This is the back half of the second part of a four part series (I, IIa, IIb, III, IV) examining the historical assumptions behind the popular medieval grand strategy game Crusader Kings III, made by Paradox Interactive. Last time we looked at how the game tried to mechanically simulate the internal structure of the highly fragmented polities of Christian Europe from the ninth to the fifteenth centuries. While that model has some necessary simplifications (both in flattening noble ‘ranks’ to a single system and in avoiding vassals with multiple lieges), on the whole it is a very capable simulation of vassalage-based decentralized polities, given the constraints of game design.

This week we’re going to take the same question and turn both East and South to the medieval Islamic world. I sometimes find that students often assume that while medieval Europe was fragmented and decentralized that the Islamic world must have been unified with stronger central governments.1 But as we’ll see from a political standpoint both halves of the broader Mediterranean world faced similar problems with fragmentation and decentralization, with similar results produced by somewhat different causes.

Consequently, while it is clear that the basic structure of vassalage that CKIII employs was designed first for the fragmented polities of Christendom, it isn’t necessarily a terrible fit for the Islamic world of the period either. That said, clearly some adjustments would need to be made, so this week we’re going to assess what adjustments CKIII makes to this system to reflect Muslim polities in this period and the degree to which they are successful.

It is worth a brief note on the way that the Crusader Kings series has developed, because while the systems for ‘feudal’ vassalage were largely an iteration on the existing model established by Crusader Kings II, CKIII‘s system for modeling Islamic polities differently – the ‘clan’ government type’ – essentially jettisons most of CKII‘s systems and starts over. Crucially, Islamic polities were simply not playable in CKII on release, with the option to play them only being added with the Sword of Islam expansion, which also introduced their mechanics. In particular, CKII gave most Muslim rulers a unique government form (‘Iqta’) which enabled rulers to hold both castle and temple holdings directly (this is kept) and also had a higher default tax rate (this is modified heavily). Fragmentation was then encouraged through the decadence system, which offered large modifiers to levy morale and demesne income based on the ‘decadence’ of a ruling family, which was largely determined by the number of unlanded members of the dynasty. The idea of this system, one supposes, was that a polity would expand with very low decadence (because dynasty members would be easy to put on newly conquered holdings), but with a polygamous marriage system this would produce explosively large later generations as expansion slowed, causing decadence to rise to weaken and then fracture the kingdom. The system frankly never quite worked and doesn’t seem to me to have been well-regarded, so it isn’t surprising that CKIII largely starts over from scratch. Of course the other major design difference we must note here is that Islamic characters were playable in CKIII at launch, which is already a huge improvement at embracing the diversity of medieval Afro-Eurasia.

But first, as always, if you want to contribute to my decadence, you can do so via Patreon. And if you want updates whenever a new post appears, you can click below for email updates or follow me on twitter (@BretDevereaux) where I issue royal pronouncements.

In either case though, I need to engineer some pretty specific outcomes to enable the ‘detente’ struggle solution: I need to control less than half of the counties in Spain AND be allied with all of the independent rulers. So I’ve engineered the fragmentation here to create two new kingdoms in the north – Castalla and Navarra – which put me just under that percentage while keeping the number of independent rulers low (five total) so that getting the requisite alliances is fairly straight forward.

A Different Path to Fragmentation

I would argue that political fragmentation is one of the defining features of the Middle Ages in the broader Mediterranean (which is to say ‘of the Middle Ages,’ since I don’t think this chronological signifier has a lot of usefulness beyond that region), but not all political fragmentation is the same. The medieval Islamic world fragmented politically in this period just like post-Carolingian Europe, to the degree that by the time of the Crusades (1095-1291) the political structures on both sides of those conflicts were broadly recognizable to each other, but that process which produced that fragmentation was quite different and it produced different government structures.2

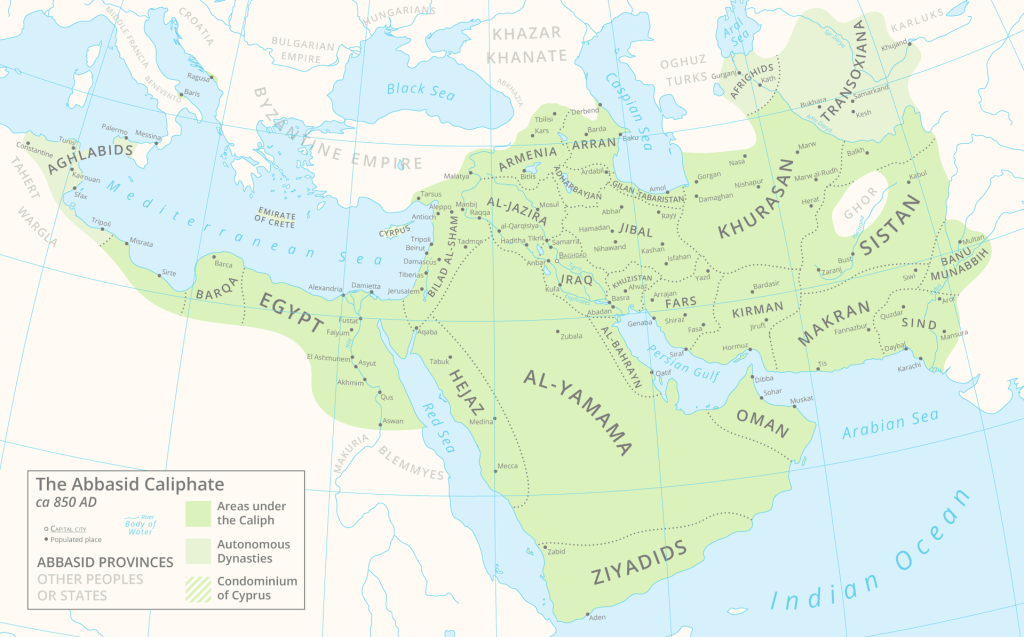

Now the game itself begins in 867, by which point the Abbasid Caliphate – itself a product of this fragmentation, having been the largest splinter of the Umayyad Caliphate’s breakdown – was already beginning to fragment itself, but to understand the process that produced this fragmentation, we ought to back up a bit further and start with the initial large Islamic polity, the Rashidun Caliphate (632-661). Now as you will recall from last week, one of the major problems that led to political fragmentation in Europe was that the highly centralized Roman bureaucracy simply did not survive into the Middle Ages and the educated bureaucrats did not exist to reconstruct it, forcing the polities that followed to ‘make do’ without a strong central bureaucracy.

This is not the case in the East. In a sense, the early Caliphs were facing a similar problem to the one the Carolingians had: having effected a grand conquest how to both militarily hold on to those lands and then also administer them. However, there was a key difference: whereas the Carolingians had overrun other small fragmented polities with limited administrative apparatuses, the initial expansion of the Rashidun Caliphate instead involved overrunning the eastern chunk of the still-extant and functional Eastern Roman Empire and absorbing entirely its great rival, the Sassanid Empire. Both states – and here I get to use that word! – were centrally administered by a capable and developed bureaucracy, a necessary product of their long conflicts against each other. Thus Abu-Bakr and later Rashidun Caliphs found themselves with a ready-made administrative system, complete with bureaucrats, that they could just repurpose to collect revenues, which is precisely what they did.

In order to hold the territory, they established a series of ‘garrison cities’ – permanently settled military forces; essentially armed communities of Muslims acting as the nails which provided the force to secure Caliphal political authority. However, Islamic armies are mostly not coming from an agrarian context so the normal expedient of military-settlers (giving each soldier a plot of land to farm in peace time) isn’t available because these fellows aren’t farmers. Islam already had a religiously encoded system for revenue collection in a series of religious rules for collecting taxes, a land tax (the kharaj) and head tax (the jizya) for non-Muslims and the provision of alms (zakat) for Muslims, with the latter being formalized as a state tax by the first Caliph, Abu Bakr. Because the Sassanid and Byzantine administrative bureaucracies for tax collection already existed, they could simply be put to work collecting taxes on this new regime (not actually so different from the old one), providing a steady and indeed comparatively massive stream of revenues to the state. Which then leaves the problem of our non-farmer military settlers.

The solution was the diwan-system. The word diwan comes from an Old Persian word meaning a formal state list or ledger, though it eventually came to mean ‘government department’ or the official who ran such a department. The very first diwan so established was the diwan al-jund created by the Caliph Umar in 641, as a list of Muslim warriors whose participation in the conquests entitled them (and eventually their heirs) to the payment of a salary (ata) and a food ration (rizq). It also functioned as a muster roll, so you both knew who you had to pay in peacetime and who could be called up in war. However, as Patricia Crone puts it, “it was not so much an institution for the maintenance of armies as one for the maintenance of Muslims.”3 The payments are thus untethered to any actual military service. They also seem to eat basically all of the revenues that the tax system is generating, leaving only a relatively small amount to float up to the Caliph.4

The problem is how this dovetails with the consensus-based model of political decision-making. These garrison communities naturally had their own leaders, whose support the Caliph could not effectively compel (because they subsist off of local revenues, not state revenues), with an intermediate layer of provincial governors generally chosen from among the Caliph’s close relatives, especially as we move from the Rashidun Caliphs to the Umayyads. However these governors both lacked the hard-edged tools to coerce these Muslim communities (who again, are still largely ruling over a yet larger non-Muslim population) because they lacked military force separate from them, but they also lacked a cultural script (like a tradition of conscription into a citizen militia, for instance) which would enable them to compel these fellows to fight if they didn’t want to.

Consequently we see a series of power struggles where a given dynasty has firm control only over the garrison communities close to its capital and tries – often in vain – to use that military base to maintain control over the rest of the empire. The far-flung garrison communities then in turn react negatively to any move away from what they see as the ancestral and appropriate consensus mode of government, though of course for such a massive empire consensus-systems were hardly going to work either. The Umayyads, with their base in Syria try it first, holding together for less than a hundred years (661-750), before losing to the Abbasids, whose base was in Mesopotamia, which proved equally unable to hold all of the other Muslim garrison-communities by force of arms. The Abbasids fairly quickly lose control over Spain (756), Morocco (788), North Africa and Sicily (800) and then the greater Iranian region (c. 870) and Egypt (969), as the Muslim communities (and their leaders) in each region exerted their independence. The fundamental problem was that no region had enough of a concentration of military force to hold the rest by pure force, but the system and cultural script available did not have another mode of legitimacy which was functional at this scale.

The Abbasid response to this problem was to look for military force outside the traditional diwan-system. The ‘solution’ arrived at were the Mamluks, slave soldiers drawn predominately from Turkic-language speakers from the western Eurasian Steppe which conveniently bordered the Abbasid Caliphate on its northern side. Warfare on the Steppe tended to ‘throw off‘ significant numbers of captured slaves who, as steppe nomads, were already capable fighters and Abbasids could also already draw on Arab cultural traditions whereby clan elites might maintain a personal retinue of enslaved soldier-bodyguards. It was thus a fairly direct matter to use the vast wealth of their empire to expand that bodyguard into a serious military force to support central authority. And these fellows were very good at fighting; steppe nomads made the most effective horse archers anywhere in the world, a system of fighting that the Arabs also used (and so were familiar with) and which was extremely effective. And, being cultural outsiders who were never working within the Arab model of consensus government, Mamluks could be used to ‘police’ the garrison communities.

The problem, of course, is that establishing an ethnically distinct enslaved soldier class is politically unstable, leading to further fragmentation and military weakness. The first effort at creating a significant Mamluk slave-soldier corps was under the Caliph al-Mu’tasim (833-842); the first Mamluk revolt (a coup, really) occurred in 861, just 19 years after his death. That said, the resources for this system and the cultural script for its implementation were available in many places in the Islamic world and so the system was repeatedly implemented and then repeatedly exploded in the same predictable way. Successful Mamluk revolts ensued in Afghanistan (the Ghaznavids, 977-1186), and central Asia more broadly (the Khwarazmian Shah, 1077-1231) and in India (the Delhi Mamluks, 1206-1290) and in Egypt (the Mamluk Sultinate, 1250-1517). On top of which was the incursion in much of the Middle East of the Turks themselves (initially the Seljuks), which was in turn partly enabled by the fact that – perhaps unsurprisingly – Turkish Mamluks didn’t necessarily see the arrival of a Turkish invading force as something to be fought. The Turks then had the same fragmentation problem as the later Mongols would and one that should be immediately familiar to Crusader Kings players: partitive inheritance on the steppe model, leading directly to rapid political fragmentation through inheritance.

Patricia Crone sums up this process ably, I think:

In a sense the Abbasids were in the same boat as the Carolingians. Both were confronted with the task of creating polities for which their tribal past offered no models, but which could not simply be revised versions of the empires their ancestors had overrun, in the west because the fiscal and administrative machinery had collapsed…in the east because the desire was absent even though the machinery had survived. Both fell back on private ties, and in both cases the outcome was political fragmentation. But because the fiscal and administrative machinery survived in the east, the Abbasids could simply buy the retainers they needed, and so they lost their power not to lords and vassals but to freedmen.5

On the one hand the result here is fragmented and personalistic, much like situation in Western Europe and so the basic applicability of CKIII‘s systems seems good. On the other hand, these are systems that emerged out of different circumstances and while they both trended towards similar fragmentation, did so for somewhat different reasons and with different results.

Clan Governments

To represent this system, CKIII makes a few modifications to the systems we discussed last week. Islamic polities nearly always have the ‘clan’ government form. Clan vassals differ in two major respects from feudal vassals: first, their levy and revenue contribution is not fixed but varies based on opinion. This means that clan vassals with very low opinion might offer effectively nothing, but at very high opinion clan vassals can contribute substantially more than even the most extreme feudal contracts (which are very rare). The second major difference is that clan vassals suffer a relations penalty if they do not have an alliance with their liege (in addition to just being vassals). With just a few exceptions, alliances in CKIII generally require a close family tie by either blood or marriage, so this is essentially a way of saying that clan vassals which are unrelated to or distant relations from their liege suffer an opinion penalty and as a result supply fewer taxes or levies. Clan governments also get access to conquest casus belli, making it easier to wage aggressive war for territory both within their religious group and outside, though there is a piety/prestige cost.

There is another significant difference I do want to note briefly. We’ll get into how religion functions in the game next time, but I do want to note that most branches of Islam as represented in the game have the ‘Jizya’ tenet, which increases tax revenues for countries of a different faith than the holder, while increasing levy reinforcement rate for counties of the same faith as the holder. It also makes available a special vassal contract by the same name which does the same for a vassal (increases tax contribution, decreased levies). This can be a significant change in realm structure, particular in the 867 start where most major Islamic polities begin controlling sizeable regions which don’t share their religion (religion is modeled by the game on a county-by-county basis, so the game cannot generally simulate religious minorities within counties, although a number of events pointedly note their existence). In addition, nearly all of the branches of Islam as represented in the game have the ‘polygamous’ marriage type, which encourages (via penalties to piety) rulers to have multiple wives based on their rank.

Now there’s an important mechanical interaction here worth noting. As I’ve already noted (especially in the running commentary for my al-Yiliq game), partitive inheritance is a substantial factor in the player’s experience for much of the game. Apart from the Byzantines who start with it, pure primogeniture (eldest child gets everything, everyone else gets nothing) as a succession law cannot be acquired before 1200; ‘high partition’ which at least gives the eldest heir half of the holdings before splitting the rest between the rest cannot be acquired before 1050 (and in most cases not for a generation or two after that). Consequently rulers, especially highly ranked rulers who tend to have lots of sons are going to spend much of the game splitting their domain between all of those sons in each generation.

So Muslim clan rulers are likely to have many heirs, partitive inheritance and access to a fairly readily usable casus belli to seize territory. What that combines to produce is a situation where powerful or aggressive rulers expand aggressively, looking to accumulate enough territory to pass on to their multiple heirs to avoid fractionalizing their core demesne (and thus weakening the main heir). In the first generation, that produces a whole bunch of brothers who as close blood relatives can immediately conclude alliances with them, which is very handy if either one of them is the liege of the rest (because it removes that ‘clan vassal with no alliance penalty’) or if the family collectively are all vassals of the same non-related liege and are looking to form a powerful political bloc to potentially seize power.

But in successive generations things begin to unravel unless one has planned carefully. In the next generation down, what were brothers are now just cousins, which is not close enough to form an alliance without a marriage connection. Moreover, strategically, everyone is now looking for yet more conquests to find land for yet more heirs, so what was once a coherent power-bloc within he realm is now divided against itself. A diligent liege can hold it together with strategic marriages (having many sons also means having many daughters), but as the generations roll on and the kingdom expands those ties are going to get more and more distant, with successful ‘cadet’ branches increasingly becoming a threat to the main branch of the house holding the top-tier title. And because clan vassal opinion impacts levies and taxes, the swing in power is even more dramatic, from close relatives with opinion bonuses from close relations and interlocking alliances (who thus give more levies and money) to distant relatives without those bonuses and angry that there aren’t enough alliance-forming marriage to go around (who thus give less). Consequently realms tend to be coherent and powerful when expanding in their first few generations, but then even more than monogamous feudal realms, divide against themselves, fragment and weaken as expansion slows and clan-cohesion for the ruling house breaks down.

And this is one of those wonderful cases (as with Marc Bloch above) where I am almost certain I know what the developers were reading when they planned these mechanics, because this seems like a fairly direct effort to implement Abu Zayd ‘Abd ar-Rahman ibn Muhammad ibn Khaldun al-Hadrami’s – or just Ibn Khaldun as we generally refer to him – his theory of ‘asabiyyah‘ or clan cohesion, which we’ve touched on before. Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) was a Muslim medieval historian who wrote a world history up to his own time, with the focus on the Islamic world. Ibn Khaldun, in assessing while different polities repeatedly rose, fragmented and fell offered ‘asabiyyah as an explanatory concept. Initially, a tightly knit social group like a nomadic clan or tribe has very strong ‘asabiyyah as the tight bonds make the members more willing to fight for each other and more willing to cooperate and reach consensus. For such a group, force is less necessary to structure relations because of those tight clan ties.

That strong ‘asabiyyah in turn makes for strong military power, as the clan will be able to mobilize a high proportion of its members to fight hard and stick together. Other, less cohesive, groups will find their members absorbed into the strong ‘asabiyyah, allowing an ascendant clan or tribe to absorb its less cohesive neighbors and ‘snowball’ as it were. However as the group itself grows in both territory and wealth, the very clan ties that founded its strength weaken. Members meet each other less, have fewer interests in common and the polity is also incorporating conquered or absorbed peoples. As the ‘asabiyyah thus weakens, it becomes necessary for the polity – by this point we’re trending towards a state – to replace consensus decision-making with force to compel cooperation. But that’s much less effective than ‘asabiyyah-cohesion, leading to weakness and fragmentation. As that state fragments, it is in turn overtaken by groups – either within or without – with stronger ‘asabiyyah and the cycle repeats.

Now when I last discussed Ibn Khaldun, I noted that I thought his theory has useful explanatory power but only for a subset of states: weakly consolidated empires built by nomadic or semi-nomadic (or at least tribal) peoples on top of the agrarian foundations of more complex societies. Which makes sense, since for the six centuries prior to his life, that’s what had kept happening in Ibn Khaldun’s neck of the woods. Where Ibn Khaldun’s explanatory power struggles, I think, is his inability to imagine a nomadic people successfully managing the transition from ‘asabiyyah-based cohesion to a stable, long-lasting state based on royal or institutional legitimacy – a transition not from one form of power (clan cohesion) to a form of force (state coercion) but from one form of power to another form of power (state legitimacy). What he could not have known is that within a century after his death the Ottomans would successfully manage that transition; of course given how rare (but not unique) and remarkable an achievement that was, Ibn Khaldun can hardly be faulted for not foreseeing it.

Nevertheless, Ibn Khaldun’s model of ‘asabiyyah is obviously relevant for this period, since CKIII ends in January, 1453 with much of the Ottoman state-building project yet incomplete (a story, quite reasonably, for the state-focused EUIV). And it isn’t hard to see how the various mechanics of the clan system come together to try to produce something like Ibn Khaldun’s cycles of ‘asabiyyah: a house expands, forms a polity, remains very coherent and powerful for a few generations before fragmenting as the ever-more-distant ties undermine the strengths that elevated it. And at the same time, the mechanics – particularly the opinion-penalties to levies – mirror in a limited way the increasing difficulty of raising force in this system without strong consensus (represented by high opinion).

If anything I would say that the core interactions of this system stumble primarily by being too weak. The system set up by the Rashidun Caliphate effectively required active enthusiastic participation by its members, but in game an Islamic clan-type ruler can typically get away with begrudging acquiescence for surprisingly long, leading to a recurring problem where the major states of the Islamic world – especially the Abbasids – tend to be rather more durable and cohesive than they were historically (though in some ways this is typically matched by a Byzantine Empire which is often a lot more effective and powerful than it perhaps should be). If anything, the decline in support for unhappy vassals should be substantially stronger, with contributions running down to zero quite quickly at negative opinion (though I assume this was probably tried and abandoned because it had knock-on gameplay effects that were undesirable). As it stands now, there are enough positive opinion modifiers available to generally keep clan vassal opinion high enough to avoid the sort of internal decay that Ibn Khaldun was describing.

The other element that seems to me to be clearly missing here is the Abbasid resort to military slaves. Mamluks would be difficult to model in game because they are a power-center that cannot really be represented as a landed constituency. But in practice rulers like the Abbasids should be able to resort to stocking the equivalent of greater and greater numbers of men-at-arms units (that is, professional full-time troops paid directly by the ruler), at the cost of creating a political constituency in them which could revolt and seize power if given the opportunity. Something like a landless vassal mercenary company which could be progressively expanded to replace plummeting levies as ‘asabiyyah fails, but which then becomes a dangerous vassal (or vassals) if it joins a faction might work. As it stands now, it seems odd this piece of the puzzle is missing and one hopes that perhaps a future DLC will try to reflect this pattern in the mechanics as well. Perhaps with a developed system for representing Mamluks, it might be possible to intensify the impacts of declining ‘asabiyyah without breaking the delicate balance of power in the Eastern Mediterranean.6

On the one hand, I hope that the major Muslim polities outside of Spain (which got treated in the Struggle for Iberia DLC) are going to get a fairly substantial mechanics-and-flavor passes in subsequent DLC to build on these mechanics. I’ve already mentioned Mamluks, but some mechanism to recognize the distinction between the appointed governors in the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates (generally relatives of the Caliph) and the actual local leaders of the garrison communities would be good as well, though it would require a system for handling count-and-baron tier indirect vassals revolting against the king or emperor because they hate their duke-tier appointed governor, which the game currently cannot do.7 But on the other hand, I think the basic structure here is actually quite good at capturing at least some of the historical dynamics that made and then fragmented these historical polities. At the very least the solutions reached here are far, far, far better than CKII‘s (that is, this game’s predecessor, for those who dislike counting numerals) ‘decadence‘ system, which was far less satisfactory.

Simulating Fragmentation

CKIII‘s approach, particularly the need to fashion the game around a standard set of mechanics that work similarly for everyone, has its limitations. One limitation we haven’t mentioned yet (but which looms quite large) is that while the game does not feature any states, these actual regions historically did and CKIII‘s systems struggle to model them, a point we’ll return to later. Nevertheless CKIII largely succeeds in providing a historically rooted simulation – albeit with major simplifications – of the pressures of fragmentation and even efforts at later centralization in the period.

Readers who are not deep into the historical gaming space may not realize just how rare this effort at reflecting political fragmentation is. Nearly all of the most popular games in this space feature absurdly unitary states. The Civilization games (and their -alikes, like Old World and Humankind) present not merely states but nation-states forming in pre-history (with a common culture, language and political structure) and proceeding without fragmentation to the present, a system where states are unitary before the invention of the state. Both Medieval: Total War and Medieval II: Total War feature fully unitary states where the player is in complete command of all of the levers of policy, as does Total War Saga: Thrones of Britannia. The same goes for Age of Empires and similar real-time strategy games (e.g. Rise of Nations). The Mount & Blade series does feature non-unitary states, with kingdoms divided into a ruling clan and vassal clans, but those clans never in-fight amongst each other and the system has only a single tier of vassals (so no vassals of vassals), meaning that the kingdom largely still goes to war together.

Instead, political fragmentation within a polity is a theme largely left to narrative-driven roleplaying games (e.g. Tyranny, which not nearly enough of you have played), where it is narrated, not simulated. Crusader Kings III‘s effort to actually try to simulate fragmented polities is thus already pretty unusual. And the task was clearly very hard! Fragmented political systems are all about ‘fuzzy’ distinctions, situations where ‘the rules’ may or may not apply, actors whose loyalties and relative position in the system are often in flux and devilishly hard to define. In short, these are systems that resist simulation in general and particularly resist being reduced to game systems that in the end – because of how computers work – must be reduced to clear numbers rather than fuzzy distinctions.

The next goal will be creating an Empire of Hispania which can then absorb vassal kings, but that demands holding a much higher percentage of the peninsula (sigh). Our buddy Ajannas II isn’t going to go warring like that, since he’s made friends with all of his potential opponents, so that task will be left to his son…

And despite the limitations of this effort, I think it is fair to say that as a simulation of internal political fragmentation (packed as a game that has to be fun at some point), Crusader Kings III succeeds and indeed succeeds remarkably so. Some of this is due to a careful selection of time period: by beginning in 867 and ending in 1453, CKIII avoids having to deal with periods defined by substantially greater degrees of centralized power in most areas of the map, which allows its systems to be very focused on fragmented polities (though it also means that the game’s systems fudge the history a bit more at the edges of these time periods, as the developers have admitted). But I think a lot of it is due to a commitment to try to simulate these political systems at a fairly high degree of granularity. Sure, not every minor castellan or member of a town council is simulated, but nearly every polity has at least a dozen, if not dozens, if not hundreds of competing power-centers represented by different kinds of vassals pursuing competing aims. Relatedly, I don’t think it is an accident that the CKIII modding scene is so active. For modders that want to simulate fragmented political systems, CKIII really is practically the only game in town.

At the same time, the simulation that is fairly clearly rooted not just in historical facts of who-ruled-what-when, but also historical understandings of the broader institutions and historical forces that shaped these fragmented polities, from Marc Bloch’s conception of feudalism as a social system to Ibn Khaldun’s theory of ‘asabiyyah. Honestly, what struck me most writing this is the surprise that the system works, although it has come to work through a fairly clear process of iteration: Sengoku (2011) seems to have been something of a test-bed for Crusader Kings II (2012) which was actively developed on for at least six years (it’s last expansion in 2018) before those lessons were then deployed for Crusader Kings III (2020). The iteration clearly worked because each game built on the model of the previous entry in useful ways.8

All of that said, I think we are still missing a crucial component of CKIII‘s core theory of political history. We have polities and we have rulers now, but we also have to discuss how CKIII views rulership, which is where we will turn next.

- As best I can tell this is a product of teachers attempting to compensate for older, orientalizing views which presented Islamic polities as uniformly ‘decadent,’ weak and backwards as compared to European polities and perhaps somewhat overcorrecting.

- I should note here that for many of the Arabic or Persian words I’m going to use here there are a range of transliterations into English, including a lot of variation in terms of diacritical marks. I don’t know either of those languages, but I have tried to at least observe common transliterations (albeit generally with minimal diacritical marks as these are difficult to do in the WordPress editor and often not used in transliteration in any event). My apologies in advance for any errors I have doubtlessly made due to my unfamiliarity with the languages.

- P. Crone, “The Early Islamic World” in K. Raaflaub and N. Rosenstein, War and Society in the Ancient and Mediterranean Worlds (1999), 313. Much of what follows here is adapted from Crone’s summary there.

- This was an element of CKII‘s design I actually thought was curious. We see pretty clear evidence of persistent revenue problems for the Umayyads and Abbasids over time and part of the problem is clearly that revenues get eaten up by local garrison communities before reaching the imperial ‘center’ in Damascus or Baghdad. That in turn leads to taxes which were initially only imposed on non-Muslims (a slowly shrinking tax base, as slowly, bit by bit over time more and more of those tax-payers convert), particular the kharaj land tax, being imposed on Muslims as well, with substantial resistance to this as well. Yet in CKII it is just a general feature of Islamic ‘Iqta’ government that the central government gets a higher proportion of tax revenues; this is a point on which, we will see, CKIII‘s clan-government system is an improvement.

- Crone, op. cit. 326.

- And that balance of power needs to work because players in a game called Crusader Kings expect something approaching the historical crusades to be possible, which means that there both needs to be a functioning Byzantine Empire through the High Middle Ages and that it also needs to be opposed by powerful Muslim polities to its East.

- Perhaps some kind of use of the popular revolt faction mechanics, whereby when discontent with indirect vassals becomes high enough it triggers a major revolt in those far-flung regions?

- Because yes, I actually played Sengoku (2011).

Just took a look at your link to the Decadence system. One of the traits it flags as increased risk of decadence is “Homosexual”. Unless there’s a very compelling reason why in the context of an Islamic culture this should be so, that’s going to draw a LOT of criticism.

Decadence is material excess and self-indulgence, yes? If someone is homosexual they’re less likely to have kids, and if your culture’s main way to redistribute wealth and break up polities is by your children inheriting your wealth a homosexual ruler is going to have less children and therefore their wealth is going to remain relatively concentrated. This means each generation is going to have more money than they need to sustain themselves (material excess) and will naturally spend it on themselves (self-indulgence).

No joke, “you’re not having kids so what are you doing with your life” is a real argument deployed against LGBT+ people in the real world right now. I have no problem seeing such an argument used against folks in the past, when inheritance and family lineage was much more important.

Adoption is a thing. And has been for quite some time. I don’t know how it interacted with inheritance laws in the time period in question, but still.

The game models a specific class within a larger society wherein ‘adoption’ as we know it is meaningless. Nearly all direct ‘parenting’ of characters in CK is done by non-related persons who are in fact completely abstracted out of the game. And in this class, bloodlines are tracked as obsessively as with racehorses, so having blood- nieblings is much more important to them than having legal guardianship over some child.

Oddly enough, this was a time of great fostering of children in Europe.

“Adoption is a thing” : not in Islam, it is explicitly forbidden by the Quran (i.e. more strongly than by hadith).

There are weaker forms of “raising orphans and foundlings”, but the child cannot be a legitimate heir.

I don’t know about the Islamic world, but adoption was not a thing among the noble houses of Christendom. Wardship and service in another’s household were things, but inheritance was based solely on blood (or possibly marriage).

Adoption is banned in Islam. At least for the purpose of passing one the same as your blooded son.

I would assume cultures where court eunuchs played important roles would have an answer against that argument at least for some people

Many cultures with court eunuchs had them precisely so they would not corrupt things in interest of their heirs.

My general impression, right or wrong, is that where royal/imperial marriages were concerned attraction between the wedded was optional provided heirs were produced. A number of homosexual rulers e.g. Edward II seem to have met their dynastic obligations regardless of their orientation.

True, although at least in England, homosexuality seems to have made rulers unpopular. Certainly it hurt Edward II, and James I, although Richard I and William III seem not to have suffered a penalty other than not having descendants as heirs.

I think with England it was a matter of “being gay doesn’t matter if he’s a functional king, but if he’s not it’s going to be something else we throw at him.”

There’s some pretty major questions on whether William III was actually homosexual, too. He was certainly *accused* of it in his time, but that was an era of Jacobites & Anglicans accusing the “wrong” king of every scandal imaginable, so it’s hard to sort out any kernels of truth from the rumors. Additionally, William III was rather more credibly accused of carrying on an affair with a female confidant – his wife Mary certainly seems to have believed it, for one. Which suggests he was perhaps bisexual if the rumors were accurate, but eh, see above.

Richard I’s alleged homosexuality is one of those historical “facts” which everybody knows but for which there is actually little evidence. A great deal has been made of the fact that he shared Philip Augustus’ bed; but that did not imply anything sexual at all in an age when beds were scarce and multiple occupancy common; it was noted because PA was showing him great honor. True, he had no legitimate children and no known bastards; but then, he may simply have been infertile.

Related to what SnowFire said, I remember a friend arguing that a lot of the case for William III being gay made by his political enemies was “he doesn’t have many mistresses, don’t you think this is a bit suspicious” and this was only treated as credible because of coming after the reigns of Charles II and James II

(Said friend also argued there’s more evidence for Mary II being bi than the allegations about her sister or her husband/cousin – but she didn’t have political enemies making an issue of it at the time)

@Michael Alan Hutson

The lack of reproduction itself isn’t the chief issue since they do fulfill their obligations as royals. Sodom had no issue having children.

Its the larger implications of their example. And what it entails in society. In Christian societies as per Romans 1 Public unrepentant Homosexuality is one of the signs of a society in perdition.

And widespread enough along with other sexual perversions will result in the society being nuked like Sodom was.

Male characters who were greedy, lustful, vain, etc. could gain a “decadent” trait that would massively increase their contribution to your dynasty’s decadence score. If they were outside your diplomatic range/didn’t like you, there was nothing you could do to stop your dynasty from becoming decadent.

The result? You were hit with a “decadence revolt” wherein a large, powerful band of rugged, pious Muslims from the hinterlands spawned out of nowhere and would attempt to conquer you.

Essentially, the decadence system simulated a cycle of soft, effete “civilized” rulers being punished by hardy nomads, who then go on to become decadent themselves and continue the cycle.

It was the Fremen Mirage every step of the way, and was super lame.

If you use the Spanish Muslim kingdoms as an example is that in fact happened with multiple muslims invaders from north Africa entering the peninsula and finding the local muslims decedent in their opinion taking control for themselves

In fairness, Muslim Spain did sometimes have problems with invasions from North Africa, but pitching this as “Fremen versus decadent cityfied folk” grossly oversimplifies things…

There are analogies to historical precedent but that doesn’t make it a good analogue. All models are wrong, some models are useful.

Well, as a mechanic, the idea of decadence was to produce the kind of expansion-and-collapse that ibn Khaldun attempted to explain via asabbiyah, so it should by default always be going up and the player has to try and keep it tamped down. So partially tying decadence to traits like “Homosexual” which are randomly present and can’t be affected by the player is something that helps keep decadence increasing constantly without active management. It’s just that the semiotics of that association are pretty eyebrow-raising! It’s another reason why the Decadence system was poorly thought-out, of course.

Well, according to Wikipedia: “Homosexual acts are forbidden in traditional Islamic jurisprudence and are liable to different punishments, including flogging, stoning, and the death penalty, depending on the situation and legal school”

Seems like it was disapproved of. (And presumably it reduced the number of heirs of the people who conducted homosexual acts instead of heterosexual ones.)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LGBT_in_Islam

And historically, homosexuality was an important feature of early Islamic courts, despite the religious prohibition. As far as I’ve understood, a very large portion of medieval Arabic romantic poetry is about boys. So, in the culture of the time homosexuality was transgressive, and also decadent.

In addition, because this was pederasty, not homosexuality between equals, having your son be the boy lover of a courtier was socially demeaning. (Unlike in Ancient Greece, where Socrates was commended for his self-restraint for not having sex with his student Alcibiades, whose manliness was not in questioned by contemporaries. Being a victim of a pederast was part of the normal life of a Greek upper class youth, and not demeaning.) We know, from recent history, that revolts against local warlords who took sons of respectable families as lovers have been an important part of the self-understanding and internal mythology of the Taliban.

So, while using “homosexuality” as a marker for decadence seems transgressive and stupid for us, it may not be that bad a modelling choice. However, using it in a game that is being played by youth who don’t have a deep understanding of medieval Arabic culture, sends an ill-advised message.

Good points! I haven’t studied this area in much detail, but it seems that there was much eroticism of male teenagers. Abu Nuwas, known for his poems about wine and boys, seems a lot like Martial the Epigrammatist (whom I am more familiar with)

I forgot to clarify this: I think it is very insightful of you to mention that this mechanic might project a wrong image to the average player of the game

In a further blow to modern sensibilities, the kind of homosexuality that was tolerated in some Islamic settings, and embraced in some parts of the ancient world, was exactly the “wrong” kind, involving adult males and teenage boys, rather than consenting adults. I suppose you could feel better about the game by imagining that it is the former, “bad” kind of homosexuality which constitutes decadence.

“sends an ill-advised message”–I’m not sure what the purpose of computer games is, but the purpose of studying history is to understand the past as it was, not as we wish it were. If the purpose of computer games is to teach history (which Bret often implies it is, though I have no opinion), then worries about “ill-advised messages” are misplaced.

This is going to depend a lot on how games are perceived and how the game was advertised, for instance our host talks about this here :

https://acoup.blog/2022/04/15/collections-expeditions-rome-and-the-perils-of-verisimilitude/

Paradox games aim to be fairly historical, including historical intolerance, though with default settings you can, with great difficulty, change matters and with the introduction of game rules you can turn it off.

Random aside; due to a weird quirk of mechanics it’s actually pretty difficult to not have the first Crusader State be run by a woman. Since you can only designate people who aren’t heir to any titles, you’re running partition, and your dynasty doesn’t yet have a lot of adult collateral cousins whose dad is a mono-count you’re usually looking at nominating a woman.

And that is how my latest game has the Empress of Outremer and Pope of the Outremer Christian matriarchy.

Decadence covers people’s perceptions and not necessarily anything innate to the character.

I kinda assumed that the Decadence trait is supposed to represent how decadent other people see Character X as, not how “innately decadent” they are. I mean, even the most hedonistic Mujahid (reverse crusader) will never become decadent.

Part of that is in an attempt to find the least objectionable interpretation of a mechanic that’s rooted in orientalist tropes however you look at it, so YMMV on whether that argument changes your opinion of the mechanic.

While orientalist tropes did and do exist, our pedantic host notes that the original source and almost certainly the basis for CK 3 is Ibn Khaldun. A Muslim medieval historian, writing about his own Islamic societies. That doesn’t mean he was automatically right, but ‘decadence’ was not just dreamed up by Victorian era English speakers.

I think there’s a difference, though.

Ibn Khaldun wasn’t saying that the clan lost power because they were all taking hashish and screwing harems, but because the clan members drifted apart and lost unity.

That’s the difference between the CKII and CKIII presentation.

I always took “homosexual” in CKII to mean *openly* homosexual. At least for “everybody kind of knows but nobody talks about it” levels of openness. Thoroughly closeted homosexuality would be inconsequential in game terms.

And, it does make sense that there would be a correlation between perceived “decadence” and a privately-gay character’s willingness to semi-openly embrace homosexuality at the expense of their traditional duty of matrimony and fatherhood.

CKIII treats it more like this. It’s a trait that a character has, but it’s not known by default and doesn’t affect opinion. It can be uncovered by other characters as a “secret”, though, and then either used for blackmail or exposed, which then triggers opinion penalties.

All this interacts with the religion system as well, with one of the options for a religion being the acceptance of homosexuality, which removes the opinion penalty for being homosexual as well as the treatment of homosexuality as a “secret” than can be uncovered.

There are also various levels of disapproval. From approved of (gives opinion bonus) over acceptance (no penalties) disliked (gets treated as a secret and gives opinion malus if known) to criminal (not only gives an opinion malus but also an imprisonment reason)

Decadence was heavily based on “things which are sinful in (fairly strict) Islam” even then, it was not a great match but that’s why it includes e.g. homosexuality.

True. But then again concessions will just end up watering down “Decadence” into meaninglessness.

So either Decadence exists or doesn’t exist.

These posts are always a great reason to look forward to Friday, and they always leave me eager for the next one!

I’m newly retired, and struggling with the “What day is it again?” problem. Knowing that ACOUP publishes on Friday seems to be the best counter I’ve got so far.

I wish there was some way we could get a narrated video playthrough of one of your CKIII games.

What with all your copious spare time of course.

I mean, I am sort of doing this in the captions to the al-Yiliqi playthrough pictures.

Minus the video. And in less detail than a Let’s Play would provide.

Not saying you should start a Paradox Let’s Play channel (it takes more effort than it looks like, especially if you keep a schedule), but a sprinkling of AAR over a historical blog post isn’t the same thing.

Love to see Tyranny mentioned – is there any chance it could be the topic of a post or two later down the road?

My take on Tyranny from having played it a few times is that the ethics and themes of it are an uncomfortable mish-mash of modern and ancient tropes. One of the earliest interactions is to look down on someone for looting a battlefield, for example, but this is a bronze-age setting with few professional, standing armies; looting enemy combatants has been a part of warfare all the way up to the point where what you were equipped with was routinely better than they had — and even then plenty of folks took trophies to show off at home! No one in the setting should blink at looting the dead, but since the modern world views it as a bad thing to do we’re given the opportunity to reprimand someone for it.

I haven’t gotten around to playing Tyranny yet, but from what I recall, letting a modern player apply their modern morality to a fantasy world with ancient morality is a feature, not a bug. Not everyone wants to be Naofumi.

(Naofumi, noun: Protagonist of the light novel/anime The Rising of the Shield Hero, best known for owning slaves, financially supporting slavers, verbally defending the institution of slavery, and existing within a narrative which does backflips to give him every justification imaginable to enslave people, up to and including having some of his slaves actively choose to be enslaved and acting like freeing them from slavery is a horrible thing to do. Also known for using shields…one of which gives his slaves an XP bonus.)

(…Look, Shield Hero fans. I know there are non-slavery-related things in this series, but slavery is the biggest elephant in the room, and the only one relevant to this metaphor.)

I think that contradiction is deliberate, given that A, your player character loots every battlefield they encounter because they are an RPG protagonist and B, the entire game is about the ways that your PC is an arbitrary, brutal hypocrite.

More generally, yes, it’s a mish-mash of a fictional setting where wars of conquest are considered normal and a real-world context where the player (hopefully) holds the modern view that war is bad. That’s a tension that exists in tons of games (including CK3), but nearly all of them sweep it under the rug by erasing or abstracting the violence to the point where the player doesn’t have to feel like they’re doing something wrong. What makes Tyranny interesting is that it quite purposely goes the opposite direction and tries to force the player to think about what they’re doing.

Heck, when I was watching Band of Brothers recently, I occasionally felt like the protagonist company looted their way across Europe. Not at the pillaging levels of earlier times, perhaps, but they were not at all subtle about taking anything they wanted which was not nailed down and could be characterized as having been previously owned by Nazis.

(This is less present in the subsequent series, The Pacific, and I can only guess that it was because so much of the fighting in that series was conducted on remote islands.)

Well, I’m happy to say that my ancestors looted their way across Georgia (and South Carolina). Those people deserved it, and we gave them what they deserved.

No offense, but isn’t that the justification given by most people for their horrible actions across history?

“They were evil and deserved to be pillaged/raped/burned”

And this is why precision – not just pedantry – is important. As an Australian I don’t know what you’re talking about. A quick bit of research turned up three possibilities:

1 European colonisers in the 17th C

2 Union army in the American Civil War

3 Klu Klux Klan post American Civil War

I would not be happy with two out of three.

Well, yes, the justice of doing something bad to someone depends on whether they do, in fact, deserve it. And happily, I was talking about item 2. In all cases, let history (and possibly eternity) judge.

At least you specified (and South Carolina), otherwise it would have been even more wildly non-specific ! XD

Given the antics the Indians of North America got up to, I’m okay with the first one. And the second.

IIRC, at least one of the reasoning is less about it being wrong to loot per se, but because *you’re taking what belongs to Kyros*.

I would also like to see a post on Tyranny.

One thing I found a bit strange about it was that the disposable grunts were equipped with bronze weapons, while iron weapons were reserved for the elite troops, when my understanding is that, irl, one of the big advantages of iron over bronze is that it’s a lot more common, and thus easier to equip a large army with. Of course, you could just say that copper and tin are more common than iron in Tyranny’s world, although that raises the question of what prompted the shift to iron in the first place. That probably wouldn’t be enough for a blog post on its own, but maybe as a lead-in to a post (or series) on the bronze age collapse, and what caused the shift from bronze to iron?

Iron is better than bronze in a lot of games; I figure that they figure newer = better.

Good steel is better than good bronze, but it’s harder to get to good steel than it is to get to good bronze.

Tyranny throws this for a loop, though, because iron working is a magical discipline. At one point you can watch an ironsmith at work and she literally shapes a helmet with her bare hands, reaching into a furnace hot enough to make iron malleable without any kind of protection. Iron is better in Tyranny because magic makes it better, not due to any part of metallurgy.

Bronze was a very mature technology, iron less so for a long time. You’ll recall references in the Old Testament to both bronze and iron; iron was originally the cheaper but crappier substitute for bronze.

That’s kind of my point. If iron is the cheaper, crappier, and newer alternative to bronze, then why are the elite and tradition-obsessed Disfavored using iron weapons?

It’s meteoric iron? It was prized enough to be used as jewelry.

Iron is an imperial monopoly in the game, and I guess the mage-smiths can make the good stuff. The Disfavored switched from bronze to iron when they swore allegiance to Kyros and getting the quantities of iron they do is apparently a sign of the Overlord’s favor.

I wasn’t aware of how these mechanics work and kinda assumed western European structures were just copied. Great post. I’m no thinking that an intrigue heavy strategy would be really effective against a large realm like the Seljuks or the Abbasids. ie, specializing in intrigue and assassinating popular skilled rulers so that disliked rulers lead to a less stable realm.

You’ve been hinting at a frustration with the game’s lack of “state structure” mechanics. I just did a game with the 1066 Normandy start and managed to restore the Roman Empire. It was a smashing success, but I really missed the CKII retinue system. I was swimming in gold and would have been able to invest in a transition to statehood if there were any mechanics to do so. What kind of mechanics would best model state structures in this period?

Assassinating good rulers so incompetent ones come to leadership is always an effective strategy, no matter the govt type in question.

The retinue system from CK2 is almost entirely replicated in the Man at Arms in CK3. If there any part of the retinue that you feel are missing. The only real difference is that retinues are always raised while the Men at Arms are not. You get the same ability to select troop types as well as variety based on culture and region.

CKIII has caps on men-at-arms designed specifically keep you from using them the way late-game human-played empires tended to use them in CKII.

For me at least, them always being raised was a good part of them feeling like a big shift.

With always having them raised, you could station them for quick response, or place them next to a place you want to conquer, declare war, then immediately move them in. With the current system, MaA are just levies but more effective in combat, they don’t alter how they’re used or how you play (except for siege weapons)

Excellent post! Thank you Bret!

Interesting that “enslaved person” is no longer important terminology when dealing with Mamelukes Seeing as you have made your position on this clear (i.e. using “slave” implies that slavery was more than forced to the enslaved persons nature), it seems that you believe that slavery in this instance was justified. Or did you forget? It seemed important enough to preach about before.

He’s never pretended to have any sort of consistency about terminology, and “preach about it” is just something you’ve invented, but it would be nice if he went through and edited this post to better reflect that enslavement is a (bad) thing that happens to humans. “Slave” was coined to describe the enslaved as being fundamentally different in type from other kinds of humans, and has been used extensively to argue that the enslaved were in some ways simply not human.

There’s no value in choosing to use “slave” over “enslaved,” but there can be malice.

Look, slavery was a commonplace in the Muslim world, and remained so well into the 20th century. It’s one of those historical facts which needs to be taken as read, and I see no point, aside from moral masturbation, in using “enslaved person” where the noun “slave” works perfectly well (no more than, say, “enserfed person” as opposed to “serf,” or “homosexual person” vice “homosexual.”)

No, those are all viable substitutions. It doesn’t cost you anything in terms of readers’ ability to comprehend your writing if you use them, so why not?

But there is cost. The entire point is to cost the reader’s attention and divert it to a specious theory having no relevance to the subject matter.

Terms such as “enslaved person” are longer, clunkier, and impose more cognitive load on your readers, all of which are costs.

Also, for what it’s worth, actual slaves or freedmen have historically been quite happy to use the word “slave” (or whatever the equivalent word was in their own language). “Enslaved persons” is a modern academic term, not a self-descriptor of the slaves themselves.

> impose more cognitive load on your readers

I think that’s the point.

At least for me, “enslaved person” conjures up a far more violent image than “slave”, which does indeed impose more cognitive load and makes the inherent immorality harder to shrug off.

However, that can’t be generalized. People who yammer of “enslaved person” are much less likely to support anything that would actually try to help people actually enslaved right now in China.

I think that’s the point.

But I hope you can at least see that some people might not like their reading material to be made deliberately harder to read so that the author can signal that he, like everyone else in the western world, is opposed to slavery, and that these people might consequently get a bit annoyed at terms such as “enslaved person”.

Especially when you know that it’s no reason to believe it, that the very person who insists that “slave” is tainted may be in Congress the next day arguing against laws to prevent the use of slave labor in making products.

Did you rush down here to plant your flag that OGH is actually a bad person and should be disregarded, or did you bother to read the entire article, first?

Quoting from the previous series on EUIV here:

“Quick note: I tend to prefer in nomenclature to say ‘enslaved persons’ rather than ‘slaves’ because I think the reminder that people in slavery were people held in bondage is valuable, especially in teaching contexts and I trying to retrain my brain to ensure that terminology by habit (I do not, by any means, claim to have achieved any great consistency on this point; this is not some holier-than-thou bit, just an effort to improve my teaching.)”

As someone so nearly said:

“Interesting that you always used to say the sky was blue whenever you mentioned it; but now you have mentioned the sky without reminding everyone that it is blue. It seems that today you think that the sky is red.”

Slavery is clearly not the focus of this post, or anything remotely resembling the focus. It is a brief, offhand mention in the discussion of a longer topic.

Please try to follow Wheaton’s Law here.

I was glad to be spared the prostration over common sense terms for once tbh

I’ve never played any deep historical simulation games like this, but the more I read about them the more I’m willing to give them a try. They all seem *really* complicated, though; where would be a good place to start, given that the closest I’ve ever come is playing Civ 5?

CK3 is relatively easier to understand for an outsider because a lot of the game mechanics are based on simulation the actions of people rather than inscrutable economic math

CKIII is maybe the easiest to learn of Paradox Grand Strategy games (except Stellaris, which is not historical). All the important information are clearly accessible, and it is fairly easy to understand what happen in the game.

A good point to start in my opinion is to start as a major vassal in a large kingdom (as Mathilda of Tuscany in the HRE for instance). It allows to understand how the systems works. You have few vassals to manage while being protected from external threats.

Being a vassal also gives you a clear objective : usurp the throne of your liege or become independant.

A small domain in CK3. CK3 does a lot more, compared to other games in the franchise, to make mechanics transparent and comprehensible. Starting in a small realm like Ireland means you can focus on a smaller number of characters to keep happy, giving you a better chance to learn the mechanics.

Ireland has been called Tutorial Island since the CK2 days. At typical CK2 (and both CK3) start dates, Ireland is dominated by independent rulers that only have one or maybe two counties—the perfect environment for learning the basic mechanics of Crusader Kings without having to juggle too many vassals, rivals, and vassals of rivals at the same time. And once you’ve crowned yourself High King of Ireland, you have an obvious next target—conquer or marry your way into Great Britain.

It’s also relatively isolated; the English, Scots, and Vikings might give you a bit of grief, but the French, Holy Romans, Actual Romans, Saracens, etc probably won’t bother you unless you go all Plantagenet and start taking bites out of the continent.

I’d suggest playing through the actual tutorial of CK3, which is set on Ireland as befits it’s tutorial island status, but which also gently introduces concepts and mechanics and gives a bit of guidance for the early steps when things can otherwise seem a bit overwhelming.

unlike the tutorials in earlier parts of the series it’s honestly a pretty good introduction IMO

There is a key difference between CK and pretty much every other strategy game that you should be warned about ahead of time: Civ et c. all teach you that you should be on an unbroken climb in terms of power as a player, but CK is designed around regularly de-powering you throughout the game; in a typical CK run you will encounter over a dozen points at which you are dealt a setback so large that it would lead to a restart in Civ.

I love civ games and turn based strategy in general, but I bounced hard off of EU4. This series inspired me to give CK3 a go and I’m having a blast.

With the caveat that a few dynasties seem to have come to the conclusion that succession crises were real bad and took extreme measures to prevent them. No rule is absolute, even for absolute rulers.

But landless (or landed-only-by-another-ruler’s-grant) entities composed primarily of armies did exist in CK2. Perhaps we’ll see Mamluks alongside holy orders, condottieri, and the like in a future DLC?

The nice thing about making more types of character playable in base CK3 is that it lets DLC focus on specific mechanics like that, instead of needing one DLC to add every Islam-related mechanic.

I think it would be possible to create a simulation that could approximate those fuzzy distinctions, if you added enough variables to the code. The real hurdle, I feel, isn’t that you need to simulate fuzzy human relationships on a system which can only understand numbers—it’s that you then need to explain those numbers to a human which doesn’t understand numbers nearly so well.

(Well, also development constraints, but those only kick in once you have a product someone might want to develop.)

When you say “holy orders”, I assume that you mean the military orders. The normal monastic orders of the Middle Ages were important, but even in Ireland, the individual monasteries were usually the political players with whom the local nobles allied. The Fransiscans did ally with the Emperor as an order for a while during the poverty controversy, but they didn’t really have major feudal holdings, only convents in the cities. So, you can’t really model the orders themselves as vassals. Instead, you might model the alignment of an individual monastery with land holdings with a spiritual movement as a factor affecting its political leanings.

“Holy Orders” is the established terminology for military orders in CK, yeah. Monastic orders are not currently modeled in CK3, although you could become a lay member of one in CK3 with the Monks and Mystics DLC.

Right, yeah, military orders. I was trying to distinguish between the Knights Templar and ordinary mercenary groups, but I guess those weren’t really orders.

Heh, maybe instead of a status bar or an abstract number, a character’s status could be displayed by a sort of Dorian Gray picture, with them getting more haggard and wretched-looking the further down their status goes. Like a more refined version of the Doom Space Marine’s health photo. Or an official state portrait getting progressively more defaced by vandalism and graffiti the more their popularity wanes.

I assume this is a response to my “getting the player to understand quantified fuzziness” point?

The problem isn’t finding some way to express a single variable in a way the player understands. Look at how the game handles opinion between characters—it’s a fuzzy social thing, quantified, then explained to the player. But it’s also a single social thing, not (for instance) an overlapping mess of duties and loyalties, which can be quantified as an array or somesuch, but which can’t easily be explained back to the player.

This is pretty much in the game. Your character’s appearance updates for various things like stress level and age, and also for specific traits you acquire like injuries/maimings, getting fat, becoming a drunkard, or contracting a venereal disease.

One that I love is that a character that is paranoid has an ‘idle’ animation of looking around them fearfully.

I have a few games in mind that try to simulate fragmentation (and some fuzziness) :

1.) The Revolutions mod for Civilization 4 :

Various variables (happiness, culture, religion, civics…) have an effect on empire-wide stability (empire size matters a lot !), but especially on the stability of the different cities (distance from capital matters a lot !).

And if they are not kept in check, you get various negative events that range from a rebel unit popping up, to some cities revolting and forming a new competing civilization, to even YOU being overthrown, which results not in a game loss, but in the AI playing for you for some number of turns (after which you supposedly manage to take the power back somehow), which IIRC also results in the stability situation having improved.

(I wonder how much it has influenced / been influenced by the 3 Crusader Kings ?)

2.) The “everything AND the kitchen sink” Caveman to Cosmos Civ4 mod :

https://forums.civfanatics.com/threads/caveman2cosmos-v42-player-guide.607564/

Relevant to the discussion are the new “city properties” : crime, disease, education, flammability, air and water pollution, tourism.

They are usually self-correcting, but crime and disease are *also* prone (by design) to self-reinforcing loops if left unchecked for *too* long.

One of the design goals was to try to make them “intuitive” to the player, rather than having him rely on math too much.

(Also includes the Revolutions mod, not fully integrated, so not particularly recommended yet, but some progress seems to have been done on that in the last few weeks ?)

Also important : includes the Flexible Difficulty feature, where the game is made more or less difficult for the different civs depending on where they are on the score leaderboard.

As you can imagine, this helps roleplaying a LOT, Sid Meier would be pleased !

3.) The new(ish) extra-planetary post-apocalyptic 4X / wargame Shadow Empire features not only population and worker happiness and soldier morale (and readiness), but also leader relations. A typical game will go up to several dozen leaders split over half a dozen factions. This is kept manageable for the player in that they actually don’t have relations between themselves (though they still compete in elections / politburo voting and attracting unaligned leaders), but only with “you” as the Holy Ghost of Empire typical in 4X.

Notably, most Decisions you take will please some of them and displease others.

Typically, this just results in lowered efficiency for whatever the leader has been tasked with, but if it gets low enough the leader can rebel, which can get *really* bad if it was commanding an important military Formation.

Otherwise, population can rebel too, but they just spawn outdated militia units, so after early game are mostly just a nuisance… except that you still have to be careful, because if that militia blocks an important rail line while you’re in the middle of a war and your troops are left too long without new fuel, ammo and food, this can effectively lose you an ongoing war !

(And there are various sabotage stratagems that allow you to effect all of the above in other empires.)

I really enjoy CK, but it’s always struck me that the core game is just Monster Rancher with enough ‘Grand Strategy’ decorations slapped on it to avoid alienating the wargamers who populate the rest of Paradox games’ playerbase. It really is amazing to see articles like yours illustrating all of the ways in which the ‘strategy game’ part of the game is actually a considered set of mechanics, and possibly even the intended core part of the game from the developers’ perspective.

Meanwhile I am completely dysfunctional at the long-term marriage game and everything to do with characters because I cannot remember them and spend most of my time on military conquest with fabricated claims or the non-claim CBs.

The “c” key pulls up the Character Finder. Just use the filters to make sure everyone in your Court is married, and check back every year or few months. Don’t worry about all the war and stuff, it’s just a distraction; either you’re strong enough to win effortlessly or you might as well let them get on with sacking you soonest. Eventually you’ll learn to use the Character Finder for everything from keeping children educated to making friends to moving your dynasty into India.

Actually in my current game the crusader Pope-Empress of Outremer and the head of the new and only true Christian faith, after having ended the Schism and imposed a matriarchy and shattered the mongols with a series of assassinations, is picking between crushing the major Catholic holdouts in Castille or marching on India.

The main problem at the moment is that because I went matriarchial on a whim the second Pope-Empress was not matrilineally married and has three kids of another house and is too old to make more and apparently instituting House Senority will not get you out of this.

Also on the military side, the difference between defending in a mountain with a river at full supplies and attacking into said mountain wnen your supply level is skull makes a remarkable difference and frequently turns the tide of war against superior opponents

In theory you should be able to use matrilinearity to get a same-dynasty grandchild and then murder all of the people in between, but at that point you might just decide you’ve won and move on to another run.

“In short, these are systems that resist simulation in general and particularly resist being reduced to game systems that in the end – because of how computers work – must be reduced to clear numbers rather than fuzzy distinctions.”

I think of this as a limitation of gamers rather than a limitation of computers. Too many interacting factors / knobs / systems and you go beyond the ability of individual players to hold the system in their heads and understand the predicted consequences of their actions, which is pretty central to what makes strategy gaming fun. There’s no serious software-engineering limitation preventing Paradox games from getting more complex; the complexity budget is more constrained by what makes a good player experience.

Yeah, everything can be reduced to clear numbers if you’re willing to get granular enough. The extreme case of this is something like Dwarf Fortress, where, e,g., a bug famously led to cats dying of alcohol poisoning because they kept grooming themselves after getting wet from spilled drinks in the tavern. Dwarf Fortress is also infamously difficult to learn.

I haven’t sunk my teeth into CKIII yet but I’m curious about how towns and republics work, and whether they might be a good template for these garrison towns.

They’re regular holdings, which take a penalty if held by non-republic (i.e all playable) rulers. Republics have a fixed contract, with potential bonuses based on culture and lifestyle perks, and successors are random dudes.

Basically, they don’t. They exist as individual barony-level holdings, distinguished only by having a mayor instead of a lord, but the county level is the lowest playable tier. Oh, there is also Venice- but that is non-playable, unless you conquer it militarily and convert it to a duchy.

Pedantry: They can exist on any level of holding, you just have to grant a mayor a title. County, Ducal, Kingdom and I guess technically Empire-level republics can exist.

I see two problems with adding complexity.

1. The problem with adding complexity is how you test this stuff. That’s actually a big problem with testing games in general, since the criteria for “correct” are often very fuzzy.

2. Do the extra things you’re tracking actually make a difference? This is a subclass of problem 1 because you end up having to trace out test cases where the extra things make a difference and then test them. If you put too many things in, you end up with a combinatorial explosion of things to test.

Yeah, the perils of High Modernism inherent in video games ?

https://samzdat.com/2017/05/22/man-as-a-rationalist-animal/

I think of this as a limitation of gamers rather than a limitation of computers. Too many interacting factors / knobs / systems and you go beyond the ability of individual players to hold the system in their heads and understand the predicted consequences of their actions, which is pretty central to what makes strategy gaming fun. There’s no serious software-engineering limitation preventing Paradox games from getting more complex; the complexity budget is more constrained by what makes a good player experience.

If you make the game too complex, it won’t run well on the average PC.

Oh no, your “average” PC is extremely powerful these days, you can totally make a game that runs well on it but is just waaaay too complex for your average player (Aurora 4X ?)

OTOH, both Aurora and Paradox games tends to start running like slugs after a while, even on powerful systems.

Yeah, in any case optimization vs developer effort is a tradeoff…

Nothing substantive to add, just seconding your recommendation of Tyranny, which was really good!

I daresay that Tyranny and Pillars of Eternity (especially Deadfire) are well due their own entries in the Teaching Paradox series (on a technicality; they are published if not developed by Paradox, and clearly model history more abstractly within speculative settings.)

In a sense, Tyranny is set in that part of Crusader Kings where you have to deal with establishing control and landing vassals, with the additional wrinkle that a bunch of vassals have just outlived their usefulness. Like, there’s a whole bunch of intrigue and inter-vassal backstabbing going on here and Kyros just wants the lot of them dead and pretty much attempts to murder two of them at the start of the game.

Deadfire does a really good job of exploring colonialism, perhaps moreso than any other game I’ve played that touches on the subject.

Crawls up from the underground caverns of pedantry.

Well ackshually, only the first Pillars of Eternity was published by Paradox (as well as Tyranny). Deadfire was published by Versus Evil.

Hisses. Crawls back down into the underground caverns of pedantry to resume hibernation.