This post is now available in audio format here.

The last several weeks looking at Sparta have been pretty grim and heavy, so let’s lighten the mood by having some pointless, nit-picky fun. We’re going to talk about the comically nonsensical logistics of the “Battle of the Goldroad” from Game of Thrones (S7E4), commonly just called the ‘Loot Train battle.’

We already saw, with the “Siege of Gondor” series, that making fantasy armies obey the rules of logistics is actually not too difficult or excessively limiting in terms of story potential, but it does require a bit of forethought and planning by the story creator to manage distance and time in a way that is plausible. In the Game of Thrones/A Song of Ice and Fire universe, this is all the more important because food is a key resource and a primary concern of the characters at this point in the story as winter closes in. It is even more important when food is essentially the key resource being fought over.

Which brings us to Game of Thrones, season 7, episode 4 (“The Spoils of War”). In the South, the main action of the episode concerns Jaime Lannister’s campaign against House Tyrell – his plan was to sack their capital of Highgarden and loot not only their treasury but also secure the extensive food production of the Reach to supply Lannister armies and the city of King’s Landing through the on-coming Westerosi Winter. While we might not normally expect a keen attention to logistics, here logistics are the entire point of the whole campaign.

So we’re going to look at how plausible – or implausible – Jaime Lannister’s plan is. Assuming everything had gone right – could this plan have ever worked?

For those thinking about our three levels of military analysis – tactics, operations and strategy – what we’re doing today is entirely on the level of operations: how to get an army to and from the battle in the right amount of time, with good supplies, and in one piece (we’re going to look at the tactics of this battle next week).

(Units notes: I tend to work my logistics analysis in metric, because I prefer it. However, I leaned on Chase, Firearms a Global History (2008) for some very simple and straightforward rule-of-thumb-numbers (to keep this post from becoming a novel) and he uses imperial units, so there will be some converting between the two. I have tried desperately to hunt down any and all math errors here, but apologies in advance for the ones I inevitably missed.)

As always, if you like what you are reading here, please share it; if you really like it, you can support me on Patreon. And if you want updates whenever a new post appears, you can click below for email updates or follow me on twitter (@BretDevereaux) for updates as to new posts as well as my occasional ancient history, foreign policy or military history musings.

Problems of Geography

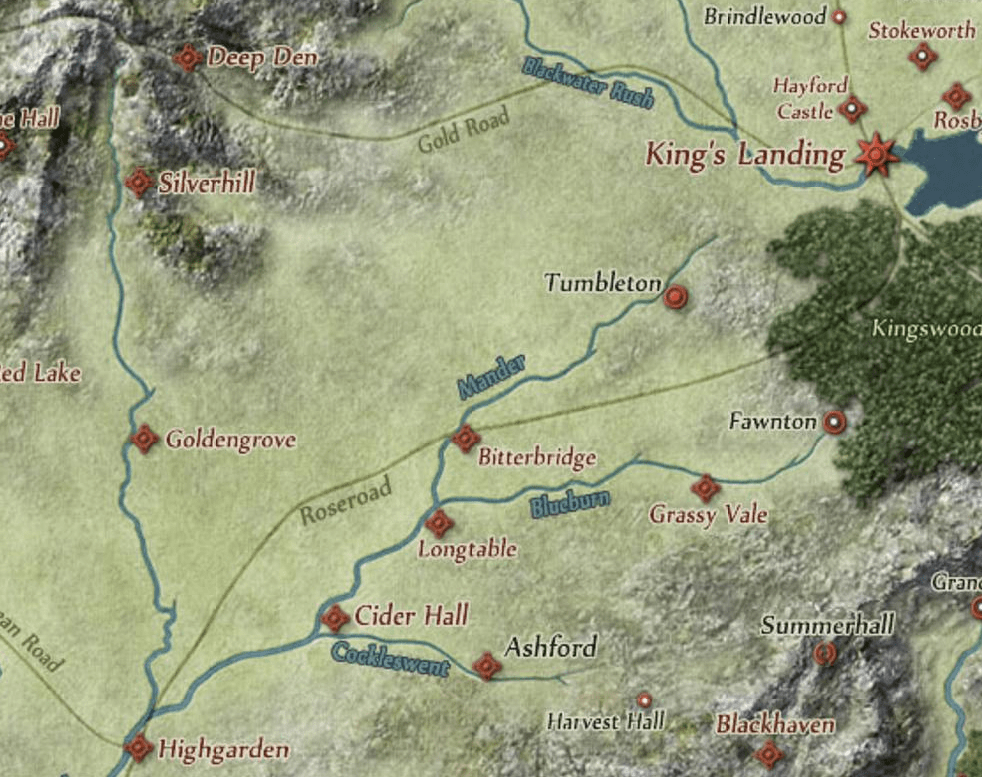

The first problem is trying to figure out where the battle took place. Despite the fact that the show opened with a map every episode, a strong mastery of the geography of Westeros was not one of the strengths of season seven. The loot train in question is evidently traveling from Highgarden to King’s Landing; given that the battle is name-checked as the “Battle of the Gold Road” later in the series (S8E6), it is safe to assume that the loot train eventually went down the Gold Road to get there.

Following this map of the major road network of Westeros – and as will soon be very apparent, this army is going to need some very major roads – the only real route then is for the loot train leaving Highgarden to move North along the Roseroad, but cutting north before Bitterbridge at the Mander, riding that minor, unnamed road north to the Goldroad, and then following that to King’s Landing.

This is a long detour. Getting any clear sense of distance in Westeros is really difficult – it is hard to pin G.R.R. Martin down precisely on the size of basically anything (I suspect he is being intentional about this), but you can reverse-engineer some of the maps with known distances to get some basics. From Highgarden to King’s Landing on the Roseroad is c. 760miles while going from Deep Den to King’s Landing (the Gold Road) is 560 miles. Westeros is huge – and also (we may assume by the army-size numbers we see) quite sparsely populated.

Now an army with wagons might move around 12 miles a day, making the trip from Highgarden to King’s Landing along the short route (the Roseroad) around 63 days long. But, again, Jaime at some point apparently gets up to the Gold Road, which looks to add around 250 miles to the trip by taking the indirect route (I assume he avoids the mountains and doesn’t ford any rivers with his massive train of wagons), adding 21 days to the trip (around 250 miles), making the entire trip 84 days. Nearly three months!!

That detour – hopping up from the Roseroad to the Gold Road is also going to be a problem for another reason. It’s hard to tell from maps of Westeros, but that land seems to be a lot less densely settled – the show represents it as open grassland. On the maps, I’ve never seen a major settlement in that area, and the topographical map makes it look like pretty rough country. If the population density is low, that is probably fatal to this operation (though to be fair, the massive size of the Kingswood poses the same problem on the Roseroad proper).

Now, Jaime Lannister says something about not going back by the normal route – presumably trying to outsmart their enemies – but this is a terrible plan. The thing is, armies move along predictable routes not because generals are stupid and predictable, but because the tremendous logistics demands they create mean that only a handful of routes are often ever really available to large armies. So let’s take a minute and talk about:

How Big is the Loot Train?

It’s actually best to start with the loot in the loot train, for reasons that will rapidly become clear. Jaime isn’t leading an army on campaign, after all, he’s escorting a large shipment. The entire point of this attack was to seize money and food to supply King’s Landing. The money was presumably fairly compact, but food is not. We’re going to be generous – at every stage in our calculations – to the Lannister plan (to show that it is unworkable under all assumptions), so what is the minimum significant amount of food that they could be moving?

Evidently the looted food supplies are enough to be meaningfully significant for King’s Landing, a city of 500,000+ people. Moreover, that core grain being carried needs to actually get to King’s Landing – it does no good if it is all eaten en route. But we’re about to see why it would be impossible to supply King’s Landing by land over long distance. Let’s assume the absolute minimum for ‘significant’ food imports to the Crownlands is enough to feed King’s Landing for just one month. That is (as per my previous math), 8,500,000kg of grain, or roughly 9,400 tons. For just one month.

Obviously, a real operation to supply the city and its garrison in any meaningful way would need more food than this, but again, we’re trying to be very generous to Jaime. Now, for a real world historical comparison, the Roman state under the first emperor Augustus supplied Rome with some 12 million modii (a Roman unit of dry measure; 60 modii per annum to 200,000 households) of grain per year, which comes to about 80.64 million kg of wheat (a modius of unmilled grain is around 6.7kg). That might better represent a truly significant food import for King’s Landing. That food supply, called the annona, was imported almost entirely by sea, for reasons that will rapidly become obvious (it was also a massive project requiring resources and administration which were not trivial for the Romans and quite clearly would have been wildly out of reach for Westeros).

Jaime is moving this food in wagons, which is absolutely the most efficient ground transportation option he has. Let’s assume each wagon holds around 1,400lbs of food, pulled by two horses. We could make this more efficient with different draft animals and bigger wagons, but I’m trying to keep these figures fairly simple; moreover if we were doing that, we shouldn’t be assuming (as we are) that the food is all nice, neat portable and high-density grain, and we’d have to talk about loss and spoilage – let’s just say that our fairly simple set of assumptions here favors Jaime (because they do). So Jaime needs to move 9,400 tons of food in two-horse, 1,400lbs wagons.

Also – did I miss something, or has Westeros not yet developed wheel-and-spoke technology? Why are all the wheels solid donuts like this is the Mid-Bronze Age?

Let’s start doing some math. Assuming 1,400lbs per wagon, that means we need 13,500 wagons, with 13,500 wagon drivers and 27,000 horses.

That’s…a lot of wagons. Now the roads we see Jaime moving down are limiting him to a single-file line of march with his wagons. How much space does that take up? Well, a wagon of this size is usually around 10 feet long, plus maybe another 8 feet for the horse, and we should assume while moving a few feet of clearance before the next wagon, so let’s say 25ft of road-space per wagon – note that we have not yet added the army to the road. This is just the wagons full of just one month’s food for King’s Landing. Now, Jaime’s wagons move single-file (in part because of the bad roads), but let’s make things even easier on him, and double them up, so we fit two wagons in each 25ft space, meaning the wagon train – again, no army yet – covers 168,750ft or 31 miles.

That’s a problem: this wagon train is so long that even without the army, even without spare baggage for the soldiers, even without supplies for the soldiers, it is so big that the back of it won’t even have been able to leave camp before the front of it has stopped for the day. Jaime and Bronn express concern that the front of the army wouldn’t be able to reinforce the back if it was attacked, and they’re not kidding! It would take three days for the front of the army to turn around and march to the back, or vice versa.

This is clearly unworkable. As we’ve discussed before, army trains this large need to be split up. Otherwise, the army ends up slowing down – which, for reasons we’ll see in a moment, is very very bad.

So let’s split our wagon-train into three groups, each just short of ten miles long and move them separately, but down the same road in sequence – Randyll Tarly is very clear that the front of this column is moving down the same road as the rest of it and has already reached King’s Landing. Now that comment struck some viewers – who knew a bit more about the geography – as insane, because the back of the column is evidently not yet over the Blackwater, but it actually makes sense. These individual components may be days apart moving down the road.

So we now have three armies, instead of one, but we at least now have a more-or-less functional marching order (our ten-mile long columns are still not fantastic and would probably have to be subdivided further, but lets keep thing simple). What about food?

(Note: leaving the army train single-file doesn’t impact our logistics calculations at all, but it would mean further sub-dividing the army to keep the columns less than the daily marching distance – I went with a two-file, three-division setup because it more closely matches the stated strength of Jaime’s force. Now if we want to suppose a single-file army with six 10,000 man columns moving these wagons, that impacts our logistics by making them even more impossible. Once again, we’re going to make a set of contrivances that favor Jaime, so it is even more disappointing when he still fails; just like in Season 8.)

Loot Train Logistics!

We start with the soldiers, because we can hold the number of them constant. Unfortunately, we don’t really have any numbers: the wiki claims that there were 10,000 Lannister soldiers and 100,000 Dothraki at the battle. That second number is absurd – there’s no way Jaime would even for a moment think he could hold outnumbered 10-to-1 by an army of steppe nomads. By the look of the fight, he might have been facing even or near-even numbers.

But 10,000 for the Lannisters makes a lot of sense. The main Lannister field armies have been quoted at 35,000, Jaime presumably brought as much as he could to attack Highgarden; if he split those 35,000ish men into three groups, then a rear-guard force of 10,000 would be pretty reasonable. So we have three armies, each with 10,000 men (yes, I’m rounding 5,000 infantrymen out of existence, we can say they were a garrison left in Highgarden if it bothers anyone) escorting this train of wagons to the destination.

(As a side note, that also makes a lot more sense than having a wagon train with more wagons than guards. This way, we have about two-and-a-quarter infantrymen per wagon. That’s still insanely wagon-heavy, of course – it really ought to be something like six-per-wagon at minimum, but there it is.)

Now, each of those detached armies is going to also need wagons for its own baggage train – additional equipment, supply storage and the like. One wagon for every 20 soldiers is a reasonable low-end figure for all of them, which means adding 1,500 wagons – 500 for each detachment – to our total.

That brings the entire, three-detachment column to a total of 15,000 wagons with 30,000 horses. We should add a few more horses to account for spares – this is a long journey (spare horses are necessary for military activity; a knight would have, for instance, generally gone to battle with at least three horses), so let’s assume a low-ball figure of 33,000 horses – one spare for every 10 horses (which will also have to cover our knights and scouts).

So the mouths we have to feed are 33,000 horses, 30,000 infantrymen, 15,000 wagon drivers. In practice, an actual army would include a lot more with it – there would be a siege train of equipment, as well as camp followers, sutlers, servants, and other non-combat personnel. In many cases, these army followers might exceed the size of the army itself, but I don’t want to over complicate things, so we’ll stick with just the army and the loot train itself.

What is the per-day food demand of that force? Well, we might suppose each man eats around 3lbs of supplies per day and each horse 10lbs (the sort of horses agrarian societies use are too big to subsist entirely on grazing and typically split their food requirements roughly half-and-half; thus the horse demand doubles to 20lbs if we take this army anywhere without lots of grass), so the whole force eats 465,000lbs (c. 210,920kg; 330,000lbs for the hoses, 135,000lbs for the humans).

Now, that army absolutely cannot carry the food it needs with it. It’s reasonable to suppose that each infantryman might carry around 30lbs of supplies (along with maybe 50lbs or so of equipment), which combined with the supply wagons (the ones not bound for King’s Landing) might give the entire force 3,000,000lbs (1,360,777kg; 900,000lbs on the infantry, 2,100,00 on the wagons) of supply capacity: enough for just six and a half days deficit (which it will need to make the ‘hop’ from the Roseroad to the Gold Road). Adding more wagons – as we’ll see in a minute – does little to resolve this problem over any significant distance (because the horses and driver eat the food in the wagon), so the army must forage as it moves.

Now we should be open about what ‘forage’ or ‘live off the land’ means here: it means confiscating – typically by force – food from the local farming population (I hope at some point to talk in a bit more depth about what the experience of that – from both ends – might be like, but that day is not today). That often entailed sending armed men – typically on horseback, although Jaime seems quite limited in this regard – to break into houses and storehouses to steal the food for the army. Consequently, this army can only go places where the local population density ensures that enough food will be available for confiscation. The margin for error here is small, because the army’s carrying capacity is limited – running a small deficit for a few days in a row could be catastrophic.

(Pedantry note: you may argue that Jaime could make up short-term deficiencies by depleting the ‘loot food’ and then refilling it later, but this defeats the entire purpose of the loot train, which is to increase the total food supply available in the Crownlands. If Jaime is refilling his wagons with food from the Crownlands, he might as well have saved everyone the trouble, and left his thousands of horses and wagons back in Highgarden, and just focused on a tax reform plan for the farmers of the Crownlands.)

Randyll Tarly’s advice to whip stragglers was probably kind: better a beating than a slow death from starvation.

So the question is what kind of population density does Jaime need? His column is moving at c. 12 miles a day and is composed almost entirely of infantry on a single road; if he’s lucky, Jaime might be able to ‘sweep’ the food within say, 5 miles on either side of his route, meaning that he forages 120 square mile per day (we don’t multiply this by three because each detachment is moving down the same route – in practice all of the foraging will be done at the front of the column, with the surplus left in depots to be picked up by the detachments further down the line).

A good rule of thumb for foraging operations is that they can pull in around 10% of the food production (annual) in the countryside without triggering real starvation (which Jaime cannot do because he needs the future production of these farmers to feed his capital – moreover, attempting to starve the route would also probably produce the sorts of resistance – like food concealment – which would negatively impact foraging anyway). Importing some dietary requirement figures for the pre-modern world, we might then expect that Jaime is going to be able to filch around 25kg of food from each farmer, plus or minus. So he needs to forage 8,437 farmers each day (to hit his 210,920kg requirements); with a 120 square mile sweep, that means he needs a population density of 70 per square mile.

And that figure is probably the death of this operation, no dragons or dothraki required. As discussed fairly ably by Lyman Stone here, medieval population density was not generally this high and it certainly didn’t maintain that average density over 900+ mile stretches of varied terrain. Lyman notes using some population estimates from 1000 to 1500, population figures from the single digits up to the low 90s (with the highly urbanized Low Countries as an outlier over 100; note that this runs against the standard ‘fact-sheet’ used for this purpose). Jaime’s march is the equivalent of a trip from Madrid to Frankfurt, and the chances of maintaining the consistently above average densities he needs are basically nil.

For different points of comparison, the population density of Roman Italy during the first century was probably around 100 per square mile, but it was importing vast quantities of grain from Egypt and North Africa to maintain that. On the flip side, the American South in 1861 was only c. 20 per square mile. As Lyman notes, medieval France ranges from 36 to 68 per square mile, depending on when you ask the question. In the early 14th century, at the moment of the Black Death, the European population density probably peaked around 20ish per square mile over the whole continent before falling (and then rising again dramatically in the early modern period, but that’s a story for another day); obviously there was big variations in that – but given that Jaime is covering such a massive difference, a big-damn-average is more relevant than cherry-picking high outliers like the Low Countries.

In short, Jaime’s convoy can only move through areas of dense settlement – rich, urbanized agricultural land. Quite frankly, outside of the Crownlands, that kind of human terrain doesn’t exist in much of Westeros, which is by all appearances (judging land size against army sizes, reported city sizes and the concentration of major settlements) vast, but fairly sparsely populated. It will not hold for trips off of the main transport routes or beyond key agricultural areas like river valleys. And it absolutely will not hold for a 900-mile trip anywhere – if Westeros had a 900-mile long strip of densely urbanized 70+ people-per-square-mile-density settlement, it would be a very different society than the one described to us (if for no other reason than that millions of people would live in that zone, with a level of urbanization more like the late early modern or the Roman imperial periods and less like the late Middle Ages).

Can’t He Add More Wagons?

In a word, no. Or more correctly, he can, but it isn’t going to help much.

Let’s make some terrain assumptions. At least some of Jaime’s route looks like this:

That’s an effective population density of zero. It’s open grassland. And it is clearly not a small slice of the route. Judging by the maps I’ve found, the area between the Roseroad and the Gold Road is not – at almost any point – densely settled; there don’t seem to be any significant population centers there; the population of the Reach is concentrated further south, on the river Mander (which makes a good deal of sense, geographically – people tend to live near rivers).

Let’s be very generous and assume that the average density after Jaime leaves Highgarden is twice the European average in the 14th century, so 40 per square mile – because sure, Highgarden is probably densely settled, but the area south of the Gold Road is basically empty and some of his marching terrain is open steppe. How many supply wagons does Jaime need? The question is actually a touch more complicated than it sounds.

(Now you may ask, “What if Jaime learns to read a map and takes the Roseroad the entire way like a sane person. First, I would say that everyone in season 7 needed some remedial map training, but second: it doesn’t actually help all that much. He still has to get through a couple hundred miles of Kingswood, which is densely forested and so does not include lots of farms or settlements – it poses many of the same problems that grassland would.)

The trip – as noted above – is 84 days long and he’s going to forage 96,000kg of supplies from 4,800 people each day, leading to a deficit of 114,920kg per day since he requires 210,920kg to feed his force; we ought to account for spoilage, but let’s assume the grain is magic and there is none. Over the entire 84 day trip, his total deficit will run to 9,653,280kg of supplies, which utterly swamps his 1,360,777kg of carrying capacity. He can’t bring anywhere near enough food to bridge the gap to King’s Landing – even if the last several hundred miles of his trip are dense farmland, his army will starve before it gets there.

Ok, so let’s double his supply wagons, from 1,500 to 3,000 (not including the King’s Landing food, which needs to, you know, get to King’s Landing). Our storage capacity goes up by 952,543kg (2.1 million lbs) to 2,313,321kg, but our food consumption increases by 15,650kg (34,500lbs) from the added drivers and horses – but we can’t forage any more people – meaning our daily deficit now runs around 130,570kg, so the total for the 84 day trip is 10,967,880kg, nearly five times what we can carry. We’ve gotten almost no closer to our goal!

Well then enough of this small ball stuff, what about 10,000 wagons! That brings our supply capacity up to a tremendous 6,391,116kg (14 million lbs), but our daily food consumption increases by 88,677kg (over the original, 1,500 wagon setup), meaning our daily deficit is 203,597kg, or 17,102,148kg over the entire trip; we still have a massive shortfall of nearly 11 million kg. Not only that, we now have a baggage train nearly 80 miles long and chances are that we are beginning to run seriously short on grazing near the road – which can either increase food consumption, or slow us down, both of which makes things even worse. Oh, and also someone at the beginning of this venture needs to source something like 50,000 horses and 23,500 wagon drivers with their wagons – in a recently captured and sacked castle, because I dearly hope you didn’t also bring all of those horses (with food and supplies) all the way out with you too. Good Luck. With. That.

Conclusions

This is the fundamental logistical problem of the pre-railroad era: everything you use to move food that is not a boat, eats the food, and does so quite quickly. Armies were thus restricted to sticking to areas where their food could be gathered locally, or sourced by sea or river transport (the latter way way more efficient – a single ancient grain freighter from the Roman period might bring in several hundred tons of grain in a single run).

I want to be clear here: the logistics burden that makes this impossible is not the infantry, but rather all of the horses pulling the wagons full of grain that – from a logistics standpoint – is useless because it needs to reach the end-point uneaten. Those horses are the massive logistics burden that breaks this plan.

Now, could you modify our assumptions further in order to get an operation that works in some minimal way? Reduce the number of soldiers, make the wagons much bigger (perhaps the one-and-a-half-ton logistics wagons common in the Union army in the ACW), use more efficient pack animals (mules, mostly) and pull up the population density of the route above medieval European norms and you can eventually get an operational plan where everyone doesn’t just die.

But the entire effort is rather pointless anyway. Even if Jaime could somehow string together a route with high enough population density from beginning to end to get his entire army there – this is under the sensible, 1,500 supply wagon model – he’d still be wasting everyone’s time. The army would have eaten 17.7 million kg of grain merely to deliver 8.5 kg to King’s Landing – and every bit of the food they foraged along the way (which again, would be most of it) would have been far easier to move to King’s Landing than the loot from Highgarden!

And all of this effort – the 33,000 horses, thousands of drivers, the three months of marching, not to mention the likely many thousands of porters and loaders required along the way – could only supply King’s Landing for a month. Making it through a normal, Earthly winter would require at least three times as much, much less Westerosi winters that can last for years.

More broadly, this ought to put the insanity to the idea that The Reach and Highgarden could actually supply King’s Landing normally in peacetime using overland transport – the cost of moving that grain these vast distances overland would be insane, because massive amounts of food would have to be expended to maintain the transportation network for just a trickle of grain to reach the other end. It would actually be far cheaper to ship the grain down the Mander, send it for thousands of miles around the Summer Sea, up the Narrow Sea and into Blackwater Bay.

Now, when I’ve made this sort of criticism in the past, I’m often asked, how can this be fixed? Here I’m actually at a bit of a loss – short of massively re-designing the geography of Westeros. The core problem is that Westeros – at least Southern Westeros – is presented as culturally and economically interconnected, with shared institutions and cultural values and intertwined economies. Because here is the thing: until the development of railroads, large interconnected areas like this – like the Roman, Ottoman Empires, or Han China – were united by water and seperated by land because ship transport was so expensive. Horden and Purcell (The Corrupting Sea) describe the coast of the Mediterranean as like an archipelago because naval transport was so much more important than land transport. In China, that role was served by the large navigable rivers which all connected to the same navigable coastline.

In short, for Jaime’s plan to make sense, the Mander needs to have its outlet not in the Sunset Sea, but in Blackwater Bay or Shipbreaker Bay – the opposite direction. If that was the case, his army could shadow a fleet of river-barges following the wide, navigable river down to the coast, carrying many thousands of tons of supplies. This is how, for instance, the Romans seemed to have managed massive military concentrations in Illyria and Pannonia in 6-8AD – the armies were supplied through bases on the Sava River, which was navigable up to the major Roman legionary base at Siscia (modern Sisak, Croatia). Supplies for the armies flowed up the Danube to the Sava (a tributary of it), so that the legions ate while the rebels starved.

(Note: because I am sure someone will ask, “What about the Mongols, with their huge, entirely land-based mega-empire?” The short answer is that for steppe nomads, like the Mongols, this logistics equation works on an entirely different basis, with a completely different set of constraints. The long answer will probably have to wait for us to take a closer look at steppe nomads and how poorly represented they are in fiction – probably beginning with the Dothraki.)

How many wagons? Oh. Oh my no. But I’m going to fly over there on my dragon and laugh at his army as it falls apart from starvation. It’ll be hilarious.

But with the geography of Westeros as it is, it doesn’t work. Put quite simply, Jaime’s plan is stupid and Daenerys could have saved herself and everyone else some valuable time by just staying in Dragonstone while Jaime and his army collapsed from starvation.

Had she done so, it would also have saved us from the tactical train-wreck of a battle that is the Battle of the Gold Road. And that’s what we’re going to nit-pick on next week.

Hello! I’m from r/ASOIAF, where your blog was posted here: https://redd.it/ddatl6

I posted this comment over there, and I’d be interested in your response:

___

This was a good read, but these figures…

>Now an army with wagons might move around 12 miles a day, making the trip from ***Highgarden to King’s Landing along the short route (the Roseroad) around 63 days long.*** But, again, Jamie at some point apparently gets up to the Gold Road, which looks to add around 250 miles to the trip by taking the indirect route (I assume he avoids the mountains and doesn’t ford any rivers with his massive train of wagons), adding 21 days to the trip (around 250 miles), making the entire trip 84 days. ***Nearly three months!!***

… can’t be right. Not with the show canon, which is the basis of this whole analysis.

From the pilot, we learn that Robert and Cersei and the entire court, with all their retainers and their massive carriage with their young family… All those people and supplies travelled from ***King’s Landing to Winterfell in a month.***

>Take me to your crypt. I want to pay my respects.

>We’ve been riding for a month, my love. Surely the dead can wait.

King’s Landing to Winterfell is much, much farther than Highgarden to King’s Landing. At least double the distance, which means Highgarden to KL shouldn’t take more than two weeks along the Roseroad. Even with the detour to the Gold Road, Jaime’s transport should not have taken three months.

There must be something massively wrong with this blog author’s scale, the map he used or something in his calculations to arrive at such a disparity.

And of course, if this point is incorrect, it will have huge trickle-down effects for all his calculations. I don’t think Westeros is as large as he’s assuming it to be, not in the show anyway.

Welcome from Reddit!

I would suggest that the problem here is that Martin does not understand how rapidly things move, or he didn’t plan his geography well, or both. In interviews, he’s indicated that he “doesn’t like to be pinned down” on how fast things move. All of the maps of Westeros, including the one from The Lands of Ice and Fire – the official publication – use the known length of the Wall (100 leagues = 300 miles) as the calculation basis for the size of the world.

Based on that, it should be something like 1,600 miles from King’s Landing to Winterfell. The figure of roughly a month for that trip isn’t actually impossible, it’s just unlikely. They’d need to move close to 50 miles a day, which is possible for cavalry, but probably not for carriages. But one might imagine a slower speed – around 40 miles a day – which might produce a trip that would be summarized as “a month.” That said, that’s a hard ride for agrarian cavalry, so it seems unlikely to me. Also, you would definitely not ride that distance, you’d sail to the White Harbor and then ride up; it would be quite a bit faster.

Far more likely is that Martin made the basic map and gave out some of the known distances without a full sense of what making his world so large would entail in terms of movement and logistics.

This is why I think Martin’s version of Westeros is substantially larger than the one depicted in the television series. As you say, Martin is loath to give out definitive distances or times in his narrative, but the show does volunteer certain anchor points, namely the one in the pilot.

If we take Cersei at her word, and in the show universe it really does take only a month to travel from King’s Landing to Winterfell (with the royal children in a carriage, at an easy pace) would that make the logistics of Jaime’s loot train more plausible, given all your other calculations?

There’s a far simpler solution to that problem.

While show Robert says he was riding for a month, nowhere is it said that this was the whole journey or it was one month since they left Kings Landing. It’s kind of self evident that there would be stops, if only because the media trope this is drawn from involves stops. Visiting important people along the way.

But also because the books, which were closely adapted for the first couple seasons, tell us explicitly they stopped along the way. Visiting important folks along the route as they went.

You can only use this statement to gauge the distance if we assume a month is how long it took to cover the full distance. And I don’t see any reason to.

I thought the point of the loot train was the pay off the Iron Bank, not just shipping food which would need to be shipped every single day

I would like to note here that map makes no sense either. It would be good idea to make an overview of all problems of mapbuilding of Westeros, but one thing I have an issue with is this:

https://acoupdotblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/10/got-map.png

Roads tend to follow rivers. Specifically, river valleys, as rivers tend to make terrain more passable. Look at Roman road network:

https://transportgeography.org/?page_id=1060

there is a river near it, it just doesn’t follow the river precisely.

but the fact that there *is* a river near the route taken, and headed in roughly the right direction, makes the whole idea of moving things by wagon overland idiotic. the operational plan, if fixated on going shortest distance instead of sailing it all the way around the southern part of the continent, should have been to use his army to secure control over the forts along the Mander river, all the way up to around Tumbleton. barge the supplies down the river, *then* use carts to move the supplies in a constant cycle of convoys between the Mander and barges on the blackwater. would have been much faster and simpler.

Indeed. Basically all trade in Roman and Medieval times moved by the riverways… anything else is simply too expensive. Roman roads were used by traders (over short distances) but their main purpose was military and administrative in nature.

I didn’t expect Tsiolkovsky’s rocket equation to show up in medieval logistics! This problem — everything you use to move food eats the food, so you need more food, but then you need to move that food too — is the defining problem of sending things to space, with rocket engines and rocket fuel instead of horses and grain.

You didn’t show the general formula, but it turns out the total amount of food you need grows exponentially with the rate of consumption of the food. This explains why you need to eat so much food to deliver a paltry amount.

You can argue that the journey was shorter, as people have done in previous comments. You can question the 500,000 mouths to feed: there were some cities that size in China around 1300, but it’s still enormous for a medieval city especially if the countryside is so empty. But neither will help much: they only have a linear effect on the amount of food and number of wagons.

But boats help enormously. The crew still has to eat, but eating even a little less has an exponential effect on total food needed. Maybe Westerosi grass is magical and can sustain horses alone?

The equation also suggests a novel solution: The way to get higher mass ratios in rockets (that is, more fuel or food to be used on the way per delivered bit of mass or horses & food wagons to the final destination) is to use staging: Use a large piece of metal to get a mass ratio of 10 for stage 1, then you throw that metal away and your amount of mass to move is lower and you use stage 2 with a mass ratio of 10, and your total mass ratio is the two ratios multiplied so 100!

To use that here would mean that as wagons get depleted of food, you tell the drivers so sod off and that you won’t feed them anymore, and if they complain you will kill them. The slight issue is finding wagon drivers willing to do a job that ends with “and then you die of starvation”

pretty sure with years long winters being common that cannibalism would be common. So, when the wagons become depleted you eat the drivers.

What else would Brienne wear, a dress? Dresses are for girly-girls and book characters! If Brienne didn’t present herself more masculinely than some of the actual men, how would the viewers know she was supposed to be un-girly?

…sorry. That adaptation annoys me the more I think about/remember it.

Or, for that matter, read. That’s another little detail I’d never noticed or had pointed out to me. I guess we should expand the historical-inspiration window all the way from the effing bronze Age to the Renaissance.

But this is a problem we can lay at George R.R. Martin’s feet. (I’d argue the showrunners exacerbated it, but…what’s the point? It’s far from the worst thing they did.) Martin, for all his strengths, doesn’t have a good sense of scale.

I remember reading a story from early in the show’s production, when Martin saw a visualization of the Wall and asked why it was so tall, was told it was 700 feet tall like in the boos, and commented that he wrote it too big. Sadly, my attempts at finding this story, or even a quote from it, have failed, so…take it as anecdotal evidence of an anecdote before admitting that, whether or not the story is true, he definitely wrote the Wall too big.

(I did find a bunch of interviews talking about the Wall in more general terms, where Martin said that things are bigger and more colorful in fantasy, so he took Hadrian’s Wall and made it three times longer, 700 feet tall, and made of ice…which kinda makes me want to write a high fantasy story set on an island inhabited by thousands or hundreds of people, with a “wall” even shorter than Hadrian’s in both senses and made of something even more mundane than stone. Maybe turf?)

That story is mostly right, but it was the fact that the Magheramorne Quarry’s cliff was 400 feet tall that made him realize that the Wall at 700 feet was too tall. It’s from my report of visiting the set with GRRM during the filming of the first season: https://www.westeros.org/Features/Entry/Belfast_Set_Visit_Report_Part_5_and_Last/

Looking at this much later, but it seems at least vaguely plausible to me, psychologically, that Brienne of Tarth might choose to wear her armor in situations where it wouldn’t otherwise make a lot of sense. Especially if she is (as I gather she was in that scene) writing stuff about Jaime Lannister in the Kingsguard annals. The Kingsguard, specifically has this whole ultra-chivalric culture and legacy, and Brienne might well have felt that she was under some kind of weird obligation to armor up.

I could be wrong.

I am greatly enjoying going through your backlog, and while I was reading your question of how this logistical problem of connecting King’s Landing with Highgarden could be fixed, I was inspired by the idea of a canal.

Specifically connecting the northern part of the river Mander to the Blackwater Rush by an artificial canal, as a means of explaining how King’s Landing is capable getting any significant food shipments from the south. It seems to me like the least invasive change to the topography and world-building that could potentially fix the issue. All that being said, I lack the required knowledge to judge if the existence of such a canal, and the subsequent moving of troops and supplies by boat would actually make the discussed expedition feasible.

As for building said canal, admittedly, I find it quite unlikely that the society described in the book/series would be capable of such a large undertaking of civic engineering, but one could just hand-wave this away as some act of fantasy magic, as seems to have been done with a number of other monuments in the story. Food for thought.

The Valyrians were capable of some incredible (and probably magical) acts of masonry. I’m not sure if the post-Fall Targaryens retained enough Valyrian magic to pull off civic engineering that would make the Romans jealous, but the setting absolutely could have been written that way.

actually there was a historical precedent bearing a lot of similarity with this idea: the ancient chinese grand canal system. but it’s a disaster in more ways than one.

first, in westeros, the river mander and blackwater rush flow in total different directions. to build an artificial canal connecting such rivers is doable, but reckons a highly cost, because:

a) the government have to pay a huge fortune to just clear the clogging;

b) messing with the natural river systems, and the nature certainly would mess back. in the real chinese history and would-be westerosi scenario, the results are same:

whenever there was a flood in rivers like blackwater rush, the catastrophe would multitude in rivers like mander. and whenever there wasn’t a flood, there would be severe drought and soil salinization around river mander, to render the reach farmland into wasteland.

and that’s just natural ecologic cost, the economic and social costs would be way worse.

in the real ancient chinese history, to build and maintain such grand canal system, there has to be a government and social system so authoritarian that fall out of even reasonable modern political spectrum map. it just simply can’t be transplant in westero.

even when the canal is in place, the disasters are far from finished. the financial cost to run this canal system is literally dynasty-bankrupting, due to bureaucratic tardiness, waste, and corruption.

and eventually the central government in capital would just focus in keep the canal running and capital fed, ignoring all kinds of social problems the canal caused in surround areas so long as there was no full-blown rebellion. “small-scale” but demographic-noticeable banditry and famines and plagues are rules rather exception. in a word, the canal area became a wicked badland, and when the genocidal-scale mass rebellion finally blow out, there is nothing anyone could done about it.

Do you think it would be possible to build it at all in this case? Google tells me that the Mandar river runs north-south, which means that the map is showing the place where its headwaters end by King’s Landing. Rivers form out of collections of lots of little creeks running down out of mountains (or is there another way rivers start? I’m not a geologist…), so it seems to me that there must be a significant elevation change between King’s Landing (at sea level) and the point where there was a large enough river to float boats on–if it’s running south, then that’s on the far side from King’s landing of whatever mountains are in-between. If there’s not a river on the northern side already that can be used, it seems like it would take some pretty absurd feat of engineering. …Even if there is a river on the northern side, it seems like it would take some pretty absurd feat of engineering. Is it possible at all?

Does anyone know of some good (ideally relatively accessible) sources to better understand the, “truly staggering levels of military mortality in pre-historic societies” that Brett mentioned?

Read the first chapter of Azar Gat’s War in Human Civilization. Follow the footnotes for the hard data.

>On the flip side, the American South in 1861 was only c. 20 per square mile.

Out of curiosity, how does the math work out for Sherman going from Atlanta to Savannah? I was under the impression that he relied on forage to sustain his army on that march. Does the higher yield of modern agricultural methods completely alter the equation regarding food generated/population density? Or would Sherman have looted a higher percentage of civilian food stocks since he was exclusively in enemy territory (however, I don’t believe he had any intention to starve the Southern populace)?

I’ve seen that particular question for Sherman’s campaigns discussed in J.G. Moore, “Mobility and Strategy in the Civil War” in Military Affairs 24.2 (1960): 68-77. I’m sure there are things more recent, but I don’t work on the ACW.

Another ACOUP essay that takes on new relevance in light of the Russian invasion of Ukraine—in particular, the (related though distinct) logistical challenges faced by the convoy to Kyiv.

No it doesn’t. Medieval armies don’t work the same way as modern armies.

The situation isn’t the same, but this post highlights some of the same issues, including:

1) The fact that trying to run a huge army or caravan down a single linear roadway results in your forces getting extremely strung out over great distances, making them vulnerable to attack.

2) The physical limitations of having a very long, strung-out force mean that if something goes wrong at one point on the column (enemy attack, a truck breaks down) the rest of the force becomes an obstacle to any attempt to reinforce the threatened point.

3) Failure to attend closely to logistical details can doom a military operation that, superficially, might seem like something a more naive person would expect could succeed (“loot food from Highgarden to feed King’s Landing,” “entire Russian army tools up to take Kyiv”).

The details are different, but not everything is different.

Whether this is a reminder to Devereaux about a place he could link that fancy three-part logistics series or just a PSA to new readers who see the three-year-old Loot Train Battle post before last months’ logistics series…he did go into more depth. And there was much rejoicing.

Shouldn’t have posted that quite so quickly.

This (four-part) series also exists. Check the Steppe Nomads tag.

Hi, I want to thank you for the usefulness of this and a couple related articles. I run a game for a system called Exalted, and I have been having fun making the logistics of pre-modern armies an important plotpoint. The players are playing fantastic demigods, and dealing with faery monsters who feed on mortal terror, and while trying to free the slaves of the fae, learned that the mortal terror feeding was tactically relevant, since fae armies can feed on terror, they don’t need to carry food and supplies with them, combat and raiding itself sustains them.

I never would have had the idea to make this so important if your articles on this site hadn’t made me realize the incredible advantage that emotion-eating could be for fantasy armies.

So, thank you <3