This is the third part of a series taking a historian’s look at the Battle of Helm’s Deep (I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII. VIII), from both J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Two Towers (1954) and peter Jackson’s 2002 film of the same name. In our last part, we looked at the film-only cavalry engagement that proceeds the main action of the campaign (the assault on the fortress-complex at Helm’s Gate). This week (and next) we’re going to put the action on pause for just a moment (or, I suppose, two weeks worth of moments) and look in a bit more depth at how these two armies are organized and how that organization might impact their success.

I suspect for some readers, this may seem a frustrating delay before we get to ‘the good stuff’ of swinging swords and rushing horses (do not worry, we will get there), but battles often turn on more than just tactics. The tactical options an army has available to it are constrained by its organization – does it have the command infrastructure, the training, the discipline, the organizational culture to actually do whatever thing the commander might think of (and that’s without asking ‘is that thing within doctrine?’)? And in turn, that organization is constrained by even more fundamental questions of social organization, economic foundations, cultural values and even gender roles. In a sense, the army and the battle are like a multi-story building, built one floor at a time: the options for each new floor are shaped and limited by what the floors beneath you can bear. This is why military history, far from being just a history of battles, is a comprehensive historical approach that ought to enfold every other historical skill-set (and these days, increasingly does; military history is rather a lot more sophisticated now than it once was).

So this week, we’re going to go one level down and look at army organization in a situation (a vat-grown Uruk army) which is practically a thought experiment in army organization. I feel like I’m in physics class again and “assume Uruks with no society and culture” is the new equivalent of “assume an airless, frictionless vacuum.” Here the complications from more fundamental factors are minimal because the Uruks don’t have a preexisting society, though as we’ll see this poses real problems too. Next week, we’ll look at the organization of Rohan’s armies, where social organization plays a much stronger role in decisively shaping the forces Rohan can muster.

And as always, before we dive in, a reminder – if you like what you are reading here, please share it (I don’t advertise or search-engine-optimize, I get all of my readers by word-of-mouth); if you really like it, you can support me on Patreon. And if you want to be updated whenever new posts appear, you can can follow me on twitter (@BretDevereaux) or subscribe for email updates using the button below:

And with that out of the way – let’s march to Helm’s Deep!

We’ll talk a bit more about baggage trains when we talk about Rohan’s organization.

Organizational Systems

We pick up with Saruman giving a speech to his army and sending them off to war. Put a pin in Saruman’s speech – we’ll come back to the pre-battle speech (and the question of leadership and morale) a little later in this series. Right now, I want to focus on how the Uruk-hai are arranged here and what we can say about their organization.

First, it’s important to lay some groundwork as to what sort of army this is, because armies can be recruited and organized under a number of different principles, which can result in very different forces and force-structures. And I should note that none of these principles is necessarily all-around best, so much as (for reasons we’ll discuss below) they need to be fitted to the society and the mission profile. There is a general assumption that ‘long-service professional army is best’ – but ask the British how well that worked in 1914; no army is right for every road or every society. But the demands of leadership and organization, as well as the relative capabilities vary greatly between systems.

For instance, a tribal levy or a citizen militia (closely related forms, honestly, just derived from differently organized societies) might need relatively little organization or even drill to be effective on the battlefield, because they are so rooted in civilian society. Such an army can place less emphasis on formal officers, because the peacetime social hierarchy – which may itself be, to some degree, informal – asserts itself. Local big men or elected officials make natural leaders, their friends or colleagues make natural subaltern officers. At the same time, drill and discipline – which is often meant to create cohesion and stiffen morale as much as it is to train the manual movements of fighting – may be less necessary, because the morale force that holds the troops in the line (the cohesive principle) is derived from their relationships in civilian life – no one wants to be thought a coward in front of his friends, family and neighbors. Of course, drill might still be necessary if the dominant combat style demands it (a good example of this being the legions of the Middle Republic), but it isn’t what is holding the line together; at the same time, in some societies operating under this principle, key combat skills were dispersed widely in the population, either due to use in daily life (as with Steppe Nomads) or through social expectation.

And sadly, demagogues using narratives – often invented or false – of ethnic dispossession (“XYZ group took our <whatever> in the distant past”) is all too common as the spark of violence in the real world. I was struck, reading J. Stearn’s Dancing in the Glory of Monsters (2011) how frequently, at the root of violence and horror, were opportunists – including European colonial authorities – using (sometimes cynically, sometimes with sincere malice) such narratives. Once consecrated in violence, the narratives – true or not – made peace and development practically impossible, because they kept touching off new violence.

Of course this is not restricted to developing countries or far-away places, we see it in our own times and places.

(Terminology Note: some readers have been surprised that I use the term ‘tribe,’ thinking that it is universally a pejorative; I do not intend it as such. Rather, I use it because it is really the only good, precise term we have for a political grouping larger than a clan and not so nearly bounded by direct blood-ties – a tribe many consist of many clans, which may not even be directly related – that is not a state. Unlike ‘chiefdom,’ the term tribe allows better for the fantastic range of tribal government forms we see historically (not all tribes have clear, singular ‘chiefs). But to be clear, there is no value judgement here – a tribe is just one of several possible forms of larger-scale human social and political organization. When I say ‘tribe’ that just means ‘political grouping bigger than a clan which is not a state.’ Tribe is, in my experience, still widely used by archaeologists, anthropologists and classicists in this sense, if just because there is no other equally precise term).

At the opposite end of the spectrum (and there are quite a number of other systems we’re not discussing here, as well as hybrid systems; in a sense, every military in every era is its own unique beast), a professional army often needs to be very intensively organized and carefully drilled to be effective. Because they are fundamentally deracinated (meaning ‘uprooted’ in the sense of ‘pulled out of a society’), professional armies have to recreate those social structures, through complex layers of hierarchy, which tends to mean lots of officers (which in turn often make professional armies uncommonly good at very complex forms of warfare). Note that not only are the armies themselves deracinated (in that they tend to have parallel systems of organization, rather than overlapping with a society’s existing systems) but their soldiers are typically deracinated as well, especially in long-service professional forces where ‘soldier’ is an occupation that an individual might expect to hold for most of their adult life; those soldiers are, in a real sense removed from society in order to defend it. Such armies also often need quite a lot of drill and training, both to teach skills, but also crucially to form cohesive bonds within the unit to allow it to withstand the stress of combat. Boot camp is made intentionally difficult and draining so that the shared stress and suffering will forge the unit together – for a tribal levy, that process is less necessary (but may still be helpful) because daily life has already formed those bonds. Moreover, a lot more skill training may be necessary, because professional armies are often recruiting from comprehensively demilitarized societies and so cannot assume any preexisting military skills among recruits.

Why this long digression, you ask? Well, because it is going to explain why the lack of certain institutions and preparation in Saruman’s host represent dangerous failings while the lack of the exact same things among the Rohirrim (who we’ll discuss next week) do not. Put bluntly, Saruman’s host is a green as a Greek Loeb (both literally, I suppose, being orcs but also more importantly figuratively, in the sense of being very inexperienced) professional army and thus needs to be tightly organized, extensively drilled and thoroughly officered. And it very much isn’t any of those things.

Uruk Squares

All of which gets us back to Saruman giving a speech to his host, which is neatly organized into nice big rectangles. Parsing these formations is a bit difficult; my extended edition copies are the original DVDs (lovingly bought for me as gifts each year before the next film came out), rather than any sort of high-definition or blue-ray version, so when you freeze-frame, the clumps of Uruks basically dissolve into grey-black mush. Fortunately, there are higher resolution captures and videos floating around, so we can start to parse what the unit organization of this army might be like. I should note that I most certainly did not count every formation, but counted one and estimated the others from it.

Honestly, this picture could serve as the summary of all of my research – elites get in the way of me clearly seeing what I actually want to talk about, which is common soldiers and common citizens. Stop blabbing on about ‘the wise’ and ‘ringlore’ and tell me more about the exact duties of the most junior NCO and then give me a representative sample of them, with information on their heritage, civilian occupation, age, nuptiality, mortality and social status!

But let’s start with the obvious: this isn’t a military formation at all, but a propaganda one. Jackson is leaning not on military affairs, but on one very specific German film, Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will) to create a filmic language for ‘scary powerful bad guys.’ It was a piece of pre-war Nazi propaganda, and I really do recommend Dan Olsen’s video at Folding Ideas on the film’s framing, relative lack of artistic merit, and truly profound (and perhaps unsettling) significance for film. I think at some point on the blog, we’ll talk in more depth about the imagery of military power against the reality of it – and this sort of ‘men standing in squares’ will feature heavily – but for now I want to note that this scene is all imagery and not much reality. Nevertheless, we can learn some things by trying to sketch out the organization of this force.

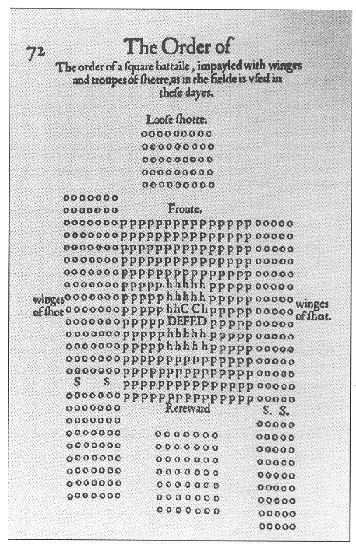

The first thing we can learn is that ‘tens of thousands’ (or ten thousand, as we find out the army later is) is a lot more than we may intuitively think it is. For reference, the block I highlight in the image below looks to be about 12 Uruks deep, and about 30 Uruks wide (so 360 Uruks in total). There are a number of blocks about this size (some larger, some smaller) in this formation, but I’m not sure there are thirty of them (counting myself, I only count about twenty to twenty five). Now, I am going to bet that the CGI team did their homework and that there are, in fact, 10,000 Uruks here, but that to make that number fit onscreen, a lot of the work is being done by compressing them quite tightly (these formations are uncomfortably tight, particularly in depth) but also by the larger blocks of troops in the back (especially the back left of the frame). 10,000 soldiers, drawn up in a 10-deep battle order (quite deep for regular infantry) would still stretch about a mile, assuming tight intervals and no spaces between units. Armies are big!

As an aside: you may expect me to complain about a 30×12 formation (as I’ve tended to be critical of that sort of thing in the past), but these Uruks wield pikes. While in practice standard infantry formations tend to be something like 6 to 8 soldiers deep (with exceptions for things like the fifty-deep column of Thebans at Leuktra ), pike formations are often formed deeper than other kinds of infantry, in part because long pikes can strike over the heads of the men (or orcs) in front of them, leading to less dead-weight-loss in a deep formation. Macedonian sarissa-pike formations were, as standard, 16 phalangites deep; early modern European pike squares were often around 15×15 (and sometimes more). Moreover, for all of their fury, these troops are green as the grassy fields (a point we will return to in a moment). Saruman would be right not to trust their inherent cohesion; deeper formations often give a sense of mental security to the troops in them, which can improve morale and cohesion. You feel safer with a thicker, deeper formation (even if you aren’t, necessarily).

I am a bit surprised that this army, which is freshly mustered, has such irregular units (what, for instance, is the purpose of that unit formed up in the center in a thin line just three wide?); some are much larger, some are quite a bit smaller. As we’ll see in a moment, this is exactly what we’d expect from Rohan’s army, where the tactical and organizational units are organic products of the underlying society, and thus likely to be very irregular, but Saruman has grown this army and I think it is strange that someone with “a mind of metal and wheels” (TT, 90) didn’t try to enforce some sort of standard organization. Still, if these units mostly range from something like 300 to 500, that’s would make sense as a roughly battalion-sized element (or, if you prefer ancient units as benchmarks, the Roman cohort was about 500 men, and the Macedonian syntagma was 256).

We get a better look at a smaller unit of Uruks earlier when Merry and Pippin are being carried. The unit moving them has clearly taken some casualties (in the fighting at the Anduin against Boromir) and we never get a clear enough shot to make a count of what is left. But we can see in the film that this unit had not only a lead officer (slain by Aragorn in Fellowship) but also a second in command who takes over, seemingly seamlessly, and is in position to speak for the unit against the Mordor orcs who arrive. Overall, it seems like a roughly company sized (hundred-ish) unit.

Book Note: Assuming that the film follows the book details, we actually get quite a lot more information. Boromir slew “twenty at least” (TT, 18) of the force; Legolas and Gimli some number more (but perhaps less than Boromir, given that they stand ‘amazed’ at the scene, TT 19). The remaining force, counted by the hobbits down the road in a moment where the Moria orcs (the ‘Northerners’) have left was “four score at least” (TT 63). The Roman maniple, at roughly 120 men was around this size; it had two senior NCOs (non-commissioned officers), centurions, each in charge of half of the unit, but with the front centurion in overall command of the maniple. That might explain the smooth transition of command here, with the junior centurion Uruk taking over naturally when movie!Aragorn slays the senior centurion. For charting the organization, I’ll combine these two, assuming a 120 Uruk company with a senior NCO and a junior NCO beneath him, splitting the company between them.

Combining those accounts, we might sketch an overall structure for the Uruk army. We might imagine a paper strength of 360 for an Uruk battalion, split between 3 Uruk companies of 120 each. That’s not an insane organization – it doesn’t have the problems that the orc army in Return of the King had, with massive solid blocks of evidently many thousands of orcs with no NCOs or organization. I would have liked to see an intermediate regiment or brigade sized organizational layer, since an army with 30 constituent units would be a bit difficult to control (ten sub-units seems to be the normal maximum), but we simply see no hint of this in the film, nor can I detect any trace in the books.

The (not) Drilling Uruk-Hai!

We should next look at the officers – both commissioned and otherwise – to get a sense of how these units of Uruks will be led. But first I think we ought to dig back into the idea of the organizing principle of this army, now that we have a sense of its units.

We can rule out some basic principles. This isn’t a tribal levy or a citizen militia, because the underlying society doesn’t exist. Many of these Uruks (in the film, all of them) were essentially vat grown within the year (Saruman begins assembling his army no earlier than July T.A. 3018, when Gandalf is imprisoned; he is marching out to war in February and March of T.A. 3019). There hasn’t been time for the formation of an Uruk-hai society with horizontal and vertical bonds of loyalty and close-relationships which might sustain that kind of formation. Moreover, if there were, we’d expect the units – rather than being relatively neat and uniform rectangles – to be very rough and irregular, matching the organic patterns of that Uruk society.

Book Note: Peter Jackson seems to have also, at this point, definitively lost track of the large number of Dunlendings (the ‘Wild Men’ of Dunland) who are part of this army. It’s not that they do not exist in the film, because we got scenes establishing them taking (poorly phrased) blood oaths to “die for Saruman.” I think in the casual reading, it is easy for the Dunlendings to fade into the background of the chapter (though a more careful reading shows that Tolkien takes care to update us that the ‘wild men’ along with the largest orcs lead the assault on the gates of the Hornburg, while the lesser orcs and many of the ‘hill men’ are at work against the Deeping Wall). But alas, after that initial oath and some scenes of pillaging, the Dunlendings aren’t seen again in the film. Which is a shame – this is something that a film could do even better than a book: it can express things by putting characters in the background, without having to slow down to explain them. Just have the CGI team work up a few ‘wild men’ models fit for viewing at a long distance (nothing high end) and throw them into the back of the army and the long-shots! Alas, this was not done, removing a level of organizational complexity from Saruman’s host.

But had the Dunlendings remained, I think it is safe to say they would be best understood as a tribal levy or citizen militia. The sense we get of them in the film and the books is that they remain organized under their own leaders and chiefs and in the book’s version of the battle, their presence is marked out, suggesting they remained organizationally distinct (probably as an allied or auxiliary force to the main army, with their own parallel command structure). This may explain why, while the Uruks and orcs break and scatter into the forest, the Dunlendings remain cohesive on the field. Consequently they are in a position to surrender (TT, 176-7), rather than scatter and blindly rout into the magical death forest.

More difficult to assess are the ‘common’ orc-folk of Saruman’s host. It seems likely their number was first drawn from the orcs of the Misty Mountains and Moria, since Gandalf remarks that at their first gathering Saruman was “in rivalry of Sauron and not in his service yet” (FotR, 312). Yet at least some of the Northern orcs clearly considered themselves in service of Sauron, as we see with the Northerners that join with Merry and Pippin’s captors (TT, 56ff). That the ‘fighting Uruk-hai’ are something quite distinct from these, and their intense loyalty to Saruman particularly is made clear in that chapter.

This is thin stuff to make a guess at all of the particulars – we are told less in the books than we could see in the films – but I think the reasonable conjecture (and the one generally arrived upon) is that Saruman had both orcs drawn from the Misty Mountains, as well as Uruk-hai of his own creation, rather different from the Uruks of Mordor. Saruman’s Uruks would thus be bound to him, but otherwise just as deracinated as the Uruks of the film. His Misty Mountain Orcs might well have inherent systems of cohesion – systems of warlordship or tribal cohesion – but those seem likely to be deeply undermined by the raw contempt (and frequent violence) that Saruman’s elite ‘fighting Uruk-hai’ treat them with. This is a familiar feature of real armies: auxiliaries which fight well under their own leaders often fight poorly when bolted on to other armies as explicitly subordinate elements, because the very subordination degrades their cohesive element. It is just very hard to get deeply invested in fighting and possibly dying for people who treat you like garbage that doesn’t matter.

Consequently, I think Saruman’s host in the books – while much more organizationally complex – is likely to have many of the same problems as the movie!host. To spoil my analysis a bit: it has a deracinated, ‘professional’ core that simply hasn’t existed long enough to be properly drilled and isn’t thoroughly officered enough. While at the same time it also has two less professional but potentially more cohesive entities – a Dunlending tribal levy and a Misty-Mountain orcish militia – bolted on; the later of which likely has its own cohesion fatally undermined by the brutal subordination at the hands of the Uruk-hai. Meanwhile, the Dunlending tribal levy is both clearly insufficient to win on its own, but also tactically and operationally subordinated to the Uruks, who may well be the weakest actual element here, despite appearing strong on paper.

So what we have in the Uruk-hai is more nearly analogous to a professional army. These fellows – being effectively vat grown – have no society to be pulled out of, but they are rootless all the same, thrust into a completely new social order, marked out as separate from civilian life. Now, professional armies have all sorts of advantages: they can be kept in the field year-round and long-term because they have no civilian jobs to return to, they can be trained in far more complex things because you have them all of that time and they can, through training and discipline, develop a very strong internal cohesion. These are some serious advantages. But all of that takes time and direction. Unlike levy or militia forces, the cohesion and effectiveness does not rise naturally out of the underlying society. It has to be built.

And it is virtually impossible that Saruman has had the time to do any of this. We can see in the films that the construction of Saruman’s army is not yet begun when Gandalf arrives looking for counsel in The Fellowship of the Ring. The books let us nail down this time-frame as well (since it does seem, from Gandalf’s account, that there was no great orc host in Isengard when he arrived, but only began to be assembled while he was imprisoned there). Gandalf is imprisoned on July 10th, 3018 and escapes on September 18th of the same year, having seen the first stages of the creation of Saruman’s host (but evidently only the very first stages – the creation of furnaces for weapons and such). Saruman’s force must effectively by ‘ready’ by late February in 3019.

One thing I want to note is the conflation of ‘marching in good order’ with ‘effectively drilled infantry.’ It’s a neat visual shorthand, but troops can be made to march in good order long before they can be made to pull off effective pike-unit-tactics on a battlefield. Many a ‘parade force’ has failed on the battlefield because they were over-prepared for the parade-ground. So I wouldn’t read too deeply into the Uruk’s neat formations (especially because they collapse the moment the fighting starts, a fine sign of parade-ground training).

Given the film’s sequence, that gives Saruman about six months to breed, organize, train, equip and then marshal his 10,000 Uruks. The book timeline is a bit more permissive because Saruman’s force is not all these new Uruk-hai, but this is still a mighty fast turn-around. Now, raising a good militia can be done faster than this (because you are relying on existing social structures), as can raising a legion of veterans, or even filling out a unit of hardy old-soldiers with new recruits. But building a professional army from scratch cannot be done at this speed.

In contrast, Gaius Marius – raising one of Rome’s first (semi-)professional armies spent almost two full years preparing his men to fight a serious enemy when he was given command against the Cimbri and the Teutones in 104 B.C. Marius – for complicated reasons best not dealt with here – had broken with Roman tradition and raised his army from Rome’s poor, rather than the landed fellows who generally made up Rome’s citizen-militia army. Consequently, he has much the same problem Saruman does: building cohesion for effectively professional soldiers from scratch (note that later Roman commanders who raise legions much quicker have the veterans of previous post-Marian armies to rely on. Pompey can raise his armies out of old Sullans, and Caesar out of old Pompeians, and Antony and Octavian out of old Caesarians and so on). Marius wins the consulship and command against the Cimbri and the Teutones – invading forces of Germanic/Gallic peoples – in the election of 105 B.C. (for the consulship of 104), then spends all of 104 and all of 103 seasoning his army with small engagements (including just camping – a fortified camp, mind you – near enemies without giving battle) and lots and lots of drill, before feeling ready to risk major engagements in 102 and 101 (where his army thrashes the Cimbri and Teutones quite soundly). And Marius actually does have a core of veterans to use to train this army; even then, that’s two years to build a quality professional force from scratch.

In a real sense, Saruman is attempting to do even more than what Marius needs to do. Saruman actually has to manufacture not only his weapons, but also many of his troops, whereas Marius could find arma virumque (“weapons and a man” for those not enamored of Aeneid puns) readily available for purchase in the Italian countryside. And he is trying to do it in a quarter of the time. Now scratch forces like Saruman’s might be brought up to fighting fit faster by being ‘blooded’ in combat (the United States, in the ACW and WWI sometimes used jumbo-sized units this way, assuming that building effectiveness through experience would attrition those units down to normal strength), but the – relatively small – battle at the Ford on February the 25th is hardly enough campaigning experience for the purpose (of course the fighting on the Anduin doesn’t count because that entire force was lost before it returned, it’s experience and lessons-learned lost underneath the hoofs of the Rohirrim).

So we are left to conclude that – for all of their ferociousness, size and bravery – Saruman’s elite Uruk-hai are actually a very green fighting force; about as green as a granny-smith apple. That’s not necessarily fatal, but it imposes a lot more burden on any inherent cohesive elements (which we have seen are likely lacking) or on the leadership of the force. So what does our officer situation look like?

Major Lurtz, Captain Uglúk?

Not good, it turns out. As we discussed above, it looks like the roughly 120 unit company had a senior NCO (named Lurtz in the film), and a junior NCO Uglúk, a lot like a Roman maniple (but with quite a bit missing, as we’ll see). We don’t see any other leadership structure in the formation, and we get a good enough look at them that, if they had insignias, or other subalterns, we’d probably see them.

Book Note: The books offer both a bit more complexity in some places and a bit less in others. Uglúk now appears as the sole commander of the unit (Lurtz being a movie-exclusive character), but he gives orders which make me think there is a bit more complexity to his command structure, though it is important to remember that through the chapter “The Uruk-Hai” we are dealing with three separate units, Uglúk’s Uruk-Hai, Grishnákh’s smaller group of Mordor orcs and then a number of ‘notherners,’ meaning orcs out of Moria and the Misty Mountains who came down for revenge on the Fellowship (TT, 57); it’s hard to tell at points who is in which particular unit, making it hard to chart a command structure (for as much as the motley group has one). Snaga may be the leader of the scouts (TT, 64). Uglúk also gives particular orders to Lugdush, but he tells him to “get two others” to stand watch over the Hobbits, which implies to me that Lugdush doesn’t command some permanent group, or else Uglúk would have told him “have your squad (or whatever unit) stand guard” instead of simply deputizing Lugdush to grab any two fellows. But it is possible Lugdush is some sort of adjutant.

Above these companies we have the c. 360 Uruk battalion sized units; these almost certainly ought to have a commander, though we don’t see any supernumeraries standing out from the main blocks during the parade (where we might expect to see senior officers). And while there are flags and banners, the lack of consistent placing and spacing makes it hard to judge what kind of commands they represent; it almost looks like there might be about three of them per Uruk-block, which would just imply the 120-Uruk companies we already have. I think we should at least assume Uruk battalion commanders though, since we see that division clearly.

It ends up falling into a standard movie trope, where “general raises his hand” means “attack” and “retreat” and “cavalry” and “arrows” because no one gives or relays verbal orders.

Finally, we have this fellow, who screams and points with his sword, who appears to be the overall field commander, since Saruman does not accompany his army (a risky decision, given how light the organization here is and just how darn green-as-fresh-iceberg-lettuce they are). Notably, he doesn’t appear to have any staff or entourage (unlike Théoden, whose household knights clearly also double as unit commanders or staff officers when necessary). Finally, we have the regular orcs who remain at Isengard, the Dunlendings who vanish from the film and the Uruk ‘berserkers’ (the unarmored, painted fellows who detonate the bomb), who may be an elite unit under separate command. It’s not clear where any of them fit in the organizational chart, except that it seems likely that the non-Uruks are probably not under Uruk command. Here’s a speculative organization chart, with a focus on picking out the officers (commissioned or otherwise; it’s not clear how much meaning the distinction has in this context) in the chain of a single battalion.

How does that stack up to historical comparison? Poorly, it turns out. Even compared to the structure of ancient professional armies (we’ll get to modern forces in a moment) we’re missing quite a lot of officers; in particular, we’re missing the more junior non-commissioned officers (NCOs) and the more senior commissioned officers. Let’s take the Roman army (in particular, the early cohortal legion of the Late Republic) as an initial point of comparison. We can start with the century, a body of sixty to eighty men (depending on the period) commanded by a centurion – the most important type of officer (effectively a senior NCO) in the Roman army. While we have a centurion equivalent in the Uruks (the company commanders and XOs), there is no equivalent to the other, more junior, Roman NCO, the decanus. Decani seem to have been mostly organizational; they led the 6-to-8-man contubernium (‘tent-group’), which shared a tent, cooking supplies, tools, etc; there were ten of these to a century. That said, I am practically certain that the contubernium was also the unit of the file (we are not told this), so the decani would also be the most experienced men in the file and probably had a role in maintaining cohesion. But they probably also absorbed quite a lot of the organizational duties which would have otherwise fell to the centurions.

(Long Aside: I should note that our sources for the period of the Republic do not mention the decani, who begin to appear as our evidence improves in the imperial period, but I think it very likely that this position existed before, if only because it preserves an particular oddity along with the (very much attested) centurions. The decanus (lit: leader of ten) actually leads six or eight, just as the centurion (lit: ‘leader of a hundred’) leads a century (lit: ‘group of a hundred’) of sixty to eighty men men (originally 60 heavy infantry with 20 attached light infantry velites, Plb. 6.24.2-5). It seems very likely that both sets of counter-intuitive names must date from the same period, when the notional strength of a century fit its actual size. Supporting this, the unit that a decanus was in charge of – the contubernium, or ‘tent group’ is attested for the Republic (e.g. Cic. Lig. 7.21) and it is hard to imagine that no one was in charge of the tent and supplies. If that evidence seems like weak gruel, well, that is the normal state of such for the Republican Roman army – if what we still have left of Polybius or Livy doesn’t tell us, we typically don’t know. Alas the organization of the legion prior to c. 210 BCE is – pace Connolly and his valiant effort in Greece and Rome at War – unrecoverable, so we have no way of looking back to that period to try to reason from some ‘pristine’ form. Instead, we tend to work from Polybius’ c. 216 ‘ideal’ legion description and Caesar’s legions in Gaul.)

Moving up the chain, each centurion also had a junior NCO under him (but above the decani of his century), the optio, who stood at the back of the century in battle. Each century had its centurion, the optio as well as a standard-bearer (the signifer). Originally, the key tactical unit had been two centuries together, the maniple, which was commanded by the senior of the two centurions (whose maniple formed in the front). This would map neatly on to our Uruk company (both being 120 men); for comparison where as the Uruk company has only 2 NCOs, the Roman maniple has 26, 2 centurions, 2 optiones, 2 signiferi, 20 decani! That said, while the maniple remained an organizational unit in the late Republic, the key tactical unit had become the cohort, which was three maniples together (six centuries) commanded by the lead centurion of the first century of the cohort, the pilus prior.

So in terms of officers, a cohort of Roman infantry (with about 480 fighting men) would have 6 centurions, 6 optiones, 6 signiferi and 60 decani. That is quite a lot more officer (all more-or-less non-commissioned in the Roman case) than the Uruk’s seven for a unit of 360. Also missing from the picture is overall army command (we’re jumping to the top level) – a Roman army would have a magistrate (typically a consul) leading a force of two legions; each legion had six military tribunes assigned to it. Senior military tribunes in this period had a minimum of ten years service, junior military tribunes five (Plb. 6.19.1-2), so while on occasion military tribunes might be somewhat fresh-faced aristocrats, most of them were serious and experienced soldiers who knew how things ought to function. While the Uruk-What-Points-Swords-At-Things could be the consul-equivalent (two legions being roughly 10,000 men), he is missing his dozen military tribunes to help him manage logistics and operations and even occasionally act as independent commanders when some force needed to be broken off to go do something.

And while Roman military organization was, overall, uncommonly good, they were by no means the standouts in terms of having a lot of officers and NCOs. Hellenistic armies (post-Alexander Macedonians) were evenly more heavily stratified. The syntagma of c. 256 was broken into 16 files of 16, with each file having (in order of seniority), a file leader (the lochagos), file closer (ouragos), 1 half-file leaders (hemilochites), and two quarter-file leaders (enomotarchs). It didn’t stop there, the full command structure of a syntagma, was 1 syntagmatarch, 1 taxiarch, 2 tetrarchs, 4 dilochites, 8 lochagoi, 16 ouragoi, 16 hemilochites and 32 enomotarchs, with five more supernumeraries (adjutant, rear commander, herald, flag-bearer, trumpeter). That’s 85 officers, NCOs and supernumeraries for a unit of 256, smaller than our 360 Uruk battalion.

This is, admittedly, one of the most complicated organizational systems I know of for a pre-modern army, and one wonders the degree to which Asclepiodotus has embellished the system (as writers of military manuals are wont), but in the broad outlines, we see good evidence that this was, more or less, the system in use.

And those are ancient forces. Compared to a modern force, Saruman’s array is honestly pathetic. A modern infantry battalion with a strength around 650 or so (allowing for significance variance service-to-service and country-to-country) ought to have something like 1 Lt. Col, about a half-dozen Majors and Captains each once the HQ is accounted for, a couple dozen lieutenants and a slew of NCOs besides (honestly, NCOs are massively important for the function of any modern military unit). And that is before we count any special elements within the battalion that might be directly attached to the battalion HQ. Modern warfare is really complex and requires a lot of coordination, in no small part because it simply isn’t possible to keep a unit concentrated in the face of modern firepower and the more you spread out (to conceal and use cover and just generally keep everyone from being hit by any one bomb) the more sub-commanders and sub-sub-commanders and sub-sub-sub-commanders you need.

Now, you may ask why we have gone through all of this, and it is because I think it is going to be useful for informing some of the tactical failures that we’ll see from Saruman’s Uruk host. Having all of these officers (commissioned vs. non-commissioned being a less useful distinction in the ancient world), as our ancient examples do, enables them to be more tactically flexible and organizationally complex. If all you need to do is get your army to attack forward, you do not need these complex systems of officers and sub-officers, and sub-sub-officers. Indeed, Greek hoplite armies have very few officers (with the Spartans being a notable exception) and did just fine in simple single battles; but they were notably quite rubbish in sieges and fortress assaults, which is the mission this army is on. Asking a hoplite army to do complex maneuvers was also a recipe for disappointment. If you want to be able to engage in complex maneuvers (first platoon demonstrates on the left, second platoon establishes a base of fire in the middle, third platoon goes around that hill over there and takes them from behind), or handle many different tasks at once during a siege (to dig some trenches, while also manning some catapults, while also standing guard, while also building a ramp, while also tunneling under the walls…), distributing command like this is essential.

This isn’t a straight 1-to-1 comparison, I should note. An army’s capability to handle complexity does not scale evenly with the number of officers; experience, organizational culture, training and individual initiative all play a role. Generally Roman armies, while having somewhat fewer officers, tended to be more tactically and organizationally capable than Hellenistic armies (I suspect this has to do with the greater frequency of Roman wars and thus the higher average level of actual campaign experience, but that’s an argument for another day). But by and large, more officers tends to indicate an army capable of more tactical complexity. This is a major problem for Saruman. Storming the defenses at the Isen was not a particularly complex operation, especially given the overwhelming numerical superiority his force possessed and the relatively weak defenses there. But assaults on fortress-complexes (like the one at Helm’s Gate) generally are very complex, requiring a lot of tasks to be happening in parallel in order to success. And Saruman’s army just isn’t well organized for that.

Conclusion: The Greenest Orcs

And now we circle back to cohesion. Keeping an army together when everyone is safe and everything is going right is difficult, but not impossibly so. But you need strong bonds to keep folks in the line, doing their jobs, when they are under fire or when things are going very wrong (and things always go very wrong in war; ‘everything went just to plan’ is a phrase uttered honestly by no commander anywhere ever).

But of course the other desperate problem that Saruman has is that he needs these officers to also supply cohesion, because – as noted above – he cannot rely on long-established social structures or experience to do that for him. And there are just not enough officers here. Which would be fine if he could rely on long experience, training and drill to hold the army together under stress, but these fellows are greener than the spring leaves. Which might be salvageable if Saruman could rely on deep social systems of cohesion based in long-standing traditions of social organization, but he grew this army in a vat last week.

In short: this is an army with organization is poorly suited to the underlying social conditions of Uruk society (or the lack thereof), which hasn’t been given anywhere near the necessary time to forge a new, deracinated professional society to replace it. Consequently, this army performs poorly exactly as we might expect: it disperses when it needed to concentrate, fails to scout effectively, fails to intercept key enemy forces, launches a disorganized, under-cooked assault on a fortress and in the end fails to defeat a largely non-professional (but highly motivated, highly cohesive) force a fraction of its size. The sins of the training field bloom on the battlefield.

To be clear: I don’t think this is a failing of either Tolkien or Jackson! This kind of miscalculation happens all the time and it is not surprising that Saruman – arrogant and overconfident – makes this very mistake. This may seem like a problem that only exists in silly internet analyses of fantasy armies, but this is actually a very real, real world problem. Again and again, we’ve seen efforts to apply modern ‘western’ military systems outside of modern industrialized countries (which have large, already deracinated urban populations tailor-made for this kind of army) just fall apart because that military system wasn’t indigenous to those people and it was very poorly suited to their social and cultural conditions. Likewise, we’ve seen (fewer times, but still fairly frequently) leaders in desperate situations try to call upon some sort of primordial tribal or citizen levy, only to find out that it doesn’t work, usually because they themselves spent the previous decades dismantling the systems which sustained those levies (typically because those systems represented competing centers of power in the society).

But this is exactly the sort of mistake I’d expect to see from the man with a mind of “gears and wheels” who fails to take the human element – or in this case, the orcish element – into account. I am sure in Saruman’s immaculate planning document (which I have no doubt exists and probably have an accompanying powerpoint), his Uruk army looked very impressive. Well-equipped (for the wrong battle, but we’ll get there) and nothing like the ‘rabble’ of Rohan’s barely-armed peasants it was facing. A modern army. I can almost hear the modern version of Saruman bragging about the expensive jet-fighters and refurbished Soviet tanks they just purchased. Except he didn’t leave himself time to train any modern orcs, and so he created a paper tiger (or paper-Mûmakil?) that is going to fall apart the moment things begin to go wrong and its cohesion is properly tested.

I’ve noted elsewhere on this blog that all armies replicate peacetime social systems on the battlefield. We can now add a correlate to that: armies that do not, generally fail, both in suppressing those cultural norms, but also in the test of battlefield effectiveness. Attempting to apply a foreign military ‘package’ can work, but only if that set of technologies, organization and practices can be locked into existing social structures. Building a professional tradition from scratch, by contrast, takes years – when it is possible at all. It can be done – but often only by radically transforming the underlying society to fit the new military system; the more common outcome is an army with a foreign veneer that never quite functions properly – and often performs quite a bit worse than forces with indigenous organization.

Next week, we will look at a far more socially embedded, complex hybrid army with the Men of Rohan and see how different social structures can generate different kinds of cohesion to create an effective fighting force.

given the large caverns underneath isengard, it is possible that at least some of the infrastructure actually was built before the confrontation with Gandalf (and this is heavily suggest in the books, given that we have part orc men in saruman’s service, both half-orc men in the army and individuals like the “squint eyed southerner” encountered spying at Bree. (which tolkien’s letters identify as being a spy of Saruman) these adult part-orcs indicate a substantial pre-existing eugenics program in place. indeed the book lacks the entire “underground pod” aspect and indicates that the Uruk-Hai were bred from common orc stock, with at least some human interbreeding involved as well. this sort of program would require decades at minimum to pull off. We know that his human servants were present when Gandalf confronted him, so it would seem likely he’d been working on his army in secret for soem time, in much the same that he had been working on recreating rings of power. (which we know he had put into practice as well, giving himself the name “ring-maker” and wearing a rather prominent ring when gandalf confronts him)

and it is not known by how much the uruk-hai were actually bred for their role, as the detachment that captured merry and pippin refer to training as being part of the reason they can tolerate sunlight and run for such long distances.

“‘But what are we going to do at sunrise?’ said some of the Northerners.

‘Go on running,’ said Uglúk. ‘What do you think? Sit on the grass and wait for the Whiteskins to join the picnic?’

‘But we can’t run in the sunlight.’

‘You’ll run with me behind you,’ said Uglúk. ‘Run! Or you’ll never see your beloved holes again. By the White Hand! What’s the use of sending out mountain-maggots on a trip, only half trained. Run, curse you! Run while night lasts!'”

this suggests that even normal orcs can be trained to achieve endurance and sun tolerance similar to the uruk-hai. which may mean that the Uruk-hai were not a specific breed of orc so much as just an elite force drawn from the biggest and toughest of the mountain tribes, then given special training. Ugluk’s boast certainly implies such a state:

‘We are the fighting Uruk-hai! We slew the great warrior. We took the prisoners. We are the servants of Saruman the Wise, the White Hand: the Hand that gives us man’s-flesh to eat. We came out of Isengard, and led you here, and we shall lead you back by the way we choose. I am Uglúk. I have spoken.’

this is a boast of elite unit status, not really that of racial status. it may well be a bit of both specially bred orcs and recruits, with the core of the force being the results of Saruman’s breeding programs, and then bolstered by recruitment of any mountain orcs which can meet the physical requirements of the training. (with very likely those that pass the training going on to participate in the breeding program.)

it is also clear that in the books at least, the Uruk-hai’s main advantage over normal orcs was their superior gear:

“There were four goblin-soldiers of greater stature, swart, slant-eyed, with thick legs and large hands. They were armed with short broad-bladed swords, not with the curved scimitars usual with Orcs: and they had bows of yew, in length and shape like the bows of Men. Upon their shields they bore a strange device: a small white hand in the centre of a black field; on the front of their iron helms was set an S-rune, wrought of some white metal.”

weapons similar to that of human armies, and likely rather greater than usual quality than the typical orc gear. indeed the description sounds rather like an attempt at roman gear. especially the “short broad bladed swords”, which sound very much like a gladus, it would not be terribly hard to imagine them being armed equivalent to the roman Principes from the republican legions.. gladius and large shield, possibly with throwing spears, as we are told that the orcs at helms deep “waved spears and shields” during the initial assault.

however it is also clear that the uruk-hai army is not as highly trained or skilled as a roman army would be, or as ugluk’s boasting tried to imply.during the assault they make little effort to use elaborate strategy, instead appearing to rely on sheer numbers and brute strength to win the day.

so even in the book it is likely that the organizational and ‘cultural’ issues seen in the film were still present. the uruk-hai, whatever their origins, were clearly a separate force from the mountain tribes, even though such tribes would have been part of saruman’s whole program. even if the uruk’s had begun as recruits from the orc tribes their training as uruk-hai broke those ties.

this makes an interesting dynamic relative to the film depiction. in the film the uruks are at least basically organized as a fighting force, yet their equipment for all its standardization and nominal quality was not much different than the orc equipment seen in the mountain tribes. cutting type swords, shields that can double as stabbing weapons, spears. just standardized and made more durable than the usual. they use basic strategy and tactics and fight as organized units. they are just a paper tiger.

while in the books the uruks are equipped as like a human army, yet are clearly still fighting like that of a tribal orc army, with little strategy and only the most basic tactics.

I have the book with me. In addition to the Uruk-Hai being of greater stature than the other orcs(which you quote), the appendices make it clear that they’re another race of orcs altogether, “Related [to the word orc], no doubt, was the word Uruk of the Black Speech, although this was applied as a rule only to the great soldier-orcs that at this time issued from Mordor and Isengard. The lesser kinds were called, especially by the Uruk-Hai, Snaga “slave”.” This is from “Of Other Races” under Appendix F of the full Lord of the Rings book, which I imagine is included in separated editions as part of Return of the King.

So the Snaga on TT page 64 is not the leader of the scouts necessarily, Snaga or “Slave” is what the Uruk-Hai are calling him, a non-Uruk. It’s not just their equipment that makes them different, they are taller than the other orcs, are bred specifically for combat, and are downright contemptuous of regular orcs.

Thematus: Uruk-hai is not a term specifically referring to the orcs which Saruman bred; it simple means ‘the orcs’ in the sense of that people. The previous discussion here is essentially correct though; the orc and half-orcs in Saruman’s army must have taken a long time to breed, as they were produced by causing Men and Orcs to mate and produce offspring over, it is implied multiple generations (History of Middle Earth Vol 10, “Myths Transformed”, section X). Therefore to breed them must have taken some time, decades at the minimum. We know that Saruman had become evil and planned to sieze the Ring at the latest by the time of the meeting of the White Council in 2851, over 150 years before the events of the War of the Ring (LotR, Appendix B). So there is nothing in the books to support the idea that the majority of Saruman’s army were young and undrilled.

It is important to note that the idea of finding orcs buried under the ground, fully adult, in plastic bags has no origin in the books. Such a thing would have been anathema to Tolkien the devout Christian, who in the above quoted section of HoME X and in several of the published letter, particularly Letter 153 wrestled with the theological implications of orcs. He considered the fact that they were rational, incarnate beings indicated that they had souls, and therefore could not have been created by any Ainu; they must have been derived from Elves and or Men or Maiar. Tolkien was very clear that only God can create life.

@Elizabeth Watts – read the part in the appendix that I quoted, it’s quite explicit that Uruk-hai is used to refer to the soldier orcs, even though the term itself *literally* applies to all orc-folk, *in practice* it doesn’t at all. The same goes for the Olog-hai, the super-trolls that walk in the sunlight. All in the Appendices to Lord of the Rings. Take a look at it, I quoted it verbatim in my previous post.

I believe that the Silmarillion implies that the Orcs were once Elves that Morgoth had twisted and transformed; this implication is made explicit in the movie where Saruman talks to Lurtz (“Do you know what Orcs are? They were once Elves…”) but that J. R. R. Tolkien himself was unhappy and apparently wanted to change their origin, but couldn’t get around to doing so. I don’t have a reference in his letters, so what you’ve cited in HoME essentially holds.

I can buy Saruman having turned essentially evil 150 years prior to the events of LotR and having had dealings with Sauron and with different Orc-tribes, and building up Isengard, but I can’t buy him having spent all that time in Isengard building an army of Uruk-hai, training them and cross-breeding them without either the people of Rohan or the other Wizards discovering the Army. Saruman would have to be hiding that treachery in plain sight, and he could pull that off with his industrial machinery, but hiding an army of Uruk-hai as if they were mice…not even a Wizard can pull that off for 150 years!

I think you’re both right. It always seemed self-evident to me that the “-hai” suffix in uruk-hai and olog-hai meant something akin to “elite” or “über”. Thus, “uruk” would simply be the orcish word for orcs, and would apply to all orcs, but “uruk-hai” were super-orcs, whether in the service of Saruman or Sauron.

The hai element does not mean either “super” or “uber.” It is merely the word for “people,” thus “orc-people” and “Drú-people” (the orkish name for the Drúedain).

@ Ed8r: I stand corrected, then.

There are historical examples of the term for “people” being the same as the term for “army”, the army being conceived as the people-in-arms. E.g., the Latin word “populus” seems to have originally meant “army” (cf. “populari” = “to devastate a territory with one’s army”). So it’s possible that a similar development has happened/is the process of happening with Orcish, with “-hai” meaning both the people in general but also the soldiers specifically.

Another possibility is that non-orcs tended to encounter the term “Uruk-hai” in a military context and consequently applied it to the (elite) orcish soldiery rather than the orcs in general. So in Orcish itself, “Uruk-hai” just means “Orc-people”, but in Westron it means “elite orcs”.

In support of this latter interpretation, I think the term is only used for Saruman’s — relatively large and powerful — orcs in LOTR? I think the rest are generally just called orcs. And of course, there are also historical examples of this sort of thing happening. (Cf. “sombrero”.)

Appendix F of LOTR says “that [Uruk] was applied as a rule only to the great soldier-orcs that at this time issued from both Morder and Isengard (note that Mordor is mentioned first).

I confused the spelling of a couple terms, however: The Drúedain were called Oghor-hai. The Olog-hai were indeed Sauron’s new race of trolls.

Ed8r is on the right track, they are distinct sub-species, originating from Mordor. Another reference to this is Appendix A “In the last years of Denethor I the race of Uruks, black orcs of great strength, first appeared out of Mordor, and in 2475 they swept across Ithilien and took Osgiliath.”

That’s over 500 years before the events of LOTR. In The Choices of Master Samwise, Shagrat (a Mordor orc) refers to the soldiery as “Uruks”. There is a further reference to the term “Uruk-Hai” that indicates it’s not unique to Isengard: Frodo and Sam, after escaping from Cirith Ungol, hide from two orcs scouting. One is a large, soldiery type who makes mention of a hypothetical “pack of rogue Uruk-Hai” – he’s clearly talking about Mordor orcs, not Isengarders.

My take on it has always been that Uruks are greater orcs bred by Mordor for more efficient soldiery, but then used by Saruman to create his own Uruk version by adding human blood also. It’s notable that Grishnakh of the Mordor orcs that form part of the party that capture Merry and Pippin is bowed and long-armed, but still large and powerful, and there is no mention of his Mordor orc contingent having trouble in the sunlight, unlike the smaller Northerners. Whereas the Isengarders are upright and bluntly described as physically distinct.

To me, it’s a no-brainer that Saruman’s been at it for decades, with Bill Fearny’s mate at Bree at one end of the spectrum and Ugluk’s crew at the other. As for how he created the army, as someone else said – he did the decades of breeding and experimenting in some hole in the encircling mountains. He’s not going to risk showing his hand to Lothlorien or Rivendell, particularly when he’s still hunting the Ring.

As a final note, I think, when Gandalf did his final visit to Saruman, was imprisoned and learned of the treachery, he simply didn’t see when he arrived what had happened to Isengard in those final days (the vale of Isengard isn’t small), until he was trapped on vantage point of the top of Orthanc. The phrasing he uses when describing it implies it heavily to me.

Would Saruman necessarily have had to build his army in Isengard itself? The Misty Mountains are right next door, so Saruman could have established his breeding/training centres somewhere towards the southern end of the range, close enough to keep an eye on but still far enough that the connection between the two places wouldn’t be obvious. And given that the Misty Mountains are crawling with orcs anyway, his army-building programme might well have gone unnoticed by outside observers.

That is a very good point. Clearly if he had been doing this openly, the fact that Orthanc was filled with pits and forges, and that wolves and orcs were housed there would not have come as a surprise to book-Gandalf when he arrived there and was captured . On the other hand, we do know that Saruman had many underground places and many rooms dug out of the Circle of Orthanc, so he might have run his breeding programme in there for a time, undetected.

I’d also point out that Saruman was skilled in persuasion (and presumably deception). I think Gandalf was only able to see what was really going on at Isengard after his imprisonment because “the scales had fallen from his eyes” and that Saruman no longer felt he needed to hide his activities. (Also, maybe that vantage point thingie mentioned above.)

The uruk-hai also seem better organized/drilled in basic tactics – in the fight against the Moria orcs, Boromir successfully single-handedly drove them off because they seemingly had no coordinated tactics, while when the uruk-hai joined they defeated him by using Archer support well, not just by being bigger and stronger.

Great analysis, as always. I have the impression that the “mind of wheels and metal” Saruman tried to compensate for the lack of time available to him in true STEM supremacist fashion, using his “foul craft” to pre-program his Uruk-Hai with battle skills, especially so in the movies where we see the breakneck speed at which Saruman is creating them. Rather than having a culture, they’re biological robots, or effectively the sentient equivalent of soldier ants. Lurtz strangles one of his orc “manufacturers” the moment he’s born and then swears loyalty to Saruman, suggesting that Saruman already had them programmed to be soldiers off the bat rather than bothering to teach them.

The funny thing is that these Uruk-Hai, if preprogrammed, are the LotR equivalent of the B-1 battle droids who are pretty much built for war and sent out to fight (we see that in Attack of the Clones)- and we see Christopher Lee as Count Dooku creating a whole lot of those on Geonosis! And then they’re all turned to scrap metal by the attacking clone army, who, despite being vat grown like the Uruk-Hai, have been trained and organized for years…whether he’s playing a Fallen Wizard or a Sith Lord, Christopher Lee manufactures an untrained army in both movies and lands up getting his forces wrecked!

One possible factor here, at least in the books, is that Saruman (see Gandalf’s account of how he met Gandalf with a ring on his finger in ‘The Council of Elrond’) has apparently been engaging in ring-forging. It may be that Saruman is able to exert some kind of personal control or guidance over his forces (even remotely.) I think in the chapter ‘The Riders of Rohan’ when Aragorn and company are chasing the orcs, one of the trio comments that there is some power which lends the orcs speed, and sets its will against the trio.

Saruman’s plans for the Battle of Helm’s Deep might include a quiet evening ‘in’, smoking his pipe and staring intently into the Palantir of Orthanc, as he remotely directs or influences the battle – and then the ents show up and start to kick his front gates down.

Of course, the ring would need to convey information back to make the control more than trivial.

Saruman had a palantír until after being defeated, so he gets all the information he can require that way.

Typo:

We can see in the films that the construction of Saruman’s army is not yet begun when Gandalf arrives looking for consul in The Fellowship of the Ring.

Do you mean “counsel” here?

Fixed!

The organisation of the Hellenistic Syntagma seems *suspiciously* mathematical. It’s the same system you would get if you gave every man a number from 0 to 255 and told them their rank was the position of the last 0 in the binary expansion of their number (with the lowest two ranks merged into one).

That’s the kind of system that I, as a mathematician, would dream up to satisfy my desire for order and neatness. But it’s rare for the most mathematically elegant solution to also be the most practically useful (at least in this kind of situation where there are social factors at work, mathematically neat solutions often do work well in engineering). So I’m worried that the description was fabricated by someone with the same desire for neatness. Was this Asclepiodotus fellow also a mathematician?

Ayep. That was what I meant to imply in the caption. Asclepiodotus is a philosopher, not a military man, so there’s a fair but of suspicion he’s just pulling our leg. That said, we see these leadership titles in our sources. The Lochagoi and Ouragoi, at the very least are very well attested.

On the reliability of it, note G. Wrightson, “To Use or Not To Use: The Practical and Historical Reliability of Asclepiodotus’ Philosophical Tactical Manual” in Ancient Warfare: Introducing Current Research (2015). Wrightson concludes (as does Sekunda, Hatzopoulos and Connolly) that while Asclepiodotus is idealizing for sure, it is broadly usable.

Asclepiodotus is probably faking it. For any given military structure, the number of steps that an order has to go through from the supreme commander to the front-line soldier is log(sub(k))(n), where k is the number of other soldiers that any officer is responsible for, and n is the number of soldiers in the force. Asclepiodotus has set k to 2 or 3 – every node in this tree is responsible for no more than 3 men at a time, which essentially maximizes the saturation of officers within the formation (any less than that and you have officers with one report, which is stupid).

Since an officer can likely command more than 3 people, the search is on to find the right k-value to minimize the number of hops in the structure while not overburdening an officer. The romans seem to have pegged k at a theoretical 10 but in practice at 6-8. Saruman’s k is somewhere from 30 to 60, so Saruman can command a force of 10000 men with only 2-3 hops between supreme commander and front-line combatant. Likely higher k values are more possible in more experienced and co-ordinated armies, so Saruman’s choice is the exact opposite of appropriate – if ever there were an army that _needed_ a k of 2 or 3 to function, it would be this one. That would mean _13 or 14 layers_ of officers between sword-pointer and the fighting Uruk-Hai.

Just a nitpick, but if you’re using modern terms like XO and NCO, then the commanders of company-sized units are “captains” and the leaders of 60-strong platoons are “lieutenants”. NCOs they are not.

In charge of a 360-orc battallion would be the equivalent of a major or lt-col, and there ought to be a 3-battallion unit similar to a regiment, under a (forgive me) orcolonel. Ten of those would make up the whole army, possibly grouped into a few 2- or 3-regiment brigades.

I’d argue that the Uruks do come from “a common society”: they’re essentially cloning-vat brothers, “birthed” and grown together, throughly brainwashed by current-day standards. This, and their orcish ferocity and bloodlust, would create some cohesion in combat, at least until they realize that, contrary to what they’ve been taught, they aren’t invincible.

So, the exact break between COs and NCOs is very much variable from one army culture to the next. Mostly, it is a class distinction – when does ‘commoner promoted through the ranks’ end and ‘petty aristocrat given command by right of birth’ begin. Thus the centurion primus pilus of a legion is generally treated as a ‘senior NCO’ despite being the XO of a unit of **5,000**. The Uruk officers are vat-grown, just like the rest and have no real difference in insignia, equipment, background or status. So I treated them as NCOs.

But then there are armies that don’t even have this neat class distinction. In the IDF, every combat soldier is recruited as a private – officers are trained exclusively through an officer candidate school for sergeants, rather than separately as at American staff colleges. (In non-combat roles this is mostly the same, but warrant officers have a specific stream called Atuda in which they go to uni before military service rather than after and are then obligated to serve in their field of study, e.g. engineers and doctors.)

Allowing that, essentially, the difference between officer and NCO is that officers receive advanced command training and education, it would follow that Saruman’s army has exactly one officer – Saruman himself, and he’s staying far behind, leaving his First Sergeant in charge while he’s busy looking through his Palantir or something. All the others (including the screaming general) are promoted from the ranks and there simply wouldn’t be enough time to put them through Isengard War College.

Then again, not even Saruman seems to have actual officer training, so it could be argued that Saruman’s force has no officers at all. I’d say this is exactly the kind of conceptual mistake likely to be made by an ivory-tower savant trying his hand at army-building from scratch. Without experience managing sentient beings (regardless of species) it’s easy to overlook friction until it bites you in the soft parts.

Allowing that, essentially, the difference between officer and NCO is that officers receive advanced command training and education,

I think that’s too narrow a definition, as the commissioned officer/NCO distinction long predates the development of formal staff colleges and officer training system. A better question, I think, would be “Is this position usually filled by someone who entered the army in a command position, or who started as an ordinary soldier and was raised from the ranks?”

Yes, a distinction which is in turn almost invariably coupled with a social-class distinction. NCOs are typically commoners who rise through the ranks, whereas commissioned officers are typically drawn from the elite, or at least the gentry. In society after society, you find that distinction replicated because – again – societies recreate their social order on the battlefield.

But then Israel is not a particularly egalitarian society, and it wasn’t even that egalitarian in the 1940s when the IDF command structure was put into place. The social elite in Israel would be recruited into elite units, like the Air Force or commando units (sayarót, sg. sayéret); they’d operate separately rather than boss the Yemeni immigrants around, and while pilots get officer ranks, sayeret members do not and are discharged with the usual ranks of combat troops with 3 years’ experience (usually sergeant).

The usual explanation I’ve read in popular sources for the IDF rank structure is that it comes from a militia (Haganah) that was turned into a regular army. Elsewhere we similarly see irregular armies blur the officer-enlisted distinction, e.g. the French Resistance didn’t really have ranks, just people put in charge of units of various sizes, and then after liberation the Resistance was integrated into the French army rank structure based on how many troops one had led.

@theoriginalmrx

“the commissioned officer/NCO distinction long predates the development of formal staff colleges and officer training system”

True, but even then, there were skills deemed essential for officers – they just weren’t the sort we’d necessarily appreciate today (e.g. Latin and heraldry instead of logistics and military history). Their officer class learned those skills during their education, just as ours do today.

@Brett Devereux

“NCOs are typically commoners who rise through the ranks, whereas commissioned officers are typically drawn from the elite, or at least the gentry”

Yes, however most, if not all, militaries also had ways to promote successful NCOs to officer positions. Although this promotion would require a certain skillset to be acquired by the candidate, as per the standards of their time and society. Thus, specialized education is a better differentiator between officers and NCO-like ranks, than the person’s social origin.

So I guess you were right after all, orc centurions are indeed NCOs.

@AlexT

I’ve read that about 20% of officers in the British Army during the late 18th/Early 19th Century were promoted from the ranks (I think this was in an afterword to one of Cornell’s Sharpe books, so it may not be reliable). Some armies, for example ancien regime France, required multiple generations of noble ancestry, that is officers must be members of the arms-bearing class. We can see how that did little to improve the officer corps of France’s pre-Revolution army by the number of marshals in Napoleon’s armies that had been NCOs under the ancien regime, although it may have improved its political reliability (not sure about that either: witness Lafayette)

———————————————————————–

Regardless of that, I’m not sure the commissioned/non-commissioned officer distinction is one that’s entirely relevant to a medieval army. There was clearly going to be a hierarchy of command, even if the Uruk-hai were biological robots (a position I don’t think is supportable from the texts), and raised from birth (or age 7) to fulfil all the stereotypes that have become attached to Spartan warriors.

Anyway, this suggests a question for Our Gracious Host: would the Uruk-hai army be something akin to Janissaries? Well, badly trained and under-officered ones.

Well, they were common enough to have a name — rankers — though that also meant gentlemen who enlisted as common soldiers.

> “most, if not all, militaries also had ways to promote successful NCOs to officer positions.”

This is true of many very modern militaries, but was vanishingly rare in early modern armies and functionally impossible in most pre-modern armies where high positions of leadership were restricted to social classes (knight, etc.) which were often strictly hereditary (the knightly class becomes progressively less porous over time, for instance).

There was, for instance, no mechanism in the Roman army for a senior centurion to become a military tribune, legate, praetor or consul. While some *very* senior centurions rarely seemed to have been able to amass the wealth to retire into the equestrian order (in the imperial period), that’s still both 1) super rare and 2) not enough wealth to gain access to the Senate, the prerequisite of army command (admission to the senate required a fortune of 1m HS, compared to 400k HS for the equestrian order). This is often obscured with Plebian generals being misrepresented as ‘commoners’ when they were, in fact, wealthy members of the gentry (e.g. Gaius Marius was almost certainly from a prominent and well-connected family in Arpinum; Plutarch’s claim that his family was common doesn’t stand up to much scrutiny).

So I would be very careful in assuming that most – or even many – militaries had this in any kind of regular function before 1940 or so. Officer Candidate School in the US Army dates back only to 1941, for instance, and the level of class stratification in the US Armed Forces has typically been *lower* than in contemporary European militaries. People in sharply class-stratified societies tend to believe in their class-stratification systems and build organizations on the assumption that the elite class really is better at leading.

Given the obvious bias of the elite literary perspective we have for most periods before the Early Modern, I’m not expecting much, but do we have any evidence concerning to what degree and in what ways non-elites bought into elite leadership / commissioned officers as opposed to non-elite leaders / NCO?

On the one hand, there’s the stratification of wealth, concentration of social ties, and prominence of aristocratic honor / reputation which would give elites a leg up on non-elites in terms of relevant skills and experience in military as well as reason to prosecute their tasks with some vigor. On the other hand, it also seems like such different upbringing might be damaging at least in a long-service professional army with its separate internal structure allowing non-elite soldiers to develop professional identities and more or less become their own power bloc that might, potentially, act without or even in opposition to elite leaders.

@ AlexT:

True, but even then, there were skills deemed essential for officers – they just weren’t the sort we’d necessarily appreciate today (e.g. Latin and heraldry instead of logistics and military history). Their officer class learned those skills during their education, just as ours do today.

Eh, nobles were educated in those things, and being noble was deemed a prerequisite for command, but it would be a real stretch to describe education in heraldry as “command training”.

@ Swamp Yankee:

I’ve read that about 20% of officers in the British Army during the late 18th/Early 19th Century were promoted from the ranks (I think this was in an afterword to one of Cornell’s Sharpe books, so it may not be reliable).

That might be accurate. Bear in mind that during the late 18th/early 19th century the British were engaged in the Napoleonic Wars, and big conflicts like this often lead to a relatively high amount of social mobility as talented people get promoted higher than they would during more normal circumstances.

On a bit of a tangent, I’d just like to do a shout out to Sir William Robertson, (1860-1933), notable for being the only man in the British army to rise from private (well, trooper, since he first enlisted in a cavalry regiment) all the way up to field marshal.

@ Bret:

This is often obscured with Plebian generals being misrepresented as ‘commoners’ when they were, in fact, wealthy members of the gentry (e.g. Gaius Marius was almost certainly from a prominent and well-connected family in Arpinum; Plutarch’s claim that his family was common doesn’t stand up to much scrutiny).

I’ve often thought that the distinction in modern Britain between lords and commoners is a good parallel to that between patricians and plebeians: you have a theoretical upper class, but any meaningful privileges have long since been eroded away to basically nothing, most of the powerful positions are held by members of the notional lower class, and anybody who assumed that lord/patrician = rich and powerful whilst commoner/pleb = poor and oppressed would be badly misunderstand the actual way in which the society was organised.

@ Writing:

At least in the British army, soldiers tended to prefer noble (or at least upper-class) commanders, and to resent officers promoted from the ranks as “jumped-up and no better than us”. Cf. Bret’s point about armies replicating their society’s overall structure (which in Britain was one in which the upper classes held the lion’s share of power) and attempts to go against this generally causing problems.

@theoriginalmrx

I’d posit that heraldry and Latin are very useful skills for the (Latin western European) medieval officer. Before universal uniforms became a thing, the only way to recognize friendly and enemy units at distance is to recognize the sigils and coats of arms on their armor, shields, and banners. Instant recognition of sigils is the only way to avoid friendly fire, properly identify enemy officers, and generally coordinate movements of your own men.

Understanding Latin is also the only way to read the Roman treatises on military strategy/logistics/organization like Vegetius’ De re militari, which have an immense amount of relevant information for conducting a campaign.