Thanks to our volunteer narrator, this post is now available in audio format.

This week, in an effort to fill in some of the theoretical basis for thinking about how weaker powers think about fighting against or defending themselves from stronger powers, I’m going to give you all a basic 101-level survey of the theory of protracted war (also called People’s War), which tends to be one of the main frameworks military thinkers – both in powerful countries and weaker ones – use to think about strategies for this kind of conflict.

Of course the context here is the on-going1 conflict in Ukraine, where a weaker power (Ukraine) is fighting for its independence from the unprovoked aggression of a stronger power (Russia). So at the end, I will say a few very general words about what I think the theory we discuss means for the conflict in Ukraine, the approach the Ukrainian military is taking, and some of the ways they may evolve their defense as Russian forces continue their assault.

But first, and I want to emphasize this very clearly, perhaps more than most kinds of war, protracted war is very much shaped by local conditions and so has to be highly modified to fit those conditions. So do not treat this as a model for operations but as a framework for thinking about what the weaker power is trying to accomplish and how they can accomplish that despite being weaker. This is a ‘way of thinking’ that has to be molded to fit the local population, local politics, local terrain and the relative capabilities of the belligerents (as well as, as we’ll see, changing technology).

And once again before we get started, a reminder that the conflict in Ukraine is not notional or theoretical but very real and is causing very real suffering, including displacing large numbers of Ukrainians as refugees, both within Ukraine and beyond its borders. If you want to help, consider donating to Ukrainian aid organizations like Razom for Ukraine or to the Ukrainian Red Cross. As we’re going to see this week, there is unfortunately a high likelihood that this war will continue for some time and so both Ukrainian refugees forced from their country and Ukrainians still under threat in Ukraine will need international support to provide food, medical supplies and other essentials.

On with our topic: how do you win a war against a powerful, industrialized enemy when you are not a powerful, industrialized state?

Mao’s Theory of Protracted War

The foundation for most modern thinking about this topic begins with Mao Zedong’s2 theorizing about what he called ‘protracted people’s war‘ in a work entitled – conveniently enough – On Protracted War (1938), though while the Chinese Communist Party would tend to subsequently represent the ideas there are a singular work of Mao’s genius, in practice he was hardly the sole thinker involved. The reason we start with Mao is that his subsequent success in China (though complicated by other factors) contributed to subsequent movements fighting ‘wars of national liberation’ consciously modeled their efforts off of this theoretical foundation.

The situation for the Chinese Communists in 1938 was a difficult one. The Chinese Red Army has set up a base of power in the early 1930s in Jiangxi province in South-Eastern China, but in 1934 had been forced by Kuomintang Nationalist forces under Chiang Kai-shek to retreat, eventually rebasing over 5,000 miles away (they’re not able to straight-line the march) in Shaanxi in China’s mountainous north in what became known as The Long March. Consequently, no one could be under any illusions of the relative power of the Chiang’s nationalist forces and the Chinese Red Army. And then, to make things worse, in 1937, Japan had invaded China (the Second Sino-Japanese War, which was a major part of WWII), beating back the Nationalist armies which had already shown themselves to be stronger than the Communists. So now Mao has to beat two armies, both of which have shown themselves to be much stronger than he is (though in the immediate term, Mao and Chiang formed a ‘United Front’ against Japan, though tensions remained high and both sides expected to resume hostilities the moment the Japanese threat was gone). Moreover, Mao’s side lacks not only the tools of war, but the industrial capacity to build the tools of war – and the previous century of Chinese history had shown in stark terms how difficult a situation a non-industrial force faced in squaring off against industrial firepower.

That’s the context for the theory.

What Mao observed was that a “war of quick decision” would be one that the Red Army would simply lose. Because he was weaker, there was no way to win fast, so trying to fight a ‘fast’ war would just mean losing. Consequently, a slow war – a protracted war – was necessary. But that imposes problems – in a ‘war of quick decision’ the route to victory was fairly clear: destroy enemy armed forces and seize territory to deny them the resources to raise new forces. Classic Clausewitzian (drink!) stuff. But of course the Red Army couldn’t do that in 1938 (they’d just lose), so they needed to plan another potential route to victory to coordinate their actions. That is, they need a strategic framework – remember that strategy is the level of military analysis where we think about what our end goals should be and what methods we can employ to actually reach those goals (so that we are not just blindly lashing out but in fact making concrete progress towards a desired end-state).

Mao understands this route as consisting of three distinct phases, which he imagines will happen in order as a progression and also consisting of three types of warfare, all of which happen in different degrees and for different purposes in each phase. We can deal with the types of warfare first:

- Positional Warfare is traditional conventional warfare, attempting to take and hold territory. This is going to be done generally by the regular forces of the Red Army.

- Mobile Warfare consists of fast-moving attacks, ‘hit-and-run,’ performed by the regular forces of the Red Army, typically on the flanks of advancing enemy forces.

- Guerrilla Warfare consists of operations of sabotage, assassination and raids on poorly defended targets, performed by irregular forces (that is, not the Red Army), organized in the area of enemy ‘control.’

The first phase of this strategy is the enemy strategic offensive (or the ‘strategic defensive’ from the perspective of Mao). Because the enemy is stronger and pursuing a conventional victory through territorial control, they will attack, advancing through territory. In this first phase, trying to match the enemy in positional warfare is foolish – again, you just lose. Instead, the Red Army trades space for time, falling back to buy time for the enemy offensive to weaken rather than meeting it at its strongest, a concept you may recall from our discussions of defense in depth. The focus in this phase is on mobile warfare, striking at the enemy’s flanks but falling back before their main advances. Positional warfare is only used in defense of the mountain bases (where terrain is favorable) and only after the difficulties of long advances (and stretched logistics) have weakened the attacker. Mobile warfare is supplemented by guerrilla operations in rear areas in this phase, but falling back is also a key opportunity to leave behind organizers for guerrillas in the occupied zones that, in theory at least, support the retreating Red Army (we’ll come back to this).

Eventually, due to friction (drink!) any attack is going to run out of steam and bog down; the mobile warfare of the first phase is meant to accelerate this, of course. That creates a second phase, ‘strategic stalemate’ where the enemy, having taken a lot of territory, is trying to secure their control of it and build new forces for new offensives, but is also stretched thin trying to hold and control all of that newly seized territory. Guerrilla attacks in this phase take much greater importance, preventing the enemy from securing their rear areas and gradually weakening them, while at the same time sustaining support by testifying to the continued existence of the Red Army. Crucially, even as the enemy gets weaker, one of the things Mao imagines for this phase is that guerrilla operations create opportunities to steal military materiel from the enemy so that the factories of the industrialized foe serve to supply the Red Army – safely secure in its mountain bases – so that it becomes stronger. At the same time (we’ll come back to this), in this phase capable recruits are also be filtered out of the occupied areas to join the Red Army, growing its strength.

Finally in the third stage, the counter-offensive, when the process of weakening the enemy through guerrilla attacks and strengthening the Red Army through stolen supplies, new recruits and international support (Mao imagines the last element to be crucial and in the event it very much was), the Red Army can shift to positional warfare again, pushing forward to recapture lost territory in conventional campaigns.

Through all of this, Mao stresses the importance of the political struggle as well. For the guerrillas to succeed, they must “live among the people as fish in the sea.” That is, the population – and in the China of this era that meant generally the rural population – becomes the covering terrain that allows the guerrillas to operate in enemy controlled areas. In order for that to work, popular support – or at least popular acquiescence (a village that doesn’t report you because it supports you works the same way as a village that doesn’t report you because it hates Chiang or a village that doesn’t report you because it knows that it will face violence reprisals if it does; the key is that you aren’t reported) – is required. As a result both retreating Red Army forces in Phase I need to prepare lost areas politically as they retreat and then once they are gone the guerrilla forces need to engage in political action. Because Mao is working with a technological base in which regular people have relatively little access to radio or television, a lot of the agitation here is imagined to be pretty face-to-face, or based on print technology (leaflets, etc), so the guerrillas need to be in the communities in order to do the political work.

Guerrilla actions in the second phase also serve a crucial political purpose: they testify to the continued existence and effectiveness of the Red Army. After all, it is very important, during the period when the main body of Communist forces are essentially avoiding direct contact with the enemy that they not give the impression that they are defeated or have given up in order to sustain will and give everyone the hope of eventual victory. Everyone there of course also includes the main body of the army holed up in its mountain bases – they too need to know that the cause is still active and that there is a route to eventual victory.

Fundamentally, the goal here is to make the war about mobilizing people rather than about mobilizing industry, thus transforming a war focused on firepower (which you lose) into a war about will – in the Clausewitzian (drink! – folks, I hope you all brought more than one drink for this…) sense – which can be won, albeit only slowly, as the slow trickle of casualties and defeats in Phase II steadily degrades enemy will, leading to their weakness and eventual collapse in Phase III.

I should note that Mao is very open that this protracted way of war would be likely to inflict a lot of damage on the country and a lot of suffering on the people. Casualties, especially among the guerrillas, are likely to be high and the guerrillas own activities would be likely to produce repressive policies from the occupiers (not that either Chiang’s Nationalists of the Imperial Japanese Army – or Mao’s Communists – needed much inducement to engage in brutal repression). Mao acknowledges those costs but is largely unconcerned by them, as indeed he would later as the ruler of a unified China be unconcerned about his man-made famine and repression killing millions. But it is important to note that this is a strategic framework which is forced to accept, by virtue of accepting a long war, that there will be a lot of collateral damage.

Now there is a historical irony here: in the event, Mao’s Red Army ended up not doing a whole lot of this. The great majority of the fighting against Japan in China was positional warfare by Chiang’s Nationalists; Mao’s Red Army achieved very little (except preparing the ground for their eventual resumption of war against Chiang) and in the event, Japan was defeated not in China but by the United States. Japanese forces in China, even at the end of the war, were still in a relatively strong position compared to Chinese forces (Nationalist or Communist) despite the substantial degradation of the Japanese war economy under the pressure of American bombing and submarine warfare. But the war with Japan left Chiang’s Nationalists fatally weakened and demoralized, so when Mao and Chiang resumed hostilities, the former with Soviet support, Mao was able to shift almost immediately to Phase III, skipping much of the theory and still win.

Nevertheless, Mao’s apparent tremendous success gave his theory of protracted war incredible cachet, leading it to be adapted with modifications (and variations in success) to all sorts of similar wars, particularly but not exclusively by communist-aligned groups.

Adapting the Theory

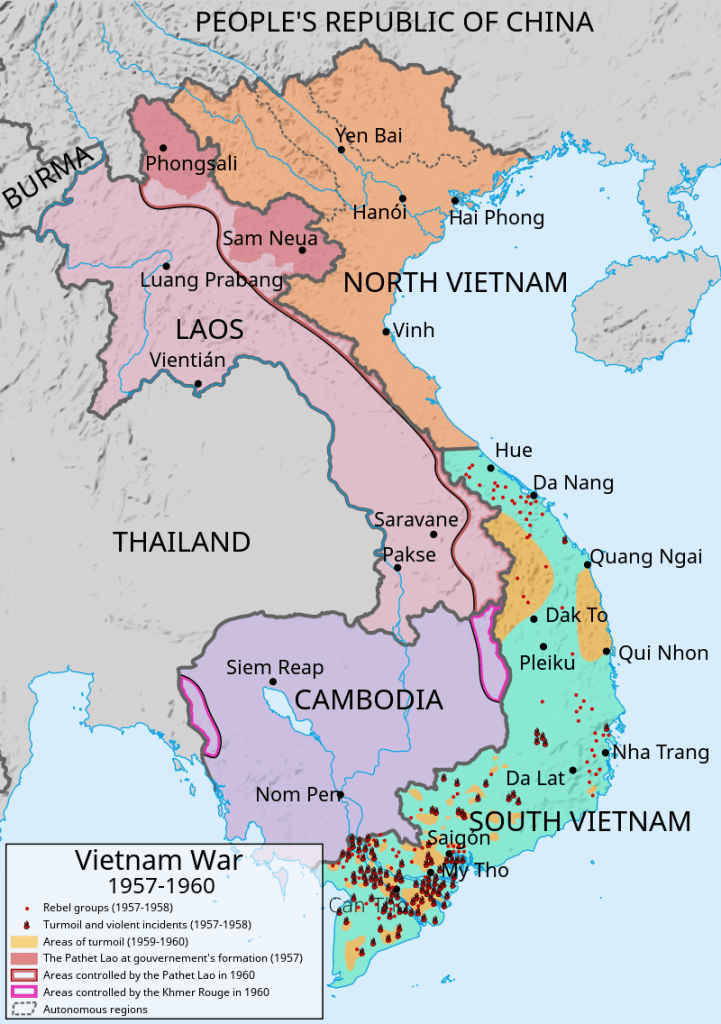

As I noted at the outset, this sort of theory has to be heavily adapted to work in different places. We can get a sense of how those adaptations can work by looking, briefly, at a few of them. One of the most important of these cases to study is Vietnam.

The primary architect of Vietnam’s strategy, initially against French colonial forces and then later against the United States and the US backed South Vietnamese (Republic of Vietnam or RVN) government was Võ Nguyên Giáp.

Giáp was facing a different set of challenges in Vietnam facing either France or the United States which required the framework of protracted war to be modified. First, it must have been immediately apparent that it would never be possible for a Vietnamese-based army to match the conventional military capability of its enemies, pound-for-pound. Mao could imagine that at some point the Red Army would be able to win an all-out, head-on-head fight with the Nationalists, but the gap between French and American capabilities and Vietnamese Communist capabilities was so much wider.

At the same time, trading space for time wasn’t going to be much of an option either. China, of course, is a very large country, with many regions that are both vast, difficult to move in, and sparsely populated. It was thus possible for Mao to have his bases in places where Nationalist armies literally could not reach. That was never going to be possible in Vietnam, a country in which almost the entire landmass is within 200 miles of the coast (most of it is far, far less than that) and which is about 4% the size of China.

So the theory is going to have to be adjusted, but the basic groundwork – protract the war, focus on will rather than firepower, grind your enemy down slowly and proceed in phases – remains.

I’m going to need to simplify here, but Giáp makes several key alterations to Mao’s model of protracted war. First, even more than Mao, the political element in the struggle was emphasized as part of the strategy, raised to equality as a concern with the military side and fused with the military operation; together they were termed dau tranh, roughly “the struggle.” Those political activities were divided into three main components. Action among one’s own people consisted of propaganda and motivation designed to reinforce the will of the populace that supported the effort and to gain recruits. Then, action among the enemy people – here meaning Vietnamese who were under the control of the French colonial government or South Vietnam and not yet recruited into the struggle – a mix of propaganda and violent action to gain converts and create dissension. Finally, action against the enemy military, which consisted of what we might define as terroristic violence used as message-sending to negatively impact enemy morale and to encourage Vietnamese who supported the opposition to stop doing so for their own safety.

Part of the reason the political element of this strategy was so important was that Giáp knew that casualty ratios, especially among guerrilla forces – on which, as we’ll see, Giáp would have to rely more heavily – would be very unfavorable. Thus effective recruitment and strong support among the populace was essential not merely to conceal guerrilla forces but also to replace the expected severe losses that came with fighting at such a dramatic disadvantage in industrial firepower.

That concern in turn shaped force-structure. Giáp theorized an essentially three-tier system of force structure. At the bottom were the ‘popular troops,’ essentially politically agitated peasants. Lightly armed, minimally trained but with a lot of local knowledge about enemy dispositions, who exactly supports the enemy and the local terrain, these troops could both accomplish a lot of the political objectives and provide information as well as functioning as local guerrillas in their own villages. Casualties among popular troops were expected to be high as they were likely to ‘absorb’ reprisals from the enemy for guerrilla actions. Experienced veterans of these popular troops could then be recruited up into the ‘regional troops,’ trained more who could now be deployed away from their home villages as full-time guerrillas, and in larger groups. While popular troops were expected to take heavy casualties, regional troops were carefully husbanded for important operations or used to organize new units of popular troops. Collectively these two groups are what are often known in the United States at the Viet Cong, though historians tend to prefer their own name for themselves, the National Liberation Front (Mặt trận Dân tộc Giải phóng miền Nam Việt Nam, “National Liberation Front for South Vietnam) or NLF. Finally, once the French were forced to leave and Giáp had a territorial base he could operate from in North Vietnam, there were conventional forces, the regular army – the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) – which would build up and wait for that third-phase transition to conventional warfare.

The greater focus on the structure of courses operating in enemy territory reflected Giáp’s adjustment of how the first phase of the protracted war would be fought. Since he had no mountain bases to fall back to, the first phase relied much more on political operations in territory controlled by the enemy and guerrilla operations, once again using the local supportive population as the cover to allow guerrillas and political agitators (generally the same folks, cadres drawn from the regional troops to organize more popular troops) to move undetected. Guerrilla operations would compel the less-casualty-tolerant enemy to concentrate their forces out of a desire for force preservation, creating the second phase strategic stalemate and also clearing territory in which larger mobile forces could be brought together to engage in mobile warfare, eventually culminating in a shift in the third phase to conventional warfare using the regional and regular troops.

Finally, unlike Mao, who could envision (and achieve) a situation where he pushed the Nationalists out of the territories they used to recruit and supply their armies, the Vietnamese Communists had no hope (or desire) to directly attack France or the United States. Indeed, doing so would have been wildly counter-productive as it likely would have fortified French or American will to continue the conflict.

That limitation would, however, demand substantial flexibility in how the Vietnamese Communists moved through the three phases of protracted war. This was not something realized ahead of time, but something learned through painful lessons. Leadership in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV = North Vietnam) was a lot more split than among Mao’s post-Long-March Chinese Communist Party; another important figure, Lê Duẩn, who became general secretary in 1960, advocated for a strategy of “general offensive” paired with a “general uprising” – essentially jumping straight to the third phase. The effort to implement that strategy in 1964 nearly overran the South, with ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam – the army of South Vietnam) being defeated by PAVN and NLF forces at the Battles of Bình Giã and Đồng Xoài (Dec. 1964 and June 1965, respectively), but this served to bring the United States more fully into the war – a tactical and operational victory that produced a massive strategic setback.

Lê Duẩn did it again in 1968 with the Tet Offensive, attempting a general uprising which, in an operational sense, mostly served to reveal NLF and PAVN formations, exposing them to US and ARVN firepower and thus to severe casualties, though politically and thus strategically the offensive ended up being a success because it undermined American will to continue the fight. American leaders had told the American public that the DRV and the NLF were largely defeated, broken forces – the sudden show of strength exposed those statements as lies, degrading support at home. Nevertheless, in the immediate term, the Tet Offensive’s failure on the ground nearly destroyed the NLF and forced the DRV to back down the phase-ladder to recover. Lê Duẩn actually did it again in 1972 with the Eastern Offensive when American ground troops were effectively gone, exposing his forces to American airpower and getting smashed up for his troubles.

It is difficult to see Lê Duẩn’s strategic impatience as much more than a series of blunders – but crucially Giáp’s framework allowed for recovery from these sorts of defeats. In each case, the NLF and PAVN forces were compelled to do something Mao’s model hadn’t really envisaged, which was to transition back down the phase system, dropping back to phase II or even phase I in response to failed transitions to phase III. By moving more flexibly between the phases (while retaining a focus on the conditions of eventual strategic victory), the DRV could recover from such blunders. I think Wayne Lee3 actually puts it quite well that whereas Mao’s plan relied on “many small victories” adding up to a large victory (without the quick decision of a single large victory), Giáp’s more flexible framework could survive many small defeats on the road to an eventual strategic victory when the will of the enemy to continue the conflict was exhausted.

Of course that focus on will relied on the assumption that the weaker force ‘wants to win more’ than the stronger one. Which is of course not always true and it seems worth noting here again that most insurgencies fail. In the absence of robust popular support, efforts to use this or similar frameworks (such as Che Guevara’s foquismo, which to be frank I generally find as a less compelling, less capable variant of these ideas) often fail quite badly (as, indeed, Che Guevara’s own efforts failed in the Congo and in Bolivia). Governments faced by insurgencies are often able to justify their use of force based on the violent actions of guerrillas, thus preserving their own will. At the same time, it is much easier to convince a foreign force that occupying a country is no longer worth it than to convince a state with any meaningful base of support to abolish itself. Protracted war is thus far, far from an unbeatable strategy.

The strategy pursued by the Taliban in Afghanistan has followed similar lines, with the mountains of the Hindu Kush on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border serving as the equivalent of Mao’s mountain bases. The Taliban practiced a propaganda strategy not too dissimilar from Giáp’s, using terroristic violence and targeted assassinations to persuade (by the threat of violence) the population to support them or at least remain neutral while at the same time those acts – often dramatic and publicized after the fact – served as proof to members that the organization was making progress (think ‘testify to the continued existence of the Red Army’). The use by the Taliban of modern media to do their propaganda work both in country and abroad is a notable technological adaptation of the model (something that of course was also used very heavily by ISIS).

Because the Taliban couldn’t really target American industrial might – as Giáp couldn’t – American will was focused on instead. Modern insurgencies also often use their attacks to try to lure their more powerful opponents into applying excessive firepower, thereby doing their propaganda for them (on this, read W. Morgan, The Hardest Place (2021) for just how easy it is for a Big Firepower military with lots of powerful air support to fall into this trap again and again. Also, if you read it with an eye towards the three phases of protracted war, you will find all three without much difficulty). At the same time, the Taliban clearly accepted that this would be a protracted, slow war but concluded they were more willing to stick it out than the United States was, despite a stunningly lopsided unfavorable casualty ratio. And then of course, at the end, once the United States was gone, they shifted to phase III and waged a successful conventional campaign of territorial control against the fatally weakened Afghan government.

One thing that is very striking in all of these examples was the importance of outside support. While Mao mentions outside support, he envisages most of the equipment of the reinforced Red Army as coming from equipment taken from the enemy. But in practice, in all of these cases, outside support, particularly the provision of weapons and safe bases, was crucial for the success of the protracted war strategy; getting weapons and equipment from the enemy was never as effective as having a foreign sponsor who could provide them. That, of course, imposes an additional political dimension to a protracted war: the need to maintain foreign support either by ideological conformity or through active propaganda on the world stage or both. Again, that’s in Mao’s original theory, but it is not emphasized to nearly the degree of prominence that it tends to hold in actual efforts at protracted war.

Boiling Down the Theory

What I hope these different examples show clearly is how the strategy of protracted war has to be adapted for local circumstances and new communications technologies and the ways in which it can be so adapted. But before we talk about how the framework might apply to the current conflict in Ukraine (the one which resulted from Russia’s unprovoked, lawless invasion), I want to summarize the basic features that connect these different kinds of protracted war.

First, the party trying to win a protracted war accepts that they are unable to win a “war of quick decision” – because protracted war tends to be so destructive, if you have a decent shot at winning a war of quick decision, you take it. I do want to stress this – no power resorts to insurgency or protracted war by choice; they do it out of necessity. This is a strategy of the weak. Next, the goal of protracted war is to change the center of gravity of the conflict from a question of industrial and military might to a question of will – to make it about mobilizing people rather than industry or firepower. The longer the war can be protracted, the more opportunities will be provided to degrade enemy will and to reinforce friendly will (through propaganda, recruitment, etc.).

Those concerns produce the ‘phase’ pattern where the war proceeds – ideally – in stages, precisely because the weaker party cannot try for a direct victory at the outset. In the first phase, it is assumes the stronger party will try to use their strength to force that war of quick decision (that they win). In response, the defender has to find ways to avoid the superior firepower of the stronger party, often by trading space for time or by using the supportive population as covering terrain or both. The goal of this phase is not to win but to stall out the attacker’s advance so that the war can be protracted; not losing counts as success early in a protracted war.

That success produces a period of strategic stalemate which enables the weaker party to continue to degrade the will of their enemy, all while building their own strength through recruitment and through equipment supplied by outside powers (which often requires a political effort directed at securing that outside support). Finally, once enemy will is sufficiently degraded and their foreign partners have been made to withdraw (through that same erosion of will), the originally weaker side can shift to conventional ‘positional’ warfare, achieving its aims.

This is the basic pattern that ties together different sorts of protracted war: protraction, the focus on will, the consequent importance of the political effort alongside the military effort, and the succession of phases.

(For those who want more detail on this and also more of a sense of how protracted war, insurgency and terrorism interrelate as strategies of the weak, when I cover this topic in the military history survey, the textbook I use is W. Lee, Waging War: Conflict, Culture and Innovation in World History (2016). Chapter 14 covers these approaches and the responses to them and includes a more expensive bibliography of further reading. Mao’s On Protracted War can be found translated online. Many of Giáp’s writings on military theory are translated and gathered together in R. Stetler (ed.), The Military Art of People’s War: Selected Writings of General Vo Nguyen Giap (1970).)

Implications for Ukraine

Of course the reason for discussing this now is that I think that this framework bears on how to understand the pathways that Ukraine may have to victory or at least limiting the objectives the Russian Armed Forces can achieve. Fundamentally, Ukraine faces many of the same constraints that led to the use of protracted war. Despite scoring many smaller victories in the opening days of the Russian invasion, the Ukrainian army has little hope in the forseeable future of being able to fight and defeat the Russian army in ‘open battle’ outside of urban areas. While the Ukraine has done a stunning job contesting the air, there is no question that Russia has the advantage in airpower and in fires4 more generally. If Ukraine attempted to maneuver in large formations in the open on the offensive (the way Russia is currently doing) it seems almost certain that the Russian superiority in fires would quickly extract a terrible toll. Ukraine also has no direct 5 way of striking at the Russian means of waging war – the industrial base that produces and maintains Russian firepower.

Thus, in a “war of quick decision” it seems very likely – even given so far the surprising success and tremendous heroism of the Ukrainians – that Ukraine would lose. To win, Ukraine has to protract the war, working on the assumption that they ‘want to win more’ than Russia does (be that Russia defined as Vladimir Putin, or as his major supporters, or as the soldiers on the front line themselves; breaking the will of any of these three might be enough to compel Russia to terminate hostilities). Thus the Ukrainian efforts in the war need to be focused as much on will – both reinforcing their own will and degrading the will of the enemy – as on battlefield victories.

Yet the Ukrainian situation is also different. Ukraine is a complete state and thus has access to some significant modern industrialized firepower. Through international actors, they have access to even more. The terrain is also different too. Ukraine does not have jungles (it does have some mountains), but rather is mostly fairly flat and open, divided by one very large river (and many small ones). While Ukraine is a very large country, there would normally be little doubt that Russian forces could project power from one end to the other (although this may need qualification given Russian logistics failures, but note that no part of Ukraine is very far from a potential Russian logistics base, be it in Russia, Crimea or Belarus). Terrain is not going to stop Russian forces in the absence of effective resistance for very long.6 The Ukrainian army thus cannot retreat forever into functionally impassable terrain the way Mao’s army could.

Red zones indicate areas of Russian or separatist control, red lines indicate Russian advances. I prefer Ruser’s map here because it expresses a truth about the current situation, which is that Russia is not so much expanding areas of control as they are driving lines of movement into Ukraine. We haven’t seen yet Russian forces begin to administer areas they’ve ‘taken’ or secure gains.

Nevertheless, much of the model of protracted war applies. We are fairly clearly in the first phase – the enemy’s strategic offensive. Russia advances everywhere – in some places faster, in many places much slower. Going by the theory of protracted war, the Ukrainian aim ought not to be to force a decisive battle at any one point, but rather to exhaust the Russian advance, while preserving as much of their forces as possible. In our theory, that means working to accelerate the breakdown of the Russian offensive which allows the transition from phase I to phase II.

There is a lot of fog of war here but given what we can see, you can just about make out the outlines of that kind of phase I strategy in practice. Ukrainian forces so far have generally fallen back to force engagements in urban areas where the built up terrain provides cover from Russian firepower. Urban warfare trends to soak up tremendous amounts of soldiers and materiel, so forcing the Russian army into a series of difficult sieges is likely to be an effective way to exhaust their offensive more rapidly. At the same time, in the South, where the terrain is less favorable, Ukrainian units have generally withdrawn. It seems notable that Ukrainian forces in Kherson inflicted losses on the Russian advance but seem to have withdrawn from the city before the Russians could encircle it or deliver a crushing final assault (but note the contrast in the North where Kharkiv and Kyiv are more strongly held, in part one assumes because they are likely to be more defensible). At the same time, where the Ukrainians have counter-attacked, the strikes tend to be not into the heads of Russian advances but into the flanks of large convoys and look designed to slow or prevent the encirclement of major cities to further bog down the Russian advance – something fairly easy to classify as ‘mobile warfare’ in Mao’s model.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian attacks appear to be prioritizing targets of opportunity, especially Russian logistics. Cargo trucks like the Ural-4320, -43206, and the KamAZ 6×6 make up a high proportion of confirmed Russian vehicle losses; most of the footage of drone strikes (using the Bayraktar TB2 Turkish drone) also seem to be on rear echelon units or units still moving into the combat zone. In many ways this seems like a modern application of the mobile warfare Mao envisaged in the first phase, using drones, indirect fires and infantry with man-portable weapons (that can be moved off-road or hidden) to inflict damage on the ‘tail’ of the Russian army, rather than its teeth.

The potential for urban sieges, while horrifying from a humanitarian perspective, also offers the potential for the Ukrainians to speed the transition to phase II (strategic stalemate) while they still hold much of the country. If Russian advances bog down into a long series of sieges of major cities (Kyiv and Kharkiv, but also potentially Dnipro and Zaporizhzhia) that may essentially create the conditions of the strategic stalemate, where the Russian advance is stopped as Russian forces attempt to pound these cities into submission – a task which, as we’ve seen in conflicts in Syria and Iraq – can take months or even years. Meanwhile, though I doubt the Ukrainians will see the issue this way, Russian frustration at not being able to take these cities is already luring them into the over-application of force trap we just discussed: indiscriminate Russian fires into civilian areas may both harden Ukrainian resolve and galvanize world opinion.

I do want to be very clear here: the War in Ukraine may end up transitioning into either a series of urban sieges, or an insurgency (either over the whole country or, as now seems more likely, in rear areas behind the Russian front lines). Both kinds of fighting raise the likelihood of increased destruction and civilian casualties; protracted war, because it is protracted, is typically very destructive and precisely because civilians often become the covering terrain for the defenders, they are often targeted with repression or violence. Russian forces have typically responded to urban sieges with indiscriminate shelling and have also generally responded to insurgency with repression and violence. So I want to be clear, I fear the transition to this kind of fighting and I hope that it isn’t necessary, but I also suspect that warfare of this sort may be the only road that leads to eventual Ukrainian victory. It is also frankly utterly backwards to suggest that Ukraine ought to just roll over so that Russia does not commit war crimes and human rights violations; Russia should obey the laws of armed conflict and it is not Ukraine’s responsibility to make things easy for them so they don’t get frustrated and do some war crimes in the midst of their illegal and unprovoked invasion. It is of course Russia that could avoid all of this suffering by not continuing an unprovoked invasion into another country. If they weren’t there, they wouldn’t be there.

Perhaps the clearest evidence that the Ukrainians are waging a protracted war is exactly is the attention to the information war, to a much greater degree and far more initial success than Russia. As with the political strategies of dau tranh, the Ukrainians have different messages to different groups: they need to harden Ukrainian resolve, they need to try to galvanize world opinion, they need to weaken Russian resolve. Managing those different messages can be difficult – advertising Russian casualties, for instance, might lower morale on the front lines, but could harden resolve at home and might backfire with the international community (the Ukrainian solution seems to have been to focus on destroyed equipment to stress enemy losses and living Russian prisoners who are shown to be well treated; it’s a savvy strategy). Nevertheless, Ukraine has showed tremendous skill in managing their messaging, while Russia has been caught completely flatfooted.

Drone warfare also provides an interesting opportunity in this context, and we’ve seen the Ukrainians using it for tactical, operational and strategic effects. The tactical effect is obvious: armed drones can inflict damage. Operationally, as noted, drone strikes have tended to target units in transit and logistics, ‘interdiction strikes,’ which make it more difficult for Russian forces to move rapidly. Strategically, Ukraine is using drones where another force might have used terroristic violence – a strategy which, because Ukraine needs global support, they cannot use openly – to testify to the continued existence and effectiveness of the Blue-and-Yellow Army. If, as I fear, the war becomes a series of sieges, this use of drones is likely to become more important – Ukrainian soldiers and civilians being shelled inside of besieged cities are going to want to know that they are striking back somehow. Drone footage of strikes against expensive Russian military equipment – including potentially the very artillery shelling the cities – can mitigate the ‘will-damage’ as it were, of these sieges. This of course dovetails with the information war and explains why, for instance, there is already a catchy Ukrainian song7 praising their drone of choice, the Turkish made Bayraktar TB2 (a UCAV, “unmanned combat aerial vehicle” which already proved its considerable effectiveness in the Azerbaijan-Amernian war over Nagorno-Karabakh in 2020).

Finally, it is precisely in a context of a protracted war that the expensive, stiff sanctions that much of the rest of the world has placed on Russia matter. Putin, I suspect, hoped that he could win this war quickly, after which he could present the sanctions – which I also very strongly suspect he thought would be far weaker than they have been – as useless and counter-productive, damaging the economies of NATO member states. But the longer Ukraine can protract the war, the longer those sanctions have time to degrade not only the will, but also the military capacity of Russia. In this sense, Ukraine actually can, indirectly, through world opinion, strike at the industrial base which powers the Russian war effort. Consequently, since both Ukrainian war-making capabilities (due to foreign weapon donations) and Russian war-making capabilities (due to the crippling effects of sanctions) in the long-run depend on international will and support, Ukraine has to wage their war with a lot of attention to global opinion; Russia had to do this too and it is fair to say they failed before they knew they needed to care. The longer the war is protracted, the more that global opinion will matter, as the sanctions and imported javelins and Bayraktar TB2s bite deeper.

Protracted war also poses risks and costs, however. The costs I’ve hinted at several times but let’s be explicit: precisely because the war is protracted, the damage to civilian infrastructure, the disruption to civilian life and the loss of civilian life is likely to be higher. This is a strategy that aims to make the war about mobilizing people rather than mobilizing industry and firepower and when people are your center of gravity, then that is where the enemy will try to strike. Consequently, we may see efforts – even at a low probability of success – for Ukraine to try to engage in early positional warfare.

Moreover, a strategy of protracted war is going to demand that the Ukrainians preserve their army and leadership, even if it means giving up territory and even if it means leaving civilians, for a time, under a Russian occupation that may – as the violence escalates – become increasingly brutal and repressive. A state or a people only resorts to protracted war because they have no other options; this is a strategy of the weak – and Ukraine is, compared to Russia, still the weaker party. Preserving the leadership core of the Ukrainian state and some part of the army is going to be essential for continued resistance if Russian forces continue pushing forward as they have been.

Preserving that core is in turn going to in turn pose terrible choices on Ukraine’s leaders. On the one hand, they want to stand with their country, but on the other hand at least some part of the government needs to survive to coordinate resistance and provide something for it to rally around; this problem will get especially acute if the encirclement of Kyiv is completed. Meanwhile, Ukrainian armed forces are eventually going to have to withdraw in some areas – particularly from positions along the line of contact in the Donbas – to avoid being either encircled or forced into a conventional battle of ‘quick decision.’ Retreating from contact always entails casualties but also political costs as territory is left to the enemy, but in a protracted war, it is unavoidable.

In conclusion, a protracted war in Ukraine is a terrible prospect, but it may be the only route the Ukrainians have that ends in victory if Putin’s invasion continues, as still seems likely. From my own position, it looks like the early Ukrainian successes have put them in a fairly strong position should the war become protracted as they look likely to hold much of their country, have galvanized world opinion, and have difficult-to-assault urban centers to use as defensive bulwarks. At the same time, as the Russian Armed Forces respond to this strategy by increasingly shelling and bombing civilian centers, the level of civilian casualties and collateral damage are likely to rise and the very nature of protracted war means that those tragedies are unlikely to stop any time soon.

I wish I had better news, but hopefully this theory overview will help to understand how the conflict in Ukraine may evolve and what victory may look like for Ukraine. Next week we’re going to instead turn to another question that has been burning up social media – nuclear weapons and how nuclear deterrence works.

- as I write this; I dearly hope, reader from the future, that when you read this, Ukraine is free, independent and at peace

- In case it needs saying, I’m not idolizing Mao here. His theory is important for reasons we’ll discuss, even if Mao himself was an abominable human being and the ideology which he fought for was also fundamentally bankrupt and mostly just inflicted additional unnecessary suffering on the Chinese people.

- Work cited below

- Artillery, airstrikes, cruise missiles, etc.

- Important word! See below

- And before anyone rushes into the comments to note the 40-mile-long convoy and other dramatic Russian logistics failures, do not that the Ukrainians are in fact doing quite a lot to ‘help’ those failures along, destroying key bridges, blocking roads and denying key crossroads that are within urban centers. Unobstructed, Russian soldiers in a truck could drive across the whole of Ukraine in about two days, with time to get a good night’s sleep somewhere on the Dnieper in the middle. Of course they are not unobstructed and that is the key.

- Tell me that won’t be stuck in your head for the next hour. Also notice how it is something that isn’t too difficult to sing along to (if you speak Ukrainian)? I wonder if that is intentional – something that Ukrainians can both listen to but literally sing along with to keep their spirits up as they shelter from Russian shelling.

The examples of ultimate success by the weaker party in a protracted war, that you reference, all involved quasi-religious movements, directed by a self selected elite.

Is there any example of a weaker party winning a protracted war that lacks either of those characteristics? IE some large ideological framework which people will willingly risk their lives for. And a not exactly tyrannical but closer to than than democratic, elite, willing to sacrifice some large number of their people’s lives to achieve ultimate victory?

I can’t think of any.

Both the Chinese Communists and Vietnamese Communists would be deeply offended by being labelled as religious or quasi-religious. In practice neither movement could be 100% atheist as Marxist doctrine required, but the ideology and motivation was very modern.

(And no I’m not saying Mao didn’t try for religious leader status. But that came more after they’d won?)

And my impression is that guerrillas including the Chinese and Vietnamese Communists, during the conflict phase at least, do tend to be fairly democratic because of how they operate. The members aren’t kept under tight observation by a religious leader, or all living in the same place. They have to operate on their own and be able to trust each other.

Plus, as Brett points out, they’re going to be taking high casualties. Not in big pitched battles with officers ordering them forward, but in constant small skirmishes and attrition. People generally are not in favour of dying, so guerrillas have to be reasonably motivated.

(And again yes there is coercion and other unpleasant stuff going on as well. But Mao wrote about establishing parallel justice systems and whatnot for a reason.)

One could argue that the Chinese Communists won because they were the last ones standing, but I really doubt that the Vietnamese could have sustained their campaigns against French and then US backed regimes unless they had a non-religious ideological framework for which a significant percentage of people willingly risked their lives.

It depends on what you mean when you use the term “religion”. Try to define religion in a way that includes Theravada Buddhism, but excludes Marxism-Leninism

Do the majority of those who follow the ideology think that it comes from divine / otherworldly / supernatural beings? Do the majority think that there is some benefit to them personally after death?

Or even simpler, ask the followers of X if they think X is a religion. Very few communists or marxists will say yes.

Yes, this is a pedantic blog. I’m not trying to define exactly what a religion is, I think it is most accurate to say that marxism and communism (or for that matter capitalism, environmentalism) are not religions.

according to your definition, Theravada Buddhism does not fulfill this condition. Buddha is not considered divine, otherwordly or supernatural. Problem is, that we simply DO NOT HAVE transcultural definition of religion.

foxitt, the Buddha themselves don’t have to be considered divine, otherworldly, or supernatural, though given Buddhist cosmology (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhist_cosmology) I would argue that the Buddha probably is actually otherwordly, or at least could choose to be otherwordly if they so wished, which is pragmatically identical. Ideology is not identical to religion, even if they are related concepts.

I used the term quasi-religious because the communists obviously reject the idea of a deity but they are a transcendental ideology which people will sacrifice their own well being and lives to advance. There are other commonalities between that ideology and a more traditional religion.

As to the other point. The movements discussed may have a degree of democracy internally but they are also self selected and explicitly rejected abiding a democratic result from their larger country’s. They thought they knew best and were willing to use force to impose their vision on a majority.

The Chinese communists were rejecting the democratic result from who exactly? The Japanese who had invaded and occupied parts of China were technically representing a democratic government, but Japanese elections, not Chinese.

Not saying that Communist China was democratic, but the insurgency phase was … more democratic … than the alternative. Same for the Nationalists, they weren’t ideal democrats either, but more so than the Japanese.

Same for the Vietnamese, were they supposed to accept the election results in France that caused Indochina to be colonised?

As Brett points out, protracted wars are more about politics and people than material and firepower. Insurgencies without some degree of popular support don’t win.

There’s no clear cut obvious definition of what a democracy is to begin with. (Trying asking different people whether the USA is a democracy or not.) So if you have a particular definition of a democratic movement and/or quasi religion, then yes very likely there has never ever been a protracted war that was won by a democratic movement that wasn’t following a religious / quasi-religious ideology.

The US is not a democracy. It is a representative republic. Our Founders were not fans of democracy. Rightly as in it’s pure form it is tyranny by the majority.

It is a democracy in the modern sense of the word. If you use the concepts of the classical world, then all western democracies are representative republics (some with an added actor on top who cosplays a monarch).

Get the foreigners out! Tends to be a very passionate causus belli.

Roxana

March 7, 2022 at 10:01 am

The modern form of what the founding fathers refused is named ochlocracy, mob rule

OTOH they were comfortable enough with slavery

Thor, actually many of the founders were very uncomfortable with slavery. The issue was kicked down the road with results we all know.

It’s also worth noting that slavery was an ancient institution that had been accepted the world over for millenia and was only beginning to be questioned in the 18th c.

@Roxana

Maybe, but my point was

the so called founding fathers

were not an infallible eternal authority

as they are revered by many american right

That would hardly make them wrong about what form of government they made.

Roxana and Mary seem to overlook that the US constitution has been extensively revised since it was first promulgated. Whatever the founders envisaged, the US is now a (half-arsed) compromise between democracy and local oligarchy.

Given the ideological and, in your words, quasi-religious nature of national-identity, many countries in the world today already have pre-existing beliefs that could potentially buttress an insurgency.

Many people don’t seem to believe that national identity is an ideology, but it most certainly is, and quite a potent one as well.

Quasi-religions with their own martyrdom cults, in fact.

There can hardly be a city, town, village or hamlet in Europe or North America without its own shrine to its war dead, with annual rituals to pay thanks to the dead.

I feel quite sure Ukraine has the same, with new names to be inscribed on them after this war.

Germany is then not part of europe.

We remember our war dead and other, we do not thank them

Fair point. What about the Napoleonic Wars?

I´ve heard Blucher, Gneisenau and Clausewitz Barracks cited as proof that the army is Nazi and they were NS Generals.

Arndt is critiiciced for his antisemitism and thats it,

Thanking the war dead is hardly an important aspect of national-identitism*. The most important part is identifying ones-self as part of the national whole.

Not everyone does. One of my best friends calls himself anationalist and does not identify on any level with any of the countries he has lived with. But the vast, vast majority of people do, to the point where most of us will never even meet an anationalist.

*The ideology is so engrained that we no longer even have a proper word to describe it. Nationalism has gone from a word describing national-identitism to excessive patriotism.

Sergei

March 8, 2022 at 5:19 am

Nationalism is a border case

my country if right or wrong i do not care

is the wrong kind

Legitim Patriotism is

if right keep it right if wrong set it right

if need be with force

There are tons of soldiers’ memorials in Germany. In fact, there were two(!) at my old school alone. Many villages have small shrines or statues dedicated to the fallen. In Germany the cult is different to the US, I agree, but it still exists. I think in case of foreign invasion nationalism would see a big spike.

Chickpea

March 8, 2022 at 1:19 pm

There are tons of soldiers’ memorials in Germany

Yes there are from the liberation to the unification wars to WWI but the mindset has changed

To ThorDan:

I did not talk about nationalism or patriotism. Those are both ideologies, but I was not talking about them.

I was talking about nation identity. If you call yourself an American, or a German, or an Indian, you have bought into the ideology of national identity regardless of whether you also ascribe to nationalism or patriotism or not. One does not need to have a national identity, and I have met several people who do not have one and do not want one.

This ideology has become so widespread that many have seemingly forgotten that it is an ideology. Heck, it has become so engrained that we do not even have a word for the anationalists who reject national identity.

Scottish war of independence against Edward I and II? See the declaration of Arbroath.

The Indonesian Revolution of 1945-1949 probably fits the bill. At least the new republic _aspired_ to be a democracy — while at the same time the military commanders (especially Nasution) understood that the struggle for independence was inevitably going to extract a heavy toll in Indonesian blood.

The American War of Independence comes close. There was no ‘quasi-religious’ ideological framework, just “independence from Britain.” (Talk about democracy etc from an ideological standpoint happened after the war- although the colonies were already pretty democratic, with elected state legislatures and an indirectly-elected Continental Congress.) Certainly there was no call to overturn existing social and political structures: they simply elected state governors to replace the royal ones and continued with business as usual. Nor were any of them the sort of “tyrannical oligarchy” with the power or will to feed lives into a meatgrinder like Mao or Giap.

Washington essentially fought a protracted war against a much stronger adversary and won with crucial foreign support. In the Civil War, Lee insisted on fighting a conventional war against the larger, more populous and much more industrial North, and lost.

That wasn’t a “Lee” thing–nearly everyone in the Confederacy thought that way, partially because they knew good and well that a protracted war would end up wrecking the reason they seceded in the first place–slavery.

Well yes. But guerilla war is not an option when 40% of your population will join the enemy as soon as possible, and another 10-20% are opposed to you politically. Sustained guerilla warfare needs strong popular backing – whether that’s for the ideological cause or the prospective material rewards or rooted belief or some combination.

Tyrannical oligarchy is imo a pretty good way to describe the early United States. It was a society in which a very substantial part of the population had no legal rights at all, and another large part was expressis verbis disadvantaged by property requirements for voting. The whole war of independence was very much an upper class war. Fishermen from Rhode Island or a small Georgian farmer weren’t really the ones in conflict with British interests. Large landholders and merchants were. These people certainly had the power to – and did – feed civilians into a war which at first looked pretty unwinnable. Washington and the like certainly had a lot of power over the masses by design of their society.

I really don’t see how the early US were any more liberal to the vast majority of the population, not the landholders, than the Vietnamese or Chinese rebels were.

That is certainly an interpretation of history, yes. The fact that a higher proportion of the people in the early United States could actually express their opinions via voting than anywhere else in the world at the time, is, of course, completely irrelevant.

If half of the population of the country can vote, and the other half are slaves, is that country more liberal than a country in which only a quarter of the population can vote but no one is enslaved?

The men who threw the tea into the harbor, or who gathered on the Lexington green, were not large landholders. A rabble in arms, as some have said, or more neutrally, small freehold farmers.

Re: “The Ukrainian army thus cannot retreat forever into functionally impassable terrain”

Western Ukraine has the Carpathian Mts where Hungary has territory on the western side. To the north along the Belarus is what used to be swamps. I watch supplies being flown into Rzeszow in south eastern Poland. Rzeszow is about 100 miles from Lviv. If there is any place in Ukraine fit for protracted resistance this is the place. With EU and American industrial, logistic, surveillance and military power this place can be defended forever.

Brett,

I think you’ve made a problematic assumption here. You are assuming a unitary state. Perhaps like Vietnam where everyone is Vietnamese. Or for that matter everyone believes in one China.

Ukraine is not at all like this. Roughly speaking you can look at the Ukraine as being divided into three, more or less, coherent groups. There is a Western Ukraine, Ukrainian speaking which was part of the Austria-Hungary Empire and which is Catholic, the core or central part of Ukraine which tends to be predominantly Ukrainian speaking speaking and Orthodox and Novorossiya in the southeast which is predominantly Russian-speaking, culturally Russian, and Orthodox. We will ignore the other multitudinous small groups that are kicking around. Oh, almost forgot, you have to remember that many in Novorossiya (Donetsk and Lugansk) will have close family ties in Russia including down to siblings.

Much of problem coming from the 2014 Maidan coup comes from the fact that the people in South East Ukraine, Donetsk & Lugansk oblasts were not impressed that their candidate, the legitimately elected President Viktor Yanukovych, corrupt as any other Ukrainian politician but still legitimate, had been turfed out and replace a candidate heavily supported by Western Russian Ukrainian groups and the USA.

This was rapidly made worse by the fact that the new Kiev government which was highly “nationalistic” immediately banned the use of Russian as an official language including in education. I’m from Canada. The language issue is a wild red flag to me. I was not at all surprised to discover Donetsk and Lugansk had declared independence even though it appears the Kiev government repealed the law almost immediately. In fact, as a Canadian, the outcome was obvious.

In any case the new government’s actions led to a declaration of independence by the 2 oblasts, giving us the Donetsk People’s Republic & Lugansk People’s Republic who have, for the last 8 years, have been fighting off official Ukrainian and semi-unofficial Nazi forces. Currently the casualty count seems to be about 13,000 dead, mainly civilians. There is not a lot of loyalty to Kiev here.

I really don’t know but I assume there’s are fair number of people in the central area of Ukraine who are heavily sympathetic to the Donbas republics because, if nothing else there are a lot of Russian speakers there, probably a lot of whom have family in the Donbas republics. They’re just as likely to support a Russian invasion as they are to support Kiev particularly as the atrocities by the Azov Battalion seem to be growing.

When one comes right down to it, I can see that the South Eastern part of Ukraine, clamouring to become the new Republic of Novarasiya just might bugger up Ukraine’s protracted war approach. It is kind of hard to hold a protracted war when nobody wants to play. Or they’re playing on the other side.

I think you are understimating the diversity of both China and Vietnam, both of which had (and still have) some pretty big internal divisions, (and trying to curry favour with a minority group that opposes the guerilla movement is a true and tested strategy, which sometimes works and sometimes doesen’t)

You are right. I was vastly over-simplifying but part of what I was trying to do was point out that in the Ukraine we have a situation where it is not clear that all the components even agree that they want the “invader” gone as much as they want independence from the country as it currently operates, i.e. the Donbas Republics.

I was making the assumption that pretty well everyone in China wanted the Japanese out.

You could likewise make the point that not all Ukrainians in the Russia-occupied irredentist regions want to leave the Ukraine. The support for “independence” (or rather, secession) is not nearly as uniform as you seem to be assuming.

Polling indicates that a huge majority (close to 80%) of Russian-speaking Ukrainians do not support a Russian aggression. In the South and Central regions, opposition was over 90%. Not all speakers of Russian language drink the Kool-Aid of esoteric ethnonationalism, and people’s neighbors and relatives getting indiscriminately slaughtered by the aggressor will further dampen potential Russian support.

Pretty well everyone in China did want the Japanese out. How they felt about the PRoC vs. RoC fight is a completely different matter. Brett didn’t assume a unitary state. He explicitly mentions the notion of convincing people your side is better than the other side. That implies that people could be thinking that the other side is an option.

And we have some idea of how the different regions of Ukraine felt about being part of Russia before the war. For example, a small majority of the people of Crimea were in favour of becoming part of Russia before that region was annexed. (Which supposedly became 97% shortly after it was annexed.) The two south-eastern regions which are the Russians’ excuse for this war have not had a majority in favour of leaving Ukraine at any point in the last 8 years.

The opinions of the people of Ukraine now are going to be heavily influenced by what they hear of the war. Whether that is the biased news reports coming from one side or the other, or the real-life experience of a war that was forced upon them (whether they call that aggressive invaders for foolish defenders). And as Brett said, at the moment the Ukrainians appear to be winning the information war.

> For example, a small majority of the people of Crimea were in favour of becoming part of Russia before that region was annexed.

IIRC this was according to a referendum organized by pro-Russian groups which had the options “become independent” and “become member of Russia” but not “stay in Ukraine” and afterwards many people said they would have voted for the third if that had been an options

Groups who were not in favour of leaving Ukraine were encouraged not to vote.

Even then the majority was only achieved with the russian rented territory

Vietnam was not a unitary state at the time, and there existed significant religious and ethnic divisions within the country.

I would note that if the Eastern part of Ukraine is somehow heavily populated by people who maybe want Russia to invade, then Russia’s apparent policy of shelling those cities and evacuation routes is not the way to confirm their support for your occupation.

I am also Canadian, and while we certainly have an abundance of historical divisions and ongoing grievances with each other, I have little doubt those would be set aside quite quickly in the event of a Russian invasion.

> the Donetsk People’s Republic & Lugansk People’s Republic who have, for the last 8 years, have been fighting off official Ukrainian and semi-unofficial Nazi forces.

This quote is basically how to spot a Russian troll. Russian propaganda promotes a very simple view. There are two types of people:

1) Russians, who fought the Great Patriotic War,

2) Everyone who disagrees with them is a Nazi.

Russians couldn’t even pass for an European if they wanted. It requires a basic familiarity with how Europeans think, and in this post, there is none. All Russians follow the same template. The war must have started in 1941, because otherwise they’d have to admit Soviet Russia conducted a war on the same side as Nazi Germany.

By the way, according to statistics, Russians increasingly don’t perceive themselves as Europeans, and increasingly approve of Stalin. This is not some die-hard tankies – the trend is strongest among the youngest.

…The Azov Battalion are legitimately a neo-Nazi-esque Ukrainian nationalist group which was indeed made a semi-unofficial part of Ukraine’s armed forces in the area, in large part as a response to Russia’s support of and therefore the extended period of insurgency in eastern Ukraine. They were basically an evil Ukraine felt was necessary because they could at least count on the hypernationalists to be opposed to Russia there. Like, they seem to be trying to promulgate the idea that the Donbas regions have legitimately seceded when they haven’t and there’s good reason to believe any elections that would have supported such an outcome were not free and fair, so that might be troll-ish stuff, but the neo-nazi paramilitary shit is 100% true.

And frankly, if you’ve got Nazis around, may as well make them go fight your protracted war so they get killed off, rather than leave them to gather weapons and strength and try for a coup later.

> This was rapidly made worse by the fact that the new Kiev government which was highly “nationalistic” immediately banned the use of Russian as an official language including in education.

Truth is literally the opposite of what you’re saying. Here are two army recruitment videos. The first is Ukrainian from 2014, the second – Russian, from 2017.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NOCbW1hc6Ng

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aqek78JXckw

The Ukrainian video “Each of Us” shows a sequence of individuals introducing themselves. “I the only son. I’m a fan of Shahtar Doneck. I’m a geologist. I’m the neighbor who bangs on your radiator.” and concludes with: “Neither of us was born for war, but we’re all here to defend our freedom”.

The Russian video goes like this: “This is the first day of your new life. No one cares who you were before.(…)Each day makes us stronger. Scars are everyday life.(…)You are the main enemy, the yesterday you.(…) Your task is to find the enemy, get him, be better than him and return as a victor.(…)”

The contrast couldn’t be any bigger. The Ukrainian video is an affirmation of individuality, of humanity. It rejects the old system, ‘homo sovieticus’. It uses Russian language(so much for banning Russian!) and even English subtitles to make it accessible to a wider audience. It’s the opposite of nationalism.

The Russian video is pure testosterone, hate(including self-hate), fanaticism. They want to transform people into cold Russian killing machines.(no subtitles)

.

The main reason why Mao won however was that he received massive support from the USSR, while Nationalists ended up being left to dry by the West – in fact, US at the time was more friendly to Mao than to Chang Kai Shek. So the main conclusion is that foreign support is absolutely crucial.

Ironically, Stalin was arguably more friendly with Chiang than wiht Mao, he kept trying to get Mao to accept a subordinate position in a unified government, which of course neither of the chinese leaders were willing to countenance.

Ironically the largest bit of help the US provided to Chiang, airlifting his elite divisions into Manchuria, was also the greatest boon to Mao, since they ended up being cut off and he could seize their equipment.

This is simply not true at all. Chiang received massive, eye-popping sums of money and mountains of equipment and support from the west, primarily from the US. The notion that he was left out to dry was pushed by the China Lobby at the time to distract from their own incompetence at Mao whipping their ass, and was used as a convenient cudgel against Truman by red-baiters.

Correct. Stalin kept pushing for Mao to compromise, because he didn’t think he could win outright, but much as in the Russian Civil War, the US war in Afghanistan, etc, no amount of foreign aid will suffice to overcome massive corruption, incompetence, and lack of motivation.

If corruption, incompetence, and lack of motivation doom a military effort, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is truly and thoroughly doomed.

Ehh. I’m less optimistic. While Putin’s Russia has all of those factors, I’ve yet to see indication that they have them to the degree that Chiang’s KMT did.

With the power of future knowledge, I think there is now a solid future indication.

Hey Bret,

I would love to see a post about war propaganda.

Please watch John Pilger’s ‘The War You Don’t See’ (2011), which is a powerful investigation into the media’s role in war, tracing the history of ’embedded’ and independent reporting from the World War One to the destruction of Hiroshima, and from the invasion of Vietnam to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

You can find it in vimeo!

thank you, from ukraine with love.

Looks prescient so far.

One wonders if defense budgets should have fewer jets and more money for will– not just hearts and minds abroad, but at home.

But then, as a US American, I’m rather glad that they do not.