This week we’re going to start tackling a complex and much debated question: ‘how bad was the fall of Rome (in the West)?’ This was the topic that won the vote among the patrons of the ACOUP Senate. The original questions here were ‘what caused the loss of state capacity during the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West’ and ‘how could science fiction better reflect such a collapse or massive change?’ By way of answer, I want to boil those questions down into something a bit more direct: how bad was the fall of Rome in the West?

At first I thought I would try to answer that in a single post but it rapidly became apparent that giving a sufficient answer was going to require multiple weeks: my plan is for three parts (I, II, III). In part I (this part), I want to focus on culture, literature, language and religion (‘words’). In part II, we’ll then turn to look at states and government (‘institutions’), though this will also entail looking at the institutional part of religion, for reasons that will become clear as we get there. Then finally in part III, we’ll turn to look at economics and demographics (‘things and people’), the concrete realia of people’s lives. In all of these, we will mostly be focused on the western empire (with some gestures at the East), but I’ll note here (and no doubt repeatedly subsequently) that this is because the empire didn’t fall in the East, at least not any time remotely around the fifth century. The continued existence of the Eastern Roman Empire is a free, massive point that the change-and-continuity argument gets to score at the beginning of these debates for free, every time.

As will readily be apparent, that significance of that division of topics will be important because this is one of those questions where what you see depends very much on where you look, with scholars engaging with different topics often coming to wildly divergent conclusions about the impact and experience of the fall of Rome. And there is no way to really discuss that divergence (and my own view of it) without diving into the still active debate and presenting the different scholarly views in a sort of duel. I’ll be providing my own judgements, of course, but I intend here to ‘steelman’ each argument, presenting it in what I view as its strongest form; as will some become evident, I think there is some truth to both of the two major current scholarly streams of thought here.

As always, if you like what you are reading here, please share it; if you really like it, you can support me on Patreon; members at the Patres et Matres Conscripti level get to vote on the topics for post-series like this one! And if you want updates whenever a new post appears, you can click below for email updates or follow me on twitter (@BretDevereaux) for updates as to new posts as well as my occasional ancient history, foreign policy or military history musings.

Two Knights an Old Man and a Nitwit

So who are our combatants? To understand this, we have to lay out a bit of the ‘history of the history’ – what is called historiography in technical parlance. Here I am also going to note the rather artificial but importance field distinction here between ancient (Mediterranean) history and medieval European history. As we’ll see, viewing this as the end of the Roman period gives quite a different impression than viewing it as the beginning of a new European Middle Ages. The two fields ‘connect’ in Late Antiquity (the term for this transitional period, broadly the 4th to 8th centuries), but most programs and publications are either ancient or medieval and where scholars hail from can lead to different (not bad, different) perspectives.

With that out of the way, the old view, that of Edward Gibbon (1737-1794) and indeed largely the view of the sources themselves, was that the disintegration of the western half of the Roman polity was an unmitigated catastrophe, a view that held largely unchallenged into the last century; Gibbon’s great work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1789) gives this school it’s name, ‘decline and fall.’ While I am going at points to gesture to Gibbon’s thinking, we’re not going to debate him; he is the ‘old man’ of our title. Gibbon himself largely exists only in historiographical footnotes1 and intellectual histories; he is not at this point seriously defended nor seriously attacked but discussed as the venerable, but now out of date, origin point for all of this bickering.

The real break with that view came with the work of Peter Brown, initially in his The World of Late Antiquity (1971) and more or less canonically in The Rise of Western Christendom (1st ed. 1996; 2nd ed. 2003, 3rd ed. 2013). The normal way to refer to the Peter Brown school of thought is ‘change and continuity’ (in contrast to the traditional ‘decline and fall’), though I rather like James O’Donnell’s description of it as the Reformation in late antique studies.

Among medievalists2 this reformed view, which focuses on continuity of culture and institutions from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages, remains essentially the orthodoxy, to the point that, for instance, the very recent (and quite excellent) The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe (2021) can present this vision as an uncomplicated fact, describing the “so-called Fall of Rome” and noting that “there was never a moment in the next thousand years in which at least one European or Mediterranean ruler didn’t claim political legitimacy through a credible connection to the empire of the Romans” and that “the idea that Rome “fell” on the other hand, relies upon a conception of homogeneity – of historical stasis…things changed. But things always change” (3-4, 12-3).3 As we’ll see, I don’t entirely disagree with those statements, but they are absolute to a degree that suggests there is no real challenge to the position. There have been a few cracks in this orthodoxy among medievalists, particularly the work of Robin Flemming (a revision, not a clear break, to be sure), to which we’ll return, but the cracks have been relatively few.

While some ancient historians also bought into this view, purchase there has always been uneven and seems, to me at least, now to be waning further. Instead, a process of what James O’Donnell describes as a ‘counter-reformation‘ (which he stoutly resists with his own The Ruin of the Roman Empire; O’Donnell is a declared reformer) is well underway, a response to the ‘change and continuity’ narrative which seeks to update and defend the notion that there really was a fall of Rome and that it really was quite bad actually. This is not, I should note, an effort to revive Gibbon per se; it does not typically accept his understanding of the cause of this decline (and often characterizes exactly what is declining differently). Nevertheless, this position too is sometimes termed the ‘decline and fall’ school. My own sense of the field is that while nearly all ancient historians will feel the need to concede at least some validity to the reformed ‘change and continuity’ vision, that the counter-reformation school is the majority view among ancient historians at this point (in a way that is particularly evident in overview treatments like textbooks or the Cambridge Ancient History (second edition)). We’ll meet many of the core works of this revised ‘decline and fall’ school as we go.

As O’Donnell noted in a 2005 review for the BMCR, the reformed4 school tends to be strongest in the study of the imperial east rather than the west (something that will make a lot of sense in a moment), and in religious and cultural history; the counter-reformation school is stronger in the west than the east and in military and political history, though as we’ll see, to that list must at this point now be added archaeology along with demographic and economic history, at which point the weight of fields tends to get more than a little lopsided.

Those are our two knights – the ‘change and continuity’ knight and the ‘decline and fall’ knight (and our old man Gibbon, long out of his dueling days). To this we must add the nitwit: a popular vision, held by functionally no modern scholars, which represents the Middle Ages in their entirety as a retreat from a position of progress during the Roman period which was only regained during the ‘Renaissance’ (generally represented as a distinct period from the Middle Ages) which then proceeded into the upward trajectory of the early modern period. Intellectually, this vision traces back to what Renaissance thinkers thought about themselves and their own disdain for ‘medieval’ scholastic thinking (that is, to be clear, the thinking of their older teachers), a late Medieval version of ‘this ain’t your daddy’s rock and roll!’

But almost every intellectual movement represents itself as a radical break with the past (including, amusingly, many of the scholastics! Let me tell you about Peter Abelard sometime); as historians we do not generally accept such claims uncritically at face value. For a long time, well into the 19th century, the Renaissance’s cultural cachet in Europe (and the cachet of the classical period where it drew its inspiration) shielded that Renaissance claim from critique; that patina now having worn thin, most scholars now reject it, positioning the Renaissance as a continuation (with variations on the theme) of the Middle Ages, a smooth transition rather than a hard break. At the same time, knowledge of developments within the Middle Ages have made the image of one unbroken ‘Dark Age’ untenable and made clear that the ‘upswing’ of the early modern period was already well underway in the later Middle Ages and in turn had its roots stretching even deeper into the period. It is also worth noting here, that the term ‘Dark Age’ has to do with the survival of evidence, not living conditions: the age was not dark because it was grim, it was dark because we cannot see it as clearly.

The popular version of this idea continues, however, to have a lot of sway in the popular conception of the Middle Ages, encouraged by popular culture that mistakes the excesses of the early modern period for ‘medieval’ superstition and exaggerates the poverty of the medieval period (itself essentialized to its worst elements despite being approximately a millennia long), all summed up in this graph:

While that sort of vision is not seriously debated by scholars, it needs to be addressed here too, in part because I suspect a lot of the energy behind the ‘change and continuity’ position is in fact to counter some of the worst excesses of this thesis, which for simplicity, we’ll just refer to as ‘The Dung Ages‘ argument, but also because assessing how bad the fall of the Roman Empire in the West was demands that we consider how long-lasting any negative ramifications were.

And with that out of the way, let’s lay some foundation work for what we’re talking about. We’ve had one preamble, yes…but what about second preamble?

A Short History of the (Long) Fifth Century

The chaotic nature of the fragmentation of the Western Roman Empire makes a short recounting of its history difficult but a sense of chronology and how this all played out is going to be necessary so I will try to just hit the highlights.

First, its important to understand that the Roman Empire of the fourth and fifth centuries was not the Roman Empire of the first and second centuries (all AD, to be clear). From 235 to 284, Rome had suffered a seemingly endless series of civil wars, waged against the backdrop of worsening security situations on the Rhine/Danube frontier and a peer conflict in the east against the Sassanid Empire. These wars clearly caused trade and economic disruptions as well as security problems and so the Roman Empire that emerges from the crisis under the rule of Diocletian (r. 284-305), while still powerful and rich by ancient standards, was not as powerful or as rich as in the first two centuries and also had substantially more difficult security problems. And the Romans subsequently are never quite able to shake the habit of regular civil wars.

One of Diocletian’s solutions to this problem was to attempt to split the job of running the empire between multiple emperors; Diocletian wanted a four emperor system (the ‘tetrarchy’ or ‘rule of four’) but what stuck among his successors, particular Constantine (r. 306-337) and his family (who ruled till 363), was an east-west administrative divide, with one emperor in the east and one in the west, both in theory cooperating with each other ruling a single coherent empire. While this was supposed to be a purely administrative divide, in practice, as time went on, the two halves increasing had to make due with their own revenues, armies and administration; this proved catastrophic for the western half, which had less of all of these things (if you are wondering why the East didn’t ride to the rescue, the answer is that great power conflict with the Sassanids). In any event, with the death of Theodosius I in 395, the division of the empire became permanent; never again would one man rule both halves.

We’re going to focus here almost entirely on the western half of the empire; we’ll come back to the eastern half next week.

The situation on the Rhine/Danube frontier was complex. The peoples on the other side of the frontier were not strangers to Roman power; indeed they had been trading, interacting and occasionally raiding and fighting over the borders for some time. That was actually part of the Roman security problem: familiarity had begun to erode the Roman qualitative advantage which had allowed smaller professional Roman armies to consistently win fights on the frontier. The Germanic peoples on the other side had begun to adopt large political organizations (kingdoms, not tribes) and gained familiarity with Roman tactics and weapons. At the same time, population movements (particularly by the Huns) further east in Europe and on the Eurasian Steppe began creating pressure to push these ‘barbarians’ into the empire. This was not necessarily a bad thing: the Romans, after conflict and plague in the late second and third centuries, needed troops and they needed farmers and these ‘barbarians’ could supply both. But as we’ve discussed elsewhere, the Romans make a catastrophic mistake here: instead of reviving the Roman tradition of incorporation, they insisted on effectively permanent apartness for the new arrivals, even when they came – as most would – with initial Roman approval.

This problem blows up in 378 in an event – the Battle of Adrianople – which marks the beginning of the ‘decline and fall’ and thus the start of our ‘long fifth century.’ The Goths, a Germanic-language speaking people, pressured by the Huns had sought entry into Roman territory; the emperor in the East, Valens, agreed because he needed soldiers and farmers and the Goths might well be both. Local officials, however, mistreated the arriving Goth refugees leading to clashes and then a revolt; precisely because the Goths hadn’t been incorporated into the Roman military or civil system (they were settled with their own kings as ‘allies’ – foederati – within Roman territory), when they revolted, they revolted as a united people under arms. The army sent to fight them, under Valens, engaged foolishly before reinforcements could arrive from the West and was defeated.

In the aftermath of the defeat, the Goths moved to settle in the Balkans and it would subsequently prove impossible for the Romans to move them out. Part of the reason for that was that the Romans themselves were hardly unified. I don’t want to get too deep in the weeds here except to note that usurpers and assassinations among the Roman elite are common in this period, which generally prevented any kind of unified Roman response. In particular, it leads Roman leaders (both generals and emperors) desperate for troops, often to fight civil wars against each other, to rely heavily on Gothic (and later other ‘barbarian’) war leaders. Those leaders, often the kings of their own peoples, were not generally looking to burn the empire down, but were looking to create a place for themselves in it and so understandably tended to militate for their own independence and recognition.

Indeed, it was in the context of these sorts of internal squabbles that Rome is first sacked, in 410 by the Visigothic leader Alaric. Alaric was not some wild-eyed barbarian freshly piled over the frontier, but a Roman commander who had joined the Roman army in 392 and probably rose to become king of the Visigoths as well in 395. Alaric had spent much of the decade before 410 alternately feuding with and working under Stilicho, a Romanized Vandal, who had been a key officer under the emperor Theodosius I (r. 379-395) and a major power-player after his death because he controlled Honorius, the young emperor in the West. Honorius’ decision to arrest and execute Stilicho in 408 seems to have precipitated Alaric’s move against Rome. Alaric’s aim was not to destroy Rome, but to get control of Honorius, in particular to get supplies and recognition from him.

That pattern: Roman emperors, generals and foederati kings – all notionally members of the Roman Empire – feuding, was the pattern that would steadily disassemble the Roman Empire in the West. Successful efforts to reassert the direct control of the emperors on foederati territory naturally created resentment among the foederati leaders but also dangerous rivalries in the imperial court; thus Flavius Aetius, a Roman general, after stopping Atilla and assembling a coalition of Visigoths, Franks, Saxons and Burgundians, was assassinated by his own emperor, Valentinian III in 454, who was in turn promptly assassinated by Aetius’ supporters, leading to another crippling succession dispute in which the foederati leaders emerged as crucial power-brokers. Majorian (r. 457-461) looked during his reign like he might be able to reverse this fragmentation, but his efforts at reform offended the senatorial aristocracy in Rome, who then supported the foederati leader Ricimer (half-Seubic, half-Visigoth but also quite Romanized) in killing Majorian and putting the weak Libius Severus (r. 461-465) on the throne. The final act of all of this comes in 476 when another of these ‘barbarian’ leaders, Odoacer, deposed the latest and weakest Roman emperor, the boy Romulus Augustus (generally called Romulus Augustulus – the ‘little’ Augustus) and what was left of the Roman Empire in the west ceased to exist in practice (Odoacer offered to submit to the authority of the Roman Emperor in the East, though one doubts his real sincerity). Augustulus seems to have taken it fairly well – he retired to an estate in Campania originally built by the late Republican Roman general Lucius Licinius Lucullus and lived out his life there in leisure.

The point I want to draw out in all of this is that it is not the case that the Roman Empire in the west was swept over by some destructive military tide. Instead the process here is one in which the parts of the western Roman Empire steadily fragment apart as central control weakens: the empire isn’t destroy from outside, but comes apart from within. While many of the key actors in that are the ‘barbarian’ foederati generals and kings, many are Romans and indeed (as we’ll see next time) there were Romans on both sides of those fissures. Guy Halsall, in Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West (2007) makes this point, that the western Empire is taken apart by actors within the empire, who are largely committed to the empire, acting to enhance their own position within a system the end of which they could not imagine.5

It is perhaps too much to suggest the Roman Empire merely drifted apart peacefully – there was quite a bit of violence here and actors in the old Roman ‘center’ clearly recognized that something was coming apart and made violent efforts to put it back together (as Halsall notes, “The West did not drift hopelessly towards its inevitable fate. It went down kicking, gouging and screaming”) – but it tore apart from the inside rather than being violently overrun from the outside by wholly alien forces.

Living Together

This vision of the collapse of Roman political authority in the West may seem a bit strange to readers who grew up on the popular narrative which still imagines the ‘Fall of Rome’ as a great tide of ‘barbarians’ sweeping over the empire destroying everything in their wake. It’s a vision that remains dominant in popular culture (indulged, for instance, in games like Total War: Attila; we’ve already talked about how strategy games in particular tend to embrace this a-historical annihilation-and-replacement model of conquest). But actually culture is one of the areas where the ‘change and continuity’ crowd have their strongest arguments: finding evidence for continuity in late Roman culture into the early Middle Ages is almost trivially easy. The collapse of Roman authority did not mark a clean cultural break from the past, but rather another stage in a process of cultural fusion and assimilation which had been in process for some time.

This bust, from the Late Roman Republic was typical of a style known as ‘verism’ which aimed to represent the features of an individual very true-to-life, including marks of age and defects.

My apologies in advance to the art historians out there – I am going to do my best to discuss the development of artwork from the Romans into the Middle Ages here, with the relatively meagre technical vocabulary and pool of references I know.

The first thing to remember, as we’ve already discussed, is that the population of the Roman Empire itself was hardly uniform. Rather the Roman empire as it violently expanded, had absorbed numerous peoples – Celtiberians, Iberians, Greeks, Gauls, Syrians, Egyptians, and on and on. Centuries of subsequent Roman rule had led to a process of cultural fusion, whereby those people began to think of themselves as Romani – Romans – as they both adopted previously Roman cultural elements and their Roman counterparts adopted provincial culture elements (like trousers!).6

In particular, by the fifth century, the majority of these self-described Romani, including the overwhelming majority of elites, had already adopted a provincial religion: Christianity, which had in turn become the Roman religion and a core marker of Roman identity by the fifth century. Indeed, the word paganus, increasingly used in this period to refer to the remaining non-Christian population, had a root-meaning of something like ‘country bumpkin,’ reflecting the degree to which for Roman elites and indeed many non-elites, the last fading vestiges of the old Greek and Roman religions were seen as out of touch. Of course Christianity itself came from the fringes of the Empire – a strange mystery cult from the troubled frontier province of Judaea in the Levant which had slowly grown until it had become the dominant religion of the empire, receiving official imperial favor and preference.

The arrival of the ‘barbarians’ didn’t wipe away that fusion culture. With the exception of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes who eventually ended up in England, the new-comers almost uniformly learned the language of the Roman west – Latin – such that their descendants living in those lands, in a sense still speak it, in its modern forms: Spanish, French, Italian, Portuguese, etc. alongside more than a dozen local regional dialects. All are derived from Latin (and not, one might note, from the Germanic languages that the Goths, Vandals, Franks and so on would have been speaking when they crossed the Roman frontier).

They also adopted the Roman religion, Christianity. I suspect sometimes the popular imagination – especially the one that comes with those extraordinarily dumb ‘Christian dark age’ graphs – is that when the ‘barbarians invade’ the Romans were still chilling in their Greco-Roman7 temples, which the ‘barbarians’ burned down. But quite to the contrary – the Romans were the ones shutting down the old pagan temples at the behest of the now Christian Roman emperors, who busied themselves building beautiful and marvelous churches (a point The Bright Ages makes very well in its first chapter).

The ‘barbarians’ didn’t tear down those churches – they built more of them. There was some conflict here – many of the Germanic peoples who moved into the Roman Empire had been converted to Christianity before they did so (again, the Angles and Saxons are the exception here, converting after arrival), but many of them had been converted through a bishop, Ulfilias, from Constantinople who held to a branch of Christian belief called ‘Arianism’ which was regarded as heretical by the Roman authorities. The ‘barbarians’ were thus, at least initially, the wrong sort of Christian and this did cause friction in the fifth century, but by the end of the sixth century nearly all of these new kingdoms created in the wake of the collapse of Roman authority were not only Christian, but had converted to the officially accepted Roman ‘Chalcedonian’ Christianity. We’ll come back later to the idea of the Church as an institution, but for now as a cultural marker, it was adopted by the ‘barbarians’ with aplomb.

Artwork also sees the clear impact of cultural fusion. Often this transition is, I think, misunderstood by students whose knowledge of artwork essentially ‘skips’ Late Antiquity, instead jumping directly from the veristic8 Roman artwork of the late republic and the idealizing artwork of the early empire directly to the heavily stylized artwork of Carolingian period and leads some to conclude that the fall of Rome made the artists ‘bad.’ There are two problems: the decline here isn’t in quality and moreover the change didn’t happen with the fall of the Roman Empire but quite a bit earlier. Hopefully you have been following along with the pictures in this section because they carry a fair bit of my argument here.

Late Roman artwork shows a clear shift into stylization, the representation of objects in a simplified, conventional way. You are likely familiar with many modern, highly developed stylized art forms; the example I use with my students is anime. Anime makes no effort at direct realism – the lines and shading of characters are intentionally simplified, but also bodies are intentionally drawn at the wrong proportions, with oversized faces and eyes and sometimes exaggerated facial expressions. That doesn’t mean it is bad art – all of that stylization is purposeful and requires considerable skill – the large faces, simple lines and big expressions allow animated characters to convey more emotion (at a minimum of animation budget).

Late Roman artwork moves the same way, shifting from efforts to portray individuals as real-to-life as possible (to the point where one can recognize early emperors by their facial features in sculpture, a task I had to be able to perform in some of my art-and-archaeology graduate courses) to efforts to portray an idealized version of a figure. No longer a specific emperor – though some identifying features might remain – but the idea of an emperor. Imperial bearing rendered into a person. That trend towards stylization continues into religious art in the early Middle Ages for the same reason: the figures – Jesus, Mary, saints, and so on – represent ideas as much as they do actual people and so they are drawn in a stylized way to serve as the pure expressions of their idealized nature. Not a person, but holiness, sainthood, charity, and so on.

And it really only takes a casual glance at the artwork I’ve been sprinkling through this section to see how early medieval artwork, even out through the Carolingians (c. 800 AD) owes a lot to late Roman artwork, but also builds on that artwork, particularly by bringing in artistic themes that seem to come from the new arrivals – the decorative twisting patterns and scroll-work which often display the considerable technical skill of an artist (seriously, try drawing some of that free-hand and you suddenly realize that graceful flowing lines in clear symmetrical patterns are actually really hard to render well).

All of the cultural fusion was effectively unavoidable. While we can’t know their population with any certainty, the ‘barbarians’ migrating into the faltering western Empire who would eventually make up the ruling class of the new kingdoms emerging from its collapse seem fairly clearly to have been minorities in the lands they settled into (with the notable exception, again, of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes – as we’re going to see this pattern again and again, Britain has an unusual and rather more traumatic path through this period than much of the rest of Roman Europe). They were, to a significant degree, as Guy Halsall (op. cit.) notes, melting into a sea of Gallo-Romans, or Italo-Romans, or Ibero-Romans.

Even Bryan Ward-Perkins, one of the most vociferous members of the decline-and-fall camp, in his explosively titled The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization (2005) – this is a book whose arguments we will come back to in some detail – is forced to concede that “even in Britain the incomers[sic] had not dispossessed everyone” of their land, but rather “the invaders entered the empire in groups that were small enough to leave plenty to share with the locals” (66-7). No vast replacement wave this, instead the new and old ended up side by side. Indeed, Odoacer, seizing control of Italy in 476, we are told, redistributed a third of the land; it’s unclear if this meant the land itself or the tax revenue on it, but in either case clearly the majority of the land remained in the hands of the locals which, by this point in the development of the Roman countryside, will have mostly meant in the hands of the local aristocracy.9

Instead, as Ralph Mathisen documents in Roman aristocrats in barbarian Gaul: strategies for survival in an age of transition (1993), most of the old Roman aristocracy seems to have adapted to their changing rulers. As we’ll discuss next week, the vibrant local government of the early Roman empire had already substantially atrophied before the ‘barbarians’ had even arrived, so for local notables who were rich but nevertheless lived below the sort of mega-wealth that could make one a player on the imperial stage, little real voice in government was lost when they traded a distant, unaccountable imperial government for a close-by, unaccountable ‘barbarian’ one. Instead, as Mathisen notes, some of the Gallo-Roman elite retreat into their books and estates, while more are co-opted into the administration of these new breakaway kingdoms, who after all need literate administrators beyond what the ‘barbarians’ can provide. Mathisen notes that in other cases, Gallo-Roman aristocrats with ambitions simply transferred those ambitions from the older imperial hierarchy to the newer ecclesiastical one; we’ll talk more about the church as an institution next week. Distinct in the fifth century, by the end of the sixth century in Gaul, the two aristocracies: the barbarian warrior-aristocracy and the Gallo-Roman civic aristocracy had melded into one, intermarried and sharing the same religion, values and culture.

In this sense there really is a very strong argument to be made that the ‘Romans’ and indeed Roman culture never left Rome’s lost western provinces – the collapse of the political order did not bring with it the collapse of the Roman linguistic or cultural sphere, even if it did fragment it.

But surely the barbarians burned all of the libraries, right? Or the church, bent on creating a ‘Christian dark age’ tore up all of the books?

Literature

Well, no.

Here I think the problem is the baseline we assess this period against. Most people are generally aware that the Greeks and Romans wrote a lot of things and that we have relatively few of them. Even if we confine ourselves only to very successful, famous Greek and Roman literature, we still only have perhaps a low single-digit percentage of it, possibly only a fraction of a percent of it. In our post-printing-press and now post-internet world, famous works of literature do not simply vanish, generally and it is intuitive to assume that all of these lost works must have been the result of some catastrophe or intentional sabotage.

I am regularly, for instance, asked how I feel about the burning of the Library of Alexandria. The answer is…not very much. The library burned more than once and by the time it did it was no longer the epicenter of learning in the Mediterranean world. Instead, the library slowly declined as it became less unique because other libraries amassed considerable collections. There was no great, tragic moment where countless works were all lost in an instant. That’s not how the chain of transmission breaks. Because a break in the chain of transmission requires no catastrophe – it merely requires neglect.

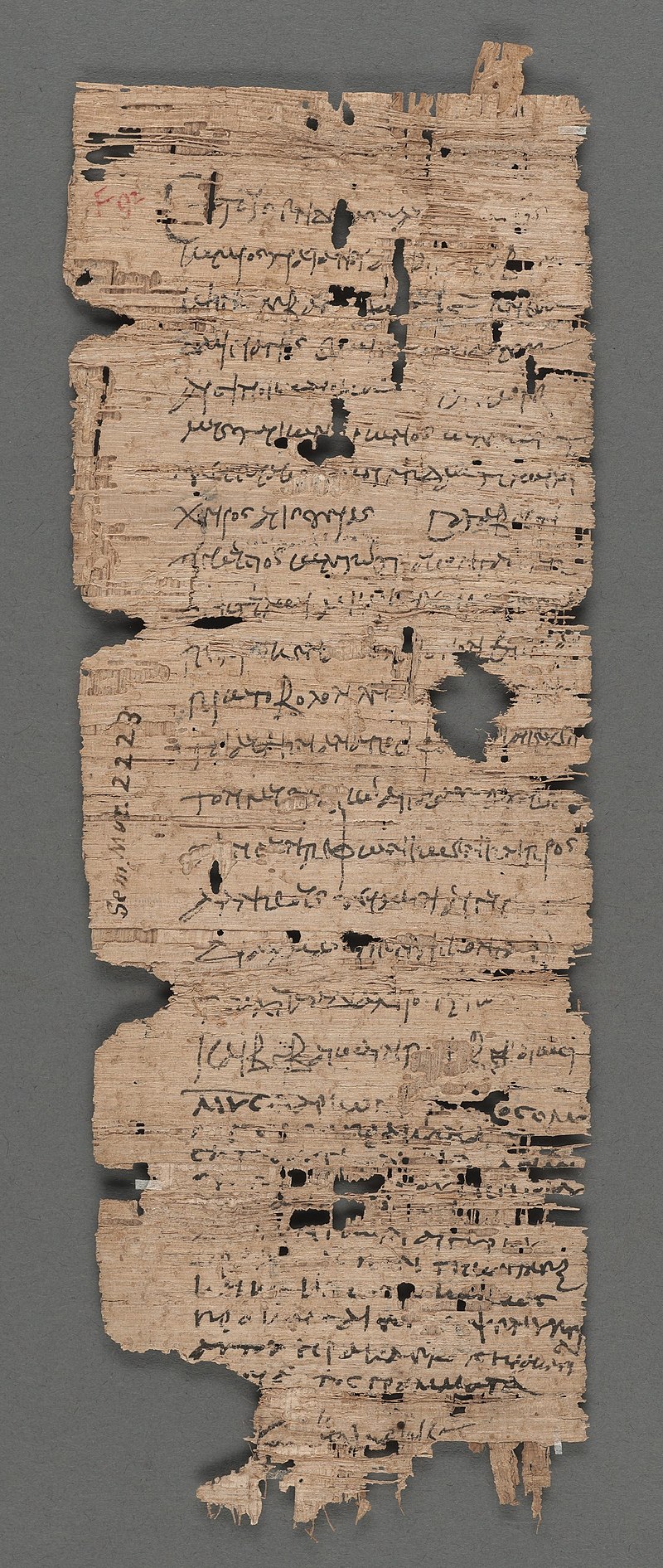

The literature of the Greeks and Romans (and the rest of the ancient iron age Mediterranean) were largely written on papyrus paper, arranged into scrolls.10 The problem here is that papyrus is quite vulnerable to moisture and decay; in the prevailing conditions in much of Europe papyrus might only last a few decades. Ancient papyri really only survive to the present in areas of hard desert (like Egypt, conveniently), but even in antiquity, books written on papyrus would have been constantly wearing out and needing to be replaced.

Consequently, it didn’t require anyone going out and destroying books to cause a break in the chain of transmission: all that needed to happen was for the copying to stop, even fairly briefly. Fortunately for everyone, Late Antiquity was bringing with it a new writing material, parchment, and a new way of putting it together, the codex or book. The transition from papyrus to parchment begins in the fourth century, but some books are still being produced in papyrus in the 7th century, particularly in the Eastern Mediterranean. Whereas papyrus is a paper made of papyrus stalks pressed together, parchment is essentially a form of leather, cleaned, soaked in calcium lye and scraped very thin. The good news is that as a result, parchment lasts – I have read without difficulty from 1200 year old books written on parchment (via microfilm) and paged through 600 year old books with my own hands. Because making it requires animal hide, parchment was extremely expensive (and still is) but its durability is a huge boon to us because it means that works that got copied onto parchment during the early middle ages often survive on that parchment down to the present.

But of course that means that the moment of technological transition from short-lived papyrus to long-lasting parchment was always going to be the moment of loss in transition: works that made it to parchment would largely survive to the present, while works that were not copied in that fairly narrow window (occupying Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages) would be permanently lost. And that copying was no simple thing: it was expensive and slow. The materials were expensive, but producing a book also required highly trained scribes (often these were monks) who would hand copy, letter by letter, the text for hundreds of pages. And, for reasons we’ll talk about later in this series, the resources available for this kind of copying would hit an all-time-low during the period from the fifth to the seventh centuries – this was expensive work for poor societies to engage in.

And here it is worth thus stopping to note how exceptional a moment of preservation this period is. The literary tradition of Mediterranean antiquity represents the oldest literary tradition to survive in an unbroken line of transmission to the present (alongside Chinese literature).11 The literary traditions of the Bronze Age (c. 3000-1200 BC and the period directly before antiquity broadly construed) were all lost and had to be rediscovered, with stone and clay tablets recovered archaeologically and written languages reconstructed. The Greeks and Romans certainly made little effort to preserve the literature of those who went before them!12

In that context, what is actually historically remarkable here is not that the people of Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages lost some books – books had always been being lost, since writing began – but that they saved some books.13 Never before had a literary tradition been saved in this way. Of course these early copyists didn’t always copy what we might like. Unsurprisingly, Christian monks copying books tended to copy a lot more religious texts (both scriptures but also patristic texts). Moreover, works that were seen as important for teaching good Latin (Cicero, Vergil, etc.) tended to get copied more as well, though this is nothing new; the role of the Iliad and the Odyssey in teaching Greek is probably why their manuscript traditions are so incredibly robust. In any event, far from destroying the literature of classical antiquity, it was the medieval Church itself that was the single institution most engaged in the preservation of it.

At the same time, writers in the fifth, sixth and seventh centuries did not stop writing (or stop reading). Much of the literature of this period was religious in nature, but that is no reason to dismiss it (far more of the literature of the Classical world was religious in nature than you likely think, by the by). St. Augustine of Hippo was writing during the fifth century; indeed his The City of God, one of the foundational works of Christian literature, was written in response to the news of the sack of Rome in 410. Isidore of Seville (560-636) was famous for his Etymologies, an encyclopedia of sorts which would form the foundation for much of medieval learning and which in its summaries preserves for us quite a lot of classical bits and bobs which would have otherwise been lost; he also invented the period, comma and colon. Pope Gregory I (540-604) was also a prolific writer, writing hundreds of letters, a collection of four books of dialogues, a life of St. Benedict, a book on the role of bishops, a commentary on the Book of Job and so on. The Rule of St. Benedict, since we’ve brought the fellow up, written in 516 established the foundation for western monasticism.

And while we’ve mostly left the East off for this post, we should also note that writing hardly stopped there. Near to my heart, the emperor Maurice (r. 582-602) wrote the Strategikon, an important and quite informative manual of war which presents, among other things, a fairly sophisticated vision of combined arms warfare. Roman law also survived in tremendous quantities; the emperor Theodosius II (r. 402-450) commissioned the creation of a streamlined law code compiling all of the disparate Roman laws into the Codex Theodosianus, issued in 439. Interestingly, Alaric II (r. 457-507), king of the Visigoths in much of post-Roman Spain would reissue the code as past of the law for his own kingdom in 506 as part of the Breviary of Alaric. Meanwhile, back at Constantinople, Justinian I (r. 527-565) commissioned an even more massive collection of laws, the Corpus Iuris Civilis, issued from 529 to 534 in four parts; a colossal achievement in legal scholarship, it is almost impossible to overstate how important the Corpus Iuris Civilis is for our knowledge of Roman law.

And it is not hard again to see how these sorts of literary projects represented a continuing legacy of Roman culture too (particularly the Roman culture of the third and fourth century), concerned with Roman law, Roman learning and the Roman religion, Christianity. And so when it comes to culture and literature, it seems that the change-and-continuity knight holds the field – there is quite a lot of evidence for the survival of elements of Roman culture in post-Roman western Europe, from language, to religion, to artwork and literature. Now we haven’t talked about social and economic structures (that’s part III), so one might argue we haven’t quite covered all of ‘culture’ just yet, and it is necessary to note that this continuity was sometimes uneven. Nevertheless, the fall of Rome can hardly be said to have been the end of Roman culture.

Next time, we’ll turn to the institutions of the Roman world: cities, government, administration, and the Church and see how they fared.

- The sort of footnote where you show that you have read and understood the history of the debate you are about to comment on. When this sort of footnote ascends to being part of the actual text of a work, it is called a ‘literature review.’

- I am going to refer here to ‘ancient historians’ and ‘medievalists’ here because I think there is a noticeable difference in how the two fields on either side of this period tend to think about it. Of course these labels can be reductive to a degree so please understand them as necessary simplifications of the shape of the field

- I do not mean here to trash The Bright Ages, which I think on the whole is very good and probably due for a fireside recommendation. That said, I did find myself somewhat frustrated by the first few chapters which embrace the ‘change and continuity’ school as if there was no serious challenge to it – as we’ll see, an absolutist position I do not think can survive the evidence. I was much more frustrated by the deflection to insist that the only way one can imagine there was a ‘fall’ was to be the sort of person convinced that “Germans couldn’t really be Romans, women couldn’t really be rulers, etc.” (13) It is an ad hominem deflection unworthy of the rest of the book. Anyone even passingly acquainted with my writings here on this blog will know that I absolutely think Germans could be Romans and women were rulers. The implication of the deflection does a disservice to the lay reader who may thus be mislead as to the existence of real counter-arguments.

- that is, ‘change and continuity’

- That position isn’t unchallenged, mind you. P. Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History (2006) makes the opposing argument that the Germanic peoples were a coherent ethnic grouping that displaced the pre-existing Roman culture. Here I think Halsall has the better of the argument, both in the sense that the various Germanic peoples were hardly a single group but also that they seem more to have fused with the Roman cultural fabric than replaced it, as we’ll see.

- Often for the sake of clarity, we’ll refer to the Latin-speaking provincials of this period as Gallo-Romans, Ibero-Romans or Romano-Britons or the like. Nevertheless in our sources these fellows tend to be quite clear that they think of themselves as Romans, whatever other local habits they may have.

- The Romanist in me feels the need to note that I am using this term because I have no doubt it is the one I’d hear in this context, but Greek and Roman temples are, in fact, structurally different, just as Greek and Roman religion was, in fact, meaningfully distinct

- Real to life.

- Now we’ll come back to the economic implications of this later, for now we are merely noting that the existing population was not pushed aside or wiped out

- By the by, I think we’ll come back sometime this year and do a series on ‘How Did They Make It: Books’ but in the meantime, there is a solid introduction in the first section of B. Bischoff, Latin Paleography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages, trans. D. O. Cróinin and D. Ganz (1990)

- Please note before anyone rushes to the comment that I have drawn this particular definition – the literary tradition of Mediterranean antiquity – broad enough to also encompass the Torah.

- Though I will say that the Greeks in particular did make more of an effort than most ancient civilizations to write about the myths and cultures that surrounded them. The sort of ethnographic curiosity of Herodotus or Plutarch is quite hard to find in most places.

- Of course we are mostly focused here on the Latin tradition which tended to survive in the West, though the same here might well be said for the Greek tradition, mostly preserved in the East, in the remains of the Eastern Roman Empire and also in the Islamic world.

Great start to what I am sure will be a great series! I do have several questions though.

1)You mention the Crisis of the Third Century and the mass of civil wars that both were a cause and a symptom of the political fragmentation of the WRE that would persist until it no longer existed as a political entity. I’ll admit my knowledge of the Early Imperial period is fairly sparse, but why weren’t you having civil wars left right and center during the 1st and 2nd centuries? After all, they were sandwiched by periods of endemic civil war on both sides.

2) Why did the shift to parchment happen in a large scale around Late Antiquity? I know for a fact that most of the Dead Sea Scrolls were made of parchment (although some were Papyrus, and interestingly, there are a couple of “scrolls” made on engraved copper) and considerably older than Late Antiquity. So there must have been at least a few people making parchment prior to that.

3) I never played Atilla: Total war. But I did play the earlier RTW: Barbarian invasions. And in that older game, as the WRE, it was definitely the case that your own internal issues tended to be way bigger than huge hordes of barbarians swarming across the Danube. (In fact, one of the keys to surviving as the WRE is to try to maneuver the rebels and the external invaders into fighting each other whenever possible). And the introduction of the “Loyalty” mechanic caused you endless headaches. I had more than one army sent out to subdue those invaders turn against me, often supplementing the forces I sent them out with with the very barbarians they were supposed to be stomping on. Not that I’m claiming BI is some model of historical accuracy, but it certainly seemed more nuanced than what you’re presenting with the later game. And these are made by the same company and only about 10 years apart. What do you think caused the shift in presentation?

I’m only going to touch on the first point because the other ones are out of my wheelhouse, but there were several civil wars in the 1st and 2nd century (mostly the 1st, though the closing of the 2nd century was quite violent).

These civil wars though were not as long lasting as the ones that would happen later, and they happened against a backdrop of good times for the empire – the plagues, fiscal mismanagement and external pressures that would characterize the 3rd century had not manifested yet.

re the papyrus-parchment transition: It was a gradual and lengthy process. Parchment was probably invented sometime in the 1st millennium BCE, somewhere in the middle east. It took a long time to become ubiquitous. In the Roman world it actually first gets mentioned in the late Republic as an alternative to wax covered wooden tablets for making notes.

As far as books went, papyrus was traditional, and parchment was a new thing, seen as less desirable. It was cheaper than parchment and supplies were less constrained – it’s easier to plant more fields with papyrus plants than it is to raise more cows/sheep. But most of all, the papyrus export buisness was a HUGE industry in Egypt with a lot of capital behind it, and those papyrus makers and exporters worked hard to maintain their monopoly and keep parchment manufacturers from gaining a foothold. Parchment gradually gained popularity due to its durability, but it became the primary writing material only where transport costs made papyrus more expensive. The dissolution of the empire in the West threw up trade barriers, obviously. In the East, and in Arabia, papyrus continued to be used alongside parchment, and Egypt continued to manufacture and export it right down until the arrival of paper in the Islamic world at the end of the first millennium CE.

Reference: “The Birth of the Codex” by Colin Roberts and T C Skeat. I wrote about this on my blog at length a few months ago.

Very interesting. Thanks for the heads up.

“hose papyrus makers and exporters worked hard to maintain their monopoly and keep parchment manufacturers from gaining a foothold”

How did they do that?

I imagine the main tools were bribes to the right lawmakers to get higher tariffs/taxes on parchment, and using their vast stores of wealth to undercut folks trying to get a parchment business going until their competitor collapsed. Not too different from modern economics.

Papyrus was simply cheaper and more available than parchment – and most writing is ephemeral. After all, the papyri found in Egyptian deposits are mostly bills of sale, school exercises and other mundane notes. A 20 year lifespan is no problem for these. If your average Roman lending library attached to a public bath wanted a collection of stories (eg the many Hellenistic novels featuring separated lovers, pirates and mistaken identity – the classical equivalent of Mills & Boon) then papyrus scrolls were on offer from the scriptorium around the corner. Papyrus was the equivalent of the file note and the paperback; parchment was the hardcover.

I’ve played Barbarian Invasion and Atilla a lot and I think you missinterpret Brett’s point. In both games the Western Roman Empire has obvious and historical internal problems.

If/when a barbarian horde settles in a formerly Roman region, that region becomes a gothic/Aleman/whatever region not just politically but culturally and (implicitly) ethnically. The player (or AI) can only build buildings of it’s own culture and remaining Roman buildings provide a public order malus.

Brett’s argument is that in reality the culture and ethnicity of a conquered region stayed mostly Roman. That is: in reality the invaders were mostly absorbed, whereas in the games the invaders replace the Romans.

In this aspect there is no discontinuity between Rome: Barbarian Invasions and Atilla.

Attila tends to actually give nods to the cultural synthesis thing, both in the actual main campaign (the ostrogoths can continue to make use of “roman” style buildings, the other “migrator” factions can more cheaply conver them, and the western romans can recruit units from friendly “barbarian” tribes)

The major faction they actually do a disservice to are the huns,

I’d also note that the WRE in Attila has the same thing: The barbarians aren’t really the major problem, and any proper army can probably defeat them, the problem is that there are too many fronts to cover, that your economy is dogshit, everyone is unhappy, fixing all of those things requires money, and the climate keeps getting worse which means you have to constantly change your provincial building setups (away from wheat and towards goats, mostly…) to account for that. And all of those things cost money…

Expanding on the first question (and answered by others), part of the stability at the beginning of the imperial period comes from the fact that there simply weren’t any nobles with the standing to make a play for the throne – the preceding civil wars had killed them off.

Then Octavianus/Augustus ensured that ambitious senators would be denied opportunities to gain military glory and potentially the loyalty of the legions by arranging to control the vast majority of the legions and to appoint only his loyalists.

This mostly works until 69CE when a usurper leads some German legions in rebellion, Nero offs himself and the senate in turn appoint Galba as the new emperor who in turn gets offed by Otho who bribed the Praetorians, who in turns offs himself after his army loses a battle against that original usurper, Vitellius, who in turn gets offed when he loses a battle against another general, Vespasianus, who was also taking a run for the purple.

After Flavian dynasty the following emperors generally adopted their replacement allowing them to select experienced proven military men. Once again, these men had the stature, popularity, and skill to keep the legions loyal and the populace content. It kinda fell apart when Marcus Aurelius appointed his actual son who’s a bit of a disaster prompting an assassination and then civil war with 5 emperors in 193.

During this period, it seems one required a senatorial background in addition to access to a loyal army. When we get to the year of the five emperors we start to see men of equestrian origin feeling like they could make a play for the throne. By the later centuries the mystique of noble birth seems to have faded completely and the main requirement became a loyal army, usually acquired through successful military campaigns.

AFAIK

A Roman Empereors legitimacy wasfounded on his protection of the empire, if he or the empire lacked the ressources to do so he lost it,

So if Gaul was invaded and the Balkans and he could only defend one at the moment, he lost his legitinacy

In terms of the cultural continuity in action, Scots law has a strong civilian tradition. To the point that you could probably quote the Corpus Iuris Civilis (or the Institutes of Justin’s as its often referred to) in a Scottish court and not be laughed at. It was a compulsory part of the law syllabus at my university.

One of the signs of the fall of Rome is the depopulation of the cities. How much of that is due to politically forced economic collapse, from a climate change, and/or from natural disasters like the plague of Justinian and the big volcanic eruptions from the first half of fifth century that caused a decade long ice age?

Correction, sixth century (536 and 539-40).

Came here to mention that. Although part 1 focuses mostly on the fifth century, any look at European history in late antiquity/ early medieval times has to acknowledge the natural catastrophes of the sixth century. Similar to the role of the Thera cataclysm in either causing or cementing the late Bronze Age collapse.

No, part I is about culture.

“In part I (this part), I want to focus on culture, literature, language and religion (‘words’)”

“finally in part III, we’ll turn to look at economics and demographics”

Exact dating of the Thera eruption is controversial but all the serious suggestions are around 1600 BC ± 50 years or so. Perhaps a little early to have played a role in the post 1200 late bronze age collapse.

So, I see online graphs (a _bit_ better than the one you rightly dunk on at the beginning of your article, I hope) which show that the population of Rome (the city) did, in fact, decline precipitously at about the time we think of “the fall of Rome”, at least when viewed from the standpoint of centuries. Then, it remains low until about the time of the Renaissance, when it starts to rise again. Most people mean something more than just population when they talk about “the fall of Rome”, but it is at least indicative of the ability of the society to maintain a large urban center. I will be curious to hear how the “continuity and change” knight does in regards to alleged data such as that. Interesting topic!

It bears mentioning that Rome ceased to the capital of its own empire under Constantine (in 325 A.D. IIRC). Under the east/west division, it wasn’t even the capital of the west.

Even before then, Diocletian’s “imperial colleague” Maximian ruled the western provinces from Milan rather than Rome. A pop history writer I read speculated that both of them were country boys who disliked ‘The City’ and its privileges (Diocletian himself never even visited Rome)

I suspect that the real pattern was with the increasing militarisation of rule during the Crisis, where the role of Emperor as commander of the army was prioritised over his role as civic leader – and indeed an Emperor who didn’t have a loyal army at his back was likely to be overthrown by one who did. At the same time, the weakening of the central administration caused by this instabilty led to more pressure on the frontiers, which meant the soldier-Emperors had to spend more time out on campaign and Rome was no longer a suitable base of operations. The model of rule used by Augustus or Antoninus where they were able to rule from Rome and delegate military affairs completely simply didn’t work during a protracted period of barracks emperors and civil wars.

Rome clearly retained some symbolic importance, otherwise Aurelian wouldn’t have invested in its walls (and the new fortifications proved their worth when Maxentius came to defend them), and may still have been the economic capital of the west, but the political capital was most likely “wherever the Emperor currently is”.

Diocletian (and Maximian) may have been provincials who disliked the metropolis on principle but I imagine that the official shift of government to Milan and Nicomedia (and later Constantinople) was really more about formalising the reality of the situation as it existed than it was about making a statement snubbing the old city.

One important point to remember is that the population of a single city is a good proxy for the fortunes of that particular city, but not so much for the fortunes of the entire civilization that city is a part of.

Athens, for example, was probably a lot more prominent and wealthy and quite possibly more populous in 450 BC than in 250 BC, but that doesn’t mean Greek civilization as a whole was in decline or had been declining steadily during that time. New centers of power had become more significant, and a lot of resources that were formerly diverted to swell up one place (think “Delian League”) were instead staying at home or going elsewhere.

Likewise, the massive population of the city of Rome during the late Republic and early/mid-Empire was the result of the Romans systematically taxing and pillaging much of the wealth of the Mediterranean and putting it into the hands of a Rome-centered aristocracy, one which made it a major component of state policy to ensure massive grain imports from as far away as Egypt, all funneling into Rome. Rome’s ability to become a mega-city by ancient standards was inseparable from its status as an imperial capital, and once it lost that status it was inevitably going to shrink back down towards something more in line with the size of other major Mediterranean cities.

All Roman cities declined in size. The qulity of living (sewers, aqueducts, roads) was kept by inertia (initial good engineering) until they were wrekced by the first war / earthquake. Afterwards the cities declined even faster.

I’m sure you’re right- it’s just that Rome in particular had entirely separate reasons to shrink in size much more than most other Roman cities, so it’s an unusually bad example.

IMHO a simple answer is that the city Rome was an artificially large urban center sustained on tribute of the whole empire, transferring wealth (much of it in the form of grain) from provinces to Rome. As soon as the empire gets divided, this wealth and grain starts enriching (and populating!) the local urban centers instead of the city of Rome. Major capitals are not fed solely by manufacturing and trade, they are fed by extraction of agriculture not only from local regions but by the governing elites extracting value of far-away holdings throughout the empire. The city of Constantinople would not be possible without a decline of the city of Rome, it required that the extracted surplus of Greek and Anatolian lands stops going to elites living in Rome and starts going to elites living in Constantinople instead, the same applies for Paris and other regions.

I think this is right– and North African and Sicilian grain is a big part of the picture; once it’s being directed to Constantinople, it’s not going to Rome. Neither is as much Imperial patronage and administrative work.

Great stuff as always, Dr. Devereaux. I think this is an appropriate place to share an interview of Polymnia Athanassiadi by Anthony Kaldellis, more focused on the Roman east than the west. If we insist on categories, let’s say that Kaldellis is in the continuity and change school and Athanassiadi is in the decline and fall school.

https://pca.st/kz259yno

“A conversation with Polymnia Athanassiadi (University of Athens) about the way of life that ended in late antiquity. Scholars of Byzantium and the Middle Ages may see this as a period of new beginnings, but Polymnia doesn’t want us to forget the practices and urban values that came to an end during it. The conversation touches on issues raised throughout her papers collected in Mutations of Hellenism in Late Antiquity (Variorum Ashgate 2015), as well as the concept of “monodoxy” explored in Vers la pensée unique: La montée de l’intolerance dans l’Antiquité tardive (Les Belles Lettres 2010).”

Looking at the end of the Western Roman Empire, that’s a bear of a job. I’m happy to see your version of it, though, and even happier to see you presenting the leading debating theories. My own contribution is merely in pointing out a couple of mispellings.

“while still powerful and rich by ancient standards, was not as powerful or as rich as in the first two centuries and also had substantially more difficulty security problems.”

I believe the writing should be “substantially more difficult security problems.”

“The peoples on the other side of the frontier were not strangers to Roman power; indeed they had been trading, interacting and occasionally raiding and fighting over the boarders for some time.”

Again, I think this should be “borders,” not “boarders.”

Also, “opnely” should be “openly.”

Both fixed!

Would you consider a pre-publication volunteer proofreader?

Matt, more than one volunteer would be better, as they often catch different stuff (editor and proofreader here, as well as someone who does a lot of writing). On the subject of proofreading: I know that I will not contribute to Prof. Devereaux’s Patreon until his writing is properly proofread.

If you’re an editor and proofreader, then you know that we’re probably talking about line editing, rather than proper proofreading.

“(Odoacer offered to submit to the authority of the Roman Emperor in the West, though one doubts his real sincerity)”

Is that supposed to be East? What with the caption mentioning Emperor Zeno below.

Great topic for a series! Concerning the Tetrarchs wearing crowns, it might surprise some Rome-fanboys that Aurelian was the first Emperor to introduce the royal diadem, at least according to the Epitome De Caesaribus

You put that as if that would stop me from loving Aurelian.

If I may add to the dunking on that nitwit’s graph, here’s a question:

If there WAS a big old collapse of science, of cultural complexity and all that jazz, how does that square with the whole colonialism thing emanating from Europe as oppposed to yanno…China?

Like, maybe my problem is I’m coming from this at a weird angle forged from two seperate bits of pop history, and forcing them to defend each other but…

Well that’s obvious. See, the Chinese were far too enlightnened to go out and conquer and exploit faraway peoples, they had everything they needed right there in China. It was only the EVIL Europeans who had regressed into comedic levels of stupidity and greed because they adopted Christianity that felt a need to swarm out all over the world to spread their virus of a religion and steal things from others!

(This is of course a sarcastic take, but I’ve heard elements of it expressed in all seriousness)

The kind of people that buy into the christian dark ages also tend to believe modern western culture is the epitome of all that is good.

They don’t actually ever think about china or india or anything outside europe

The people I’ve seen making dunked-graph-esque takes are usually more eager to downplay non-European accomplishments than their historical atrocities. They’d probably say that Europe got global imperialism before China because China didn’t have any Greco-Roman culture to rediscover. And hey, it just so happens that the Renaissance took place just a bit before Colombus discovered America! There’s probably a causal link there, right?

LOL. Amusing to note that the author is compelled by Poe’s Law to note that he is being sarcastic.

Serious answer: Europe was rather a backwater during the medieval, and only caught up to the various Chinese, Indian, Turkish and Mongolian empires with the conquest of the Americas. The second question is “why did no-one else colonize Europe during that interval” and the answer to that is twofold. They did where they could (see: Al-Andalus, parts of Italy and France) and the land was valuable. However, the technologies that made resource extraction from administratively undeveloped regions logistically viable (namely, rails) did not yet exist.

Europe was on-par or actually ahead of Middle East and Asia from about 1000 AD. The Europeans reconquered Sicily, Anatolia, Cyprus, Spain, forced the integration of Hungary, Poland and Russia into Christian oikumene. They also rolled back the Mongols and kept them confined into Ukraine. Overall they did better compared to Song, Kwarazm or the Mameluks.

And held their own in Palestine for several centuries during the Crusades.

You have a very small definition of ‘several’; the crusader states didn’t even last two full centuries.

The Year 1000 is a bit early – the Mongols were in the 1200s, as was Los Navas de Tolosa. Hungary, Poland and Russia were not “forced” into Christianity. Fairer to say that by 1200 the wealthier parts of Europe (southern Britain, Northern Italy, northern France, the Netherlands, the Rhinelands…) were on a par with the wealthier parts of China, India or the Middle East. It was not until 1700 or later that Europe started to really pull ahead.

It wasn’t so much that Hungary won, so much as Batu lost. See, ya boy Batu never read Bret’s post on how the Mongols weren’t magical teleporting warmasters, and relied on complex logistics networks of their own. So he decided it was a good idea to lunge his troops over the Ural mountains in late summer, with no connection to the rest of the Khanate. Cue winter, impassable snow in the Urals, and everyone running out of food. Batu muttered something about his granddad’s funeral and skedaddled as soon as the snow melted.

This is not meant of a defense of Mr. Nitwit, but it is worth pointing out that Chinese-based states were clearly far wealthier and more powerful than anything in western Europe for pretty much the entire period from the putative fall of Rome until the early modern era. Colonialism’s emergence from Europe is very much not a product of Europe’s relative success in the 7th century (to pick an example when the contrast between Europe and China is quite extreme).

Even if we don’t consider it a straight up fall, it’s not like Europe was wealthier or more advanced than China at that point. The age of exploration and scientific revolution were what really precipitated a massive snowballing technological advantage that eventually resulted in that crushing military superiority. It’s possible to argue that the seeds of this were already being planted, but that doesn’t require that there wasn’t a collapse – sometimes societies fall fast and recover even faster. Look how long it took Japan to go from closed medieval country to modern industrial imperial power.

I think there is an argument that the age of exploration itself didn’t change that much: Europeans were in some ways militarily more successful, but not neccessarily *wealthier* until the Industrial Revolution Changed Everything.

The Edo era was not really “medieval” in any meaningful sense. Edo was already a huge city, and Japan was very wealthy and literate for a non-industrialized nation. They also had been sort of keeping tabs on European advancements (rangaku) though unevenly. Iron ships were new (in the sense Japan could not make them) but guns were not. Japan was well prepared to make the leap, because they had an educated elite and knew they were up against more powerful countries. The samurai elite that sided with the “imperial restoration” faction became the new leaders, and they were backed up by an educated middle class (haiku and ukiyo-e were middle class arts).

There was a lot of luck too, but it’s a lot like what China has done in the last 30 years. They knew what they didn’t know and so attacked those points aggressively. An example is what China squeezed from Apple – the articles that go into it make it clear Chinese authorities demanded technology transfers and explicitly setting up R&D in China in return for Apple’s involvement in China. The leadership in Japan, heck, the entire country down to country bumpkins moving into the cities, adopted western things aggressively.

My understanding is that China had far greater scope for practicing colonialism in their own backyard – my language skills are very bad, but for example I understand the “Nam” of “Vietnam” to mean “southern” – the same word as begins “Nanjing”, yet the land north of Vietnam is now considered to be Chinese. Whatever culture had been there before has been Sinicized.

Dr Devereaux contended at one point (EU4 part 4: Why Europe?) that whatever Afroeurasian society was the first to resolve the logistical barriers to putting an army in the New World was also very likely to conquer it. Europe was consistently at the cutting edge of seafaring technologies by necessity, thanks to the comparative fragmentation of the land relative to the great Indian and Chinese basins. (The Polynesians were notably even more successful, but had not the numbers.)

Why would the Europeans make the trip? The answer I usually hear is about religiously-motivated closure of the overland trade route to the east, with the fall of Constantinople, but I’m not sure I buy that that one obstacle represents such a stark increase in the danger.

There’s a clearer survey of the answers to “Why Europe?” on this blog at:

https://acoup.blog/2021/05/28/collections-teaching-paradox-europa-universalis-iv-part-iv-why-europe/

I have no formal training in these matters, though, and would welcome being set right by one who knows better.

> Why would the Europeans make the trip? The answer I usually hear is about religiously-motivated closure of the overland trade route to the east, with the fall of Constantinople, but I’m not sure I buy that that one obstacle represents such a stark increase in the danger.

The answer I usually hear is that sea travel is faster and cheaper than land travel, especially if the land route is divided between multiple states (as it was after the fall of the Mongol Empire).

I suspect there’s some truth to the “land route closing” factor, but it’s not just a matter of Constantinople falling, it’s the more general phenomenon.

1) The Central Asian component of the land route fell into disarray as the Mongols fragmented and new factions sprung up.

2) The Ottomans were a rising power that, by the late 1400s, sat across [i]most[/i] of the land routes from Europe to Asia, if not all of them.

3) While the Mamelukes in Egypt theoretically let you do an end-run around the Ottomans up until the 1510s in some ways… The people who did most of the trading with the Mamelukes were the Venetians, as I recall. Importantly, Spain and Portugal weren’t friends in this situation. To Spain, Venice was competition against Spain’s own influence.

AIUI Indian Ocean trade was much much more important than the land routes, as would make sense, but the Ottomans closing off access to that probably still works. Especially from the POV of Spain and Portugal.

If nothing else, the budding conflict in the Eastern Mediterranean between the Venetians (et al.) and the Ottomans could have been disrupting trade patterns somewhat even before the Ottomans directly seized the key port locations in Egypt in the 1510s.

The Ottomans did not close the trade routes – they (and Safavid Persia) fought the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean to prevent the Portuguese from closing the routes. They failed, and the Portuguese and subsequently Dutch and then British were able to forcibly redirect trade from the Red Sea and Persian Gulf to the Cape.

Nan means south, but like, Nanjing was only “colonized” in the same sense that Greece was colonized by Rome

The line between conquest and colonization is awfully hazy…seems to be about how many of “your” people end up living there.

Eh…. Not exactly. It’s a bit of a weird comparison because Nanjing postdates the colonization/migration period, which started at some point during the Han (though even then large parts of southern China was only in a very vague sense under chinese control) and accelerated during the instability of the following periods.

It gets complicated because the demographics are often… patchy (still are, to some extents) with pre-han populations (like the ancestors of the Vietnamese before they were pushed south) often being pushed into the mountains. (the same is true, to an even greater extent, for the Yunnan area,.

Europeans explored and ultimately colonized because there wasn’t much worth having in Europe.

By say 1450, south-east England, the Netherlands and north Italy were comparable to coastal China in wealth, sophistication and technology. The decisive break came with the discovery of the Americas – but one you can reach the Cape of Good Hope the Americas become inevitable (the winds take you out near to Brazil).

I think this statement could be much more sensibly stated as ‘everything “worth having” in Western Europe was becoming locked down by peer states’

Given Columbuses known objective of navigating clear around the world to the East though, the trade theory provides a fairly clear impetus for the crowded-out western seafaring states to start seriously considering funding people like Jim’s harebrained expeditions around the world.

“there wasn’t much worth having in europe”

Wool, clockwork, wood (a massive constrain for the caliphates), high quality steel (sold down to africa) and banking invented by of all groups the knights templar.

The real point is that Europe wanted things from the Far East: spices, silk, porcelain. Europe did not have much that the Far East wanted, certainly worth the hassle. Even in the 1500s, Europe’s main “export” was either silver stolen from the Americas, or outright piracy by the Portuguese.

What’s a good sarcastic euphemism for piracy? Exporting lead? Were naval cannons commonly used by 16th-century pirates?

Obviously, if it does not emanate from Europe, it isn’t colonialism or imperialism.

The Turks last attempt to conquer Central Europe, for example, was in 1683, more than thousand years after the Fall of Rome, and almost two centuries after Christopher Columbus sailed, but that doesn’t count as imperialism or colonialism because they weren’t coming from Europe. Quite the reverse, in fact.

I think that an honest review of the literature in Europe regarding the Ottoman Empire, over the past several hundred years and including the present day, would suggest otherwise.

There is no shortage of people prepared to speak at considerable length about the imperialism of the Ottoman Empire. Some of the populations directly conquered by them hold a grudge. Others don’t hold a grudge in large part because their territory went directly from being Ottoman colonial possessions to being British or French colonial possessions, so they just transferred their grudges to whichever empire had actually existed within living memory.

In other words, plenty of people are prepared to call the Ottomans imperialist (or things worse than that), and plenty of the people who don’t are only doing so because someone else swooped in and redirected their attention to an entirely different set of oppressors.

I don’t see either what your supporting evidence is for the sweeping claim you make about modern historiography, or what your point is in making the claim in the first place. What is the actual conclusion you are supporting with this assertion?

Can’t speak for ad-numbers, whose username definitely doesn’t make them sound like a burner account, but… When I hear that sort of argument in the wild, it’s usually supporting (or at least adjacent to) the idea that SJWs are using historical revisionism to demonize Europe’s superior culture.

And I get that sort of feeling from ad. “We don’t call Ottomans colonizers because they were minorities attacking whites instead of the other way around.”

“I think that an honest review of the literature in Europe regarding the Ottoman Empire, over the past several hundred years and including the present day, would suggest otherwise.”

Professional literature, maybe. Although I would very much appreciate if you could point out relevant literature where, say, the Balkan wars in the late 19th and early 20th century are discussed in the context of decolonization, ’cause I’m not aware of any. But in popular culture and contemporary politics, the Ottomans’ conquests are definitely NOT viewed as colonizing. Imperialist, maybe – although large parts of western popular culture and political though tend to see the Ottomans as too “barbaric” to be accepted as bona fide imperialists – but definitely not colonialist.

A quick google search confirms that: searching for “decolonization of the Balkans” yields only a fraction of mostly obscure references compared to, say, decolonization of Africa.

Apologies. To clarify, what I was getting at is that there is an ample tradition in Western literature and history of dwelling on the assorted cruelties, vices, oppressions, and torments inflicted on Christians and ‘the West’ by the Ottomans.*

There is no shortage of that. It is not something “the West” has somehow forgotten any more than it’s forgotten dozens of other bits of imperial domination, and frankly less.

I’m not so much thinking of professional literature in the modern day specifically analyzing the breakup of the Ottomans in the Balkans in the 19th century as “decolonization.”

I’m addressing the broader point that there isn’t actually some kind of leftist ‘intellectual elite’ plot to make ‘the West’ effete and vulnerable to Islam by quietly memory-holing the VERY IMPORTANT fact that 150 years ago there was a Muslim government ruling over (GASP) a significant chunk of CHRISTIAN!!! Europe.

Which is the insinuation I’m sensing from the post I was originally responding to.

________________________

*(The assorted abuses are sometimes real, sometimes the product of Orientalizing imagination; the Ottomans could be nasty customers and I’m not denying it for a minute)

Apologies. To clarify, what I was getting at is that there is an ample tradition in Western literature and history of dwelling on the assorted cruelties, vices, oppressions, and torments inflicted on Christians and ‘the West’ by the Ottomans.*