This is the long-awaited first part of a series (I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII. VIII) taking a historian’s look at the Battle of Helm’s Deep from both J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Two Towers (1954) and Peter Jackson’s 2002 film of the same name. We’re going to discuss how historically plausible each sequence of events is and, in the process, talk a fair bit more about how pre-gunpowder (although we will actually get some gunpowder explosives!) warfare works.

Before we dive in, I want to remind old readers and notify new readers alike that you can support me on Patreon. If you want to register for email updates to know when every new post lands, you can do so by clicking this button:

These essays are mostly written on the assumption that you have already read the six-part Siege of Gondor series (I, II, III, IV, V, VI). While I will redefine some basic terms, for some of the concepts that we have already covered in that series, I will simply link back to the relevant discussion. If you haven’t yet read the Siege of Gondor series, that’s fine – where you might need some background, I’ll have a link to the right part of it, and so you can jump back, read that and then continue onward up the causeway to the Hornburg. This should also be perfectly readable if this is your first series and you don’t care to back up for the Siege of Gondor, although you may get a touch more out of it if you do.

Book Notes! As a reminder from the Siege of Gondor series, points where the books differ from the films in ways that impact our analysis will be covered in these little quote boxes as book notes. These are going to be more prominent in this series than they were with the Siege of Gondor. While the battle of Helm’s Deep itself has the reputation of being the more book-faithful of the two sequences, when it comes to a lot that we are going to talk about, like the operational context the differences are actually quite massive. At some points – and this post will be one of them – we’ll practically have two different analyses running in parallel.

Hopefully the distinctiveness of these little quote-boxes will help keep track of them.

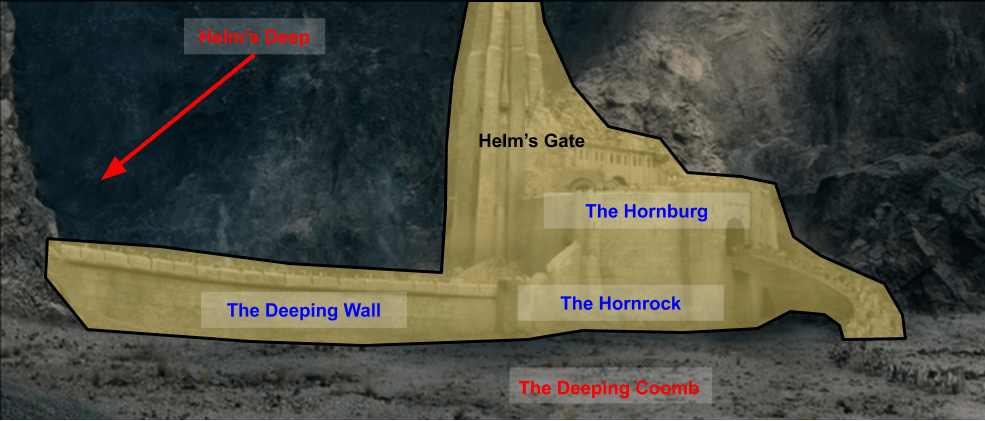

Finally, because the terms for some of these things are a bit imprecise. I am calling this the Battle of Helm’s Deep because that is, so far as I can tell, by far the most common thing people call it, although it might be more properly known as the Battle of the Hornburg or the Battle of Helm’s Gate. The film compresses this terminology, referring to the whole place as ‘Helm’s Deep’ without distinction. But since we’re going to be talking about this in some detail, the actual breakdown of names is going to be useful to keep track of what is happening where. For that, I am going to rely on the more detailed topography and naming conventions in the books, as follows:

Helm’s Deep is not actually the name of the fortress proper so much as it is the name of the gorge the fortress guards (this is quite clear in the text: TT, 157, “on the far side of the Westfold Vale, lay a green coomb, a great bay in the mountains, out of which a gorge opened in the hills. Men of that land called it Helm’s Deep…”). The fortress itself is called Helm’s Gate in the text and consists of three main parts: the main fortress, the Hornburg, a stone keep set atop the Hornrock, then the Deeping Wall, a long curtain wall closing off the gorge, and finally (book only) Helm’s Dike, a trench and earthwork wall out in front of the fortification. The Hornburg also served as the residence of Erkenbrand, master of the Westfold – a key figure in the books who is not present in the film (poor Erkenbrand is the second most hard-done-by character in the adaptation for being left out, after only Glorfindel-of-freakin-Gondolin who chivalrously lends Arwen his superstar appearance). That name, Helm’s Gate, neatly underscores the purpose of the fortress: it is a blocking fortress designed to forbid entry to the valley. The rest of the valley in front of the fortress is called the ‘Deeping Coomb.’ A stream runs from the Deep to the Coomb and is called the Deeping Stream. I am going to try to keep to these terms, if just to avoid a lot of confusion.

One more thing before we get started in earnest. One of the running themes of my look at Helm’s Deep – which will soon become very apparent – is that Saruman and Saruman’s forces make quite a number of avoidable ‘rookie’ mistakes, both during the campaign and the actual assault. I don’t want this to be misunderstood at a criticism of the source material. Rather, I think it is a hidden sort of genius to the source material. In our last series, we saw two very experienced commanders, the Witch King and Denethor (and also Aragorn, Faramir, and Théoden), engaging in very complex and quite masterful operations. There is a lot to learn from an analysis of a masterful operation (even a fictional one!) even when it is eventually unsuccessful.

But Saruman does not have a lot of experience. Théoden does. As Saruman himself notes, the house of Eorl has “fought many wars and assailed many who defied them” (TT, 218). Théoden himself had been a king even longer than Denethor had been steward (Théoden becomes king in 2980; Denethor becomes steward in 2984) and given what we know about the political situation, it is safe to assume he had some fighting to do even before he became king and much more afterwards. The film has Théoden say this, and at moments shows it on-screen in interesting ways, but the desire to insert some conflict between Théoden and Aragorn means that this characterization gets a bit muddled, as we’ll see. Nevertheless, it is clear that Théoden, in book and film, is an experienced and capable commander – he may lack the subtly and sophistication of Denethor (who, as an aside, I’d probably rate as the better pure tactician of the two, but the worse overall leader), but reliable workman-like generaling is often the best sort, and proves to be so here.

But as to Saruman – there is no hint in the Silmarilion that Curumo (the Maia who would be Saruman) was a great warrior among the Maiar (indeed, I cannot find that he did any war-fighting before this; his Maia name comes from the Unfinished Tales – he does not appear in the Silmarilion save as a wizard); he was a Maia of Aulë the Smithlord, and it shows. Saruman is an builder, engineer, plotter and tinkerer. Given his personality, he strikes me as exactly the sort of very intelligent person whose assumes that their mastery of one field (effectively science-and-engineering, along with magic-and-persuasion, in this case) makes them equally able to perform in other, completely unrelated fields (a mistake common to very many very smart people, but – it seems to me, though this may be only because I work in the humanities – peculiarly common to those moving from the STEM fields to more humanistic ones, as Saruman is here). I immediately feel I understand Saruman sense of “I am very smart and these idiots in Rohan can command armies, so how hard can it be?” And so I love that this overconfidence leads him to man-handle his army into a series of quite frankly rookie mistakes. After all, the core of his character arc is that Saruman was never so wise or clever as he thought himself to be.

So let’s dive in, starting with a look at the entire campaign as a whole:

Operations by the Book

Let’s start by reminding ourselves what we mean when we say operations. Operations is a level of military analysis that focuses on the coordinated movement of large bodies of troops to their objectives. It is a level of analysis between tactics (how do I fight the battle when I get there?) and strategy (why am I fighting overall?). Operations covers not only the time-and-space questions of moving forces, but also the logistics of moving and sustaining those forces (although, as we will see, the Helm’s Deep campaign is logistically much simpler than the Siege of Gondor) and crucially, of bringing dispersed forces together to maximize the amount of force at the moment of contact (which is to say, getting all of the armies to the battlefield at the same time).

Unfortunately, this part is going to be tricky to discuss, because the operational context of the film and the book are dramatically different. Théoden is leading different forces, for different reasons, to the same place, and Isengard’s timetable is unrecognizable between the two. So we’ll have to deal with each in turn, rather than in parallel. For once, I’m going to start us off with the book, because the operations there make a great deal more sense and it will give us a basis to understand where Jackson has run a bit off the rails.

Because the book is so different in this respect, we really have to split this analysis neatly in two, treating the operations in the book in their entirety (both laying out the events, and then analyzing them), and then moving on to the film. Fortunately this is by far the largest divergence, so we won’t need to do this again later in the series.

To understand that operational context, we have to first start with the strategic objectives that each side is trying to meet. Rulers and states do not merely smash armies together for no reason as in a children’s game: armies are sent to secure control over specific objectives. Battles result when two armies with competing objectives meet. Of course operational planning is more complex than this, but we must remember it is never less complex than this – it is very rare (not entirely unheard of, just rare) for someone to fight a battle for the sole purpose of fighting a battle. Almost always some object is being aimed for or prohibited (typically both).

So what are our objectives? In the narrowest sense, Saruman seeks to exert territorial control of Rohan and accomplish the destruction of its monarchy (note that this is a rather more limited and reasonable goal than his implied objective of human-genocide in the film). Théoden aims to stop him and presumably in the longer-term, destroy the power of Isengard. But there is a wrinkle to this in the more complex book narrative, in that both leaders are working within tight time constraints.

Saruman must know, as Gandalf does, that the blow against Gondor is coming soon (Indeed, by this point, it is not two weeks away – Gandalf reaches Edoras on March 2nd, and Minas Tirith is besieged on March 14th by an army that set out on March 10th, though this has been hastened somewhat by events). Saruman is not Sauron’s loyal servant though, and he is playing a dangerous game (cf. TT 221-2): if he expects to survive, he must be powerfully entrenched in Rohan before the last of Gondor falls – ideally, he hopes to have the One Ring as well. That urgency goes a long way to explaining his wasteful haste. The Witch King had spent many years preparing his army to assault Minas Tirith and his campaign – though unsuccessful – was masterful (and faced an equally masterful defense by the forces of Gondor). Saruman is in an awful hurry (and quite frankly, as we’ll see, not very skilled at this) and it shows in a slipshod operation followed by a disastrously unplanned and poorly executed fortress assault. It took massive outside intervention (Rohan! Aragorn! The Dead!) to throw off the Witch King’s plans, whereas Saurmon will lose decisively in a ‘duel’ (just Isengard and Rohan) without major outside interference (yes, yes – the Ents, but as we’ll see, for this operation, the Ents are actually superfluous, though they matter a great deal more for freeing Théoden’s victorious army to move East immediately), in a ‘war of choice’ he started. Saruman is skillful at many things, but his lack of craft in the handling of armies is going to be a theme here. Théoden, after all, has “fought many wars” (a film line that is a slight alteration of the book line quoted above) – Saruman has not, and it shows.

But Théoden also has strong time constraints, although it is not obvious that he is aware of just how tight they are (note this contrast with movie-Théoden who plays coy with what he’ll do until the last minute; book-Théoden knows that, strategically he has no choice – he rises or falls with Gondor and begins preparing to aid them the moment Saruman’s threat is clearly passed, cf. also Gandalf’s statement to him, TT, 144-5). Even before Théoden’s army leaves Edoras, Aragorn remarks to Éowyn in the presence of the king that “Not West but East does our doom await us.” (TT, 151) showing a clear awareness of the broader strategic situation. Théoden has to defeat Saruman rapidly enough to turn his army, march back over Rohan and make it to Minas Tirith for the second round he knows is coming. It’s not clear the degree to which Théoden understands exactly how narrow his window of action is at this early point, but once he has defeated Saruman, he begins the mustering process immediately without waiting for word from Gondor, suggesting he realizes is very narrow, even if he doesn’t know precisely how much.

We’ll get to some of the complications of terrain and logistics in a moment, but for now, I just want to give a basic rundown on the campaign. Here’s a map to follow along (note, this map doesn’t have distance measures; to measure distances not given in the text, I am using my own foldout map, which has a scale):

Tolkien’s dense writing along with the ample appendices in Return of the King enable us to reconstruct Rohan’s movements with a good deal of precision. On the early morning of March 2nd, Rohan has a field army, under the command of Erkenbrand of the Westfold covering the Ford of the Isen (which Saruman had forced on February 25th, resulting in the death of Théodred). But the main force of Rohan is in its cavalry, the largest body of which (around a thousand) is idle in Edoras, about 120 miles (40 leagues, TT, 154) east. Now you want to keep in mind as events unfold (very rapidly indeed) that none of these three armies – Saruman’s, Erkenbrand’s or Théoden’s – know where the others are or what they are doing at any given moment (in stark contrast, as we’ll see, to the film). They all make decisions or fail to make decisions based on part on that lack of knowledge – which is a regular feature of operations, especially in the pre-modern world. One often doesn’t know where an army is until one hits it (often leading to an ‘encounter battle’).

Following the appendix, Théoden marshals out of Edoras with his force first in the 2nd, intending to ride West, group up with Erkenbrand and give battle, probably at the Ford of the Isen. Théoden has ‘more than a thousand’ when he musters (TT, 152). That may seem small given the forces in our last series, but it is more than a thousand cavalry, which is actually quite formidable (and he expects to join up with Erkenbrand’s infantry, which as we’ll see probably number around 2,000). Théoden rides hard, moving until the last scrap of daylight is lost and beginning again in the early morning of the third (TT, 154). It’s a good plan; a ford is a good natural defense and as we’ll see, the likely combined force (something higher than 2,000 foot and 1,000 cavalry, given that not all of Erkenbrand’s forces reach Helm’s Deep – some died at the Isen Ford and some Gandalf redirected there to bury the slain) probably is large enough to risk an open battle, especially given Théoden’s commanding superiority in cavalry. Massive cavalry superiority covereth a great multitude of sins.

Meanwhile, later in the day (probably in the evening), Saruman’s force – which on foot has probably been on the march for a few days at least – reaches Erkenbrand at the Ford of the Isen late on the 2nd, defeats him and then disperses in pursuit and looting. Ironically, from an operational-analysis standpoint, this moment – which isn’t ‘on screen’ in either the books or the films – would probably be the moment identified later by historians and analysts as decisive. As we’ll discuss later in this series, Saruman’s forces disperse, pursuing fleeing pockets of Erkenbrand’s army and pillaging the countryside. This is a disaster – it prevents Saruman from engaging Théoden in the field (because he isn’t concentrated; note that Saruman’s forces have no reason to think Théoden is close by at this point, but still this lack of scouting is sloppy) or hindering his movement to Helm’s Deep, or effectively stopping the Ent’s march. And – as we’ll see – his forces mostly pillage so he doesn’t even complete Erkenbrand’s destruction. In essence, Saruman’s army makes itself profoundly useless during what turn out to be the most important 24 or so hours (from the afternoon of the 2nd to the evening of the 3rd) of the campaign. This is a common failing of armies: dispersing to loot and losing the opportunity to seal victory, but it is particularly striking here, where the victory is so incomplete. Amateur-hour indeed.

Théoden only finds out about this on the 3rd (by which point, Saruman is completely out of the command-loop because he has Entish problems and didn’t move with his army). Recognizing that his small force might now be overwhelmed in the field and himself unaware of Saruman’s disposition, he opts to move to Helm’s Deep, gathering scattered remains of Erkenbrand’s army as he goes. Helm’s Deep is very close – just a few miles off the road and perhaps 40 miles from the ford of the Isen at most – so he arrives the same day and begins laying in for a possible siege within the Hornburg. Because Théoden’s force is concentrated, he’s able to move through the diffuse cloud of Saruman’s raiders unhindered, since the small groups scatter at his approach rather than challenging him. Saruman’s army takes most of the day to reconcentrate and just misses a chance to engage Théoden’s rearguard before he reaches the Helm’s Dike (TT, 159). The out-fortifications prevent further pursuit until the assault begins after nightfall. Saruman’s only chance to force a battle in the field on favorable terms is lost, and the stage is set for his army’s disastrous assault on the fortress.

In terms of the distances moved, it is 40 leagues (TT, 154; that’s 120 miles) to the Fords of the Isen from Edoras, but Théoden doesn’t quite reach that distance. Instead, it looks like he perhaps rides 40 or so miles west on the 2nd, perhaps another 20 on the third, before turning for Helm’s Deep, perhaps another 30 miles away, covering maybe 100 miles or so total in two days of what is in effect a ‘forced’ ride (we’re told Théoden keeps the army moving through dusk until stopped by loss of light; TT 154). A hard ride, but within the capabilities of unencumbered cavalry moving over friendly terrain and known roads.

We are less well informed about Saruman’s army’s movements, except that they reach the ford on the 2nd and attack Helm’s Gate the night of the 3rd. Such a pace is brisk, but not impossible, particularly given how little we know about the position and disposition of the main infantry force of that army for much of the 2nd and 3rd. We should also keep in mind though that this force has been in the field for at least a few more days (perhaps three), since they need enough time, at minimum, to have marched from Isengard to the ford of the Isen, a trip which will take Théoden and a small, entirely mounted retinue a day and a half coming from the Deeping Coomb (such small cavalry forces can move much faster than infantry, three times as fast is a decent rule-of-thumb). And that assumes that this army set out from Isengard at that time, rather than having been in the field since the first battle at the Isen on February 25th.

(Fully) Operational Castles

When you describe an operation like I just did, it tends to fall out with a certain almost preordained majesty to it. Armies go where they always must have gone, mistakes are made where they always must have been made. The world runs like a fine clock, predictable and fixed. But it isn’t so, of course. In a real campaign everything is contingent and variable, swirling and unknown. This unpredictable “play of probabilities” is (part of) what Clausewitz terms friction, and the centrality of that concept (which I will not treat fully here; the exegesis of Clausewitz being a topic in its own right) should caution us against treating operational decisions and results as predetermined.

So we should start asking questions: why is the initial battle on the Isen Ford? Why does Théoden then retreat to a fortress (Helm’s Gate) even though he has the operational mobility to maneuver in the field to stay out of reach (remember, his force is almost entirely mounted) – and why on earth does Saruman’s army follow him there and give battle on terms so favorable to the defender? Answering those questions requires a bit of explaining and can help us understand the influence that castles – or potentially any sort of fortress – can have on operations, along with the role of uncertainty and imperfect information.

Let’s dispense with the easy question first: why does every army converge on the Isen Ford? In strategy games, the ‘overland’ maps often resemble vast plains dotted with key points (think of a worldmap for Total War or a Paradox game) but in operational planning – where armies need roads and supplies – the space for armies to move often more nearly represents a spider’s web of pathways, with key intersection points on them. Taking large armies off of major transit routes is slow and difficult; heavy wagons may not tolerate off-road travel well, it becomes difficult to get supplies, and it becomes very easy to get lost (remember, these armies may not have accurate maps, much less modern GPS – and pulling the army over to ask for directions from a hostile population brings its own perils). That’s not to say it cannot be done, but it tends to be avoided whenever possible.

The ford on the Isen is clearly one of those ‘points’ where the paths compress down to a single place. Saruman’s forces must cross it in order to get to Rohan; since Théoden can read a map as well as Saruman, he knows this. Moreover, a ford is far easier to defend than an open field – the ford is the natural position for both armies to try to occupy as rapidly as possible. Terrain can often create ‘hot-spots’ like this with many battles, because there are just only so many ways to get from Point A to Point B (which, remember – getting an army to Point B is the central concern of operations!), which is part of why battles often ‘cluster’ when viewed on a map. Saruman’s forces get to the ford first and force it easily, which is about the only bit of good fortune his forces will have.

And that brings us to the second, more interesting question: why do the armies converge on Helm’s Deep and then – more to the point – why do they then assault the fortress (Helm’s Gate) there? This in turn opens the broader question of how fortresses and castles shape land operations. Due to changes in the nature of warfare, fortresses don’t fill the same roles now as they did in the pre-modern or early-modern periods. Often, especially in stories, we assume that you siege the castle because besieging the castle is the doing thing – or because it is a ‘win’ condition in a video game (or because besieging the castle magically causes all of the smaller settlements in the area to effortlessly ‘flip’ to providing resources to you). We may dismiss this quite easily: no one engages in a siege – much less a fortress assault – if they don’t have to. But then why assault Helm’s Gate?

And here we get the error in the other direction – a very common one among modern folks looking backwards – in assuming that because a castle or fortress can’t possibly block the entire space (Hadrian’s Wall or the Great Wall notwithstanding) that such fortifications were folly: worthless and easily bypassed. But we can easily see why Saruman’s army must assault Helm’s Gate by gaming out what happens if they do not and that in turn serves to illustrate the purpose that many pre-modern castles and fortresses have. Because after all, there is nothing of value at Helm’s Gate, save for Théoden and his army.

(Note: I’m trying to be specific with my terminology, even though our sources are often not. Generally in modern usage a castle is a fortified private home, so compared to a more generic fortress it has an additional purpose, which is the protection of the home and the household within it. The bigger difference is between a fortress (of which a castle is a sub-type) and a fortified settlement or city. A fortified city contains the economic production and resources and population it is intended to both protect and control. Minas Tirith is a good example. By contrast, most fortresses are built to dominate the surrounding territory, rather than to protect an economic resource (read: city) they contain. Helm’s Gate, notably, has no economic center in it, and many castles didn’t either. I find it hard to decide if I should term Helm’s Gate a fortress, as its primary purpose is to block access to Helm’s Deep behind it, or a castle, as it does seem to also be the residence of Erkenbrand of the Westfold. In practice, the distinction matters little, but I’ve stuck with ‘fortress’ here.)

If Saruman’s forces look to spread out either pillage or – more likely – forage supplies locally, Théoden’s army is a serious problem. Whereas Théoden’s cavalry army can move fast with the supplies it can carry (for the distances here), Saruman’s force is on foot and has already been on the move for some time. As we’ve discussed before, armies on foot moving with supplies are often quite slow; from Isengard to the ford of the Isen River is about 30 miles (c. 3 days) before reaching Erkenbrand and defeating him on the 2nd. So by the following day, they’ve likely been on the road for four days (or nights, as the marching preference may be; and no, we ought not assume they move faster because of the Uruk-hai – for one, not all of them are Uruk-hai. There are men in Saruman’s army too, the Wild Men of Dunland). An army of this size might carry something like 10 days supplies with it, which means that Saruman’s forces are rapidly nearing their operational tether – they have to either gather supplies locally, get supplies moved to them along secure supply lines, or turn back. If they want to stay in the area to secure it or do economic damage, they must begin foraging.

Théoden’s army, with it strong core of 1,000 cavalry makes a mess these options. If Saruman’s army spreads out to forage, Théoden, now safely based out of Helm’s Deep, can use his cavalry to ascertain the disposition of the enemy infantry and – once he is satisfied they aren’t concentrated for a battle – ride out and destroy the foraging parties in detail (‘defeat in detail’ is the term for destroying a large army by engaging its separate parts in unequal contests one by one). In practice, the mere presence of Théoden’s army prevents Saruman’s army from foraging effectively (if you want to see this playing out in an actual ancient campaign, I recommend Paul Erdkamp’s Hunger and the Sword if your library can swing you a copy (or if you are just well-off) – this is the method the Romans used to bottle Hannibal up in Southern Italy after Cannae without fighting field battles with him). The threat of a cavalry attack will force the army to stay concentrated, which will prevent foraging, which will compel Saruman to retreat and try again – which he cannot do because, as mentioned, he is under tight time constraints.

Why not bypass Helm’s Deep? After all, it is off the road and thus not blocking a direct advance on the (now mostly empty) Edoras. Here, the problem is supply lines. If the army disperses, Théoden can pick it off in detail as discussed. But if the army is to stay concentrated, it needs a source of supply. As we’ve discussed before, supplying an army overland in the pre-modern period is very hard, but the distances here are small enough that it is possible. But Théoden is once again the problem – his cavalry, stationed just off the road in Helm’s Deep could easily dash out, disrupt those supply lines and dash back to the fortress before they could be engaged.

Striking at Edoras is equally hopeless, for the same reasons. If Saruman’s forces immediately march on Edoras, they have left not only Théoden’s force, but also the remains of Erkenbrand’s army behind them. Edoras is fortified with what Legolas describes as, “A dike and mighty wall and thorny fence” (which I read as a description of what is sometimes called Murus Gallicus after Caesar, B.G. 7.23, with a dry-moat on the outside). Not only can those armies raid their supply lines at will, they could easily show up behind the siege works by surprise and smash the whole host in the field. As we’ll see, an aggressive advance means leaving something close to 3,000 Rohirrim, more than a thousand of them mounted, behind you. To do so is to invite disaster – and on the open plains of Rohan with nowhere to hide or flee – destruction.

And this is how fortresses function on an operational level. The presence of even a small mobile force (here cavalry, though in rough country, light infantry can do the job) stationed out of a fortress (or a fortified city, especially if that city, as is likely, sits on all of the local transit routes like roads and rivers) tremendously complicates logistics and operations – much less any actual exercise in territorial control (like resource extraction) – in the lands surrounding it. Théoden’s cavalry makes his force impossible to ignore – it must be neutralized one way or another. And this is often how castles functioned in medieval Europe: the presence of cavalry forces (typically the castle’s lord and his retinue) within the castle garrison made both bypassing them logistically infeasible and exerting real territorial control around them effectively impossible. Consequently, if you wanted to take a region, that meant painstakingly reducing the major castles, one by one (thus, for instance, the strategic value of Stirling Castle which made it a repeated flashpoint in the wars between England and Scotland – sitting at the narrow of the island and along the River Forth, it simply couldn’t be bypassed, but had to be taken. Again. And again). If you were very lucky, the reduction of one major fortress might lead the others to surrender, which must be what Saruman is hoping for here.

Which leaves just a few options: you could attack the Hornburg (as Saruman’s forces do) or just leave a blocking force there and move the main army on to a real population center like Edoras. But leaving a blocking force isn’t simple: there may be something like 10,000 infantry in Saruman’s army (the movie’s figure), but they have to contend with 2,000 in the fortress and another 1,000 with Erkenbrand. That means splitting the army nearly in half to hold Théoden still. Moreover, while in the film, the Hornburg looks fairly easy to blockade, the fortress Tolkien had in mind actually looked like this:

Blockading that is going to require both circumvallation (building a wall around the fortress to prevent surprise attacks by the garrison) and contravallation (building a wall around your wall around the fortress to prevent surprise attacks by a relieving army – here Erkenbrand’s – from behind). That in turn means days of digging and earthworks where the army cannot be dispersed because you need half of it standing guard while the other half digs. All so that you can send the rest of the army onward while waiting Théoden out. And wasting all of that time just to be able to start another siege against a different fortification (the fortified town of Edoras) would drag the campaign out longer. And you still have the possibility that Erkenbrand’s army reconstitutes itself and shows up somewhere at the worst possible time, making Saruman wait even longer. Which, as we discussed, Saruman cannot do because his operational timetable is set by the impending destruction of Gondor and his need to present his occupation of Rohan as fait accompli to Sauron when the latter’s armies stream out of Anórien and up the Eastfold. The cautious course of waiting Théoden out, or engaging in patient siege-works simply aren’t available on the timetable that Saruman’s own double-dealing has locked himself into.

Book Note: that supply situation is briefly acknowledged in the text with the quote that I’ve used as part of the title for this post, when Gamling (temporarily in command of Helm’s Gate) quips that “If they [Saruman’s forces] come to bargain for our goods at Helm’s Gate, they will pay a high price” (TT, 160) – a delightful bit of bravado that didn’t make it into the film.

All of which points us to the reason that Saruman’s forces opt to assault the Hornburg: they quite literally have no other choice. The apparent predetermination here is a consequence of the fact that Théoden and Saruman’s commanders know all of these things already. Which in turn is why the failure of Saruman’s army to stay concentrated (something we will return to) at this juncture is so crucial – it causes them to miss their one opportunity to force a battle with Théoden out in the open and potentially settle the matter without a fortress assault.

Now that I’ve laid that all out, I somewhat wish that Tolkien had put all of that into the text. I quite think he intends us to understand all of that, at least if we are so bothered by the matter to consider it. And for most readers, the text presents no difficulties; these all seem like perfectly normal things for armies to do. And anyway, on a political level, focusing military resources at Théoden who is now the sole surviving member of the ruling line (and whose heir presumptive, Éomer, is riding with him) also makes sense. Driving the royal house to extinction often results in the rapid de-consolidation of a kingdom.

But I also think that Tolkien left some of this out because of the way he structures his dialogue, namely that pretty much all of it makes sense in-universe. People in The Lord of the Rings do not have “As You Know…” conversations, generally. And unlike at Minas Tirith, there is no naive, peaceful Hobbit here to have the matter explained to – only Théoden, Éomer, Aragorn, Legolas, Gimli and Gandalf, all of whom understand this all perfectly well without explanation. Unfortunately, we may not be able to include Peter Jackson in their number…

Operations in Film

The film’s planning and operational context are radically different and do not stand up to the sort of interrogation that the books do.

Rather than moving immediately as he does in the books after being awakened by Gandalf, Théoden stays in Edoras long enough (in the extended edition) to have an elaborate (and very emotionally stirring) funeral for his son, which makes sense from an emotional story perspective but perhaps not from a strategic one. He doesn’t have a large body of cavalry with him, because he has sent Éomer away and Éomer had ridden out with it. Théoden comments that such cavalry would be “300 leagues from here by now” which is strange, since Éomer’s goal was to fight Saruman’s forces, which should have him moving in the same direction (and also 300 leagues is about 900 miles, which would put Éomer somewhere north of Lothlórien or in the southern reaches of Mirkwood).

After the funeral, Théoden receives word that Saruman’s forces are already in the Westfold – meaning they are over the Isen and are burning the place (some orcs had slipped through in the books in that first attack in February, but were crushed by Éomer in the open). Gandalf advises attacking Saruman’s army ‘head on’ – a terrible plan as we will see – but Théoden (wisely!) refuses. He instead resolves not to go into open battle, but instead to take the populace of Edoras to Helm’s Deep, emptying the city. What is communicated to us here and later is that this body of refugees, combined with the people already at Helm’s Gate comprise “the people of Rohan” or some very significant fraction thereof. His route is described by Wormtongue as “a dangerous road to take through the mountains” which – look at the map – it is not (it is, rather, a brief jaunt down the one main road Rohan has)!

Book Note: I want to just stress how different this situation is. Gandalf and Théoden in the books are are on the same page, first planning to meet the enemy in the field after meeting up with Erkenbrand, and then it is Gandalf who suggests the retreat to Helm’s Deep. Moreover, the composition of Théoden’s column has changed, with hundreds of cavalrymen subtracted out and what is presumably many thousands of refugees added in, which would dramatically change the speed at which his force can move. Crucially, in the books, the civilians of Edoras are left in Edoras (they actually make for Dunharrow, another mountain fastness, more sensibly away from Saruman), with Éowyn put in charge of them. Finally, of course, Éomer has been removed from the army and Erkenbrand and his army (an infantry force) has been removed altogether.

Gandalf immediately complains about this plan and – you know what? – he’s right! This is a terrible plan. Théoden’s response to hearing that the Westfold is being pillaged by enemy forces who have already crossed the river is to lead a column of refugees into the Westfold, where the pillaging is to seek safety in a fortress that is closer to the enemy. His plan is to avoid open war and a pitched battle by marching to where the enemy is. He even insists to Gamling that “this is not a defeat” which makes it sound like he is retreating from the enemy, but even a brief look at the map tells us it is not so:

But Gandalf’s plan is no better! Théoden’s force is much too small to offer open battle to the army we later see (an army that Gandalf should have some sense of, having witnessed its initial creation). His forces aren’t even enough to really compel that army to concentrate and thus stop pillaging and burning. And some of Gandalf’s information is just wrong – he insists of Helm’s Deep “there is no way out of that ravine” which is most certainly not true in either the books (TT, 158) or the film. This is a strange error for the wisest of the Maiar to make (and thus, unsurprisingly, it is not in the books).

But not only does this change make both Gandalf and Théoden into fools, it makes a complete mess of the logistics and operations of the campaign. It is hard to pin the sequence down precisely as the film plays fast and loose with time as well as geography: In the close shots, it looks like afternoon when Théoden leaves Edoras (everyone is casting deep shadows), but in the wide shots, the sun is still high in the sky (presumably for lighting reasons); then we cut to Wormtongue already at Isengard telling Saruman what has happened. We might dismiss this as just film playing with time except that this scene ends with Saruman ordering out his Warg riders who then reach Théoden just a few scenes later. But strangely, this scene seems to take place at a mid-day lunch stop, so perhaps Théoden left Edoras in the morning?

Either way, we have our wolf battle. Then (at the same time?) the civilian column reaches Helm’s Deep and begins settling in. Saruman, presumably knowing his effort to strike Théoden on the road has failed (presumably a warg rider has reported back?) sends out his vast, uniformly infantry force to attack Helm’s Gate (he says “Helm’s Deep will fall” but I think this is because Peter Jackson, for the sake of not confusing the hell out of us, drops many of the geographical names or condenses them) and explicitly tells them “this night the land will be stained with the blood of Rohan.” His army then apparently powerwalks around 120 miles or so in an afternoon to arrive at nightfall.

This is a mess. To be clear, Helm’s Deep is about equidistant between Edoras and the ford of the river Isen, putting it about 60 miles from both. In the time it takes Théoden to cross that distance, Wormtongue rides from Edoras to Isengard (minimum 160 miles), a cavalry unit is marshaled, sent out, it rides probably 120 miles to Théoden, fights a battle, loses, the survivors ride another 120 miles back to Isengard, where an infantry force is then sent perhaps 100 miles to Helm’s Deep, arriving later on the same day as Théoden. All of which apparently happens in the space of a day or two, while Théoden is moving a column of civilians, loaded down with children, the elderly and supplies. I am beginning to think Euron Greyjoy got his teleporter used from Saruman’s ‘going out of business’ sale. Needless to say, these travel times are unrealistic.

With a column of civilians, it ought to take Théoden no less than six days to reach Helm’s Deep. Moving a line of refugees ten miles a day is actually a rough pace when many of them are likely young or in bad health or loaded down with supplies. Logistically, that trip is very possible; people can carry around ten days of food on their persons (we see nothing like a wagon train here). Meanwhile, assuming everyone rides fairly hard (40-50 miles per day), it ought to take Wormtongue three days to each Isengard, then another two-and-a-half days for the Warg riders to reach Théoden, then around two-and-a-half days for them to report back, then perhaps five days for the Uruk army to reach Helm’s Deep. Meaning the main army should arrive 13 days after Théoden and Wormtongue left Edoras. There is, quite frankly, within the geography of this movie (and before anyone argues – as the Game of Thrones apologists are want to do – that the scale is different, remember they show us a map at the beginning of Fellowship, and it is the same map) no way for this campaign to make sense (and that’s without Éomer teleporting 900 miles to the north in a day and then back again). There is little purpose to checking the logistics either – as a rule, when an infantry unit moves a hundred miles in a day, I do not ask “how much food did they eat” but “how much gasoline did their trucks use?”

And Saruman’s new plan, which isn’t to rule Rohan, but to destroy it, – including, as both he and Aragorn make very clear, all of its people, also makes no sense. Who is going to farm the land to feed your armies? The Uruk-hai? And Théoden’s claim that he can ‘outlast’ Saruman “within these walls” is also nonsense – he has brought a huge number of refugees (presumably) and likely arrives with only a few days of food for them. Given that, when they arrive, there are already lots of refugees at Helm’s Gate, it’s hard to imagine he has more than a few weeks worth of food, at the most.

I’m honestly quite put out that Jackson makes such a hopeless tangle of this sequence, because it is sufficiently tangled that I cannot really use it to explore any interesting historical concepts. It is not possible to fit a meaningful percentage of the populace of Rohan (a kingdom covering something like 40,000 square miles; taking the low-end estimates for density in medieval France, we might expect something like 1.6-2.5 million people to live in Rohan) inside of a single fortress of this size. It is not possible to feed those people once they are there. It is not possible to move them this quickly, or for Saruman’s armies to move this quickly. And the operational goals of both sides now make no sense – Théoden seeks to avoid a battle by marching his civilians to his enemy’s doorstep while Saruman seeks to extract resources from a kingdom by exterminating its productive peasantry.

Fortunately, the rest of the film’s treatment holds closer to the book and as such is quite a bit better.

Conclusions

I think there’s one question left to be answered here, and that’s why Peter Jackson? Why? And I think we can answer this question, because while Jackson’s arrangement makes about no military sense at all, in terms of film construction, it makes a lot of sense.

Peter Jackson comes into this sequence with a load of problems. First, there is a pacing problem. Helm’s Deep is just not a massive sequence in the books to begin with (it is all over in a single chapter), but as a film, Two Towers needs a rousing conclusion. So while the narrative of the book builds to the brutal and brilliant cliff-hanger of “The Choices of Master Samwise,” the film cannot end without some sort of hope-spot, which has to be the victory at Helm’s Deep, magnified in scope (which is why the events of “The Voice of Saruman” are moved to the next film, even in the Extended cut) and then paired with Frodo and Sam crossing back into Ithilien. That means the battle has to be bigger (to be the big movie-ending climax). But that creates another problem, because now Helm’s Deep is not in the middle of the narrative, it’s at the end. So you have a three hour movie with one good action scene…at the very end. So you need an action bit somewhere close to the middle, to keep the audiences’ attention – thus the warg battle. These are just consequences of the different ways films and books are paced.

We add to this a second problem: too many characters. Théoden, Éomer, Eowyn, Erkenbrand, Háma, Gamling, and Wormtongue are all new – in addition to Aragorn, Gandalf, Legolas, Gimli, Merry, Pippin and so on. It’s too many for a film. I can’t help but notice that Háma and Gamling’s roles (despite being two actors and two characters who occasionally are on screen together) are effectively merged (to the point that, when speaking to Saruman later, Théoden can’t remember where exactly poor Háma died; he is killed by Wargs in the film (we see him scream and cover his face as the warg leaps in for the kill) but slain at Helm’s Deep in the books; film!Théoden reports the later to Saruman in his speech). Erkenbrand has to go – his part will be played by Éomer.

(As has been pointed out, Háma does show up, without lines, in the backgrounds of some of the Helm’s Deep battle scenes (like the so-it-begins-scene), but I think this is just an extension of the error. The film language of the Warg attack is very clear – his lifeless body is tossed out of frame. And then Háma pointedly isn’t with Théoden (and there is an extra standing in his place) as the fortress prepares for a siege. Both of the wikis (here and here) list him as dying in the Warg attack. I think this is probably the product of script revisions and a need for lots of people to fill out scenes in the battle)

Peter Jackson has another problem: the Two Towers has exactly one speaking female role, and the story meets her in chapter 6 (“The King of the Golden Hall”) and leaves her – not to return until the next book/film – in chapter 6. This isn’t just a representation problem (although it is that), this is a crucial character – we need to set up her goals, character and motivation, because her character journey is really important in the next film. And films have to be much more economical with screen-time than books with pages, so Éowyn has to be on camera for longer in order to get that done; so her part must be expanded, which in turn means we cannot leave her behind in Edoras – because we have no reason to take the viewer back there. So we have to find an excuse to bring Éowyn with us to Helm’s Deep, but also not have her do any fighting, because that’s the core of her conflict in the next film (but we also can’t have her do nothing, because that cuts against her character too).

While I’m sure there’s a lot of great symbolism in that moment, I have to imagine Éowyn, who quite likely spent weeks carefully embroidering that banner, or ones just like it, herself is too busy being angry at losing such a carefully made piece of art to notice them.

Also, I have to imagine, had she known that Aragorn, upon seeing such handy-work fall past him as he entered the gate, rode past and did nothing, she might have been a touch less enamored of him.

And on top of that we have a fourth problem. The stakes of the battle of Helm’s Deep in the book are expressed in complicated, slow dialogue – and even then, only incompletely. I’ve just spent the better part of 4,500 words explaining why this battle works out the way it does, why that makes sense and why the stakes are what they are. Jackson needs the stakes to be bigger, but also more immediate – ideally he needs them visually on screen, because film is – above all – a visual medium. Jeopardy that only exists in dialogue is bad jeopardy in a film. This needs to be obvious and immediate and it needs to be established quickly because, good heavens, this film is already really long.

Jackson’s solution slays these last two problems with a single stone. By moving the people of Edoras to Helm’s Deep, he takes a jeopardy that existed only in the abstract and brings it on screen (and also makes it more comprehensible, since we do not need it explained to us that the fall of a fortress would be bad for the people in that fortress). And at the same time, this takes his one key female character and keeps her where the plot is, so he can establish that she wants to fight, but keeps getting shoved aside. This is a point he has to hammer repeatedly so that the audience remembers it a year later (remember, he’s planning these films for theaters before the Age of Marvel when you could rely on Wikipedia to bring your audience up to speed) when that character development gets resolved in the next movie. And it gives her something to do that shows her being practical and compassionate, which we also need demonstrated clearly.

So while mashing the operational context of this sequence into unrecognizable mush saddens me, I have to say I honestly cannot see a better way to do it while still resolving these problems, keeping in mind the strict restrictions on screentime (which makes adding an Edoras-Éowyn B-plot – technically a C-plot, since this is the B-plot to Frodo’s A-plot – effectively impossible). Alas that it came at the cost of my beloved logistics studies, but as far as sins of adaptation go, this one is a reasonable and necessary evil.

Next week, we’ll start the action proper by taking a look at Théoden’s trip to Helm’s Deep and the additional film action-sequence of a cavalry-on-cavalry engagement (a surprisingly rare thing to see in film, despite how many times the cavalry rides to the rescue).

Amazing analysis! I’ve been looking forward to this since reading the Siege of Gondor. One minor nitpick: Hama actually survives the warg attack! You see him at the beginning of the Battle of Helm’s Deep, next to Gamling (both behind Theoden). You can look up the “So it Begins” meme. I will be looking forward to next week’s addition.

I noticed that too. I think it is a part of the same problem. The film language of the wolf attack scene seems unambiguous to me – we even get a moment of clarifying whose who at the beginning of the scene. Then Hama gets slammed off of his horse, then he screams as the warg closes in, then we switch to his point of view as it is enveloped in the warg’s mouth. Then we *see the Warg toss him aside*…by his *head*. Just casually tossed out of scene – he doesn’t even make a noise to tell us he’s still alive.

It’s hard to keep track, because Gamling and Hama look so damn similar, but I will note that both wiki’s (https://lotr.fandom.com/wiki/H%C3%A1ma and http://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/H%C3%A1ma ) follow my reading of the scene. And Hama is missing from some obvious scenes he *should* be in during the preparation for the battle. And then, boom, there he is.

I suspect this is a product of script revisions, but I don’t know. I’ll make a note in the main text.

That wouldn’t be the only script revision during the Battle of Helm’s Deep. Jackson wanted to do the same thing with Arwen that he did with Eowyn here, keep her in sight for the audience to remember her and keep track of her character development. Arwen was originally supposed to journey with Elrond to Lothlorien and both had scenes filmed with Galadriel (with the dialogue being repurposed into a telepathic Skype call between Elrond and Galadriel). There even are a couple of long shots at Helm’s Deep where Arwen can be seen fighting alongside the Lothlorien archers. Arwen’s role was eventually cut – probably because he figured it made too much of a mess of things and did little too explain why she didn’t stick with Aragorn after that battle.

It’s 10 to 1 that Hama was meant to survive the Warg attack and die at Helm’s Deep, but Jackson forgot about him and decided to toss in his death during pick-ups because he thought that the attack didn’t appear brutal and costly enough to Theoden, thus creating the continuity error.

I have the extended edition dvds, and the person standing behind Theoden, next to Gamling is some random guy, not Hama. Maybe they changed it? I don’t remember ever seeing Hama again after the warg attack. (Also the film has that scene of Aragorn with Hama’s son at helms deep before the battle, I always assumed Hama’s son has lost hope because his father was killed by the wargs)

Just a quick nitpick on the use of fortified positions.

As far as I understand the use of medievals keep was also in many case just to keep something precious.

Be it a hostages, familly member, a treasure room or vast supplies. All kind of things you don’t want to risk in a risky encounter battle.

So if the Hornburg doesn’t protect anything of startegic value per see, as a city, it could very well be an haven for the populations and harvest of the whole Westfold. Sus forcing a quick siege if any invading army want to substain itself by foraging. And as you say without foraging the operational lifespan of an ancient army is often fairly small.

Limiting the opportunity of a drawn out siege.

That’s a good observation. I can imagine the Hornberg filling up with refugees from the countryside fleeing the pillaging orcs. It would have given Theoden’s army a civilian population to defend without the nonsense of bringing along the entire population of Edoras.

And this happens in the book. I was going to note it later in the series, but Gamling indicates to Theoden when the latter arrives at Helm’s Dike that the people of the Westfold have been fleeing to Helm’s Gate, “a third part” he says. But I suspect Jackson was worried that in a film where everything needs to be so much clearer, it would get muddled who *these* refugees were and why they weren’t *those* refugees over there.

Those that escaped did. (Since Theoden talks of the deaths when repulsing the offers.)

A bit of pedantry from a long-term Tolkien fan: maia is singular; maiar is plural. Please, please put it right; it’s bad enough seeing it from 16 year old Legolas fans on facebook groups, but you are aspiring to the proud badge of pedant 🙂

Fixed

“Éomer’s goal was to fight Saruman’s forces, which should have him moving in the same direction (and also 300 leagues is about 900 miles, which would put Éomer somewhere north of Lothlórien or in the southern reaches of Mirkwood).”

He went off to fight the Uruks that turned Northeast (to head towards Isengard). 🙂

And found them, and defeated them, and then moved on, all of which Aragorn knows. Again, the problem here is that in the books, Eomer encounters Aragorn riding *back* from defeating those orcs, heading towards Edoras. Whereas when Theoden declares that Eomer should be 900 miles away – which again, is an absurd, silly distance – no one challenges him.

And in any case, at 300 leagues, he’d have reached Isengard twice over with room to spare. The problem is the distance and Theoden’s declaration that Eomer was too far away to recall.

Oh, my mistake, forgot those orcs had already been defeated. I was simply commenting on the poor grasp of geography in the film to begin with, as Legolas’s comment should indicate that they were taking the hobbits to Dol Guldur (which doesn’t make much sense either) based upon their rough location instead of Isengard.

Might it be that ‘300 leagues’ might be a Rohirrim equivalent for “a thousand miles” in the sense that myriad literally means ten-thousand but was also a stand in for “indefinitely many”

I think in context they would be precise — it’s not like the distance was not a significant consideration.

Based upon your previous discussions of the use of cavalry, how they are not “battering rams”, and their need for room to maneuver, I’m really looking forward to your analysis of the end part where Eomer and Gandalf charge in a tightly packed formation down a deeply inclined slope towards a wall of orcs.

I wonder if the mid-movie warg raid sequence could have been replaced with an attempt by Eomer (I agree that replacing Erkenbrand is probably necessary) to retake the Ford. You could even have him appear to succeed but then be overwhelmed by the fresh armies marching from Isengard and order a retreat. That establishes that he’s out somewhere nearby rather than 300 leagues away while still taking him off the board, so to speak, until it’s time for him to ride to the rescue.

Fab analysis as usual, Bret. The proof-reader in me wants “Glorfindel” rather than “Glorfindal”. I particularly like your reasoning of why Peter Jackson had to do it that way – I must remember to think more about these whys, when looking at war films. Though that can never excuse any of the Battle of the Bulge film, I fear.

Saruman as STEM supremacist is a brilliant and delightful comment on his character.

I believe it is a controversial question among Tolkien pedants as to whether Glorfindel (LotR) is the same character as Glorfindel (Silmarillion).

You explain why Theoden retreating to Helm’s Gate pins down Saruman’s army, I don’t think you quite explain why keeping his army in the open wouldn’t do so equally effectively, given the premise that Theoden can successfully keep his army out of Saruman’s reach.

As a bit of a tangent: regards the possible battle at the ford, you say massive cavalry superiority covers a multitude of sins. From what you’ve written about cavalry tactics in the past I get the impression that shock cavalry (i.e. not steppe archers) is reliant on inducing morale or indiscipline problems to defeat melee troops, and would be largely ineffective against sufficiently well-drilled infantry in a deep formation. I presume in the specific circumstances, even Uruk-hai couldn’t be well-drilled in a deep formation while crossing a ford, but what about more generally? Can even well-drilled infantry with good cohesion not be relied upon to hold ground against a cavalry charge? If you run out of other topics I’d be interested in a discussion of how non-steppe-archer cavalry was used against infantry, especially medieval heavy cavalry. (I think your treatment of non-steppe archers so far has largely been governed by why visual media cavalry tactics would be a disaster in practice, which may be the reason for why you seem to be playing down cavalry effectiveness in past posts.)

Tolkien never got real precise about how elves are reborn.

I suspect that the multitude of sins covered depends on the distances those cavalry forces need to cover. There’s a horse versus man race in Wales, and while humans tend to win in hotter temperatures and over longer distances, horses beat humans handily in cooler temperatures over shorter distances. If I understand Bret correctly, it appears that speed and shock to morale rather than endurance is the real advantage of cavalry.

A cavalry force could strike out at high speed over short distances and inflict massive casualties on a disorganized looting force. A thousand-strong cavalry force moving over friendly territory for a short period of time could cover large distances very quickly, especially with fresh changes of horses and an easy supply of horse fodder and locally available food for the men. Over long distances in enemy or neutral territory, that’s a different ballgame.

Not really an experienced tactician or anything, but consider the two possibilities:

1. Theoden harasses the orcs in the open. He can’t engage decisively without great risk if they’re concentrated, since they outnumber him. He will have to camp in the open, and face night attack in the open–orcs are perfectly comfortable moving in the dark. If they’re still in dribs and drabs, he can defeat in detail, but that requires him to hunt all over Rohan for orc bands, and arrange to keep orc-snuffer squads of whatever size fed and watered wherever they go. Rohan is huge. Also, Theoden is short on time and the wretched creatures will scatter. Any missed pockets of orc will do something horribly antisocial so Theoden will have to ensure that no significant number survive.

2. Theoden retreats to a fortress where he will have a built-in defensive advantage and won’t have to move stuff around. The orcs and such will still have to come to him, with besieging force, and his riders are perfectly comfortable guarding a fortress.

The blog post asks “Why does Théoden retreat to a fortress?” but never offers a convincing answer. Theodens strategic goal is to defeat Saruman quickly and ride west for a confrontation with Sauron. To do this, he should have stayed in the field. He could achieve defeat in detail and didn’t really risk much. Clausewitz wrote that cavalry force can not be decisively defeated by infantry because infantry is unable to pursuit cavalry. By contrast, decision to hide in the fortress was silly. He risked blockade and prolonged siege which would allow Witch King to execute his plan.

IMO, Sarumans core forces were not dispersed. He could send his auxiliaries to pillage while his main force marched on Helm’s Gate. Also, I think Theoden didn’t have cavalry superiority. I learnt from your earlier blog posts how horses fear elephants. They fear wolves much more so a small warg force could deny any cavalry attacks. That would really compel Theoden to seek refuge behind walls.

Kwoz, I think we need to remember that Theoden is king of Rohan, not just a military commander. He has to look after the civilian population and minimize their casualties. Helm’s Deep is one point where there are lots of refugees in need of protection.

And I think you are overlooking the point Brett made about castles being the base for cavalry operations. A cavalry raiding force can’t stay in the field indefinitely against vastly superior numbers, they have to have somewhere they can make camp and sleep. Unless Theoden can defeat the entire Isengard army in one day, he really needs to preserve and garrison Helm’s Deep.

Hi scifihughf, you make a good point that protecting the population is another objective for Theoden. But that’s one more reason not to go to the Helm’s Deep. Terrain makes it easy to block the only access road to it with earthworks. Bret wrote that the castle is a base for small scale cavalry operations (lord and his men). Bret also wrote that in the books this castle is a residence for a lord and his troops so it was garrisoned. I still think that if Theoden really had cavalry superiority he should have stayed in the field and use his mobility to attack at will. That way he could prevent pillaging by forcing Sarumans forces to stay concentrated or rescue Helm’s Gate if needed. Or another castle – there must have been other castles because Bret also wrote that a single fortress couldn’t protect any significant part of the population of Rohan.

Glorfindel is the same elf as the one in Silmarillion. Tolkien makes it clear in the last volume of The History Middle Earth XII “The Peoples of Middle Earth” if I remember correctly. Tolkien is quite clear on how the elves are reborn in the text “Laws and Customs among the Eldar”.

>”You explain why Theoden retreating to Helm’s Gate pins down Saruman’s army, I don’t think you quite explain why keeping his army in the open wouldn’t do so equally effectively, given the premise that Theoden can successfully keep his army out of Saruman’s reach.”

He can keep out of Saruman’s reach during a raid, but that doesn’t mean he can keep out of reach forever. He’s still outnumbered about three to one, even counting his infantry, and his men have to sleep some time. The fortress gives him a secure location where he can rest his forces in between raids out into the countryside to sweep up dispersed, pillaging Uruk-hai or strikes against Saruman’s supply line if he tries to push his army on to Edoras.

Without the base at Helm’s Deep, Theoden is vulnerable to any Uruk-hai infantry regiment that manages to catch up with his raiders during the night. Since the Riders of Rohan don’t have the Roman-style knack for constructing a little fort wherever they go to camp for the night, that’s a problem. Theoden can compensate for that by using his cavalry’s speed advantage… but only for so long.

In other words, Theoden doesn’t want to stake literally everything on being able to keep out of reach of Saruman *indefinitely.* Not when Saruman has a bigger army of *relatively* tough, tireless infantry, and in theory may have weird magical forms of communication and coordination.

============================================

>”As a bit of a tangent: regards the possible battle at the ford, you say massive cavalry superiority covers a multitude of sins. From what you’ve written about cavalry tactics in the past I get the impression that shock cavalry (i.e. not steppe archers) is reliant on inducing morale or indiscipline problems to defeat melee troops, and would be largely ineffective against sufficiently well-drilled infantry in a deep formation. I presume in the specific circumstances, even Uruk-hai couldn’t be well-drilled in a deep formation while crossing a ford, but what about more generally? Can even well-drilled infantry with good cohesion not be relied upon to hold ground against a cavalry charge? ”

Oh, realistically Saruman’s infantry can *definitely* hold their ground against Theoden’s cavalry. The problem is that in this specific case, that just means the Uruk-hai can hold the specific patch of land they’re personally standing on. That works great as long as the Uruk-hai stand in (loosely speaking) a phalanx and bristle menacingly at the Riders of Rohan, but it falls apart if they try to either spread out into the countryside, or form up into a column to march on another target.

The fact you have to turn the operations into nonsense to maintain pacing, is yet another reason that I think the TV series, not the theatrical-release movie, is the ideal medium for adapting book-length fantasy. You can allow for a slower buildup in a series. (Game of Thrones exacerbates weaknesses in its source-material—though it wasn’t the showrunners who didn’t know how big a 500-foot wall is, that was Martin—but a Lord of the Rings adaptation would have better stuff to work with.)

Certainly the Dune miniseries did a better job than the movie, in most respects, despite having a fraction of the budget ($20 million in 1999 vs. $45 million in 1981—which comes to c. $31 million and $128 million, respectively, in today’s dollars).

At the same time, I have to credit Martin for keeping track of the distances and associated travel times in Westeros far, far better than the showrunners did. When the showrunners adapted the early seasons of Game of Thrones, they kept the army movements and timetables far more realistic (apart from Littlefinger, who either had a jetpack or a teleporter). It’s in later seasons that have armies teleporting across Westeros and Euron Greyjoy turning into a Diabolus ex Machina at every possible juncture. So a TV series may give more time to show this sort of thing, but it means nothing if the showrunners and writers don’t know how to make sense of it.

The GoT example makes me wonder why Peter Jackson couldn’t have stuck to the original troop movements here. Agreed that film is a primarily visual medium, but surely they could have distinguished between the refugees at Edoras and those at the Hornburg? Like, for instance, have a bloodied and wounded rider come to Edoras to warn Theoden of the pillaging going on, have Theoden ride out with his all-cavalry force, and then come across dirty (but not wounded) men, women and children fleeing to Helm’s Gate? You’d have both visual confirmation of the rider’s message and a sign that things are worse than expected. (Easier said than done talking from a chair, of course, but it’s not like said visual separation like that’s undoable)

As pointed out in the article, the big reason is that if the Edoras population stays in Edoras, Eowyn gets written out of the final scenes of the movie. Not so good.

On the subject of cavalry-vs-cavalry engagements, I wonder if you have any interest in looking at Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven (the director’s cut, not the butchered theatrical cut). It features a cavalry on cavalry engagement in the middle of the film and some good (for Hollywood) awareness of logistics. It’s also just a beautifully filmed movie.

It is on my list!

Awesome! Looking forward to it!

Much of Denethor’s alleged superior subtlety over Théoden stems from his access to a Palantir, even if it is filtered for maximum morale-destroying effect by Sauron.

I’d tend to disagree. Denethor is managing a much larger kingdom, in a much more complex military and political situation, and doing so fairly well. The Witch King is a far more dangerous adversary than Saruman – Gandalf (the White) straight up punks Saruman, but the Witch King advances on him with some confidence (though Gandalf doubtless proved stronger) and if you read the unfinished tales, Saruman feared him too. Minas Morgul’s forces appear to be something like an order of magnitude larger than Isengard’s.

And Denethor is running a much more complex military operation, with multiple independent commands, forward irregular forces, a complex muster system, blocking at least three key access points (Pelargir, Osgiliath and Cair Andros). Theoden is good, but nothing he does is so difficult or so masterfully done as the delaying action in the retreat from Osgiliath – you can read my analysis of it in the Gondor series. That is not all, or even primarily, up to the Palantir.

And that all plays into what we are told. Gandalf *says* of them that “Theoden is a kindly old man. Denethor is of another sort, proud and subtle, a man of far greater lineage and power, though he is not called king” (RotK, 26). Gandalf is the setting’s (semi)divine spirit of wisdom – we ought to trust his judgment.

It’s an observation as old as Plato’s Apology of Socrates that it tends to be a common flaw among humanity in general.

In particular, I have, as a computer programmer, only once received requirements that actually violated the laws of physics but many, many, many that were logical contradictions. (Why on earth would copying the data mean that changes to the original do not just APPEAR in the copy? It’s a computer, it should just HAPPEN.)

Besides Saruman himself being new to war, there’s also the matter of his battlefield commanders, as compared to those of Sauron. Sauron has the millennia-old Witch-King and his lieutenant Gothmog, who presumably had been fighting Gondor for years. Isengard’s leaders, meanwhile, are unnamed, and at least in the movies appear to be weeks or days old.

Martin Pearson described Saruman’s army as “heavily armoured toddlers” for exactly that reason.

This is a chance to strongly recommend fans of the books and films to locate Martin Pearson’s “Unfinished Spelling Errors of Bolkien” CD. It’s a very funny summary of the films interspersed with equally funny songs – “The Saruman Song” specifically for the battle of Helm’s Deep. Like Galaxy Quest it isn’t mean or mocking, made by and for people who love the original.

I don’t have the book right next to me at the moment, but I remember one sentence that calls Isengard a “child’s plaything, a mockery” of Barad-Dur and its giant industrial facilities, so the description of Saruman’s commanders as infants fits perfectly. By the end, everything goes to show that Saruman is simply a petty and childish imitator of evil next to Sauron, who has had millennia of experience working alongside the original Dark Lord and Satan equivalent, Morgoth. Even when Saruman goes down in the book, it’s to three child-sized hobbits and his Saruman’s spirit is a little white puff of smoke, while Sauron’s spirit emerges as a thundercloud crowned by lightning.

Hobbits? He should be so lucky. In reality, he makes his servant snap.

Oh, I forgot. It’s Grima who stabs him, and Grima who’s shot by the hobbits in turn. Either way, Saruman does get a bum’s end while Sauron goes out in grand fashion.

“I don’t have the book right next to me at the moment, but I remember one sentence” – I just posted it below! It is:

I forgot how vicious narrator and various character can be in LOTR.

Thanks, Mateusz!

Regarding sieges and cavalry charges, could you do a series on Siege of Vienna (movie is “The Day of the Siege: September Eleven 1683)? This siege is what Tolkien actually based Siege of Minas Tirith on, with Rohirrim cavalry charge on Pelennor being a direct parallel to Polish cavalry charge at Vienna – down to hidden approach over forrested hills (Kahlenburg / Anorien forrest).

I daren’t compare to the savant, but here’s a discussion of that campaign, if you’re interested: https://firedirectioncenter.blogspot.com/2017/11/decisive-battles-second-siege-and.html

Thanks!

So I guess my question would be: if he’s got warg cavalry why CAN’T Saruman simply mask Theoden once he forts up inside Helm’s Gate? Assuming a hasty circumvallation he can use the warg-riders to screen his blocking force from Erkenbrand as well as harass and destroy the Rohirrim infantry and he’s got an economy-of-force operation going to seal off the main enemy field force while the bulk of his army takes Edoras.

Theoden sorties in force and, yes, he’s got problems. But no worse problems than he’s got trying to take Helm’s Gate and the Hornburg through escalade; even assuming that it works he’s going to have a hell of a butcher’s bill. How much bigger risk is it if he throws the dice and counts on the caltrops (and that’s another rookie mistake – Saruman knows he’s going to be fighting a cavalry-heavy force, and yet he isn’t cranking out caltrops and archer-stakes (and archers) by the job lot? Hello..?) and “lilies” and his blocking force to keep Theoden penned in, takes Edoras by coup de main, THEN dispatches the Edoras force to either starve Theoden out or reduce Helm’s Gate?

Yes, the worry about the potential for the Witch-King showing up with a whole buttload of guys with the Lidless Eye on their kit is trouble. But the whole enterprise is troubled, and ISTM that Saruman’s “plan” isn’t really helping…

But in your scenario, wouldn’t the warg-riders have to chase down and eat fleeing peasants to feed their mounts? Saruman’s forces have no forward base or supply line of fresh meat for the wargs that we know of, and they’d have to disperse or hunt for food on their own, or friendly infantry and the riders themselves would be eaten by starving wargs.

Have you looked at Karen Wynn Fonstad’s Atlas of Middle Earth? She has maps of troop movements similar to these for all of the conflicts in the books and detailed assessments of travel time and movement. I was reminded of it reading through this great post.

Paul Erdkamp has helpfully uploaded all but chapter 8 of “Hunger and the Sword” on academia.edu: https://vub.academia.edu/PaulErdkamp/Books for anyone whose library doesn’t have a copy

Superb analysis, as always.

The extended edition of the movies came with tons of making-of material, which I watched in its entirety when I was a kid with lots of free time. While much of it was concerned with the visual design of the films (props, VFX and so on) I seem to recall that there was also some discussion from the three screenwriters regarding the transition from the book material to the movie script. I’d go watch it now but due to the lockdown I don’t have access to my DVDs…

Brilliant stuff, am really enjoying these analyses, BUT I do feel you’re far too hard on Saruman’s grasp of operations here. To the contrary, his operational plan and execution are not only excellent, but would have been successful if not for

you meddling kids: 1) supernatural intervention; and 2) dumb luck.First, I don’t know why you labour the point of Saruman dispersing his forces to pillage. He clearly does not. His forces spend the 2nd of March engaging and then defeating the Rohirric force at the Fords of Isen. This isn’t clear in LOTR but in Tolkien’s notes on the battle in Unfinished Tales Saruman’s army does not rout the Rohirrim at the Fords until well into the night of the 2nd, after Saruman cleverly divides his forces to attack from both sides of the Isen. By midnight of the next day (i.e. the night of the 3rd/4th) this same army then assaults a fortress which is, by your reckoning, a bit less than 40 miles away. That means that Saruman’s army marches 40 miles in less than a 24 hour period. As you know there’s no way that an army could disperse, re-concentrate, march 40 miles and then assault a fortress in that time. Logically, there could not have been any dispersal. Furthermore, the text tells us that Saruman’s army is marching directly at HD:

A host was hurrying towards HD. There was no dispersal. Rather, there was a clear prioritisation of taking HD immediately.

Second, we know that HD was a clear operational target because Saruman’s force are equipped with ladders, grappling hooks and “blasting fires”, the latter of which prove decisive in breaching the Deeping Wall. So not only had Saruman prioritised taking HD, but he had prepared his forces logistically to make an immediate assault.

Third, it’s implied in the text that HD would have been taken by Saruman’s forces if not for the intervention of the Ents/Huorns and Gandalf & Erkenbrand’s marshalling of scattered Rohirrim. The Ents/Huorns are most definitely a supernatural deus ex arboria and could not have been foreseen in Saruman’s operational plan. More practically, even Gandalf’s ability to gather up Erkenbrand’s scattered forces also relies upon the supernatural and extraordinary good luck. The sun is setting on the 3rd when Gandalf takes off on Shadowfax, effectively teleporting around dozens of squares of miles of territory gathering forces IN THE DARK and then marching them through the night to HD to attack at dawn.

Fourth, Saruman only faces material opposition at HD because Theoden has managed to get there in time, only a few hours before Saruman’s host. As you point out, Theoden’s cavalry force marches 100 miles in a day and a half to get to HD before Saruman’s army. That’s possible, but extraordinary, and only enabled by Gandalf & Co. arriving literally just before it was too late at Edoras.