This series is now available in audio format. You can find the playlist here.

This is the second part of a four part (I, II, III, IV) look at the Dothraki, the fictional horse-borne nomads of the A Song of Ice and Fire / Game of Thrones series. We’re looking at, in particular, the degree to which George R.R. Martin’s claim that the Dothraki are “an amalgam of a number of steppe and plains cultures” holds up in the face of research. Our last part, “Barbarian Couture” looked at the influences that shaped the visual depiction of the Dothraki and found them badly wanting, more based in stereotypes and misconceptions than historical reality.

This week, we’re turning to the foundation of social structures: patterns of subsistence (which, to be clear, means in plain English: “how do they get food and basic resources?” That’s all subsistence is – how do you get enough resources to survive.) Originally this was going to fit into a larger argument about culture, but I decided to break it out because we are at long last looking at the logistics and subsistence strategies of nomadic peoples. Every time we have covered the logistics of agrarian armies and societies, there has been a request to do a deeper dive into the way that Steppe nomads in particular, and nomads more generally, are different. Well here it is!

As always, if you like what you are reading here, please share it; if you really like it, you can support me on Patreon. And if you want updates whenever a new post appears, you can click below for email updates or follow me on twitter (@BretDevereaux) for updates as to new posts as well as my occasional ancient history, foreign policy or military history musings.

(Bibliography note before we dive in. I am not going to run through everything I’ve glanced at here, but for those looking to read more on this or retrace my steps more generally, a good starting place on the Steppe peoples is T. May, The Mongol Art of War (2007). There’s also more than a dash here of bits from K. Chase, Firearms: A Global History to 1700 (2008) as well as T. Ratchnevsky, Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy, trans. T.N Haining (1991). For the Native Americans of the Great Plains, I have relied principally on A.R. McGinnis, Counting Coup and Cutting Horses: Intertribal Warfare on the Northern Plains, 1738-1889 (1990), F.R. Secoy, Changing Military Patterns of the Great Plains Indians (17th Century through Early 19th Century) (1958), and A.C. Isenberg, The Destruction of the Bison: An Environmental History, 1750-1920 (2020))

As with the past essay, the key statement we are really assessing here is this one by George R.R. Martin:

The Dothraki were actually fashioned as an amalgam of a number of steppe and plains cultures… Mongols and Huns, certainly, but also Alans, Sioux, Cheyenne, and various other Amerindian tribes… seasoned with a dash of pure fantasy.

A statement which claims, quite directly, that the Dothraki are modeled primarily off of both Eurasian Steppe nomads and Great Plains Native Americans (with a ‘dash’ of fantasy). Last time, we found that the appearance of the Dothraki fit almost entirely within the ‘dash’ of fantasy. So this time we will begin to ask the same question about Dothraki culture – to what degree may it be said to be based in any actual historical horse-nomad cultures?

A Feast For People

Now ‘culture’ is such a huge topic, it may well be asked why start with subsistence strategies. The answer is that in the pre-modern world, subsistence was one of, if not the, most dominant factor shaping culture. After all, most people before the industrial revolution spent most of their time just doing the basic activities (herding, farming, spinning, weaving, cooking, etc.) that made survival possible! Government structures, military organization, cultural values, marriage and fertility patterns, social structures all flow out of those things which most people were doing to survive, shaped by the needs of those subsistence strategies.

(A brief pedantic note: this sort of approach to history, beginning with big, slow changing patterns (what I often call here ‘structures’ – not a term I made up, by any means) like climate, geography, subsistence strategies, culture, etc. is generally associated with what is called the Annales school of history, which is a method of history. This framework is often more interested in La longue durée (lit: ‘the (really) long term’) which is just a fancy French way of saying ‘a focus on the long-term historical structures (like those listed above) instead of short-term events (like wars, rulers, that sort of thing).’ As always, this sort of historical theory is a toolbox, not a dogma; different approaches to answer different questions. But in this case, it is handy because of the way that the basic activities necessary for survival in a given climate form a sort of ‘bounding box’ for cultural possibility.)

What is particularly notable is with A Song of Ice and Fire and Game of Thrones is that our viewpoint character for Dothraki culture is a young woman who spends her time with the Dothraki in the khalassar’s (the Dothraki word for a tribe or clan) moving encampment. Daenerys can only really view warfare second hand (at least in the books we get; the show is another matter), but she ought to be able to witnesses the subsistence system directly. Even if she wasn’t involved in it directly (because she’s a high status queen), the daily work of survival would be going on all around her and in practice much of it would likely be at her direction as she exercises authority over lower-status individuals in the camp.

Now normally we would start this by looking at how subsistence strategies are represented in the books and show, but I think in this case it is going to be more helpful to begin with the historical subsistence systems first, since they are complex and we’re going to have several of them. We’re actually going to start at the ending as well, with subsistence strategies of Native Americans on the Great Plains, for reasons that will be clearer once we’ve discussed it.

A Changing of Patterns

The domesticated horse is not native to the Americas. There is perhaps no more important fact when trying to understand how the horse-borne nomadic cultures of the Eurasian Steppe relate to those of the Great Plains. The first domesticated horses arrived in the Americans with European explorer/conquerors and the settler-colonists that followed them. Eventually enough of those horses escaped to create a self-reproducing wild (technically feral, since they were once domesticated) horse population, the mustangs, but they are not indigenous and mustangs were never really the primary source of new horses the way that wild horses on the Steppe were (before someone goes full nerd in the comments, yes I am aware that there were some early equines in the Americas at very early dates, but they were extinct before there was any chance for them to be domesticated).

Horses arrived in the Great Plains form the south via the Spanish and moving through Native American peoples west of the Rocky Mountains by both trade and eventually raiding in the early 1700s. Notably firearms also began moving into the region in the same period, but from the opposite direction, coming from British and French traders to the North and West (the Spanish had regulations against trading firearms to Native Americans, making them unavailable as a source). Both were thus initially expensive trade goods which could only be obtained from outside and then percolated unevenly through the territory; unlike firearms, which remained wholly external in their supply, horses were bred on the plains, but raiding and trade were still essential sources of supply for most peoples on the plains. We’ll get to this more when we talk about warfare (where we’ll get into the four different military systems created by this diffusion), but being in a position where one’s neighbors had either the horse or the gun and your tribe did not was an extreme military disadvantage and it’s clear that the ‘falling out’ period whereby these two military innovations distributed over the area was very disruptive.

But unlike guns, which seem to have had massive military impacts but only minimal subsistence impacts (a bow being just as good for hunting bison as a musket, generally), the arrival of the horse had massive subsistence impacts because it made hunting wildly more effective. But the key thing to remember here is: the horse was introduced to the Great Plains no earlier than 1700, horse availability expanded only slowly over the area, but by 1877 (with the end of the Black Hills War), true Native American independence on the Great Plains was functionally over. Consequently, unlike the Steppe, where we have a fairly ‘set’ system that had already been refined for centuries, all we see of the Plains Native American horse-based subsistence system is rapid change. There was no finally reached stable end state, as far as I can tell.

Though there is considerable variation and also severe limits to the evidence, it seems that prior to the arrival of the horse, most Native peoples around the Great Plains practiced two major subsistence systems: nomadic hunter-gathering on foot (distinct from what will follow in that it places much more emphasis on the gathering part) on the one hand and a mixed subsistence system of small-scale farming mixed seasonally with plains hunting seems to have been the main options pre-horse, based on the degree to which the local area permitted farming in this way (for more on those, note Isenberg, op. cit., 31-40). Secoy (op. cit.) notes that while there is some evidence that the Plains Apache may have shifted through both systems, being hunter-gatherers prior to the arrival of horses, by the time the evidence lets us see clearly (which is shortly post-horse) they are subsisting by shifting annually between sedentary agricultural rancheirias (from the Spring to about August) and hunting bison on the plains during the fall. Isenberg notes the Native Americans of the Missouri river combining corn agriculture with cooperative bison hunting in the off-season (in that case, in the summer). Meanwhile, the Comanches and Kiowas seem to have mostly subsisted on pedestrian bison hunting along with gathering fruit and nuts, with relatively little agriculture, prior to going fully nomadic once they acquired horses. Bison hunting on foot required a lot of cooperation (so a group) and it seems clear that it was not enough to support a group on its own and had to be supplemented somehow, at least before the arrival of the horse. Some mix of either bison+gathering or bison+horticulture was required.

Isenberg argues (op. cit.), that at this point the clear advantage was to what he terms the ‘villagers’ – that is the farmer-hunters who lived in villages, rather than the nomadic hunter-gathers. These horticulturists were more numerous and seem quite clearly to have had the better land and living conditions. Essentially the hunter-gatherers stuck on marginal land were mostly hunter-gatherers because they were stuck on marginal land, which created a reinforcing cycle of being stuck on marginal land (the group is weak due to small group size because the land is marginal and because the group is weak, it is only able to hold on to marginal lands). That system was stable without outside disruption. The horse changed everything.

A skilled Native American hunter on a horse, armed with a bow, could hunt bison wildly more effectively than on foot. They could be found more rapidly, followed at speed and shot in relative safety. It is striking that while pedestrian bison hunting was clearly a team effort, a hunter on a horse could potentially hunt effectively alone or in much smaller groups. In turn, that massively increased effectiveness in hunting allowed the Native Americans of the region, once they got enough horses, to go ‘full nomad’ and build a subsistence system focused entirely on hunting bison, supplemented by trading the hides and other products of the bison with the (increasingly sedentary and agrarian) peoples around the edges of the Plains. Many of the common visual markers of Plains Native Americans – the tipi, the travois, the short bow for use from horseback – had existed before among the hunter-gathering peoples, but now spread wore widely as tribes took to horse nomadism and hunting bison full time. At the same time, Isenberg (op. cit. 50-52) has some fascinating paragraphs on all sorts of little material culture changes in terms of clothing, home-wares, tools and so on that changed to accommodate this new lifestyle. The speed of the shift is quite frankly stunning.

We’ll come back to this later, but I also want to note here that this also radically changed the military balance between the nomads and the sedentary peoples. The greater effectiveness of bison hunting meant that the horse nomads could maintain larger group sizes (than as hunter-gatherers, although eventually they also came to outnumber their sedentary neighbors, though smallpox – which struck the latter harder than the former – had something to do with that too), while possession of the horse itself was a huge military advantage. Thus by 1830 or so, the Ute and Comanche pushed the Apache off of much of their northern territory, while the Shoshone, some of the earliest adopters of the horse, expanded rapidly north and east over the Northern Plains, driving all before them (Secoy, op. cit., 30-31, 33). Other tribes were compelled to buy, raise or steal horses and adopt the same lifestyle to compete effectively. It was a big deal, we’ll talk about specifics later.

Horse supply in this system could be tricky. Unlike in Mongolia, where there were large numbers of wild horses available for capture, it seems that most Native Americans on the Plains were reliant on trade or horse-raiding (that is, stealing horses from their neighbors) to maintain good horse stocks initially. In the southern plains (particularly areas under the Comanches and Kiowas), the warm year-round temperature and relatively infrequent snowfall allowed those tribes to eventually raise large herds of their own horses for use hunting and as a trade good. While Mongolian horses know to dig in the snow to get the grass underneath, western horses generally do not do this, meaning that they have to be stall-fed in the winter. Consequently in the northern plains, horses remained a valuable trade good and a frequently object of warfare. In both cases, horses were too valuable to be casually eating all of the time and instead Isenberg notes that guarding horses carefully against theft and raiding was one of the key and most time-demanding tasks of life for those tribes which had them.

So to be clear, the Great Plains Native Americans are not living off of their horses, they are using their horses to live off of the bison. The subsistence system isn’t horse based, but bison-based.

At the same time, as Isenberg (op. cit. 70ff) makes clear that this pure-hunting nomadism still existed in a narrow edge of subsistence. From his description, it is hard not to conclude that the margin or survival was quite a bit narrower than the Eurasian Steppe subsistence system and it is also clear that group-size and population density were quite a bit lower. It’s also not clear that this system was fully sustainable in the long run; Pekka Hämäläinen argues in The Comanche Empire (2008) that Comanche bison hunting was potentially already unsustainable in the very long term by the 1830s. It worked well enough in wet years, but an extended drought (which the Plains are subjected to every so often) could cause catastrophic decline in bison numbers, as seems to have happened the 1840s and 1850s. A sequence of such events might have created a receding wave phenomenon among bison numbers – recovering after each dry spell, but a little less each time. Isenberg (op. cit., 83ff) also hints at this, pointing out that once one factors for things like natural predators, illness and so on, estimates of Native American bison hunting look to come dangerously close to tipping over sustainability, although Isenberg does not offer an opinion as to if they did tip over that line. Remember: complete reliance on bison hunting was new, not a centuries tested form of subsistence – if there was an equilibrium to be reached, it had not yet been reached.

In any event, the arrival of commercial bison hunting along with increasing markets for bison goods drove the entire system into a tailspin much faster than the Plains population would have alone. Bison numbers begin to collapse in the 1860s, wrecking the entire system about a century and a half after it had started. I find myself wondering if, given a longer time frame to experiment and adapt the new horses to the Great Plains if Native American society on the plains would have increasingly resembled the pastoral societies of the Eurasian Steppe, perhaps even domesticating and herding bison (as is now sometimes done!) or other animals. In any event, the westward expansion of the United States did not leave time for that system to emerge.

Consequently, the Native Americans of the plains make a bad match for the Dothraki in a lot of ways. They don’t maintain population density of the necessary scale. Isenberg (op. cit., 59) presents a chart of this, to assess the impact of the 1780s smallpox epidemics, noting that even before the epidemic, most of the Plains Native American groups numbered in the single-digit thousands, with just a couple over 10,000 individuals. The largest, the Sioux at 20,000, far less than what we see on the Eurasian Steppe and also less than the 40,000 warriors – and presumably c. 120-150,000 individuals that implies – that Khal Drogo alone supposedly has. They haven’t had access to the horse for nearly as long or have access to the vast supply of them or live in a part of the world where there are simply large herds of wild horses available. They haven’t had long-term direct trade access to major settled cities and their market goods (which expresses itself particularly in relatively low access to metal products). It is also clear that the Dothraki Sea lacks large herds of animals for the Dothraki to hunt as the Native Americans could hunt bison; there are the rare large predators like the hrakkar, but that is it. Mostly importantly, the Plains Native American subsistence system was still sharply in flux and may not have been sustainable in the long term, whereas the Dothraki have been living as they do, apparently for many centuries.

So to say the Dothraki share a subsistence system with Great Plains Native Americans is simply wrong. There are complex factors of trade, living-style which simply don’t exist here, the scale is all wrong, as is the ecology. Thus, when it comes to exemplars from a subsistence standpoint, we may safely put the Great Plains to the side.

Well, what about Steppe Nomads?

A Flock of Sheep

The horse is native to the Eurasian Steppe – that is where it evolved and was first domesticated, though the earliest domesticated wild horses were much smaller and weaker (but more robust and self-sufficient) than modern horses. The horse was first domesticated here, on the Eurasian Steppe, by the nomadic peoples there around 3,700 BCE. It seems likely that the nomads of the steppe were riding these horses more or less form the get-go (based on bridle and bit wear patterns on horse bones), but the domesticated horse first shows up in the settled Near East as chariotry (rather than cavalry) around 2000 BCE; true cavalry won’t become prominent in the agrarian world until after the Late Bronze Age Collapse (c. 1200 BCE).

I wanted to start by stressing these dates just to note that the peoples of the Eurasian Steppe had a long time to adapt themselves to a nomadic lifestyle structured around horses and pastoralism, which, as we’ve seen, was not the case for the peoples of the Americas, whose development of a sustainable system of horse nomadism was violently disrupted.

That said, the steppe horse (perhaps more correctly, the steppe pony) is not quite the same as modern domesticated horses. The sorts of horses that occupy stables in Europe or America are the product of centuries of selective breeding for larger and stronger horses. Because those horses were stable fed (that is, fed grains and hay, in addition to grass), they could be bred much larger what a horse fed entirely on grass could support (with the irony that many of those breeds of horses, if released into the wild in their native steppe, would be unable to subsist themselves), because processed grains have much higher nutrition and calorie density than grass. So while most modern horses range between c. 145-180cm tall, the horses of the steppe were substantially smaller, 122-142cm. Again, just to be clear, this is essential because the big chargers and work-horses of the agrarian world cannot sustain themselves purely on grass and the Steppe nomad needs a horse which can feed itself (while we’re on horse-size, mustangs, the feral horses of the Americas, generally occupy the low-end of the horse range as well, typically 142-152cm in height – even when it is clear that their domesticated ancestors were breeds of much larger work horses).

Now just because this subsistence system is built around the horse doesn’t mean it is entirely made up by horses. Even once domesticated, horses aren’t very efficient animals to raise for food. They take too long to gestate (almost a year) and too long to come to maturity (technically a horse can breed at 18 months, but savvy breeders generally avoid breeding horses under three years – and the Mongols were savvy horse breeders). The next most important animal, by far is the sheep. Sheep are one of the oldest domesticated animals (c. 10,000 BC!) and sheep-herding was practiced on the steppe even before the domestication of the horse. Steppe nomads will herd other animals – goats, yaks, cattle – but the core of the subsistence system is focused on these two animals: horses and sheep. Sheep provide all sorts of useful advantages. Like horses, they survive entirely off of the only resource the steppe has in abundance: grass. Sheep gestate for just five months and reach sexual maturity in just six months, which means a small herd of sheep can turn into a large herd of sheep fairly fast (important if you are intending to eat some of them!). Sheep produce meat, wool and (in the case of females) milk, the latter of which can be preserved by being made into cheese or yogurt (but not qumis, as it will curdle, unlike mare’s milk). They also provide lots of dung, which is useful as a heating fuel in the treeless steppe. Essentially, sheep provide a complete survival package for the herder and conveniently, made be herded on foot with low manpower demands.

Now it is worth noting right now that Steppe Nomads have, in essence, two conjoined subsistence systems: there is one system for when they are with their herds and another for purely military movements. Not only the sheep, but also the carts (which are used to move the yurt – the Mongols would call it a ger – the portable structure they live in) can’t move nearly as fast as a Steppe warrior on horseback can. So for swift operational movements – raids, campaigns and so on – the warriors would range out from their camps (and I mean range – often we’re talking about hundreds of miles) to strike a target, leaving the non-warriors (which is to say, women, children and the elderly) back at the camp handling the sheep. For strategic movements, as I understand it, the camps and sheep herds might function as a sort of mobile logistics base that the warriors could operate from. We’ll talk about that in just a moment.

So what is the nomadic diet like? Surely it’s all raw horse-meat straight off of the bone, right? Obviously, no. The biggest part of the diet is dairy products. Mare’s and sheep’s milk could be drunk as milk; mare’s milk (but not sheep’s milk) could also be fermented into what the Mongolians call airag but is more commonly known as qumis after its Turkish name (note that while I am mostly using the Mongols as my source model for this, Turkic Steppe nomads are functioning in pretty much all of the same ways, often merely with different words for what are substantially the same things). But it could also be made into cheese and yogurt [update: Wayne Lee (@MilHist_Lee) notes that mare’s milk cannot be made into yogurt, so the yogurt here would be made from sheep’s milk – further stressing the importance of sheep!] which kept better, or even dried into a powdered form called qurut which could then be remixed with water and boiled to be drunk when it was needed (this being a dried form of yogurt, it would presumably be made from sheep’s milk, as mare’s milk wasn’t used for yogurt). The availability of fresh dairy products was seasonal in much of the steppe; winter snows would make the grass scarce and reduce the food intake of the animals, which in turn reduced their milk production. Thus the value of creating preserved, longer-lasting products.

Of course they did also eat meat, particularly in winter when the dairy products became scarce. Mutton (sheep meat) is by far largest contributor here, but if a horse or oxen or any other animal died or was too old or weak for use, it would be butchered (my understanding is that these days, there is a lot more cattle on Mongolia, but the sources strongly indicate that mutton was the standard Mongolian meat of the pre-modern period). Fresh meat was generally made into soup called shulen (often with millet that might be obtained by trade or raiding with sedentary peoples or even grown on some parts of the steppe) not eaten raw off of the bone. One of our sources, William of Rubruck, observed how a single sheep might feed 50-100 men in the form of mutton soup. Excess meat was dried or made into sausages. On the move, meat could be placed between the rider’s saddle and the horse’s back – the frequent compression of riding, combined with the salinity of the horse’s sweat would produce a dried, salted jerky that would keep for a very long time.

(This ‘saddle jerky’ seems to gross out my students every time we discuss the Steppe logistics system, which amuses me greatly.)

Now, to be clear, Steppe peoples absolutely would eat horse meat, make certain things out of horsehair, and tan horse hides. But horses were also valuable, militarily useful and slow to breed. For reasons we’ll get into a moment, each adult male, if he wanted to be of any use, needed several (at least five). Steppe nomads who found themselves without horses (and other herds, but the horses are crucial for defending the non-horse herds) was likely to get pushed into the marginal forest land to the north of the steppe. While the way of life for the ‘forest people’ had its benefits, it is hard not to notice that forest dwellers who, through military success, gained horses and herds struck out as steppe nomads, while steppe nomads who lost their horses became forest dwellers by last resort (Ratchnevsky, op. cit., 5-7). Evidently, being stuck as one of the ‘forest people’ was less than ideal. In short, horses were valuable, they were the necessary gateway into steppe live and also a scarce resource not to be squandered. All of which is to say, while the Mongols and other Steppe peoples ate horse, they weren’t raising horses for the slaughter, but mostly eating horses that were too old, or were superfluous stallions, or had become injured or lame. It is fairly clear that there were never quite enough good horses to go around.

The other major source of meat, especially when on campaign, but also when in camp, would be hunting. One might expect the mighty Mongols to only hunt the more fearsome game, but the most common animals to hunt were smaller ones like the marmot, although the Mongols would hunt essentially anything on the steppe, including deer, antelope, even bears and tigers. Mongol hunting practices are quite developed (especially the large group hunt known as the nerge, which we’ll talk about when we get to warfare). Hunting, especially hunting small game with a bow from horseback, was a skill a good steppe nomad learned very young; one source describes Mongol boys learning to ride on the backs of sheep and practicing their archery by shooting small game (May, op. cit. 42), which is both adorable and terrifying. Needless to say, a warrior who can drop on arrow at distance onto a marmot while riding at speed on a horse is going to be a quite lethal archer in battle.

A String of Horses

War parties, as noted, often moved without bringing the entire camp, the non-combatants or the sheep with them. This was actually crucial operational concern on the steppe, since the absence of a war party might render an encampment – stocked full of the most valuable resources (livestock, to be clear) – effectively unguarded and ripe for raiding, but at the same time, attempting to chase down a moving encampment with an equally slow moving encampment was obviously a non-starter. Better to race over the steppe, concealed (as we’ll see) and quick moving to spring a trap on another group of nomads. But how did a war party make those high speed long-distance movements over the steppe? Horse-string logistics (a term, I should note, that I did not coin, but which is too apt not to use).

Each steppe warrior rode to battle with not one horse, but several: typically five to eight. For reasons that will rapidly become obvious, they preferred mares for this purpose. The Steppe warrior could ride the lead horse and keep the rest of them following along by connecting them via a string (thus ‘horse-string logistics’), such that each steppe warrior was his own little equine procession. These horses are, you will recall, fairly small and while they are hardy, they are not necessarily prodigiously strong, so the warrior is going to shift between them as he rides, sparing his best mount for the actual fight. Of course we are not looking at just one warrior on the move – that would be very dangerous – but a group on the move, so we have to imagine a large group (perhaps dozens or hundreds or even thousands) of warriors moving, with something like 5-8 times that many horses.

[Edit: It is worth noting that a horse-string war party might well also bring some number of sheep with them as an additional food supply, herding them along as the army rode. So even here, sheep maintain their importance as a core part of the subsistence system.]

Now of course the warriors are going to bring rations with them from the camp, including milk (both liquid in leather containers and dried to qurut-paste) as well as dried meat (like the saddle jerky discussed above). But the great advantage of moving on mares is that they when they are lactating, mares are already a system for turning the grass of the steppe into emergency rations. As Timothy May (op. cit.) notes, a mare produces around 225-2.5 quarts of milk in excess of the needs of her foal per day during her normal five-month lactation period, equal to about 1,500kcal/day, half of the daily requirement for a human. So long as at least two of the horses in the horse-string were lactating, a steppe warrior need not fear shortfall. This was more difficult in the winter when less grass was available and thus mare’s milk became scarce, which could impose some seasonality on a campaign, but a disciplined band of steppe warriors could move massive distances (the Mongols could make 60 miles a day on the move unencumbered, which is a lot) like this in just a few months.

In adverse conditions (or where time permitted because meat is tasty), steppe warriors on the move could also supplement their diet by hunting, preserving the meat as saddle-jerky (discussed above). In regions where water became scarce, we are frequently told that the Mongols could keep going by opening a vein on their horse and drinking the blood for both nourishment and hydration; May (op. cit.) notes that a horse can donate around 14 pints of blood without serious health risk, which is both hydrating, but also around 2,184kcal, about two-third of the daily requirement. This will have negative impacts on the horses long term if one keeps doing it, so it was an emergency measure.

The major advantage of this kind of horse-string logistics was that a steppe warrior party could move long distances unencumbered by being essentially self-sufficient. It has a second major advantage that I want to note because we’ll come back to it, they light no fires. For most armies, camp fires are essential because food preparation – particularly grains – essentially requires it. But a steppe warrior can move vast distances – hundreds of miles – without lighting a fire. That’s crucial for raiding (and becomes a key advantage even when steppe warriors transition to taking and holding territory in moments of strength, e.g. the Mongols) because sight-lines on the steppe are long and campfires are visible a long way off. Fireless logistics allow steppe warriors to seemingly appear from the steppe with no warning and then vanish just as quickly.

That said, these racing columns of steppe warriors, while they could move very fast and be effectively independent in the short term, don’t seem generally to have been logistically independent of the camp and its herds of sheep in the long term. Not only, of course, would there be need for things like hides and textiles produced in the camp, but also the winter snows would drastically reduce the mares milk the horses produced, making it more difficult to survive purely on horse-string logistics. Instead, the camp formed the logistical base (and store of resources, since a lot of this military activity is about raiding to get captives, sheep and horses which would be kept in the camp) for the long range cavalry raids to strike out from. To the settled peoples on the receiving end of a Mongol raid, it might seem like the Mongols subsisted solely on their horses, but the Mongols themselves knew better (as would anyone who stayed with them for any real length of time).

A Subsistence of Steppes

All of that discussion done, we come to the question, what would an outsider observe when viewing the Steppe subsistence system? After all, what we are really assessing here is a portrait of a Steppe society as viewed by an outsider (conveniently, a lot of the evidence that forms the backbone of our discussion so far is exactly this; check out May, op. cit. for more on that). And I certainly don’t expect Martin (or the showrunners) to bring their story to a screeching halt in order to discuss horse lactation schedules and making dairy products. So if we were in, say a Mongol camp (keeping mind that a Turkic or Hunnic or Scythian nomad camp wouldn’t be very different), what might we see?

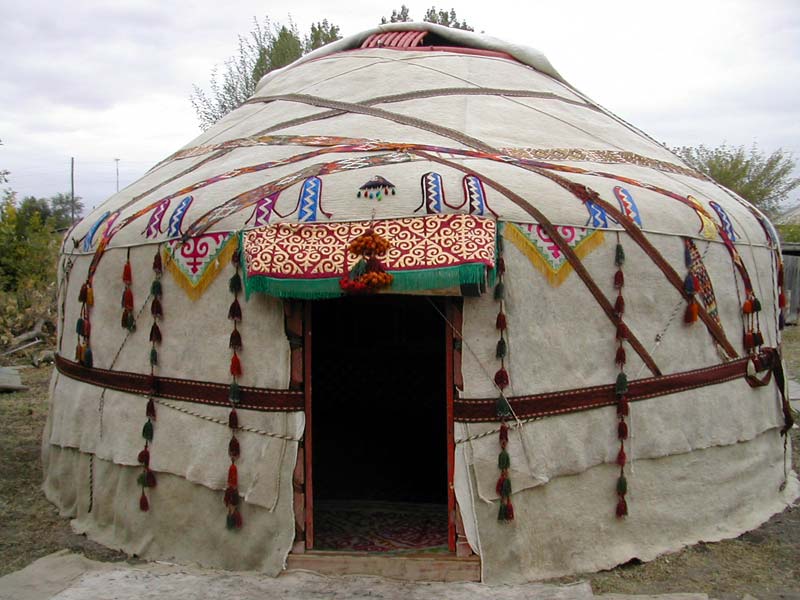

The primary camp structure is the ger (the Mongolian term) or a yurt (the Old Turkic word) – a portable round tent, typically fairly large, covered with a mix of felt and hides. The ger is one of those structures which, having presumably been incrementally improved over centuries, is just really impressive for its simplicity and elegance. The ger can open at the top to allow a fire to be kept inside (and smoke to escape) in cold climates and additional layers or felt, hide or fur can be easily wrapped over the basic frame to provide insulation to hold in that heat. In hot weather, the coverings can be changed out for thinner felts and even be lifted to provide air circulation. Meanwhile, the pole construction is stable and sturdy. Most importantly, a good ger in the hands of experienced nomads is stunningly portable – often just a couple of hours to either break down or set up, and the entire assembly – the poles, felt panels, hide covers, all of it – can be stored on a single cart. A large encampment would have many of these, probably around one for every ten or fifteen people or so, very roughly. Of course, since the gers move on the carts, they cannot go with the war party, but have to stay with the moving encampment, so a figure like Daenerys would always be in the same place as the carts with the gers.

Anyone staying there for even a brief span of time is likely to observe the encampment’s many animals, both the horses but also the sheep, along with other animals (cattle, yaks, etc). Wealth in nomadic society is fundamentally measured in animals (especially sheep and horses) so the guest of a powerful, wealthy khan is likely to see a lot of animals. Moreover, they are going to see people spend a lot of time tending these animals. Ewes and mares will be milked, some animals (particularly sheep) may be slaughtered for meat. The sheep would be sheared for wool. Textile production was a task for the women of the encampment; producing fabric from raw wool is labor intensive and would be a fairly constant activity in order to provide the thick wool felt that is used to make everything from clothing to the walls of the yurts themselves. Likewise, dairy processing – turning the milk into cheese, yogurt or qumis – is going to be a constant background activity; qumis, like churning butter, has to be agitated while it ferments, often hundreds of times (although the movement of horses might be used to provide the agitation on the move).

And of course the animals themselves have to be sustained, taken out to graze near the camp, moved between pastures to avoid stripping the grass. Needless to say, animal husbandry can be a lot of work! The camp’s movements itself would not have been random. This is a common error with nomads, assuming they just ‘wander.’ Instead, tribal groupings of various sizes had territory they controlled and shifted, typically in a regular seasonable order, between camp sites to allow the grass in each area to grow back. Trespass on such territory was met with violence, since the trespassers’ animals were literally eating the very basis of the subsistence of the controlling group (we’ll get to it later, but it is odd that the Dothraki Sea seems to lack such territories and also seems to lack ethnic divisions of any kind).

In short, the subsistence system would be in evidence almost everywhere since so much of the activity that goes on in the camp was oriented around the pastoral system.

A Show of Brown

Which, at last brings us back to A Song of Ice and Fire and Game of Thrones. We can start with the show, because visual storytelling is easier to assess. We are able to see Khal Drogo’s khalasaar on the move:

Now to be clear, this is not a war-party, Daenerys is here and we see women and even people (potentially slaves, given the Dothraki attitudes about ‘walkers’) on foot carrying supplies. But where are the herds of sheep? Or even the herds of spare horses? We see one rider for each horse. This isn’t a budget issue, they clearly have a lot of horses, they’ve simply put too many people in the shot; they need to fire about 4/5ths of their extras. And where are the loaded carts carrying the gers? Because, in the show at least, they do have some kind of shelter:

Now, credit where credit is due: those are clearly a kind of shelter, albeit rather small. Not quite a yurt or a tipi, but perhaps a wigwam. That said, for open steppe like this, this isn’t exactly a great design. First off, they appear somewhat poorly made for what are presumably portable, reusable structures (one assumes they are not butchering and tanning all that hide every night). As you will notice above, a Mongolian ger is typically a fairly carefully made thing (people like nice things!) and Native American tipis and wigwams are no different! The choice to shape them as wigwams is not great either: wigwams were generally temporary and non-portable structures, as I understand it; the tipi was designed for repeated use, variable climates and portability and would be a much better choice for this (but I think a ger would be the more correct choice for how the Dothraki are set up, especially since they have carts). In this case, the huge, show-stopping problem is the clear lack of any smokehole at the top of the structure, making it impossible to light a fire inside without smoking yourself to death. Still, within the limits of a show, at least they have dwellings of some sort. They’re not good dwellings, certainly not the sort of dwellings I’d suspect of centuries of development, but they exist.

We also see at least some subsistence activity in the camp, but it is entirely the processing of what look like hunted animals, although in one scene it looks like Drogo does, in fact, own a whole two goats that have been brought along and should feed his immediate household for an afternoon or so. Credit where credit is due, there is one extra in this scene who looks to be rolling something that may be her pressing cheese. More confusing to me is why the men are singularly uninvolved in preparing the meat from animals – the deer and rabbits – that are clearly hunted. That’s a skill they would have, since they must regularly hunt well away from the main encampment! I guess manly men don’t field dress hunted animals?

[Update: I have subsequently learned that in fact men generally did not field-dress their own hunted kills in the Steppe and possibly also the Great Plains. So mea culpa, this one bit in the show is actually reasonable. Another point, surprisingly, for the Game of Thrones set crew over the books, which don’t include this element.]

In short, no subsistence system we have discussed is displayed in the show: there are no big-game bison being processed here which could actually feed this large assemblage of people (that one deer and three rabbits sure won’t do it) and there is no flock of sheep that can do the job either. Now I am usually pretty inclined to give the set team a pass on these sorts of things, but the dialogue makes clear that the absence of those systems is quite intentional. Jorah flatly tells Daenerys, when she asks for literally any food that isn’t horse, “The Dothraki have two things in abundance, grass and horses; people can’t live on grass” (S1E2). Given that he is handing her a bit of horsemeat, we may assume he is both serious and at this point also more or less accurate about the diet (which is, at this point, his diet too!). So the show is quite clear, in its text, that the primary thing the Dothraki are supposed to be eating is horse, only mildly supplemented by other game. But as we have noted, neither the Steppe or Great Plains subsistence system is built around eating horses – instead they are both built around using horses to get another animal to mostly eat, either herding domesticated sheep or hunting wild bison.

That said, I cannot really fault the show, because this is one of the rare cases where the show has managed to do somewhat better than the books, mostly, it seems, by dint of the set crew being forced to put something in the background and ‘generic Hollywood camp’ (‘let’s see, someone’s got some stew going, people vaguely doing something nondescript in the stream, what else? Or right, let’s just put a random animal up on a rack over here…’) at least fills in some standard subsistence tasks and putting those two goats and the one deer in the background could at least be taken to imply that there are a lot more of these somewhere, even though the dialogue of the show rules them out as major food sources.

An Error of Books

No, the problem here isn’t with the show, it is with the show’s source material. So let’s go through it, starting with the least important things. Where the show had sensibly added yurts and merely forgot to have any way to move them, Martin has the Dothraki live in “palaces of woven grass” (AGoT, 83) which I assume the show did not replicate because the moment someone described doing that everyone realized what a bad idea it was and moved on to something more sensible like a yurt covered in leather. Grass and reeds, of course, can be woven. However, as anyone who has done so will tell you, the idea of trying to weave what is essentially a grass basket the size of a tent in a single day is not an enviable – or remotely possible – task. Trying to move such a giant grass basket without it coming apart or developing tears and gaps is hardly better. And at the end, a woven-grass structure wouldn’t even really be particularly good at controlling temperature, which is its entire purpose! It is rather ironic, given that unlike the show’s Dothraki, Martin’s Dothraki do seem to use at least some carts, because Viserys is forced to ride in one (AGoT, 323) and so could bring yurts with them. The just don’t.

More to the point, it is very clear that Martin imagines the Dothraki subsistence system to consist almost entirely of horses. The Dothraki ride horses, they eat horses, they drink fermented mare’s milk. The Dothraki – as in the show – are presented as eating almost entirely horsemeat. They eat horsemeat at the wedding (AGoT, 84), and Daenerys’ attendants are surprised that she asks for any kind of meat other than horse (AGoT, 129), although Daenerys herself seems to have access to a more agrarian diet (AGoT, 198) and other characters observe that the Dothraki prefer horsemeat to anything else (AGoT, 272). There is no mention of herds of anything except people and horses moving with the khalasaar. There is also no sense that the Dothraki are hunting big game like one would in the Great Plains; Drogo kills a hrakkar – a sort of lion, apparently – as a display of bravery (AGoT, 495) but there is nothing that would suggest the kind of bison-based subsistence system (at the very least, if that was the system, Daenerys would be well aware of it, because the camp would be awash in bison-products). I found no references to larger game and the Wiki only offers, “packs of wild dogs, herds of free-ranging horses, and rare hrakkar” which is, needless to say, not enough to make up for the absence of large herds of bison, especially for trying to feed Drogo’s camp of perhaps a hundred thousand people (or more!).

They clearly do not herd sheep. This becomes painfully obvious with the raid on the Lhazareen village. The Dothraki – Khal Ogo’s men – in raiding a sedentary pastoralist settlement, kill all of the sheep and leave them to rot. Dany sees them “thousands of them, black with flies, arrow shafts bristling from each carcass” and only knows that this isn’t Drogo’s work because he would have killed the shepherds first (AGoT, 555). And we are told that the people there “the Dothraki called them haesh rakhi, the Lamb Men….Khal Drogo said they belong south of the river bend. The grass of the Dothraki sea was not meant for sheep” (AGoT, 556). We are told that the Dothraki have “vast herds” but this can only mean herds of horses, given that they apparently take offense at any other animal being grazed on the Dothraki and look down ad shepherds in general (AGoT, 83). To be clear, for a nomadic people moving over vast grassland to spurn the opportunity to capture vast herds of sheep would be extraordinarily stupid. At the very least, thousands of sheep are valuable trade goods that can literally walk themselves to the point of sale (we’ll get to this idea that the Dothraki also don’t understand commerce a little later, but it is also intense rubbish; horse nomads in both the New World and the Old understood trade networks quite well and utilized them adroitly). But more broadly, as I hope we’ve laid out, sheep are extremely valuable for subsistence in Steppe terrain.

But Martin does not even do horse-string logistics right. While Daenerys eats cheese (AGoT, 198), we never hear of the Dothraki doing so. The Dothraki do have an equivalent to qumis, but no qulut, no yogurt. Even the frankly badass bit about drinking the horse’s blood as a source of nourishment does not appear.

The horses themselves are also wrong. First, Daenerys and Drogo each have one horse they use, seemingly to the exclusion of all others. If you have been reading this long, you know that is nonsense: they ought to both (and Jorah too, if he intends to keep up) be shifting between multiple horses to avoid riding any of them into the ground. Moreover, Martin has imported a European custom about horses – that men ride stallions and women ride mares – into a context where it makes no sense. Drogo’s horse is clearly noted as a red stallion (AGoT, 88) while Daenerys’ horse is a silver filly (AGoT, 87). But of course the logistics of Steppe raiding revolves around mares; in trying to give Drogo the ultimate manly-man horse, he has actually given him the equivalent of a broken down beater – a horse only able to fulfill a slim parts of its role.

Finally, the group size here is wildly off. For comparison, Timothy May estimates that, in 1206, when Temujin he took the name Chinggis Khan and thus became the Great Khan, ruling the entire eastern half of the Eurasian Steppe, that the Mongol army “probably numbered less than a hundred thousand men” (May, The Mongols, (2019), 43), though by that point his army included not merely Mongols, but other ethnically distinct groups of steppe nomads, Merkits, Naimans, Keraites, Uyghurs and the Tatars (the last of which Chinggis had essentially exterminated – next time, we’ll get to the nonsense of the Dothraki being a single ethnic group). That is, to be clear, compared to the armies of sedentary empires of similar size (which is to say, huge) a fairly small number! We’re going to come back to this next week, but the strength of Steppe nomads was never in numbers. Pastoralism is a low density subsistence strategy, so the steppe nomads were almost always outnumbered by their sedentary opponents (Chinggis himself overcomes this problem by folding sedentary armies into his own, giving him agrarian numbers, backed by the fearsome fighting skills of his steppe nomads).

Khal Drogo’s khalasaar, which moves as a single unit, supposedly has 40,000 riders (AGoT, 325-6); Drogo is perhaps the strongest Khal, but still only one of many. With 40,000 riders, we have to imagine an entire khalasaar of at least 120,000 Dothraki (plus all the slaves they seem to have – put a pin in that for later; also that number is a low-ball because violent mortality is clearly very high among the Dothraki, which would increase the proportion of women and children) and probably something like 300,000 horses. At least. Of course no grassland could support those numbers without herds of sheep or other cattle. As noted above, Isenberg’s figures suggest much lower density in the absence of herding – just under 70,000 nomadic Native Americans on the Great Plains in 1780 (and less than 40,000 in 1877), including women and children! But more to the point, no assemblage of animals and people that large could stay together for any length of time without depleting the grass stocks.

Even if we ignore that problem and even if we assume that the Dothraki have Mongol-style pastoral logistics to enable higher population density on the Dothraki Sea, my sense is that the numbers still don’t work. Even before Drogo dies, we meet quite a few other independent Khals with their on khalasaars – Moro, Jommo, Ogo, Zekko and Motho at least and it is implied that there are more. Drogo’s numbers suggests he should be roughly at the stage Chinggis Khan was in 1201 or so – with Chinggis controlling roughly half of the Mongolian Steppe, and his old friend and rival Jamukha the other half. But Khal Drogo has evidently at least a half-dozen rivals, probably more. It is hard to say with any certainty, but the numbers generally seem too high. Having that entire group concentrated, moving together for at least nine months (long enough for Daenerys to become pregnant and give birth) would be simply impossible inside of a grazing-based subsistence system, sheep or no sheep.

In short, no part of this subsistence system works, either from a North American or a Eurasian perspective.

A Tome of Changing Land Use Patterns

[Note: Parts of this conclusion were moved to Part III of this series, because they made more sense there. Alas for the perils of serialized publication! So if you see someone in the comments still talking about something I said that isn’t here, check to see if it isn’t in the conclusion there.]

This isn’t actually much of a surprise. Martin has been pretty clear that he doesn’t like the kind of history we’re doing here. As he states:

I am not looking for academic tomes about changing patterns of land use, but anecdotal history rich in details of battles, betrayals, love affairs, murders, and similar juicy stuff.

That’s an odd position for an author who critiques other authors for being insufficiently clear about their characters’ tax policy (what does he think they are taxing, other than agricultural land use?). Now, I won’t begrudge anyone their pleasure reading, whatever it may be. But what I hope the proceeding analysis has already made clear is that it simply isn’t possible to say any fictional culture is ‘an amalgam’ of a historical culture if you haven’t even bothered to understand how that culture functions. And it should also be very clear at this point that George R. R. Martin does not have a firm grasp on how any of these cultures function.

Once again, Martin has instead constructed this culture out of stereotypes of nomadic peoples. Indeed, Timothy May, in writing, notes himself the stereotype that the Mongols were always eating big haunches of meat (The Mongol Art of War, 60-1) or that the Mongols were numerous beyond counting (The Mongols, 43) and points out that these are both longstanding stereotypes but also straight nonsense. And that straight nonsense, along with at least having heard of qumis, appears to be the sum total of Martin’s understanding of steppe logistics.

Hardly a promising start to our look at Dothraki culture. So far our ‘dash of fantasy’ has turned into a barrel of salt. Next week, we keep digging in the salt to see if we can find any real culture there at all.

Hey hey, we haven’t had a Tolkien intrusion into the discussion yet, so let me open the breach. How does all this apply to Rohan? Letter 297: “Rohan. I cannot understand why the name of a country (stated to be Elvish) should be associated with anything Germanic; still less with the only remotely similar O.N. rann ‘house’, which is incidentally not at all appropriate to a still partly mobile and nomadic people of horse-breeders!”

So he thought of them as somewhat nomadic, even if that wasn’t clear in LotR. Though we do have “the Horse-lords had formerly kept many herds and studs in the Eastemnet, this easterly region of their realm, and there the herdsmen had wandered much, living in camp and tent, even in winter-time. But now all the land was empty, and there was a silence that did not seem to be the quiet of peace.”

“Their horses were of great stature”

“‘There are three empty saddles, but I see no hobbits,’ said Legolas.” — no remounts.

Some spare horses in RotK: “There on the wide flats beside the noisy river were marshalled in many companies well nigh five and fifty hundreds of Riders fully armed, and many hundreds of other men with spare horses lightly burdened.”

The Rohirrim seem to love their horses too much to eat them, and Tolkien was English, and the English abhor horsemeat. No mention of any kind of milk or other dairy products… really, no mention of Rohan food at all. No mention of sheep or cattle, just “herds”. (Though Appendix A does mention a loss of cattle and horses in Helm’s time.) There is mention of homesteads, and “But great store of food, and many beasts and their fodder”

So I think we’re supposed to believe in Rohirrim farmers to the south and west, and great herds of horses living on the grass to the north and east, with these grass-fed horses being big enough to carry tall warriors in long mail without a need for spare horses.

I am not sure it actually coheres.

The Wainriders and other invaders from the east are probably more like steppe nomads; Tolkien doesn’t given enough detail to get it wrong. In Unfinished Tales he does say they trained their women in fighting:

“The revolt planned and assisted by Marhwini had indeed broken out; desperate outlaws coming out of the Forest had roused the slaves, and together had succeeded in burning many of the dwellings of the Wainriders, and their storehouses, and their fortified camps of wagons. But most of them had perished in the attempt; for they were ill-armed, and the enemy had not left their homes undefended: their youths and old men were aided by the younger women, who in that people were also trained in arms and fought fiercely in defence of their homes and their children. Thus in the end Marhwini was obliged to retire again to his land beside the Anduin”

Eowyn seems to have been trained as well, but there’s no mention of women Rohirrim fighting even in an existential defensive war.

Eomer was in charge of a small band going out to deal with a small band of enemy. Resupply was less urgent. Note they also had no baggage

Without refreshing to see whether I have duplicated someone else’s typo corrections posted after I started reading, here is my list, with the duplicates I *did* see, removed:

able to witnesses the subsistence -> able to witnesses

hunting seems to -> [could you go back and look at the construction of the sentence this comes from? It is rather confusing at first to follow from a second example into its predicate part of the sentence/?]

big deal, we’ll -> (comma ought to be semicolon)

makes clear that this -> makes clear[comma] this (delete that)

as long or have access -> had

or live in a part -> lived (Bret, if these corrections are not right, then please address your changing tenses more clearly/?)

Mostly importantly, -> Most

look down ad shepherds -> look down at

(and less than 40,000 -> fewer than

I hope the proceeding analysis -> preceding

A short range mission wouldn’t need much baggage but there might have been remounts, they wouldn’t be wearing saddles and Legolas specifically says saddles not riderless horses.

I find the Wainriders furiously interesting and deeply regret not having more info about them. I imagine them to be something like the Sarmatians.

Typo squid assmeble!

“form the south” -> “from the south”

“now spread wore widely” -> “now spread more widely”

“to full a travois” -> “to pull a travois”

“and a frequently object” -> “and a frequent object”

“the margin or survival” -> “the margin of survival”

“form the get-go” -> “from the get-go”

“Steppe nomads […] without horses […] was” -> “were”

“steppe live” -> “steppe life”

“sheep on the foreground ” -> “sheep in the foreground”

“drop on arrow” -> “drop an arrow”

“was actually crucial operational” -> “was actually a crucial operational”

“and quick moving to spring” -> “and moving quickly to spring” ? “and quick moving, to spring” – probably the latter

” fulfill a slim parts” -> “fulfill slim parts” or “fulfill a slim part”

Weird sentences, etc:

“For reasons we’ll get into a moment, each adult male, if he wanted to be of any use, needed several (at least five). ” – presumably each adult _human_ male needed several _horses_ but that took a few scans to parse

Bit of a maths question:

“a mare produces around 225-2.5 quarts of milk in excess of the needs of her foal per day” – Were the war parties bringing the foals along, too? Seems like you wouldn’t need more than a single mare in your train to stay fed, though presumably at least two would be safer in case something happened to one.

And then one odd followup:

“But more to the point, no assemblage of animals and people that large could stay together for any length of time without depleting the grass stocks.” This does seem to be one bit where Martin applies a deliberate dash of fantasy, possibly without realizing it. The grass of the region is evidently uncommonly tall. He probably meant it as a way to make the setting more imposing, and also to explain opportunities for stealth (nevermind the fires at camp), but the stock of grass seems more substantial here than in real-world steppes.

That doesn’t solve the issue of the horses themselves being depleted, of course.

And all of that works fine in a mythological story, but Martin’s the one claiming his world has a basis in reality…

One thing I recall from reading about the Mongols is that the aristocracy kept larger horses, which needed grain through the winter. These were the core of armoured lancers who followed up on the disorder created by the horse-archers. Marco Polo remarks on the thousands of camel-loads of grain sent north each year from China to Kubilai’s camp on the steppes. This, along with access to textiles and metalwork, gave the ‘inner steppe’ tribes an advantage over the outer tribes – offset by greater vulnerability to agriculture-based power.

Another note – water as much as grass was a key resource on the steppe. In high summer the herds need huge amounts and ready access.

I think the steppe is better watered than the great plains, in addition to the big rivers like the Volga there are lots of little tributaries. Or so it seems from the account of an eighteenth century russian settler on the steppe.

Depends on area – Morris’ account of Genghis campaign’s against north China mention that crossing the eastern Gobi meant waiting until autumn rains filled the clay pans.

Also, there’s water and there’s access to it. A tumen – 10,000 men and 40,000 horses can literally drink a small stream dry. The major rivers often have steep banks and approached through side-ravines (‘balkas’). A large group would have to split up and use several access points (it would take over a day for even a close-packed and orderly 40,000 horse string to pass a point in single file).

The British Indian army field notes used by Engels (Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army) estimate available forage at various times of the year and how many men and animals the water supplies can support, given access and flow rates.

Very much depends on where you draw the lines (“Is the Gobi desert part of the steppes?”) or where you are.

My informant is Sergey Asakov, a Russian writer who was part of the eighteenth century Russian colonization of the steppe. His grandfather’s homestead was in Bakhshir territory. The settlers chose land near rivers and it’s implied there are plenty to chose from, though many aren’t navigable.

It’s less about water than access. A few herdsmen can take groups of animals to a watering point over the course of the day, and move the herd slowly from one point to another. A military group needs to get the watering done in a limited time-frame and then move on. So a stream whose flow rate would support a few thousand animals over a day may not provide for the same number watering all at once, and a major river might have access points that only allow a limited number at a time. In practice, 10,000 people plus animals and associated support (a standard division, a steppe warrior tumen) seems the maximum practical size this kind of movement allows.

Scythian used geldings and the previous Sintashta-Andronovo culture has a 3-1 ratio of male to female horses in it’s sites. Implying they used mostly male horses. Mongol practices seem to be superior considering how totally they came to dominate the Iranic people’s, but it isn’t in anyway strange a steppe culture would prefer male horses for war.

I don’t think the Scythians were quite as geared to specifically light cavalry war, and male horses have an advantage in the (heavy cavalry) press, since female horses are hesitant to get confrontational with stallions (not sure about geldings). Something similar happens, I believe, with war-elephants—cows do not go toe-to-toe with bulls—which is why they usually use bulls, with the cows used, if at all, for hauling and earth-moving.

Great post as always!

This time, though, I wonder if there isn’t another way to look at it. Specifically, I interpret GRRM’s key quote differently:

> The Dothraki were actually fashioned as an amalgam of a number of steppe and plains cultures… Mongols and Huns, certainly, but also Alans, Sioux, Cheyenne, and various other Amerindian tribes… seasoned with a dash of pure fantasy.

One way to interpret it is that the author adds a dash of fantasy “on top”. If so, we’d expect to see a realistic depiction of steppe/plains nomads – something that closely corresponds to their real-world counterparts – but that also has some new element in addition. For example, maybe they have seers that can foretell the future, or maybe their ruler eats from a magical patch of grass that makes him immortal (or at least not age). But otherwise they should look 99% like reality, and so all the differences you rightfully point out would indicate the author didn’t do what the quote claims to.

But another way to interpret it is that the dash of fantasy is done “first”, and the result grows from there, potentially diverging heavily from the real world counterparts. A small initial difference can lead to large consequences. For example, an author could ask what steppe nomads could look like if their horses could talk. That single change might lead to very large things. The author could still be achieving the goal in the quote even if the end result has huge differences from real-world steppe nomads.

Back to GRRM, maybe the idea here was “what would steppe nomads look like if they had all the horses they could want?” Specifically, one mechanism to achieve that might be to say that in this fantasy world the grass has far more calories than in our world, or maybe that the horses are far more fecund for another reason. That “dash of fantasy” could lead to very big differences. For example, they wouldn’t need sheep. One could imagine that such a culture might focus on horses in an extreme way, even seeing sheep and sheep-owners as inferior. Also, if it’s the grass that is so fruitful, perhaps they kill anyone else that tries to benefit from it, as they would be dangerous competition, leading to “The grass of the Dothraki sea was not meant for sheep.” These nomads would look very different from real-world ones because of their complete focus on horses, including a subsistence model that is 100% horse – but it would still be faithful to the goal in GRRM’s quote.

I don’t know if GRRM had this in mind, of course. But I would guess he at least had the idea of, “what if steppe nomads *really* focused entirely on horses, in an extreme way,” and let the idea go from there, no matter how much it diverged from our reality.

Regardless, I think this post is really important because even without that GRRM quote many people will assume the Dothraki closely represent real-world groups, if only because of obvious similarities like Khal/Khan.

Assuming the Dothraki are the result of that thought experiment, GRRM still apparently hasn’t done the added work of making the thought experiment plausible; if he’d done the extra worldbuilding, he could have slipped in all the supporting details, whether it’s super-nutrient-rich grass, modified horse biology, or what have you. I’ll grant that thought experiments in fantasy or SF don’t always have to be fleshed out, but that tends to work best in short stories (and possibly short novels) where there isn’t a lot of space to go into the world’s mechanics in depth. I hadn’t paid much attention before when I read the novels; in hindsight I’m a little disappointed after reading other F&SF authors who’ve put a lot of care into their worldbuilding. It’s true that making those small changes in your base assumptions changes a lot when you carry them out to their logical conclusions — what’s missing in the books is all the texture and variety that comes of thinking about how those changes impact the characters and their environment. I think the Dothraki would have turned out rather differently if GRRM had done that extra work and re-molded their society and culture accordingly.

I’d also argue that “seasoned with a dash of pure fantasy” isn’t the same as “growing an entirely different culture out of a dash of fantasy” — if what GRRM had meant was the latter, he could have just said so.

I don’t have a citation but the grass of the Dothraki Sea isn’t your regular grass, it’s taller than a man; seemingly much more abundant than your regular Earth steppe grass.

There are places in the United States where the prairie grass will naturally grow taller than a man on horseback. The grass is within the range found among real grasses.

I’d actually kinda like to see the context of that quote, myself. The other time he quoted Martin, as I said in a post that appears to have been eaten by a Grue (as this might be), the author pretty heavily quote mined. As in, he seems to have taken Martin requesting a specific set of good English language Spanish history texts from a fan, presumably to mine for characters and events, based on the convo (hence the thing about “no academic land usage stuff”) as some sort of statement about Martin’s personal views on scholarship.

The way this sentence is written, it implies Timothy May became the Great Khan in 1206 — adding to an already impressive career:

“For comparison, Timothy May estimates that, in 1206, when he took the name Chinggis Khan and thus became the Great Khan, ruling the entire eastern half of the Eurasian Steppe, that the Mongol army “probably numbered less than a hundred thousand men” (May, The Mongols, (2019), 43), though by that point his army included not merely Mongols, but other ethnically distinct groups of steppe nomads, Merkits, Naimans, Keraites, Uyghurs and the Tatars….”

While this is an improvement, it now has a superfluous word.

when Temujin he took the name Chinggis Khan and thus became the Great Khan, ruling the entire eastern half of the Eurasian Steppe

While this is an improvement, it now has a superfluous word.

when Temujin he took the name Chinggis Khan and thus became the Great Khan, ruling the entire eastern half of the Eurasian Steppe

Huh. Don’t know how that happened.

My informant is Sergey Asakov, a Russian writer who was part of the eighteenth century Russian colonization of the steppe. His grandfather’s homestead was in Bakhshir territory. The settlers chose land near rivers and it’s implied there are plenty to chose from, though many aren’t navigable.

I recall that back in the 70-80s in one of his collections, GRRM talked in an essay or a forward or something about how he was fascinated with stories about reality’s search and destroy campaign against romance. (Note that this is from decades ago so I may not be recalling it right.) He wrote a bunch of stories on this theme.

The two I recall are:

“With The Morning Comes Mistfall” about a tourist resort planet where the attraction is “wraiths” who may or may not exist (think Bigfoot). The owner is very unhappy about a debunking scientist who has come to settle the question. He wants the mystery to continue.

“Patrick Henry, Jupiter, and the Little Red Brick Spaceship” about a billionaire who is trying to build a spaceship, but wants it to be a *proper* spaceship, long and silver with fins like in the 1950s scifi movies. He ultimately fails because of competing more practical projects and government interference.

There’s a whole slew of other stories in that same vein. It got really repetitive when I was doing a read-through of his short stories in order. Another famous one is The Way of Cross and Dragon in which claims that Judas rode a dragon get debunked to much sadness.

Often in the end of the story the pragmatists win out over the romantics but it’s a hollow victory.

It doesn’t surprise me. This bit from his official website is my favorite piece of writing by GRRM:

“The best fantasy is written in the language of dreams. It is alive as dreams are alive, more real than real … for a moment at least … that long magic moment before we wake.

Fantasy is silver and scarlet, indigo and azure, obsidian veined with gold and lapis lazuli. Reality is plywood and plastic, done up in mud brown and olive drab. Fantasy tastes of habaneros and honey, cinnamon and cloves, rare red meat and wines as sweet as summer. Reality is beans and tofu, and ashes at the end. Reality is the strip malls of Burbank, the smokestacks of Cleveland, a parking garage in Newark. Fantasy is the towers of Minas Tirith, the ancient stones of Gormenghast, the halls of Camelot. Fantasy flies on the wings of Icarus, reality on Southwest Airlines. Why do our dreams become so much smaller when they finally come true?

We read fantasy to find the colors again, I think. To taste strong spices and hear the songs the sirens sang. There is something old and true in fantasy that speaks to something deep within us, to the child who dreamt that one day he would hunt the forests of the night, and feast beneath the hollow hills, and find a love to last forever somewhere south of Oz and north of Shangri-La.

They can keep their heaven. When I die, I’d sooner go to middle Earth.”

Sadly not very much reflected in his own fantasy writing.

I suppose that GRRM could quite easily hold the opinion that he prefers the softer side of worldbuilding when it comes to fantasy, but knowing that it’s (overly) gritty realism that sells.

Interestingly I’m of a similar opinion to GRRM, in that the drive towards realism is meaning that we’re losing a lot of the wonder that comes with more soft worldbuilding approaches. Hayao Miyazaki of Studio Ghibli fame is a shining example of making this sort of worldbuilding world.

The isues come in trying to blend the two approaches, and which expectation you set up in your readers. I think GRRM’s issue is that he’s set up the reader to expect realism (with a dash of fantasy) and delivered fantasy with a dash of realism (albeit a fair bit larger dash than was typical at the time). If we were expecting the latter then it’s much less of an issue.

“knowing that it’s (overly) gritty realism that sells.”

Except it’s just grit, not realism. Turning The Emerald City into The Dung City is still fantasy, just nasty fantasy.

Very true, although I do feel it’s worth comparing to mainstream fare before the mega-grittyness came in, which was much, much lighter and more idealistic. I wonder which veers closer to the truth (probably neither).

I think it is VERY MUCH reflected in his writing. He’s written a lot of tragedy but it is bright colorful exaggerated tragedy. For example:

-Westeros is England but BIGGER.

-All of the castes are ludicrously huge and elaborate compared to real ones.

-Lots of physical features are exaggerated like the height of several characters.

-The domains of lords are HUGE.

-The Wall is a fantastically inflated Hadrian’s Wall.

-The lineages of the houses go back to the mists of time and are much more storied than real ones (which causes him a lot of problems with the history as there are all of the civil wars in which the losers keep their lands).

-Dothraki hordes are HUGE and exaggerated in various goofy ways like this series is telling us.

-Clothing is bright and extravagant and there are dyed blue beards and all the rest.

-The food, dear god the food.

Just because a lot of the dream is a nightmare doesn’t mean that Westeros doesn’t run on dream logic or that just about everything in the setting isn’t heightened and exaggerated.

I am aware of those things, but I don’t think they mean much. Take Gormenghast, which Martin mentions in the quote. It’s a story about intrigue and backstabbing that takes place in a gargantuan castle, but despite surface similarities it reads nothing like Martin’s. The mood’s completely different: Gormenghast is altogether weirder and more alienating than anything in ASoIaF, despite being very much a nightmare.

The distinction goes back to both creative and stylistic choices. I’d argue ASoIaF owes more to historical fiction than fantasy, in terms of genre conventions, but that doesn’t quite explain it either. The past is a foreign country, and good historical fiction is often bizarre and fantastical in its own way. Martin’s obsession with realism (in ASoIaF, at least) speaks to a desire to make the setting as recognizable to the audience as possible, which stifles any outlandish impulses his work may have inherited from either fantasy or historical fiction.

Romance isn’t just about making things bigger; there are tonal and thematic aspects that are essential to that stylistic approach. Martin’s aforementioned attitude manifests sporadically in ASoIaF, particularly in Sansa’s arc, but only in a peripheral manner.

Gwydden: the comment software won’t let me reply to your comment so I’ll answer you here.

Well, yes, historical fiction (The Accursed Kings specifically) is a huge influence on ASoIaF but everything gets turned up to 11.

As far as the tone you’re right in that it tries to ground things. It reminds me of an old short story of his (the name of which escapes me at the moment) which describes the day to day work of a space shipping company and it ends up being just like a trucking company down to the grubby little details which pisses off the main character since there’s no romance to it.

So there are all kinds of fantasical things (spaceships!) but the way they’re describes they seem more historical (trucking!) until you actually sit down and think about it and see how bizarre and fantastical so many things actually are (the insane architecture of so many of the castles to take just one example) and how so much of his pseudo-history actually makes no sense (like the Dothraki).

Also I think Martin’s tone is consciously shifting throughout the series from a more historical fiction tone to more Lovecraftian horror and he’s doing that consciously with so many seeds of the horror being planted early on, but he just didn’t notice them before of the more grubby tone.

“It reminds me of an old short story of his (the name of which escapes me at the moment) which describes the day to day work of a space shipping company”

“Night Shift”, Amazing Science Fiction, Jan 1973. Collected in “Songs of Stars and Shadows”, 1977.

I found my copy of the latter, if anyone wants the text of the “search and destroy” quote I mentioned above.

He wanted to have Stonehenge AND the mounted knights. 😀 It goes back to the time when Martin worked for Hollywood and kept getting his stuff cut due to budget concerns. Once the problem was a fight of mounted knights at Stonehenge, and he was told that the artificial stones would start to sway and maybe capzise if he had horses running about near them. So he got the stones, but only knights on foot.