any questions for this guy? What was the message? Did the king give you any sigils to prove you were a messenger? Where are they? How long were you gone? Why were you gone that long? If we ask the Aleuadae, what is he going to say? Nothing because he was already a Persian tool? Well, we all knew Thessaly gave earth and water. Their ambassador TOLD us this when they visited.

Bear in mind, all the Thermopylae battle took place in three days. This Pantites AND the entire Thessaly military must have the shoes of Hermes to not only run up, but run back to actually have any effect on the battle. Did Leonidas think he could hold for a week? Did anyone else think that?

Of course, the current Spartans and mess mates already knew if Pantites was a guy the King would trust or a guy who was always late to the battle; something a bit harder for a Thucydides or a Plutarch to figure out. If they wanted to figure it out (I am guessing ‘no’ on that question).

Same with Aristodemus. “So, the king had a broken arm, a stabbed foot, and he stayed, but he said you could come back because you had a boo boo in your eye. And your friend went back anyway to die in glory. And who is alive to back up this story?”

Yeah.

Now, let’s talk about the syssitia (I did NOT think that word would pass spellcheck. Amazing).

There is a monthly contribution which was missing in the description. “Each member was required to contribute a monthly share to the common pot, the φιδίτης phidítes, of which the composition has been noted by Dicaearchus (through Athenaeus and Plutarch ibid., 12): 77 litres of barley, 39 litres of wine, three kilograms of cheese, 1.5 kilograms of figs, and ten Aegina obols, which served to purchase meat. That served to prepare the main dish, the black soup, of which Athenaeus noted the ingredients: pork, salt, vinegar and blood.” (Wiki)

So this onerous tax on these millionaires broke down to two bottles of wine a day, 100 grams of cheese, 50 grams of figs, and 2.5 liters of raw barley made into porridge or bread …essentially what a male in fighting condition would need to stay fed regardless of his status. Did anyone do the math on this?

So yes, Spartans were thrown out if they couldn’t essentially feed themselves. Kind of a low bar to competency.

But that is simply my opinion.

We can always lawyer-up a situation and we don’t know exactly what happened at the battle.

Leonidas was fighting a siege operation where he had to keep the wall and the persians had to get over or around the wall. The main challenges to siege operations are starvation (likely to afect the persians first), disease (both sides) and morale (likely to affect the greeks first, the Phocians ran away from their security duty). Leonidas might have thought that Aristodemus and Eurytus were a point of infection or a displeasure to the gods and he sent them away. Eurytus returned and was blind when he was killed. Aristodemus was accused of not doing the same suicide charge.

Pantites was sent aways before the contact of the armies. Leonidas plan was to hold Thermopilae and wait for the persians to fall back due to insuficient food and water. Thessaly might have offered inteligence, volunteers or a switch of alliance on the next phase of the campaign. It was not uncommon to test the intentions of enemy contigents/ states, especially if they had the same civilization. He could certainly move around the teritory with ease as he looked like a Greek and there were many Greeks in the Persian army anyway. The Thessalians had no reason to hand him over to the Persians as he was not a high ranking individual and it would have made the Persians suspicious.

>First, everything written about the Spartans are written by their enemies or so far out of their actual existence as to be questionable at best (Looking at you, Plutarch.)

The fact that the Spartans didn’t write anything down about *themselves* is not really a point in their favor… But that aside, while the things written about the Spartans may have been written by Athenians, they were written *with an approving tone.* Xenophon may not have been a Spartan himself, but he certainly didn’t disapprove of them, for instance.

===================

>But let’s do Aristodemus and Pantites… Lastly, these Spartans at the time were facing an existential threat from the Persians. So they needed every man Jacque to be a meat shield, if not an actual accomplished fighting man. If they were willing to essentially devastate their artisan caste to die in the meat grinder of battle, how bad do you need to be to be cut from the Team at the last minute? But, duh, they were evil and stupid! That has been the message for the last four posts. This is the difference between reading history and actually being in the military. We have this term: malingering. We know who is a POS (Person of Suspicion…) and someone who actually has your back because we live with them.

So your argument is that the Spartans, with hundreds of soldiers, needed every warm body so desperately that they couldn’t spare a single man as a scout or messenger, nor would they have? Or that these scouts and messengers chosen would be men with a reputation for unreliability and cowardice? I don’t buy it.

====================

>So yes, Spartans were thrown out if they couldn’t essentially feed themselves. Kind of a low bar to competency.

Remember that this isn’t a competency test! It isn’t a test of “feeding themselves!” Spartiates are expressly forbidden by law from “feeding themselves!” This is not a pass/fail test of an individual’s own economic output. It’s a “can you furnish food and money of acceptable quality as a surplus from the estate worked by your slaves?” This really does depend *entirely* on how productive the estate is, whether the spartiate’s slaves are alive or have run off or died in a revolt, and so on.

Agricultural surplus in this era was not consistent or large. In a normal society, this kind of aristocratic lordly proprietor could make up the difference in his estate’s productivity by personally laboring on his own farm. Spartiates could not do this… which in turn made it a lot easier for their estate to fail to provide the required contributions of food. At least until the individual estates got consolidated down to a small enough number of spartiates that *even in the worst years,* even the smallest estates were big enough to provide surplus food for one completely idle adult male to contribute to his mess.

What if they’re stable slave revolts?

Jokes aside, I’m glad we’ve moved beyond this kind of social system as a species. No longer do we have an economic system where a tiny minority holds most of the wealth, a minority which shrinks in size but grows in influence as some of them accumulate even more wealth (a process which accelerates under any economic hardship), with social mobility between classes being nonexistent.

Now, social mobility is only almost nonexistent.

People who think having to wear a mask during a pandemic or face limits on social mobility are equivalent to slavery or Stalinism or both or even worse. Stuck here in my air-conditioned house, a little overweight, unable to afford a beach house let alone a yacht with a helicopter, I’m functionally a helot! Let me go to the fridge and get a beer.

Okay, and what of those of us who lost our main sources of income during the pandemic (and those sources were hand-to-mouth to begin with) and are now counting every penny and having to choose between food and rent? On average, 12% of Americans struggle to maintain enough income to both house AND feed themselves, which sure, isn’t the same thing as being a helot, but there’s a certain… let’s say *essence* of experience between the two. Wondering how in the world you’ll get enough food to feed your children, having to prioritize whom to buy medicine for (it always ends up being the working adult, even if the kid is sicker, because if you don’t keep the worker healthy, everyone suffers and you can’t later take sick timmy to the doctor because you ain’t got no copay money), etc. Just because I own a cell phone with an internet connection (as required in order to respond to my job application emails – how else can I get a job these days?) doesn’t mean there isn’t quite a bit of overlap in the experience. Just because *you* are able to live comfortably despite a pandemic doesn’t mean the experience is universal.

That said, wear a mask and social distance, that’s just common sense on how to survive a pandemic and has nothing to do with the greater reality that our society is, like Spartan society, structured to benefit the few at the expense of the many, causing widespread preventable suffering and despair.

Not sure its entry fair to the realistically very stable Athenian democracy. to say

“with just two major breaks, consisting of just four months and one year”

Only one was internal. I don’t think an imposed government by outside power after loosing a total war counts.

Also does not the stability of the Roman Republic need an asterisk for the social war?

I’m sure Bret would count the Social War as a break in the stability of the Republic, but that was around 90BCE, *after* the end of the stable period he’s counting.