I hope everyone will forgive me taking this week to break from our normal diet of history-and-pop-culture (though we are discussing a key historical concept here – it is me after all), but it is the July 4th weekend and I have been meaning to treat this topic for a while now. I must further beg the indulgence, of course, of all of you international readers for I am about to – in the proper tradition of my country- go on at some length about my country. I have at times noted that I chafe at the use of the word ‘nation’ or worse yet ‘nation-state’ to describe my country, the United States of America. And that distinction has come up more than once in the comments, with requests for more to elaborate.

So let’s talk about it. What is a nation and why isn’t the United States one?

But first, before we dive in, as always if you like what you are reading here, please share it. If you want updates whenever a new post appears, you can click below for email updates or follow me on twitter (@BretDevereaux) for updates as to new posts as well as my occasional ancient history, foreign policy or military history musings. Finally, if you really like it, you can support my writing on Patreon.

Nationless States

First, we ought to note at the outset that it is not a new thing to describe the United States as a nation, at least in very general terms. No less authority than George Washington did so in his addresses to Congress and his farewell address, though in reading, Washington’s use of the term is doesn’t quite map on to its modern meaning; he tends to use nation when he wants to stress the constructed unity of the country (as, in the farewell address, the various parts of the country being “directed by an indissoluble community of interest as one nation” despite the fact that he had spent an entire paragraph noting regional differences significant enough that by the technical definition of nation, they ought to disqualify the young republic). Of course the United States has all sorts of ‘national’ things – museums, parks, cemeteries, debt, etc. And this sort of usage – where ‘nation’ is really metonymy for a citizen body and the state that serves them – is well enough so far as it goes, so long as we understand the degree of imprecision.

The problem is when that metonymy (which is using one word in place of another related word, like saying one owns ‘wheels’ instead of an automobile) is mistaken for true, narrow, literal or technical meaning, as if someone thought that putting ‘boots on the ground’ meant that we need only drop some footwear out of a helicopter to solve a problem. One sees this all of the time, where arguments begin from the proposition that there is an identifiable American ‘nation’ (often with an identifiable ‘people’ that excludes quite a number of American citizens) or that the United States is a nation in a narrow sense rather than some other thing, like an ideology. And the error here is simple: by the narrow, technical definition, the United States is not, and has never been, a nation and is unlikely to become one in the near future.

Here it is necessary to clarify that ‘nation’ doesn’t just mean ‘country’ or ‘state.’ After all, there are quite a lot of different kinds of states and countries and only some of them are nations (or nation-states, which is when the nation and the state are coextensive). A ‘country’ is a territory and its associated polity; some countries are not states at all (Wales, for instance, is a country within the multi-national state of the United Kingdom) and while most of the world is divided up into states now, it was not always so. Mongolia was a country long before it was a state, for instance. There are, after all, quite a lot of historical polities which were not states.

And states come in different forms too. Quite a lot of post-colonial states, once one gets into it, are actually composite multi-national states functionally masquerading as nation-states (this, I suspect is one reason they tend to be so fragile; the notional form of the state doesn’t match its actual foundation). There are still several very clearly imperial states on earth as well; one may argue the United States is an empire in the technical sense (though large parts of that argument hinge on either substantially redefining ’empire’ or focusing the argument on Puerto Rico, Guam and American Samoa) but there are also traditional, unambiguous old-fashioned empires still. Several European states still hold vestiges of their old empires, Russia still controls 22 ‘constituent republics’ reflecting areas of non-Russian settlement with functionally no autonomy, making it quite clearly an empire under the traditional definition. And of course the People’s Republic of China also meets that traditional definition, it’s three largest ‘autonomous regions’ (Xinjiang, Tibet and Inner Mongolia) being fairly obvious imperial possessions which are both ethnically different from the PRC itself (which openly presents itself as the Han Chinese national state) and also quite brutally subjugated by that state. Collectively those regions make up more than a third of the land area of the state; China may thus be a nation, but the People’s Republic of China is not a nation-state, it is an empire.

(Since I have opened this can of worms and we are here talking about the United States, I would argue that the better term for the United States’ global network of bases, economic arrangements and alliances is hegemony rather than empire, as a purely descriptive matter. Empire, as a technical term, is a system of direct territorial control (not for nothing does the term come from Latin imperium, meaning ‘command’). The American system, which aims to achieve the same sort of influence without direct territorial control, is something new and properly ought to be recognized as such. Of course new doesn’t necessarily mean good, but that’s an argument for another time.)

The rather unusual modern configuration of states, I think, fools a lot of people into imagining that the nation and its political expression, the nation-state, are the normal way that humans organize themselves. Or alternately that the nation-state is the ideal state. The nation-state, we should clarify, is sometimes framed as what you get when a nation acquires statehood, but quite a number of current nation-states are dictatorships run by individuals for their own benefit and the benefit of their cronies and historically speaking many (potentially most) nation-states emerged as a product of power-consolidation by the state rather than as an expression of the will of the people so the more limited ‘a nation-state is when the boundaries of the nation and the state mostly coincide’ will have to do. And since most of the world’s states right now are nation-states, or at least try to present themselves as such, many people are quick to assume that the nation-state is normal or even the correct form of state; other forms of state are often presented as archaic holdovers from an earlier age.

So What Makes a Nation?

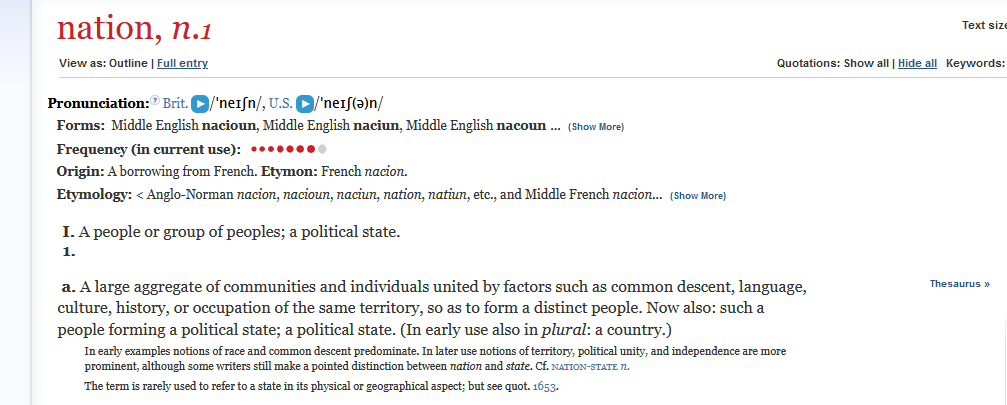

Well, ‘Nation’ is one of those words with a long history and many definitions, some of which are like the metonymy we discussed – rhetorical fudges on the core definition. The root of the word is the Latin natio; it had the narrow meaning of one’s birth. Thus, for instance, Claudia Severa inviting her friend to come ‘ad diem sollemnem natalem meum,’ or “to my birthday party” – natalem here being a form of natalis, the adjective form of natio (that letter, by the way, is fascinating, not only for the look into every day life, but it is also the oldest confirmed example – where we can know and not just guess – of a woman’s own handwriting in Latin and perhaps in any language). But even during antiquity a natio could also mean a common birth, and thus come to mean a breed or species of something and thus a tribe, race or people. From there, the word entered French as nacion, meaning birth or place of origin and from there into English. The definition has changed little, as the fact that classical Latin remained a core part of the education of elites in both the Francophone and Anglophone worlds meant that the meaning of an obvious Latin loanword like ‘nation’ could never drift very far from its original roots. After all until quite recently, elite users of the word were likely to be continually exposed to it in its original, Latin context where it meant ‘birth’ and from there a group of people united by a common birth or origin.

(Latin’s other word for a common descent group, gens, has similar connections, being linked in its origin to gigno, ‘to give birth;’ thus for instance, Venus Genetrix, ‘Venus the birth-mother.’ The usages actually blend further; much like nationes (the plural of natio) could mean, in essence, ‘all of the peoples,’ gentes (the plural of gens) could do the same. Thus, for instance, the Roman ius gentium (often translated as the ‘law of nations’ or ‘law of peoples’) was the law in Rome at applied to all individuals equally, regardless of citizenship or origin, distinct from ius civilis, civil law, with applied to citizens only.)

Consequently, the idea of the ‘nation’ has always been fixed around the notion of a common birth or more correctly the myth of common birth. There are other elements in defining a nation of course: the group typically needs to be large, inhabit a shared, recognizable territory, and share common elements of culture (especially language) and a common history. But it is no accident that the common birth, the natio of nation, is central. A nation, precisely because it is supposed to share a common culture and history, is an entity that is imagined to extend both into the past and into the future, recreating itself, generation to generation; it is through the common birth that the common culture and history are supposedly shared. After all, a common history assumes some commonality stretching back to a prior generation.

Now we ought to be clear here that we are stressing the word ‘myth‘ in ‘myth of common origin’ quite strongly. As demonstrated by the work of folks like Benedict Anderson (Imagined Communities (1983)) and Azar Gat (War in Human Civilization (2006)) the nation in this sense is not a social or political form that exists in the wild, but is instead a thing that humans can invent and is usually the product of state-building rather than an organic cultural expression (for instance, the uniformity of French is a product of the government in Paris’ efforts to make it so, not an organic feature of the ‘French people’). Nations and nationalism and especially nation-states are relatively recent things; we are discussing people who until quite recently did not see themselves as having a common origin or destiny and who now claim their ancestors to have been of common stock typically in contradiction to the views of those very ancestors. Often national myths will paper over this with a myth that the nation was once, in the distant past, a single tribe or polity which expanded, splintered and must now be reunited (you will recall that notion showing up in the Fremen Mirage), but of course polities in the deep past were generally smaller and more fragmented; such myths rarely pan out. None of which is to say that the nation-state is an invalid form of polity, merely that we should not imagine it is the only valid kind of polity or that it is somehow more grounded and organic (or less artificial) than other polities. Like most polities, the nation-state is fundamentally built on a fiction.

As an aside, the traditional view of historians has generally been that nationalism (the ideology) and the nation itself are essentially modern phenomena, emerging in the 18th century. That position has been challenged, with arguments suggesting that various pre-modern polities ought to be understood as nations and even that certain pre-modern rulers harnessed something we might call nationalism in their messaging (e.g. A. Gat, Nations: The Long History and Deep Roots of Political Ethnicity and Nationalism (2012)). My impression is that most historians remain profoundly hesitant to retroject the modern concept of a nation, nationalism and the nation-state back before the late-18th century. I share that hesitance, particularly on the question of if that national feeling extended below the elite in these potential pre-modern nations (which I think is essential for the definition; it isn’t enough for the French nobility to feel French, the French peasantry must as well), but I am not an expert on these particular societies and so reserve judgment. More broadly it seems to me that differences in mass-literacy and communications must make pre-modern nations meaningfully different from modern ones. At the same time, it is hard not to notice the formation of mega-ethnic groups even in the ancient world and the tendency of our sources to think about them in fairly ‘national’ terms; Egypt is often offered as the oldest example and there isn’t nothing to that idea.

The Un-Nation

So we have our definition of a nation: a people, historically connected geographically coherent territory, with a shared language, culture and myth of common birth-origin. The United States obviously fails this definition. It isn’t even remotely close.

To find a common ancestor or ancestral group – a national natio – that connects even a fairly modest majority of Americans, one would have to go back to proto-Indo-European-speakers living in tribes on the Pontic-Caspian Steppe around 5,000 BC or so – a place notably neither within the United States nor hearkened back to as a historical homeland by many Americans. Americans would also share that notional origin, if we go by language, with roughly 3.2 billion people, or about half of all humans on the earth (not all of whom, or – depending on one’s definitions – even most of whom, are white, I should note). Such a classification, “the United States is an Indo-European-speaking country” is true but only a bit more precise than “the United States is a country populated by humans” – the descriptive potential here is very limited. National identities are, after all, not merely about inclusion but also about exclusion; they do not typically overlap. While, as noted above, national myths of common origin generally are myths, in the case of the United States, even the myth-making collapses. Attempting to find a common birth origin for even a slim majority of Americans is a hopeless case (and as far as I can tell, only occurs to people who think ‘European’ is an ethnicity, apparently blissfully unaware that ‘Europe’ is a fairly big place with quite a number of different groups of people).

Common history is likewise a dud here, but that may require a bit more explaining. After all, there are certainly a set of historical events related to the American polity itself – the founding, the American Civil War, the World Wars, the Civil Rights Movement and so on – which form a key pillar of American civics. But these stories are connected to formation of the key institutions of the state; they are not stories of personal origins. While stories of the American founding tends to focus on the role of English settlers, only around 20% of Americans claim British ancestry and about half of those hearken back to Irish immigrants who arrived well after the founding. Needless to say, the ‘common history’ may not seem quite so common for those whose ancestors arrived on slave ships, or many decades after the founding, or the 13.7% of Americans who are foreign born, or, of course, those whose ancestors arrived over the Bering Ice Bridge perhaps twenty thousand years ago. For my own part, my ancestors filtered over the Atlantic during the 1800s and early 1900s; to the best of my knowledge, none of my ancestors fought in the revolution.

(There has been some frustration with that 20% rough figure above. So let’s break it down. The 2015 American Community Survey uses self-reporting; we might quibble with self-reporting if we were trying to actually chart the genetic history of Americans, but we’re not – this is about identity and so self-reporting is actually ideal. The relevant potentially ‘British’ ancestry reports are: Irish (10.6%), English (7.8%), American (7.2%), Scottish (1.7%) and Scotch-Irish (1%). While the survey notes that the English Americans were a meaningful undercount, note that the primary cause of this is those individuals reporting as ‘American’ so by simply including self-reported ‘Americans’ we have recaptured most of that potential undercount. And, because our question is identity, folks who might have English ancestry but identify as, say, Polish-American are safe to remove from the sample. We can also safely remove almost all people reporting Irish descent; the overwhelming majority of Irish Americans arrived in the 1800s. That leaves us adding English + American + Scottish + Scotch-Irish to get people whose reported identity might cause them to hearken back to ancestors who were present and free at the founding and we get 17.7% (7.8+7.2+1.7+1), having recaptured most of the English-ancestry undercount by including everyone identifying as ‘American’ (which in turn also includes a lot of people who don’t think their families go back to the founding). Or – with a generous upward rounding – about 20%. So yes, I did, in fact, account for the undercount of self-reported English-Americans. I’d add that the fact that this group can’t be meaningfully larger than around 20% is also pretty clear from just working backwards from all of the other reported ancestries.)

By raw numbers, none of these origins has much of a claim to be the ‘main’ shared history. This is a striking difference between the United States and many (though not all) other countries which I think isn’t much appreciated; there is no core American ethnicity in the sense of raw numbers. This is often obscured because ethnic distinctions which would be broken out in other countries are collapsed into large categories (like ‘White’ or ‘Hispanic and Latino’) in census documents and discussions. But 76.4% of Germans are ethnic Germans; none of the constituent countries of the UK is below 75% its core ethnic identity. In that context, with the great majority of people having most (or in some cases all) of their ancestors having lived within the bounds of the modern state for generations (in the case of Germany, typically generations before the formation of that state) there really is a ‘shared history’ stretching back quite some distance.

By contrast, as noted, Anglo-Americans make up perhaps as much as 18% of Americans (if we add together ancestry responses of English, Scottish, Scotch-Irish and simply ‘American’), which probably captures the lion’s share of individuals tracing their families back to free persons present at the founding (and a number of people whose families do not go that far). That’s not meaningfully larger than the slice of the country which reports German ancestry (14.7%) most of whose ancestors arrived between 1850 and 1930. It’s also not meaningfully smaller than the slice reporting Italian, Irish and Polish ancestry (collectively around 19%), groups arriving mostly between 1840 and 1910 but who often faced pronounced anti-Catholic bigotry in the predominately protestant United States. And those slices aren’t very different in size from the 12.4% of Americans who report Black African ancestry, most (though not all) of whose ancestors arrived on slave ships between 1619 and 1860. And that isn’t very much larger than the roughly 11% of Americans who report Mexican ancestry. And of course none of these groups is very much larger or smaller than the roughly 14% of Americans who were born somewhere else, immigrated and naturalized.

I could keep going, but the key thing here is that no group is really large enough to demand that their story be the central core narrative. “My ancestors were with the founders” has to coexist with “my ancestors were held in bondage by the founders” has to coexist with “my ancestors got here in the 1800s” with “my ancestors were here before the United States was and were forced in by violence” has to coexist with “my ancestors got here in the 1900s” has to coexist with “hey, I just got here!” For many people, they will have several of those stories in their personal ancestry. There is no single dominant American story, but a collection of American stories, none of which can claim primacy because none of them represent even a significant plurality of the population’s own personal origins, much less a majority. Instead, the core historical narrative that ends up in schools is a civic narrative, focused on the evolution of institutions and key moments shaping the modern idea of American citizenship rather than a national narrative following a specific ethnic group (which is why, despite the United States’ relatively recent origin, that civic narrative is generally not stretched very much further into the past than the colonial era; the history is a history of America, not Americans).

And territory is also a bust. Of course the United States now occupies a defined territory, but as noted, very few Americans have a longstanding attachment to this land stretching into the mists of time. In historical terms, most Americans got here only fairly recently. Moreover, the tale of American expansion is one in which the ‘soil’ of America was repeatedly notional; the United States was where Americans went (and of course we must note that the places they went were not empty, but seized violently from the inhabitants). The United States can travel and indeed has done so. Moreover, ancient claims to the land – either arguments for autochthony or greenfield settlement – for the majority of Americans, are simply impossible; we all know darn well that we weren’t the first people here and that the United States does not have the most ancient claim to this land. Most nations claim to occupy a sacred, ancestral homeland; the United States is fairly open (if quite conflicted) about the fact that it occupies someone else’s sacred, ancestral homeland.

(As a necessary aside, of course there is one group of Americans who can quite correctly claim to have nations of their own: Native Americans. Individual Native American nations check all of the boxes: a historic tie to a territory stretching into the deep past, a myth of common origin, common language, culture and so on. To speak of Native American nations is thus not empty rhetoric, but simply correct usage of the term. Consequently almost everything I say about America and the nation needs a caveat that it doesn’t necessarily apply the c. 1.5% of Americans for are Native Americans, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians or Pacific Islanders; a truly national identity is still an option for those folks if they want it.)

If I may go a step further, it is not merely that America happens not to be a nation, but moreover that to be an American is to reject claims of the nation on one’s self in favor of association on different terms. This is something that makes the United States different from many (though perhaps not all) other non-nation-state polities. Many states which are not nation-states are not because they have some ethnic or national group that lives both on their own traditional land and holding to their own identity, but within the borders of a larger state, either as a subject people (like the Uighurs) or as a constituent people in a multi-national state (like the Scots). They are, in essence, multi-national states, with several nations existing either in a state of equality with each other or a state of domination and subjugation. But to be an American means that someone, somewhere in your heritage (likely many someones) broke the chain of connection between you and whatever mythical notional nation you may have otherwise been part of (mind you, not all Americans’ ancestors were given a choice in that rupture). Of course many Americans may still feel a connection to ‘the old country’ (wherever that may be), but the vision of ‘shared destiny’ that in theory unites a nation is shattered by adopting a different land, a different state and in most cases a different language and culture. Often at considerable personal cost. To be a United States citizen is fundamentally to have abandoned the nation as an organizing principle.

The United States is not just not a nation, it is a country that, by its very nature, actively rejects the nation as a form, at least for itself (again, obligatory caveat that I am not saying nation-states are bad – some of my best friends are nation-states! – merely that the United States rejects being one itself).

What is the United States?

The United States is thus quite an oddity (though again, not necessarily unique, just odd). It is not a nation-state, nor is it a multi-national state, but rather a de-nationalized state. It is the un-nation. This is not to say America lacks a culture (as is sometimes oddly asserted); indeed, it has quite a few with wonderful regional variations which unfortunately include South Carolinian mustard-based BBQ but fortunately also include all of the other forms of BBQ. And of course the mass-marketing of culture and particularly of education has created a shared ‘national’ literary, entertainment and consumer culture, though in many cases these are part of an emerging globalized consumer culture.

Instead, with no national core, it is the legally defined identity, citizenship, which forms the core of the United States. In this, the US has something in common with the Romans whose core identity, as we’ve been seeing (and will continue to see) was heavily dependent on citizenship as the key identity-marker over other ethnic, religious and cultural signifiers.

One may fairly ask why all of this haggling about definitions matters. But this brings us back to the mistake at the beginning: mistaking the metonym of calling the United States a ‘nation’ for the reality of it. Attempting to make policy on the assumption that the United States is a nation begins with a category error; the carpenter does not know that he is sitting in front of loom; attempting to whittle the weft will not produce results. Take for instance the idea of ‘national unity,’ a phrase which gets used and in the broad sense is useful but of course in the narrow sense relies on the same metonym as every use of ‘nation’ to refer to the United States. Consequently, attempting to foster unity through the nation (as a concept) is a hopeless effort because the unity was never ‘national’ in a real sense to begin with. After all, what shared history, shared myth of origin will you draw upon that all Americans will find valid and applicable to them? I will leave it to you to spot the politico-historical projects which have foundered on these grounds, but they are many. Because of course what you could actually have is civic unity, a different thing with different causes which connects to the one shared identity, citizenship rather than a shared past.

But an appeal to the nation for unity is always going to leave quite a lot of American citizens – perhaps even most of them – cold. Try calling Americans to war to fight for the ‘bones of their ancestors’ and you see the problem immediately: whose bones? Which ancestors? Buried where? Different Americans will give very difference answers to those questions! But call Americans to war because “your fellow citizens were attacked” and the response is real and emotive. I’ve always suspected this is the same reason for the particular centrality of the United States’ founding documents; we do not all have the founding itself in common, but we do have the Declaration, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights in common because those documents are understood to apply to citizens, regardless of where they fit in one’s ancestry and to guide the country as it exists now (this is presumably why the Articles of Confederation, no less historic, do not inspire the same patriotic feelings).

Worse yet is the idea that what the United States really needs is a national project, the sort of ‘nation building’ which transformed the fragmented states of Europe into a series of nation-states, to forge a national Blut und Boden (‘blood and soil’) identity out of United States citizens. It cannot be done; one may as well attempt to throw a pot from a bag of granite rocks, the raw material is wrong. Efforts to try to build this kind of national identity run aground on the same problem: whatever distant common history or myth of common origin one selects as the foundation for this kind of national project inevitably won’t be shared or understood in the same way by others, either because their ancestors weren’t here for that moment or found themselves on the unpleasant business end of it. This is not to say that Americans are immune to bad ideological projects, or that all national projects are necessarily bad (though some very much are), merely that the effort to form a nation generally fails because the basic ingredients are wrong. The necessary binding agent has been actively removed, though that hasn’t stopped regular efforts to replace it with crude populism and xenophobia. In a way, one may feel pity for the born-American who emotively longs for the comfort of the nation because it is something they cannot have, but then there ought to be a country for the people who would rather not be in a nation and here it is.

None of which is to say, as I have seen said, that the lack of a national consciousness weakens the United States, or represents some sort of flaw or failing. There are many ways to build a people; nationalism is only one of them and not necessarily the best. As we’ve been discussing, by the first century relatively few Romans could connect to a Roman ethnic or national identity (Livy overflows with alternate Italic identities rooted in different origins and ‘common’ (to them and not the Romans) histories; on that see P. Erdkamp, “Polybius and Livy on the Allies in the Roman Army” in The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476) eds. L. de Blois and E. Lo Cascio (2007). What is clear is that by Livy’s day there was a fairly vibrant literature stressing the heroics of allied contingents in the Roman army, distinguished by their then non-Roman identity, and although such narratives may have had at best a thin relationship with actual events, they speak to the alternative identities newly enfranchised Italians might have held to. That disconnect would only grow greater in the centuries to follow as Roman citizenship spread out of Italy and embraced people who truly had no connection to Rome as a place or the Romans as an ethnic group, but rather connected to the Roman polity as a citizen. Common origin wasn’t the glue that held the Romans together, common citizenship was, collective belonging to a polity which did not require shared ancestry or history.

(As an aside, I suspect this is the reason for another thing Rome and the United States share in common: multiple-choice foundation myths. For a Roman, Aeneas, Romulus, Ti. Tatius, Numa Pompilius, Servius Tullius, and L. Junius Brutus were all options for different sorts of ‘founder figures’ accomplishing different sorts of foundations. A Roman who didn’t much like the (patrician) story of Lucretia could emphasize the (plebian) story of Verginia to much the same effect. C. Mucius Scaevola (a youth, presumably unpropertied given that he is given a land-grant, Liv. 2.13) and P. Horatius Cocles (a patrician) and Cloelia (a patrician woman) provide in rapid series a set of alternative heroes; pick the one you like! Likewise, Americans have shifted emphasis from one framer, hero or founder figure to another; the multiplicity of framers makes it fairly easy, for instance, for Adams and Hamilton’s to come to more prominence lately as compared to say, Jefferson and Madison. Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr. share the National Mall with George Washington; pick your monument and the moment of foundation that fills you most with that pride of citizenship. Again, not one common history, but a collection of histories connected to citizenship and the country.)

Successful efforts to actually unify Americans are thus likely to focus not on national identity (which we do not share) but on citizen identity, which we do and which lends itself to many other shared things: an attachment to the country’s laws and stated principles, the documents which set out those principles, the institutions we maintain together and on the community of interest that shared ownership of a polity create. Those unifying projects, in turn, can only succeed to the extent that citizenship really is held in common; it falters when the citizenship of some Americans is (or feels) only second-rate. But citizenship over nationality has its advantages; the nation is an exclusive identity, but citizenship co-exists more easily with other identities – a necessary advantage in a country as preposterously diverse as the United States. And the emphasis on the citizen body over the nation is clearly a factor in the United States’ exceptional ability to embrace large numbers of immigrants successfully.

And so my country isn’t a nation, but a collection of citizens drawn from all of the nations, setting aside those national identities; a family of choice, rather than a family of blood, united by common ideals rather than common soil. We haven’t always lived up fully to that high ideal. Sometimes the siren call of the nation haws pulled us down away from it. But the ideal and the republic built around it remains. And that is what I will be celebrating come July 4th.

Typos:

“A ‘county’ is a territory and its associated polity; some countries are not states at all”

Did you mean county or country there?

“Bearing Ice Bridge” -> ‘Bering Ice Bridge”

The frivolous connections part of my brain is reminded of “The Flag” by Russell Baker, collected in “So This Is Depravity”, where he talks about fatherlands vs. motherlands and the recency of the idea of a “country.”

Can’t find a good version on the Web, but you can see part of it here.

On a similar note:

‘this, I suspect is one region (reason?) they tend to be so fragile’

‘a nation-state is when the boundaries and (of?) the nation and the state mostly coincide’

‘There is no single dominant American story, but a collection of American stories, none of which can claim primary (primacy?)…’

Fantastic essay as always. I look forward to these every week.

Fixed!

I wanted to comment on one way I think my experience, growing up as a white person in the 90s in the US whose immigrant ancestors are many generations back, differs from what you described here. And all the same caveats about this being purely descriptive rather than an attempt to pass judgment on what I’m describing. (I *do* judge it, but I’m trying to keep it out of this post).

Obviously, you are correct, that by the definition you give of nation, very few Americans can claim part of any nationality–pretty much just natives and recent immigrants who haven’t discarded the national identity of their former home, and in neither case is the nationality “American”. However, growing up, I experienced a very blunt attempt at a constructed pseudo-national identity for Americans whose ancestors were colonists or immigrants. The myth I was told, often and repeatedly, was that while America isn’t a “family” of blood and shared birth, it’s a family of choice and adoption. When your ancestor moved to America, they chose to join the American family, and the Americans already there adopted them into it. (Obviously, this view on American history doesn’t hold up very well to historical scrutiny, but you rightfully point out that national identities rarely do). The American national identity, as it was taught to me growing up, wasn’t an attempt to pretend we had a shared ancestry. It was a conscious, blunt attempt to reinforce the notion that ancestry is irrelevant. Once America adopts you, you’re American. Or so the national myth goes.

It’s not a nation by your definition, but it is a constructed shared identity other than citizenship. Even in this pseudo-nation, the US isn’t a pseudo-nation-state, of course, because slaves, natives, and their descendants can’t ever be included in this shared origin story (because it was never designed to include them, and was probably *intentionally* designed to exclude them). But I think it’s worth mentioning that to many Americans, reading this essay, their first thought would be something like “Well, of course we aren’t a European-style nation. We do things differently here. Birth just isn’t an important link to us, compared to the shared ancestral experience of immigration. We don’t fit your definition of national expression because your definition is too narrow.” And I don’t think that thought is entirely wrong, because there is a nation-like constructed American identity (again, intentionally constructed to exclude natives and slaves). And naturalized citizenship is often used as the marker of when an immigrant transitions from outsider to a member of this constructed group, but I don’t think it’s because it’s synonymous with citizenship.

While I agree that slaves and natives weren’t included in this constructed identity, I don’t agree that their descendants can’t be. For starters, it’s not true in practice–plenty of black and native people identify with the American nation. But also, why would past inclusion preclude present inclusion? The Chinese were excluded from US citizenship for a long time, but I don’t think you could claim the offer isn’t open to the Chinese.

I meant that the origin story–of an adopted family, which your ancestors joined by choice and were willingly welcomed into–just falls apart on its face when your ancestors were conquered or enslaved. It falls apart for many immigrants (Irish, Italians, Chinese come to mind readily) with a bit more effort, but the lie isn’t as obvious and is usually papered over. And again, I’m not talking about citizenship. I’m talking about a pseudo-national origin story, which was beaten into my head over and over in my schooling, but excludes vast swaths of modern Americans. Think of all the times politicians talk about the US as “a nation of immigrants”, as a quick example of this.

It’s definitely NOT the only American identity, and I think the extent to which my schooling emphasized this story as *the* American story is a strong condemnation of it. I was just challenging the notion that there aren’t constructed identities based around partially-true origin myths in the US. There is at least one.

Sure it works. Just took longer.

I think that’s exactly the point. Yes, we have a unifying identity (and sure, citizenship may not be the best border for it), but that identity is fundamentally different from the “your people have lived here for generations” identity that a “proper” nation uses. We see ourselves as a group of people that chose to leave behind our previous national identity and adopt a new identity instead. And since a conventional national identity isn’t something you choose, the new identity has to be something different.

That begs the question.

How does the US model of statehood compare to other states in the americas? I’d imagine there’d be some similarity between states with a settler colonialism based history.

This question would have fit better in The Queen’s Latin. Recently, I’ve been watching a youtube channel called Historia Civilis (https://www.youtube.com/c/HistoriaCivilis/featured) going through mostly Roman History topics. And I wonder if anyone here has thoughts on how reliable the information presented is.

I really enjoyed this piece. It really sets out some distinctions that are not well understood, neither in America nor outside. I find Americans are often unaware that nation-states (like my own Netherlands) work in different ways to their own country, commanding different loyalties and appealing to different feelings. Equally countries like my own struggle to try and super-impose a civic identity (necessary as people with non-Dutch ethnicity become a bigger share of the population) on a nation-state without thinking through these distinctions properly. Partly this is a issue of confused definitions: – ‘Nederlander’, (‘Dutch person’) is simultaneously the ordinary term for a citizen of the Dutch state, and for a person of Dutch ethnicity (because in around 75% of cases those are the same, and until quite recently in more than 90%). As a result attempts at integration here tend to waver between trying to construct a plausible civic identity to adhere to (good idea but a lot of work) and trying to drive integration into the Dutch *ethnicity* (not such a good idea, not in fact possible on many definitions)

I can’t speak to other states – but I think you’ve profoundly misunderstood the meaning of nationality as it’s normally used in the UK with this comment:

> none of the constituent countries of the UK is below 75% its core ethnic identity.

The first point is that this is simply not true in Northern Ireland. “British” is the most common identity there, even counting those with overlapping identities, it makes up less than half of the population (or did at the last census. That’s likely to have changed dramatically since then.

The second thing, and I think it’s a more major issue, rather than simply nit picking about forgetting one of the UK’s constituent countries, is that “English” in common usage in the UK is much more equivalent to “American” than it is to Irish-American, or French-American, or basically any American hyphenated identity. My wife was born in England, to Welsh parents, who’s own parents are Scottish and Irish. She identifies solely as Welsh, and when she lived in Wales, would have made up part of that 75% Welsh. This kind of complex identity is, ime, super common in England, and based on the social institutions which often mirror NI’s split, likely similarly so in Scotland. So the 75% figure here isn’t really comparing like for like.

The third thing is that of course, even if you accept that “people identifying as Scottish” is equivalent, it still hides the massive national differences. North Walians will often introduce their ethnicity as being “English speaking North Walian” (or just North Walian, if they speak Welsh). Highlanders see themselves as quite separate from central belters, to the point of having radically different founding myths (around the clearances, and the famine primarily). The north of England is culturally quite distinct from the south, which is in itself bifurcated in a variety of ways around very complex identities, which often don’t share a language, or a founding myth. The Afrocarribean population of Bristol has a very different take on the founding myth of the empire, than the White British population of a former weaving town. And fundamentally, for most European states, none of this is exceptional. Brittany, Corsica, Catalonia, and the Basque Country have their own languages in France. South Tyrol is mostly German speaking in Italy. Spain is a complicated enough mess that it’d be difficult to claim anything about.

With the definition of “nation state” you seem to be using, I’m not sure anywhere in Western Europe larger than *maybe* the Netherlands would qualify (and I strongly suspect that I’ve just missed a bunch of national differences within the Netherlands).

A more likely, and useful definition of a nation state is a state where when you ask people “what country are you from?”, the state’s name pops up almost all the time. That would likely exclude the UK, but *include* the USA.

There are indeed sub-national differences even within the Netherlands, which offer a microcosm of how this usually works in European countres:

The ‘autochtonous’ population of post of the sea-facing original provinces of the Dutch revolt (Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Groningen, Gelderland tend to regard themselves as Dutch in an uncomplicated way, and speak more or less classic Dutch at home. Together this represents a majority of the population.

The districts on the German border speak dialect forms that are not classic Dutch at home but otherwise tend to consider themselves Dutch (to the extreme frustration of the Germans anno 1940-45).

The inhabitants of Brabant in the south think of themselves as having a variant culture from the Dutch core (pure Catholicism, better food, different accent) but would certainly not consider independence.

A combination of the above two categories is found in Limburg, where they have southern traditions and speak a dialect that is technically closer to Charlemagne’s Frankish than to Hollander Dutch.

Finally there’s the Frisians, whose language is explicitly recognised as a official one, but whose traditions (especially around skating and sailing) blend into the Dutch core.

So yes, even the Dutch are not monolithic, small though the country is. This is one of the areas of profound misunderstandings between Europeans and Americans. Europeans are defined by their ethnicity and often their region, and I am pretty sure that they move around less. The majority of people of my village would identify as Dutch abroad but are lifelong North Hollanders and that forms an important of their identity in itself, and is equally rooted in the kind of Blut and Boden story Bret covers in his piece. This is rarer in the US (though of course not unknown – c.f. New Yorkers, Southerners, Texans etc)

You, like a lot of people on the internet, overrate the importance of the regional languages in France, especially in Brittany. It’s in no way similar to South Tyrol or the Spanish Basque Country and Catalonia.

A separate Frisian identity is very strong in the Netherlands.

That said, nothing solidifies a sense of national identity like foreign occupation. The French would refer to the “Goddons” during the Hundred Years’ War (English soldiers who would clearly swear often enough for it to become their nickname), and of course the Irish.

The existence of sub-national populations is kind of precisely the *point* of nationalism as a concept, & why it had to be so aggressively inculcated even in *Europe* in the 18th-19th centuries.

Nationalism proper has *always and everywhere* been a myth, and part of a propaganda campaign imposed by & to the benefit of a centralizing elite. It wasn’t Languedoc or the Landes that benefited from Parisian insistence on a national identity, any more than Catalonia benefits from a Madrid-centric Spanish identity today. The few exceptions where this concept of nationalism might actually be somewhat plausible are the fragmentary post-Wilsonian states in the Balkans emerging from the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, or post-colonial states outside Europe more generally; and not for nothing do they tend to be tiny, highly fragmented, and extremely prone to carrying out genocides. (It turns out “self-determination” based on ethnic identity was a terrible idea, when it wasn’t just outright ignored in favor of continued colonization.)

But I don’t think that’s what Dr. Devereaux is saying here. It was all myth and flim-flam, but there absolutely was a concerted effort in Europe for two centuries to reconcile power structure with particular ethno-cultural identities. (And, when the existing power structures governed enough territory to include diverse peoples, this included campaigns to force the people to conform to a particular cultural identity and to downplay ethnic and linguistic differences). Did it work–well, yes and no; but this article says that there is absolutely no plausible way in which it ever could work in the USA. “Nos ancêtres les Gaulois” is hogwash in France, but you could go along with it to get along with it, or even buy into it if you weren’t attached to your regional culture; but it’s completely unsupportable in the States.

…except that, unfortunately, it *isn’t* completely unsupportable; the US has historically just done it more subtly. Our curriculums have tended to forego an explicit appeal to an ethnic identity in favor of a completely Eurocentric (really Anglocentric) cultural-historical identity. You can have a classroom full of kids whose most recent ancestry is Germany or Poland or South Asia or who were enslaved and brought to this country by force, and they’ll still be taught all about the Mayflower Compact and the House of Burgesses, and maybe the Roman/Classical origins of American democracy but never a whit about the influence it took from the Iroquois Confederacy, etc. You *don’t have to tell them* that they have a common ethnic identity, because they obviously don’t; you just have to tell them that the only history that matters is that of the English settlers, and then deny them the opportunity to learn about or express anything else.

And what’s happening in American politics today–apart from class/wealth inequality getting so bad as to be unsustainable, which is ratcheting up tensions all around–is that the kids in that classroom who knew they didn’t see themselves in the history lesson now (thanks to the Internet) finally have avenues to learn about and voice identities that are more plausible for them, and the kids who *could* and *did* imagine themselves as the privileged actors in that history (however inaccurately) are deeply threatened at the political power of increasingly-organized groups who actively reject that identity.

This seems to me to go much too far. Nationalism worked because there was and is *something* there, it’s not all ‘myth and flim-flam’. As is referred to elsewhere in this thread, the French and the English and the Bohemians etc were seen as ‘nations’ in 12th century Paris, well before the rise of any concept of nationalism. The ‘German people’ were being addressed by pamphleteers in the 16th century. Of course these ‘nations’ were nothing like as immutable and precisely defined as later nationalists pretended, but they clearly existed before elite mythmakers got to work. In particular people have always found it easier to see commonality in those who speak the same language, and having the same language plus living in close proximity very often leads to people to develop a lo of alignment on cultural habits etc

An English nation would have been myth and flim-flam in 12th century Paris; England and the English were a cobbled-together mashup of Celts and whatever other pre-Roman peoples, Romans from wherever, Saxons, Danes, and French.

But of the cobbled mashup was real, then the nation was real.

The main reason we don’t learn about the influence American democracy took from the Haudenosaunee League is that it probably didn’t take any. American democracy follows pretty standard Anglo common law form, while the Haudenosaunee Great Law of Peace is radically different, and crucially, not democratic. Chiefs vote, not every male, and chiefs are exclusively chosen by the elder women of matrilineages, not every female.

But don’t take it from me: take it from the collection of sources gathered at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iroquois#Influence_on_the_United_States, and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Law_of_Peace#Influence_on_the_United_States_Constitution.

Though it should be noted that neither did the US at the adoption of the Constitution (though there was a radical movement towards at least allowing male white citizens to vote) and there is of course the Senate. (which at the time was appointed by local elites, not by election)

As an American, I’m simply baffled by the lack of unity in the UK, and in Europe in general. How can you live that close together for that long and maintain separate ‘nations’? Heck, how can you maintain separate accents? We’re much bigger, and all our accents are already mushing together – and when it comes to marriage it seems less than 50% chance of any given couple born in the same town or city as each other.

I can just about understand separation from people who don’t speak the same language as you do, or when you need a passport to travel, but that’s all that makes sense to me.

Maybe it just illustrates Bret’s point, that the formal definition of ‘nation’ is so removed from everyday life here that I can’t imagine it being important.

TV is mushing American accents together, but maybe it happens more here because our accents were more similar to begin with.

Those accents formed way back when no one ever traveled more than 5 villages from their burthplace. Often those same accents are fading as a direct result of modern mobiliity and mass culture.

America is too young for individual accents to drift far away from one another.

Fun linguistics time! American accents are not mushing together, by any metric. They are, in fact, diverging, as all these things do. Also, I’m going to call them “dialects”, because I feel that’s more accurate; it’s not just sounds, but word choice and grammar that are divergent.

Most of the perception of mushing is based on sociolinguistic factors; a great example is that for much of the 20th century Pennsylvania was a net exporter of people to Western states, making Pennsylvania dialects widespread. For radio and then film and TV, people with non-prestige accents are less likely to be selected for nationally broadcast content; this is one of the causes of the notable drift between “old timey radio” dialects and the present Prestige Midlands, and it’s also why locally produced content is almost always strongly marked. And Americans are no more likely to move than anybody from any other place (it’s college graduates that leave home to join the mobile professional class) so dialects start to diverge, while the people speaking them fail to notice until somebody from somewhere else shows up and says “buggy” and can’t distinguish “pen” and “pin” in speech (that’s me).

For my background, I have lived in Southern California, Central Maryland, Central and Northwest Arkansas, and Southern Wisconsin; I have noticed zero mushing, and quite a bit of difference. I have my mother’s Ohio/West Virginia Allegheny dialect, and my father’s Ozarks PEN-PIN merger (one of the things he never learned to hide). I use structures like “needs washed”, but not structures like “should’ve went”. I never sounded like my peers in Maryland, and I don’t sound like people here in Wisconsin. And crucially, I’m not old; I’m 35 as I’m writing this, and I know local Wisconsin 20 year olds who sound like 55 year old Wisconsinites.

As to why there are so few American dialects: there’s not. There’s plenty. There’s always been plenty. They’ve shifted and changed. As mentioned, the country is so big and people usually hear so few in their lifetimes that for the most part, they don’t know there are differences. I’d wager plenty of Americans would guess a Yat speaker was from New York, and would be shocked to learn it’s a New Orleans dialect. The Tidewater is the stereotypical “southern”, but very few Southern dialects sound anything like it. The Northern Cities is a collection of dialects that can sound alike, but don’t always, and crucially often sound distinct from dialects in the rural parts of their states. And there’s more examples, but this comment is already super long.

No harm in the pin/pen crap.

I don’t distinguish them either. If you need the sounds to tell the two apart and can’t determine that from context, that’s not my problem, friend! Nobody seems to care much that I say him/hem the same.

People tell me all the time that I “don’t have an accent” because I’m using my old retail voice with them, but they aren’t around when I’m at home, reading these comments with my girlfriend, and saying shit like “madd’r’na wet hen”!

I don’t have a knowledgeable answer to give, but…

Something you see here (UK) more frequently than assertion of who you are is joking about who everyone else is.

I’m Welsh. Everybody around me would say they were Welsh. But we’d struggle to tell you what being Welsh is! Ask us about the Scots, though, and we’ll have a dozen jokes to hand about their drinking, their drugs, their general disorderliness — notice a lot of things jumped to my mind?

And ask the Scotsman who the Welsh are and he’ll bring up leeks, sheep, rain, sheep, and probably sheep.

This isn’t to say we define ourselves by who we’re not. But the fences around you may be propped up by people on both sides, for the pleasure of having a fence as much as anything else. The fences may be somewhat (though never entirely) artificial; they may on a technical level be meaningless. But the fences may help you to preserve things which you want to preserve like language, accent and culture. And so perhaps everybody holds them up. After all, the fences are only waist-high.

Which is to say that ‘separation’ of a people doesn’t just occur because you can’t physically get to someone. It may occur because, well, whatever being Welsh is, whatever being a Scot is, they’re the better for being their own things and everybody knows it. You don’t even have to shove the other person away. You just have to pull them close to you and make a joke at their expense.

You do maintain a different identity in the US to, say, Canada and Brazil. It is not size that matter, but perceived identity.

A very interesting read, thanks! Puts into words some things I’ve intuitively felt for a while. Despite being Nebraskan-born I spent basically the first half of my childhood outside the US, which puts me in a strange position where I both have ancestors who were on the Mayflower and yet associate more closely in some ways with first-generation immigrants. And I thus strongly resonate with that notion of American identity being primarily about *citizenship* rather than *nationality*.

Quick question: Mr. Devereaux, would you say that the Southern secession was an attempt at establishing a national identity? Had they succeeded, there might have been a national (trans-state) Dixie identity shared between the white population, with the dual founding myth of the supposed English or Scot-Irish origins and of having rebelled against federal government. (And given the status of black folks and the military adventurism in Latin America, a good chance of ending up as an imperial nation-state.) Of course, the North won in the end, so as time passed the Dixie identity became a regional quirk, although even in this form the spectre of abortive nation-building loomed for a good few decades, perhaps over a century.

The Creoles and Tejanos would probably end up as “these odd fellows who we still consider ours even when they try too hard to be different”. The Cherokee, I don’t know.

One wonders if this trans-state identity would trump the state identities. (I wager it would, given enough time.)

I think Southern secession is best understood not as a national project, but as a slaver’s rebellion – it wasn’t oriented around a regional cultural identity, but defending a specific terrible institution.

As I understand it, the elites attempted to manufacture a regional cultural identity during the war, but it didn’t stick until afterward. Speaking as a Southerner myself, the regional identity certainly exists now.

There was actually a concerted effort among pro-slavery radicals in the years leading up to the secession crisis to fashion a kind of “southern nation” distinct from the rest of the United States.

Seems strange to declare that Russia is an empire because it has captive nations like Chechnya, but the United States isn’t, even though the US also has captive nations like the Cherokee.

Is he distinguishing based upon how much internal nations have self-government and can police themselves?

A difference based on how much self-government and self-policing is permitted?

The Cherokee are full citizens, though, and not violently quashed (at least, not in the last century and change).

Calling the US an empire in the 19th century would’ve been pretty fair.

Chechens are full Russian citizens (as are Dagestani, Bashkir, Tatar, Chutki and many other ethnicities).

If anything Russian minorities could be said to have more strength and autonomy, which is how the Chechens could even maintain a major war against the Russian Army. The Cherokee simply *couldn’t*, could they? They are too dispersed and too reduced in numbers.

(none of this is to excuse the appalling treatment of the Chechens, I just don’t think the war against them is the differentiator between ’empire’ and something else. I buy Bret’s argument that the real difference between the USA and Russia is that Russia has a core of ethnic Russians whose history and historical mythology help define the nature of the state as ‘Russians and the people conquered by Russians’, whereas America lacks this)

Russias constitutent republics are russian citizens, though.

Part of the issue may be demographic. If we count the Native Americans as captive nations (an argument with considerable merit), the fact remains that they make up a very small percentage of the United States’ population and have been driven off all but a tiny fraction of its territory.

Russia’s territorially concentrated ethnic minorities (the ones that can reasonably claim to be a “nation” but not part of a Russian nation) make up a relatively larger proportion, as I understand it. And while that percentage is still not large, this is due mainly to the massive amount of peripheral territory Russia lost in the breakup of the USSR, only about a generation ago.

Gonna second what Cian said — from an outside perspective (German/European) I feel like your definition of “nation” is pretty disconnected from how people actually talk about it. It’s true that at their core, nascent European nationalisms defined themselves largely through “blood and soil”, but I think post-war conceptions of the nation in Europe have changed to be centred around *institutions* and their attendant myths — the political history of states, national football teams, a vague set of democratic values. The impression I am getting from over here is that the vast majority of Americans define their identity as “American” in a similar way. The national foundation myth of America seems to be more open than you describe — from my perspective, it seems to include not just the grand spectacle of state formation (from the Pilgrims to the Constitution, so to speak) but also mythologised events/processes like the experience of American slavery, Wounded Knee, immigration and integration as embodied by the ideal of the American Dream, WW2, the Civil Rights movement, 9/11 and so on. It’s a pick-and-choose approach to national foundation myths (as you rightly point out), but that doesn’t seem to actually change the nature of the resultant identity to be *not* a nation.

I assume the problem with the pick and choose myths is that, at that point, you don’t really end up with one nation so much as several. While some variation in the national mythology is compatible with it lending itself to one coherent nation, after a point, you just have multiple distinct mythologies, and distinct nations associated with them.

Similarly, the problem with the mythologized events or processes you mention is probably that different US citizens likely bring such different perspectives to them that they can’t form the same national mythology for everyone.

We have massive similar problems over here in the UK, although we’re much more likely culturally to brush them under the carpet. Part of our British identity it is a tendency towards “live and let live” and not think too deeply about our conflicted cultural, ethnic, political, and civic identities. It is also why Brexit and the Scottish independence issues have been so traumatic. Although, thinking about it, maybe I have an English bias here!

Although the UK is a multi-national state, we do have the problem of an overweening dominant English polity. This can lead to semi-conscious equation of “British” and “English” within England. In fact, our problematic question is “who are the English”, I think. While “white English” people have common national myths, there are obvious tensions in a multi-cultural society, if this is imposed on those on the wrong side of “white English” history.

This was exacerbated by the introduction of things like our National Curriculum, particularly in history – more the concept of “National” than the actual content, which I think is broadly sensitive to lots of the issues. The Tudors and Stuarts are not really relevant to our non-white citizens, I fear, but recent Conservative governments have been insistent on an emphasis on “British history”, quite a lot of which actually seems to mean English (as the dominant nation historically). There was a particular problem when the government tried to push forward some form of commonly-held “British values”, which were derided and ignored by much of the populace. Our commonly-held views of British citizenship are malleable, subtle in their different emphases in different communities, and actually do form the foundations of civic society over here. However, part of those values is a tendency to deride attempts to define them explicitly, because that draws unnecessary boundaries around them, and therefore might exclude some groups.

I suspect that the best way to identify the “English” is to ask them which international football team they support. The “British” on the other hand will support a very wide variety of teams, many of them not within the United Kingdom.

The Tudors and Stuarts are relevant to non-white citizens because they contributed to the development of the constitution they now live under.

While this is true, if the goal was to understand the evolution of the British constitution, I’d say UK schools would be spending significantly more time studying the Irish question…

English ideas of British history being primarily English are, I think at least partly a result of education being a devolved matter. Welsh, Scottish, and Northern Irish schools have their own curriculums, and thus have less interest in what’s thought in England (and thus less interest).

Although it’s obviously a little odd, given that this was all carried out under Gove, who identifies as Scottish (albeit serving an English constituency).

Quite an enjoyable and informative read. Kudos to you for writing and sharing it.

I do have a question: would the Mormons qualify as a nation, not just because of their founding & subsequent history, but also because they at one point had territorial borders which, like Texas, were modified to join the United States?

Ah, Bret. This deracinated South Carolinian sees your barbeque fightin’ words!

Real question: If you actually dislike mustard barbeque, is it because it’s simply a departure from what is generally considered barbeque by the country at large (see: what makes up the preponderance of sauces at any given grocery store, even in SC), is it because you’re not a fan of mustard, or something else?

As a S. Carolinian and Germanophile, pork and mustard are a classic pairing and though I didn’t much like it early on in my life, it’s my favorite style now.

I am not generally a fan of mustard so that is probably the issue. Also it was the last form of BBQ I think I was exposed to.

Thanks for introducing me to this delicious-sounding sauce. I’m going to try it on my next veggie burger. And I enjoyed your article, as always!

I went to Yellowstone last week, and I had “BBQ” there that consisted of beef cut into strips that looked like bacon, with no sauce. It was good, but it seems to me it was no more BBQ than steak is BBQ.

Isn’t there an identifiable border based on if unmodified “barbecue” means pork or beef?

If so, it’s somewhere west of Georgia and Ohio, and east of Texas and Wyoming.

I do not think that shifting between technical and vernacular use of the term nation makes a good argument. Also this assumes that whether a country has one given myth of origin is not just an accident to its commonality.

Very interesting, thank you! This puts my own country (Canada) into perspective quite nicely as a lot of the concepts here I think would map onto our own polity.

In Canada we’ve had a debate over whether Quebec is a nation, with federal politicians alternatively trying to win favour in Quebec or upset at what they see as fostering divisiveness.

The Quebecois can potentially lay claim to some of the principles of a nation you’ve laid out but are still a settled population- i.e. they’ve existed in the territory for a long time, can trace their ancestry to a single population (only 2600!), and have a distinct language and ethnicity.

Of course it gets messy and invoking Quebecois nationalism can be quite exclusionary (what about recent francophone immigrants for example). But it could arguably count as a nation within the settler population of North America.

That is probably fair, but would you have to restrict the relevant territory to Lower Canada? Certainly I would think it would exclude Northern Quebec, and especially Nunavik.

Something else I noticed is that if you consider Canada’s treatment of the North (extraction of resources for the sole benefit of southern Canada, historically reduced power and constitutional position of Territorial governments, subjugation of almost the entire population of the region (since few people lived there who are not Inuit)), Canada looks more expressly imperial than the US. That may have been remedied somewhat by the creation of Nunavut and special governance agreements in Inuvialuit, Nunavik and Nunatsiavut, but I don’t know those arrangements well enough to know if they have solved the problems, either of self-government or of resource extraction disproportionately benefitting the South.

‘I can’t speak to the classical usage, but ‘natio’ in medieval usage did not map to a political structure (presumably because most polities were formally dynastic). For instance, the University of Paris had ‘nations’ of French, Normans, Picards, English and Alamannian; Prague had Bohemian, Bavarian, Saxon and Polish. It seems to have meant roughly ‘the region where one was born’.

a family of choice, rather than a family of blood

I hope it doesn’t come across as terribly self-centered if I just offer some perspective on that from the sister republic. (Happy birthday, big sis!)

In Swiss discourse, the idea of a nation based on linguistic unity is generally rejected, not only because it is not applicable, but also because it is seen as a threat to the existence of Switzerland itself, even after irredentist nationalism is no longer prevalent in the neighbouring nation-states. Instead of rejecting the idea of a nation wholesale, however, it is redefined in a somewhat constructivist way as existing through the shared will of the citizens to be a nation, despite lacking certain characteristics (like a common language) that other nations might see as fundamental to their identity. Now maybe that’s just semantics; a citizen-state desperately trying to misapply the notion of the nation-state to itself in order to defend its legitimacy among stronger (and at times rather aggressive) nation-states in its immediate vicinity; a predicament that the United States do not share. Or maybe it’s a nation that is just more transparent than others about the fact that it is a fiction – a useful fiction serving to uphold political institutions that are generally regarded as beneficial by the people sharing in them.

Though even allowing for less essentialist definitions of nationhood, the diversity in the US is still way larger than in nations with a high internal diversity, so the attempt to forge that diversity into a Willensnation may indeed be futile. Let’s just hope that political institutions alone are sufficient to inspire the loyalty they need in times of crisis even without the underpinning of a shared identity, fictitious and constructed as it may be.

I would guess Switzerland is an example of what Bret called a multi-national state. But since it’s origin story goes back to medieval times, maybe it should be called a multiethnical nation.

Switzerland is, as Mr. Devereaux says, a multinational state, not a “non-national” state. It has four different nations (well, three nations and a mini-nation) that make it up. Same for a place like India or Nigeria, really.

I like this in general, but I have one quibble – you referred to slave importing from 1619 to 1860. The US banned the import of slaves in 1808. It seems like a few were smuggled thereafter, but not many, and like it had basically ended by around 1820. After that, it was natural growth of the population(well, as “natural” as it can be when a lot of the children came from prolific rape) that supplied the slave markets.

I’m not sure ‘a few, not many’ was any comfort to those few. Comment seems accurate to me.

Obviously not. But if “a few” is your standard, your end date needs to be 2021.

It was brought up in the context of how modern black Americans think of their ancestry. Rare exceptions tend not to factor into stories that large-scale very much.

If we’re including a few smuggled slaves, than we shouldn’t pretend importation ended in 1860 either, since human trafficking and clandestine slavery continues in the US to this day, as it does in pretty much every country on Earth.

Americans tend to under-report British or English ancestry. If an American is of English and Italian ancestry, they will very likely self-report as Italian, because English ancestry tends to be “invisible.” It is no accident that in Utah, where many Mormons live, reports a high share of English ancestry, as Mormons tend to keep better track of their genealogies.

Then again, that could support your argument that America is not a nation, because Americans emphasize the more unique parts of their ancestry, rather than the British or English parts, which would be rather more common.

Yeah, a lot of misdirection is being risked by using the word “claim” rather than “have” in that sentence, which even links to the prominent and heavily-cited warning, “Demographers regard the reported number of English Americans as a serious undercount, as the index of inconsistency is high and many if not most Americans from English stock have a tendency to identify simply as “Americans” or if of mixed European ancestry, identify with a more recent and differentiated ethnic group.”

But even the sentence taken literally is still incorrect. I wouldn’t self-designate as “English” (at least 1/8 of my ancestry by geneology, maybe as much as 3/8), but to therefore state that people like me do not “claim British ancestry” is false. If people with primarily English ancestors don’t necessarily call themselves “English”, how much less likely is it for those of us with fractionally-English ancestry to do so?

The conclusion that “America is not a nation” in the genetic sense seems overwhelmingly correct, but this isn’t a good argument supporting it. Instead it’s instructive to add up the *other* categories; even in that truncated Wikipedia table you can see that a majority of Americans self-identify as something other than Irish/English/American/Scottish/Scots-Irish.

There’s also the practical problem that for any statement about “Americans’ ancestry” to be relevant to the discussion, all the slices of the pie chart need to add up to 100%. Insofar as you might (for instance) identify as being Irish-American and English-American and the Salvadorean-American descendant of a first-generation immigrant who married someone with those other two identities… Well, that tends to further dilute the degree to which you can identify with any specific ‘national’ narrative.

And there are plenty of people who aren’t reporting Irish or Italian ancestry from a few generations earlier, likewise.

Uh, my mom is Dominican-Cuban

My dad is from Chile and P.R. which means:

I’m Chile-Domini-Curican

But I always say I’m from Queens!

My emotional reaction to the title was What The Hell!! But once I read it I realized that Bret was saying what I already knew; American Identity is based on allegiance to our Founding ideals as laid out in our Founding documents. The similarity between the American Identity as citizens first and Roman citizenship hadn’t occured to me before but I can see it now.

I take a certain pride in being a typical American mongrel with ancestry from four continents. One grandfather was an immigrant, his wife the daughter of immigrants, the other grandfather’s family had been here since the 1860s and his wife’s ancestors since the late 1700s.

I think that one issue that you leave undiscussed here is the issue of ethnogenesis. I am sure that you know it played a great part in the formation of various nomadic peoples that troubled East Roman Empire in the Middle Ages: people changed their identities to conform with the successful tribe.

In the case of US, the stop of massive legal immigration in 1920 caused a bit similar process. The people born in 1920’s did, in fact, live in a country where most people were native citizens. They were taught the foundation myths, and these became their imagined past, even if they didn’t, strictly speaking, descend from those people. The white American of 1940’s and -50’s was actually living in the conceptual nation of other white Americans. The end of immigration allowed a real ethnogenesis. “Whiteness” as defined in the US today is actually not a phenotypic category but an ethnicity.

The ideal of shared citizenship is the only way to form a polity that takes into account all Americans. There is, however, an alternative way of looking at the issue: USA as an ethnic state of “real Americans”, i.e. white people with a couple of generations of American ancestors. For such a group, you can get the common ancestry and a mythic past (Europeans who emigrated to America in 16th to 19th centuries to escape oppressive governments and to find better life). If you claim that the USA is actually the ethnic nation state of such persons, you get very close to the current Republican agenda.

That is most definitely NOT the Republican agenda! Not as understood by this Republican!

Voting restrictions, keeping immigrants out, attempting to reduce powers of cities….yes, it very much is.

This is not the place for a debate on contemporary issues so I will just say I strongly disagree!

We’re judging by the actions the party is taking. Say you disagree all you want, this is clearly the diection Republicans are moving in.

You are listening to a tendentious version of republican ideas and actions put out by the opposition.

Republicans, recently, have: