This is the second part of a three part (I, II, III) look at some of the practical concerns of managing pre-industrial logistics. In our last post we outlined the members of our ‘campaign community,’ including soldiers but also non-combatants and animals (both war- and draft-); they required massive amounts of supplies, particularly food but also fodder (for animals), firewood (for heating and cooking) and water. That in turn brought us to the ‘tyranny of the wagon equation’ – without modern industrial transport (initially railroads), a pre-industrial army cannot meet these supply needs the way a modern army might, through supply lines reaching back to operational bases in the rear and from there to the productive heartland of the army itself. Instead, because everything available that can readily move food also eats food, armies are forced to gather food and other supplies locally. Because the army can only carry a couple of weeks of supplies with it, gathering new supplies becomes a continual task, a necessary concern that drives the general’s decisions.

And we’ve discussed, in rules of thumb and ‘limits of the plausible’ these sorts of concerns before. Doing so is common enough in military history literature; we use phrases like ‘foraged’ or ‘living off the land’ to describe an army’s supply actions, without ever really explaining what that means in practice. It is far rarer to discuss what the tasks involved actually look like, what the impact to the local populace might be and how an army might handle the foraged supplies. That’s what we’re going to do this week.

This is a long post (as you no doubt can already tell), but we’re going to move through the topic in four stages. First we’re going to talk about exactly the supplies an army needs need and how it can get them (mostly just to narrow down to the things an army actually forages for), then we’re going to look at ways of supplying an army on the move in friendly territory, then foraging in enemy territory and then finally examine foraging from the perspective of the foraged.

I should also note I am going to use a few chronological markers here and I want to be clear what I mean by them. ‘Antiquity’ really means the period from the emergence of writing (c. 3000 BC) to the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West (c. 450 AD), but in practice the evidence for logistical practices really confines ‘ancient logistics’ as we know it to the period from the First Greco-Persian War (492) onward. After that the Middle Ages stretch from c. 450 to c. 1450 AD, after which is the early modern period running from c. 1450 to 1789. And I should note my focus here is on the broader Mediterranean in general and Europe in particular because that’s where I know the most; different baseline agricultural products (e.g. rice or maize instead of wheat) change many of these concerns in complicated ways though none of them obviate the tyranny of the wagon equation and thus foraging (or sharp limits on operational range) remains a factor for agrarian armies pretty much everywhere.

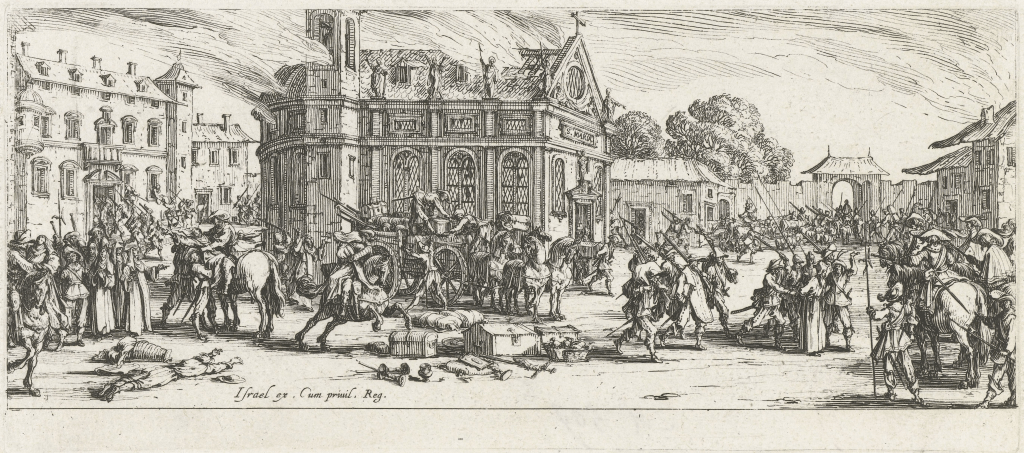

And before we head forward with that a content warning: foraging operations often involved a lot of violence directed against civilians, including sexual violence. This was a sadly common part of foraging operations which is often omitted from dry military accounts of pre-industrial campaigns, but which we will not omit here. I am also showing some period artwork which depicts violence and implies sexual violence because, again, this was a real part of historical warfare and thus a real part of history done properly. That said, reader discretion is advised and no one, least of all me, will think less of anyone who wants to skip this one.

And as always, if you want to support my logistics, you can do so via Patreon. If you want updates whenever a new post appears, you can click below for email updates or follow me on twitter (@BretDevereaux) for updates as to new posts as well as my occasional ancient history, foreign policy or military history musings.

Supplies

We should start with the sort of supplies our army is going to need. The Romans neatly divided these into four categories: food, fodder, firewood and water each with its own gathering activities (called by the Romans frumentatio, pabulatio, lignatio and aquatio respectively; on this note Roth op. cit. 118-140), though gathering food and fodder would be combined whenever possible. That’s a handy division and also a good reflection of the supply needs of armies well into the gunpowder era.1 We can start with the three relatively more simple supplies, all of which were daily concerns but also tended to be generally abundant in areas that armies were.

For most armies in most conditions, water was available in sufficient quantities along the direction of march via naturally occurring bodies of water (springs, rivers, creeks, etc.). Water could still be an important consideration even where there was enough to march through, particularly in determining the best spot for a camp or in denying an enemy access to local water supplies (such as, famously at the Battle of Hattin (1187)). And detailing parties of soldiers to replenish water supplies was a standard background activity of warfare; the Romans called this process aquatio and soldiers so detailed were aquatores (not a permanent job, to be clear, just regular soldiers for the moment sent to get water), though generally an army could simply refill its canteens as it passed naturally occurring watercourses. Well organized armies could also dig wells or use cisterns to pre-position water supplies, but this was rarely done because it was tremendously labor intensive; an army demanded so much water that many wells would be necessary to allow the army to water itself rapidly enough (the issue is throughput, not well capacity – you can only lift so many buckets of so much water in an hour in a single well).2 For the most part armies confined their movements to areas where water was naturally available, managing, at most, short hops through areas where it was scarce. If there was no readily available water in an area, agrarian armies simply couldn’t go there most of the time.

Like water, firewood was typically a daily concern. In the Roman army this meant parties of firewood forages (lignatores) were sent out regularly to whatever local timber was available. Fortunately, local firewood tended to be available in most areas because of the way the agrarian economy shaped the countryside, with stretches of forest separating settlements or tended trees for firewood near towns. Since an army isn’t trying to engage in sustainable arboriculture, it doesn’t usually need to worry about depleting local wood stocks. Moreover, for our pre-industrial army, they needn’t be picky about the timber for firewood (as opposed to timber for construction). Like water gathering, collecting firewood tends to crop up in our sources when conditions make it unusually difficult – such as if an army is forced to remain in one place (often for a siege) and consequently depletes the local supply (e.g. Liv. 36.22.10) or when the presence of enemies made getting firewood difficult without using escorts or larger parties (e.g. Ps.-Caes. BAfr. 10). Sieges could be especially tricky in this regard because they add a lot of additional timber demand for building siege engines and works; smart defenders might intentionally try to remove local timber or wood structures to deny an approaching army as part of a scorched earth strategy (e.g. Antioch in 1097). That said apart from sieges firewood availability, like water availability is mostly a question of where an army can go; generals simply avoid long stays in areas where gathering firewood would be impossible.

Then comes fodder for the animals. An army’s animals needed a mix of both green fodder (grass, hay) and dry fodder (barley, oats). Animals could meet their green fodder requirements by grazing at the cost of losing marching time, or the army could collect green fodder as it foraged for food and dry fodder. As you may recall, cut grain stalks can be used as green fodder and so even an army that cannot process grains in the fields can still quite easily use them to feed the animals, alongside barley and oats pillaged from farm storehouses. The Romans seem to have preferred gathering their fodder from the fields rather than requisitioning it from farmers directly (Caes. BG 7.14.4) but would do either in a pinch. What is clear is that much like gathering water or firewood this was a regular task a commander had to allot and also that it often had to be done under guard to secure against attacks from enemies (thus you need one group of soldiers foraging and another group in fighting trim ready to drive off an attack). Fodder could also be stockpiled when needed, which was normally for siege operations where an army’s vast stock of animals might deplete local grass stocks while the army remained encamped there. Crucially, unlike water and firewood, both forms of fodder were seasonal: green fodder came in with the grasses in early spring and dry fodder consists of agricultural products typically harvested in mid-summer (barley) or late spring (oats).

All of which at last brings us to the food, by which we mostly mean grains. Sources discussing army foraging tend to be heavily focused on food and we’ll quickly see why: it was the most difficult and complex part of foraging operations in most of the conditions an agrarian army would operate. The first factor that is going to shape foraging operations is grain processing. As noted last time, staple grains (especially wheat, barley and later rye) make up the vast bulk of the calories an army (and it attendant non-combatants) are eating on the march. But, as we’ve discussed in more detail already, grains don’t grow ‘ready to eat’ and require various stages of processing to render them edible. An army’s foraging strategy is going to be heavily impacted by just how much of that processing they are prepared to do internally.

This is one area where the Roman army does appear to have been quite unusual: Roman armies could and regularly did conduct the entire grain processing chain internally. This was relatively rare and required both a lot of coordination and a lot of materiel in the form of tools for each stage of processing. As a brief refresher, grains once ripe first have to be reaped (cut down from the stalks), then threshed (the stalks are beaten to shake out the seeds) and winnowed (the removal of non-edible portions), then potentially hulled (removing the inedible hull of the seed), then milled (ground into a powder, called flour, usually by the grinding actions of large stones), then at last baked into bread or a biscuit or what have you.

It is possible to roast unmilled grain seeds or to boil either those seeds or flour in water to make porridge in order to make them edible, but turning grain into bread (or biscuits or crackers) has significant nutritional advantages (it breaks down some of the plant compounds that human stomachs struggle to digest) and also renders the food a lot tastier, which is good for morale. Consequently, while armies will roast grains or just make lots of porridge in extremis, they want to be securing a consistent supply of bread. The result is that ideally an army wants to be foraging for grain products at a stage where it can manage most or all of the remaining steps to turn those grains into food, ideally into bread.

As mentioned, the Romans could manage the entire processing chain themselves. Roman soldiers had sickles (falces) as part of their standard equipment (Liv. 42.64.2; Josephus BJ 3.95) and so could be deployed directly into the fields (Caes. BG 4.32; Liv. 31.2.8, 34.26.8) to reap the grain themselves. It would then be transported into the fortified camp the Romans built every time the army stopped for the night and threshed by Roman soldiers in the safety of the camp (App. Mac. 27; Liv. 42.64.2) with tools that, again, were a standard part of Roman equipment. Roman soldiers were then issued threshed grains as part of their rations, which they milled themselves (or made into a porridge called puls) using ‘handmills.’ These were not small devices, but roughly 27kg (59.5lbs) hand-turned mills (Marcus Junkelmann reconstructed them quite ably); we generally assume that they were probably carried on the mules on the march, one for each contubernium (tent-group of 6-8; cf. Plut. Ant. 45.4). Getting soldiers to do their own milling was a feat of discipline – this is tough work to do by hand and milling a daily ration would take one of the soldiers of the group around two hours. Roman soldiers then baked their bread either in their own campfires (Hdn 4.7.4-6; Dio Cass. 62.5.5) though generals also sometimes prepared food supplies in advance of operations via what seem to be central bakeries. This level of centralization was part and parcel of the unusual sophistication of Roman logistics; it enabled a greater degree of flexibility for Roman armies.

Greek hoplite armies do not seem generally to have been able to reap, thresh or mill grain on the march (on this see J.W. Lee, op. cit.; there’s also a fantastic chapter on the organization of Greek military food supply by Matthew Sears forthcoming in a Brill Companion volume one of these years – don’t worry, when it appears, you will know!). Xenophon’s Ten Thousand are thus frequently forced to resort to making porridge or roast grains when they cannot forage supplies of already-milled-flour; they try hard to negotiate for markets on their route of march so they can just buy food. Famously the Spartan army, despoiling ripe Athenian fields runs out of supplies (Thuc. 2.23); it’s not clear what sort of supplies were lacking but food and fodder seems the obvious choice, suggesting that the Spartans could at best only incompletely utilize the Athenian grain. All of which contributed to the limited operational endurance of hoplite armies in the absence of friendly communities providing supplies.

Macedonian armies were in rather better shape. Alexander’s soldiers seem to have had handmills (note on this Engels, op. cit.) which already provides a huge advantage over earlier Greek armies. Grain is generally (as noted in our series on it) stored and transported after threshing and winnowing but before milling because this is the form in which has the best balance of longevity and compactness. That means that granaries and storehouses are mostly going to contain threshed and winnowed grains, not flour (nor freshly reaped stalks). An army which can mill can thus plunder central points of food storage and then transport all of that food as grain which is more portable and keeps better than flour or bread.

Early modern armies varied quite a lot in their logistical capabilities. There is a fair bit of evidence for cooking in the camp being done by the women of the campaign community in some armies, but also centralized kitchen messes for each company (Lynn op. cit. 124-126); the role of camp women in food production declines as a product of time but there is also evidence for soldiers being assigned to cooking duties in the 1600s. On the other hand, in the Army of Flanders3 seems to have relied primarily on external merchants (so sutlers, but also larger scale contractors) to supply the pan de munición ration-bread that the army needed, essentially contracting out the core of the food system. Parker (op. cit. 137) notes the Army of Flanders receiving some 39,000 loaves of bread per day from its contractors on average between April 1678 and February of 1679.

That created all sorts of problems. For one, the quality of the pan de munición was highly variable. Unlike soldiers cooking for themselves or their mess-mates, contractors had every incentive to cut corners and did so. Moreover, much of this contracting was done on credit and when Spanish royal credit failed (as it did in 1557, 1560, 1575, 1596, 1607, 1627, 1647 and 1653, Parker op. cit. 125-7) that could disrupt the entire supply system as contractors suddenly found the debts the crown had run up with them ‘restructured’ (via a ‘Decree of Bankruptcy’) to the benefit of Spain. And of course that might well lead to thousands of angry, hungry, unpaid men with weapons and military training which in turn led to disasters like the Sack of Antwerp (1576), because without those contractors the army could not handle its logistical needs on its own. It’s also hard not to conclude that this structure increased the overall cost of the Army of Flanders (which was astronomical) because it could never ‘make the war feed itself’ in the words of Cato the Elder (Liv 34.9.12; note that it was rare even for the Romans for a war to ‘feed itself’ entirely through forage, but one could at least defray some costs to the enemy during offensive operations). That said this contractor supplied bread also did not free the Army of Flanders from the need to forage (or even pillage) because – as noted last time – their rations were quite low, leading soldiers to ‘offset’ their low rations with purchase (often using money gained through pillage) or foraging.

Of course added to this are all sorts of food-stuffs that aren’t grain: meat, fruits, vegetables, cheeses, etc. Fortunately an army needs a lot less of these because grains make up the bulk of the calories eaten and even more fortunately these require less processing to be edible. But we should still note their importance because even an army with a secure stockpile of grain may want to forage the surrounding area to get supplies of more perishable foodstuffs to increase food variety and fill in the nutritional gaps of a pure-grain diet. The good news for our army is that the places they are likely to find food (small towns and rural villages) are also likely to be sources of these supplementary foods. By and large that is going to mean that armies on the march measure their supplies and their foraging in grain and then supplement that grain with whatever else they happen to have obtained in the process of getting that grain. Armies in peacetime or permanent bases may have a standard diet, but a wartime army on the march must make do with whatever is available locally.

So that’s what we need: water, fodder, firewood and food; the latter mostly grains with some supplements, but the grain itself probably needs to be in at least a partially processed form (threshed and sometimes also milled), in order to be useful to our army. And we need a lot of all of these things: tons daily. But – and this is important – notice how all of the goods we need (water, firewood, fodder, food) are things that agrarian small farmers also need. This is the crucial advantage of pre-industrial logistics; unlike a modern army which needs lots of things not normally produced or stockpiled by a civilian economy in quantity (artillery shells, high explosives, aviation fuel, etc.), everything our army needs is a staple product or resource of the agricultural economy.

Finally we need to note in addition to this that while we generally speak of ‘forage’ for supplies and ‘pillage’ or ‘plunder’ for armies making off with other valuables, these were almost always connected activities. Soldiers that were foraging would also look for valuables to pillage: someone stealing the bread a family needs to live is not going to think twice about also nicking their dinnerware. Sadly we must also note that very frequently the valuables that soldiers looted were people, either to be sold into slavery, held for ransom, pressed into work for the army, or – and as I said we’re going to be frank about this – abducted for the purpose of sexual assault (or some combination of the above).

And so a rural countryside, populated by farms and farmers is in essence a vast field of resources for an army. How they get them is going to depend on both the army’s organization and capabilities and the status of the local communities.

On Friendly Ground

Being on territory where the administrative apparatus is the army’s own or friendly to them can vastly simplify the logistics problems of moving through the territory. And we want to keep in mind throughout all of this that the army does not want to be stationary, it is trying to go places. Ideally, the army is attempting to move out of territory we control and into territory the enemy controls, or at least move away from our main administrative centers (cities, castles) to meet an approaching enemy army and by defeating it prohibit a siege. So our concern is not merely victualing4 our force but doing so while it is moving in a way that facilitates its rapid movement.

But first, we need to talk about the lay of the land. As we’ve discussed, the pre-industrial countryside is not just a uniform blanket of farms; instead settlements are ‘nucleated’ – farms cluster in villages and villages ‘orbit’ (in a sense) towns (which may ‘orbit’ yet larger towns), which usually administer those villages. The road and path system that the locals themselves have created will in turn connect fields to village centers, one village to the next and all of the villages to the town. This makes everything easier on our army which is also using those roads and paths to move – even if the paths are rudimentary, without modern location-finding data, armies use paths and settlements to know where they are. The main body of the army, with its large train of wagons, supplies and troops is going to generally move along major roads (which typically connect towns with other towns) but smaller detachments can move along the pathways between smaller settlements. That means what we have access to is not a vast field of possible maneuver but a spider’s web of pathways which meet and cross at settlements.

Moving through this pathway network, in friendly territory the army can lean on the likely compliance of the local population and the local administrative apparatus, which makes everything easier. Moreover, with control of the area, the army can send out messengers and riders who move faster than the army on its direction of march, making arrangements in advance for what the army needs, drawing supplies from the populace and (maybe) making arrangements to pay them either at the time or in the future. Doing so in hostile territory is much trickier as those messengers would be vulnerable and might reveal the army’s location and direction of march, things it might really rather want to conceal. So assuming the populace and local administration are ‘friendly,’ how do we manage the complexity of getting the food and other supplies they have into the hands of the army?

The simplest method was some form of ‘billeting,’ in use in various forms through antiquity to the early modern , though it seems particularly prominent in the Middle Ages and the first two centuries of the early modern period. Clifford Rogers (Soldiers’ Lives through History: The Middle Ages (2007), 76-78) provides a good ‘standard practices’ overview of the process for a medieval European army. Once drawn up the army was organized into smaller units (often called ‘banners’ because they marched behind a banner); we’ll come back to this again when we talk about marching speeds but it also matters here. Each banner would assign one of its horsemen as a ‘harbinger’ who would ride ahead of the army (supervised by the king or commander’s marshals), ideally a full day ahead. These harbingers (because there might be quite a few of these fellows) also acted as a limited cavalry screen. They would both designate where the army would camp next (with the marshals marking out specific encampments) and make arrangements for food and housing.

In practice ‘arrangements’ here meant frequently that the soldiers, when they arrived the following day were quartered in the homes of the local civilians, often densely packed into small towns or farming villages. If they had the means the locals might try to provide the army a market to buy food and supplies; more often the locals who had soldiers quartered on them were often expected to feed and resupply those soldiers. Notionally this was often supposed the be compensated and notionally kings issued dire warnings against soldiers taking more than they were allowed or abusing the locals. Rogers (op. cit.) is, I think, unusually sanguine in assuming these repeated regulations meant the knights and soldiers were often restrained; in an early modern or Roman context we tend to view the same sort of repeated promulgation of the same laws to mean that abuses were common despite repeated efforts by the central government to stamp them out. In practice reimbursements seem to have often been at best incomplete, where they happened at all and abuses were common.

Certainly as we see these practices more clearly in the early modern period, having soldiers quartered on your village could be economically devastating (see Parker, op. cit. 79-81); having to feed a half-dozen soldiers for a few days plus marching provisions could easily tip a small peasant household into shortage. And we should also be pretty clear-eyed here about what it would mean for a local population to have a large body of armed men (many in the hot-headed years of their youth) functionally turned loose on an unarmed civilian population and told that they could demand to be given whatever they needed; far more disciplined and better controlled armies still left a trail of theft and rape behind them as they moved. Nevertheless, this solution was simple and so for armies with very limited administrative capacity and rulers anxious to shift the burden of military activity away from their own coffers, billeting remained an attractive solution. It was still common enough in the 1700s to have been a major complaint by British colonists in North America, the bulk of whom upon achieving their independence promptly wrote an amendment in their constitution effectively banning the practice (the third amendment for the curious).

A better option for a town or city was instead to establish a market outside the town and arrange for the army to resupply and camp there and not in the town itself, with only small groups of soldiers permitted inside the walls at any given time. Needless to say, it is typically only fortified towns that really have the bargaining power to pull this off. The provision of a market for the gathering mass of crusaders outside of Constantinople in 1097 was a key diplomatic sticking point, with Alexios Komnenos I (the Byzantine Emperor) using his control over both the market and passage over the straits to Asia Minor as bargaining chips to get concessions out of the Crusaders.5 Likewise towns in Roman provinces seem to have fairly regularly paid exorbitant sums to avoid having armies quartered on them, as Cicero documents in his time in Cilicia (e.g. Cic. Ad Att. 5.21), sometimes in cash and other times in kind (e.g. Plut. Luc. 29.8). It speaks to how destructive billeted soldiers could be that towns that could went to extraordinary lengths to keep even friendly armies outside of the town walls.

Armies might also rely on local contractors to provide supplies, especially if they were going to operate in the region at some length. We’ve already mentioned the Army of Flander’s pan de munición, provided by contractors. There’s also some evidence for the use of private contractors in supporting Roman armies, though the trend in current scholarship (particularly Erdkamp but also Roth op. cit.) has tended to stress the limited and often marginal role of such contractors. Given the evidence I think Erdkamp has it right here; contractors for supplies existed in the Roman world, but were fairly small supplements to a system (detailed below) that mostly ran on taxation and requisition; most of what we see in the Roman world are just normal sutlers selling luxury foods to soldiers who want to spice up their rations.

As armies grow larger and more complex in the early modern period, we see an effort to move away from destructive ‘billeting,’ often hindered by the weak administrative apparatus of the state and limited financial resources; armies won’t move into permanent barracks on the regular in Europe until the early 1700s. One solution was to take those market towns and their lodgings and turn them from an ad hoc response to a permanent network, as Spain did along the ‘Spanish Road,’ a network of routes taken by Spanish troops traveling overland from the Mediterranean coast in Savoy to the Low Countries during the Eighty Years War.

The way this worked was To avoid having their reinforcements pillage their way across their own lands or alienate key friends on the way to the Eighty Years War (1568-1648) in the Low Countries, the Spanish government established a standard system for the supply of troops en route – key market towns were designated as étapes or ‘staples,’ standard stop-over and stockpile points. These tended to be key trade towns on the roads (indeed as I understand it étape in this sense originally meant ‘market town’) which already had some of the infrastructure required. These étapes would then be directed in advance of a movement of troops to stockpile provisions and prepare lodgings for a specific number of advancing soldiers and paid (in theory) in advance. Householders who incurred costs (typically lodgings, sometimes food) could present receipts (billets de logement) to their local tax collector which would count against future liability.

Yet the system here is incomplete and it is striking that when given the opportunity of setting up étapes in Spain itself the crown declined, citing the cost and administrative burden of organization. The greater diplomatic difficulties and consequent stronger bargaining position of communities on the Spanish Road may have a lot to do with the different decisions. The real impetus for the structure of the étapes on the Spanish road was diplomatic: the route was a patchwork, with some territories controlled by the Spanish crown, some by the friendly German Habsburgs and others by the various small statelets of the Holy Roman Empire, any of whom if sufficiently offended might refuse Spanish reinforcements transit (the Holy Roman Emperor could shut the whole route down himself). Consequently the disruption that Spanish troops caused on the route had to be limited for the route to be sustainable at all.

States with a bit more administrative capacity, on the other hand, generally tried to avoid billeting at all, even in regularized form. We’ll see this again when talking about army movement, but control is a key concern in campaigns. Soldiers, after all, are not automatons and so keeping an army together and moving towards a single objective is difficult. Soldiers get bored, wander off, decide to steal or break things (or people) and so on. It is easier to keep an eye on soldiers if they are all in a central camp or barracks and keeping an eye on everyone in turn makes it a lot easier to ensure that everyone shows up promptly to muster in the morning with the minimum of hassle. So if a general can, he really would want to keep everyone out of towns and villages and in a regular marching camp. Doing so demands yet more discipline because of course the soldiers would rather sleep in houses than in tents, but it has substantial advantages.

But an army that can lean on the local administrative capacity can simply demand that local administrative apparatus, whatever its form, coordinate the collection and transport of supplies (over short distances) to the army, enabling the army to camp out in a field and get its grain DoorDashed6 to it. Thus the Romans, when in friendly territory, for instance first identify the local government – usually a town but it could also be a tribal government in non-state regions – and then requisition food from that government, transmitting their demands in advance and letting that local administration figure out the details of getting the required food to the required place. That lets Roman armies camp in their fortified camps away from civilian centers, with attendant advantages for discipline; and indeed, Roman armies typically avoid permanent or even temporary bases in towns, instead using the threat of billeting to get the supplies they needed to stay in regular camps and later permanent forts.

Via Wikipedia, remains of one of the Roman forts used in the siege of Masada (72-3AD), still showing the distinctive playing-card shape of Roman marching and siege camps.

While the elites who run these local systems of government could provide such requisitions themselves (and might in extremis to avoid retaliation by their superiors; the Romans interpret failure to provide requested supplies as ‘rebellion’ and respond accordingly), in practice they’re going to pass along as much of the costs as they can to the little guy. In some cases, requisition demands are so intense we hear of towns having to buy or import grain to meet the demands of passing armies; Athens had to do this in 171 during the Third Macedonian War to avoid the wrath of Rome (Liv. 43.6.1-4). Caesar likewise relied heavily on food supplies contributed by either allied or recently defeated communities in Gaul (Caesar, BG 1.16, 1.23, 1.40, 1.37, 2.3, 3.7, 5.20, 6.44; he does this a lot) to supplement regular foraging operations. Those sources of supply in turn influence his campaigning, as Caesar is forced to move where the grain is in order to resupply (e.g. Caes. BG 1.23). And I want to be clear even these systems of requisition could mean real hardship on a population as a large army could easily eat all of the surplus grain in a province and then some.

The exact structure of that requisition could vary; in some cases it was a extraordinary tax (which is to say, it was just seized), but in many cases it was organized as a forced sale (often at below market prices) or even rebated against future tax obligations. In the Roman Empire we know that in many provinces, initially ad hoc systems of food requisition from conquered or ‘allied’ (read: subordinated) communities were first regularized so that the demands were set at a steady amount, then monetized as military operations moved further away, until eventually being formalized as a taxation system.7 Thus the primary Roman tax system of the imperial period grew not out of the tax system the Romans had in Italy (which was mostly dismantled in the second century as the tremendous wealth of the provinces made it unnecessary) but as a regularization of systems of requisition and extortion meant to support armies. The Romans also took advantage of the Mediterranean (where naval transport could break the tyranny of the wagon equation) to ship food from one theater to another (so long as operations were fairly close to coastal ports); this was in the Republic coordinated by the Senate which could direct Roman officials (typically governors of some sort) or non-Italian allies in one region to obtain supplies by whatever means and send them another active military theater (Plb. 1.52.5-8, Liv. 25.15.4-5, 27.3.9, 31.19.2-4, 32.27.2, 36.3-4), in some cases even establishing transit depots which could support operations in a large naval theater (e.g. Chios, Liv. 37.27.1). In particular, grain taxed in Sicily was frequently redirected to support Roman military operations across the Mediterranean.

All of this of course assumes that the army enjoys either the use of the local administrative system or the compliance of the local population. But of course in enemy territory – which is where your army wants to go – you cannot rely on that. What does the army do there?

Foraging the Enemy

This at last brings us to foraging. As noted, the goal of an army once formed up is usually to move into enemy territory either to meet an opposing army there or to deliver a siege to a fortified enemy settlement, like a castle or walled city. An army marching out of friendly territory, of course, would be wise to gather as much supplies (especially food) as possible on the way out, but once in enemy territory the tyranny of the wagon equation (and the general difficulty in guarding overlap supply lines) means the army will need to gather food locally from a populace that is at best in indifferent and likely actively hostile to the army.

The process of (usually violently) gathering food in hostile territory is referred to in a military context as ‘foraging,’ a fairly bloodless word for what could be a quite ugly process.

As we discussed in our series on farming, one of the structural problems farmers faced is that they eat every day but the harvest only comes in once a year. The obvious solution was stockpiling the results of the harvest to last through the year. As a result just before the harvest a farming village has a year’s worth of grain growing in its fields and just after the harvest a year’s worth of grain threshed, winnowed and sitting in its granaries, barns and farmhouses. That stock depletes over time (as the farmers eat it) hopefully never quite reaching zero before the next harvest comes in. The same cycle (on slightly different timing) goes for green fodder, with grasses ripening in the late spring and being most scarce in winter.

Most armies could do relatively little with grain in the fields, but by aiming to commence operations in late spring/early summer allows the army to arrive in enemy territory right as the winter wheat (the main European/Mediterranean wheat crop) has been stockpiled in the granaries having just been harvested (in early summer, the exact days vary by region). I should note that grain is not the only concern here; the availability of green fodder (read: grass) is also crucial; green fodder tends to come in somewhat earlier than grains and often marks the true beginning of the campaign season. Having readily available green fodder vastly reduces the logistics demands of horses and other work animals, making it much easier to keep the rest of the army supplied. Roman armies, for instance, were mobilized in March (Roman Martius, the month of Mars, because the Romans are not subtle) for this reason; the general rule of thumb is that the campaigning season in Europe began with the Spring Equinox in late March. But this timing means that by the time the army is mustered and moving into enemy territory, the harvest is close.

Meanwhile recall that the farms are not scattered randomly; they are clustered into small settlements, which connect to each other and larger settlements by roads and paths. Each small settlement (villages, hamlets, monasteries (in the post-antique); for simplicity’s sake I’m just going to say ‘village’) is essentially a food piñata for the army: full of food but some violence required for extraction. Thus as an army advanced it could break off smaller units to take side roads and paths to the villages of the countryside. The villagers generally would be no military obstacle: outnumbered, untrained, unarmed and often unaware there was an army coming (remember, this is a world where the fastest moving information is ‘man on horse’ so a foraging party could often outrace news of its coming) they had few options for direct resistance. The foraging party could then demand the villagers turn over their produce or, more often (since villagers tended to flee foraging parties and for good reason as we’ll see) simply break into houses, granaries and barns to seize it. They could also seize and lead off farm animals for meat. Thus the army could be supplied off of the produce of the enemy (or at least, the enemy’s poor rural population).

Now I said ‘smaller units’ but we should be clear here, ‘foraging parties’ tend to actually be quite large. The concern isn’t the villagers; a normal village typically has only around 5-20 households (so a few hundred people, roughly half of them adults) and isn’t configured for defense anyway.8 But you are in enemy territory and so while part of the party forages another part – large enough to defend itself from a significant enemy force – needs to be keeping guard. Rogers’ (op. cit., 77-8) notes that foraging parties could represent up to a third of a medieval European army’s total army’s strength, typically split between fast-moving outriders who surprised settlements and slower moving foragers who then caught up to loot them. The Rule of the Knights Templar, which included campaign regulations, specified that knights could not send out members of their retinue to forage or even fetch wood without permissions (Verbruggen, The Art of Warfare in Western Europe During the Middle Ages (1997), 78), essentially banning small-scale foraging in favor of larger parties. At Antioch in the winter of 1097/8, a crusader foraging party under the command of Bohemond of Taranto and Robert of Flanders slammed into an entire relief army under the command of Duqaq of Damascus and defeated it; the size of both forces is unclear but they were evidently not small. The standard Roman foraging party seems to have been an entire legion (remember that a Roman army is typically several legions; this would have been a quarter of a normal Roman field army) so roughly 5,000 men (e.g. Caes. BG 4.32; Plut. Luc. 17, Sert. 13.6; App. BCiv 4.122) though detachments for smaller armies could be smaller and larger foraging parties were sent out when enemies were considered close. I’ve had a harder time getting a sense of the standard foraging party for a early modern army but generally the units seem to either be hundreds or low thousands (which is to say anywhere from a company to something like a full tercio or regiment); part of the irregularity is that early modern units were rarely anywhere even close to their ‘paper’ strength.

To give a sense of the process over a large area, the Chanson des Lorrains (early 13th century, via Rogers, op. cit. 87) describes one such medieval army foraging its way through the countryside:

The march begins. Out in front are the scouts and incendiaries. After them come the foragers whose job it is to collect the spoils and carry them to the great baggage train. Soon all is tumult. The peasants, having just come out in the fields, turn back, uttering loud cries. The shepherds gather their flocks and drive them towards the neighboring woods in hope of saving them…the terrified inhabitants are either burned or led away with their hands tied to be held for ransom…money, cattle, mules and sheep are all seized. The smoke billows and spreads, flames crackle. Peasants and shepherds scatter in all directions.

Here the division is clear, with the armed ‘scouts and incendiaries’ moving first, dispersing (or capturing) the villagers and securing the area, with foragers (usually armed but in some cases these are non-combatants or momentarily unarmed combatants) coming up behind to actually grab the stuff. While the key thing here is the acquisition of supplies in practice under these conditions soldiers grab anything of value they can find. I should note with this quote that while foraging and agricultural devastation could be separate tasks, here they are joined (which was also very common): the army both loots and burns. Armies could forage with or without the intent to devastate (though foraging imposed its own costs) and could devastate with or without the intent to forage (foraging being more time consuming than just burning everything and moving on). Also note they are burning the houses and barns, not the grain; ripe grain doesn’t actually burn all that well under most conditions.

The non-combatants of the army were also likely to be a part of the foraging party, participating in both the ransacking of settlements and of course the carrying off of loot and supplies. Roman camp servants (generally enslaved persons), the calones we mentioned last time seem regularly to have been part of foraging parties and we know that they were at least sometimes armed. It is hard to see non-combatants in medieval sources but a knight’s retinue would include both lower-class combatants and servants; in some cases ‘forager’ was a specific position in such a retinue (Rogers, op. cit. 28) but we have to imagine in many cases servants whose job was ‘carry stuff’ would, of course be employed carrying looted supplies too. In early modern armies it is very clear that camp women were a regular part of foraging parties, connected to the role they had in managing the camp’s cooking and logistics. Early modern artwork showing scenes of forage or pillage regularly features camp women (see below) and sources repeatedly mention camp women involved in what Lynn (op. cit.) terms the ‘pillage economy’ as a joint venture with their husbands or other menfolk. It speaks to the normalization of this part of warfare that despite how stunningly violent foraging could be (as we’ll get to), common soldiers in early modern armies do not seem to have thought twice about bringing their wives along.

In terms of targets the Romans do stand out a bit; Roman foraging parties absolutely raided farms and storehouses, but Roman soldiers also carried sickles (falces) as part of their standard equipment (Liv. 42.64.2; Josephus BJ 3.95) and would not only mow their own green fodder but actually harvest grain directly from the fields of an enemy (Caes. BG 4.32; Liv. 31.2.8, 34.26.8). You can actually see Roman soldiers doing this on Trajan’s Column (below). Grain once reaped was transported back to the camp to be threshed in relative safety (Liv. 42.64.2; App. Mac. 27), presumably to avoid having the foraging party out in the open any longer than necessary. Roman soldiers, drawn from a large class of freeholding farmers, would have already had the necessary skills and a large foraging party could clear fields very quickly, essentially ‘cashing in’ on months of the farmer’s labor in just a few hours of reaping. As far as I can tell, this capability was unusual and seems to have facilitated a considerable degree of Roman logistical flexibility, especially with infantry-based foraging parties; peasants can potentially flee with or hide harvested grains, but they cannot hide their fields.

Now the peasantry in these situations cannot really fight back, but that doesn’t mean they have no options at all. Unlike the approaching army, the peasants know the local landscape and (if given enough warning) can easily vanish into it (like those shepherds vanishing into the forest). As Landers puts it, “armed men could usually rely on violence or the threat of it to take what they wanted, but they had to find it first” (op. cit. 215). Peasants were canny survivors who knew how to, for instance, quickly hide valuables or food or grab what they could and flee. A significant portion of their grain was kept back, for instance, as seed grain to plant for the following year; it didn’t need to be eaten and so the smart peasant might intentionally hide it if he thought there was risk of being foraged. A foraging army could try to defeat this resistance through terror: burning the farms of farmers who fled or holding captured farmers hostage against their hidden food and valuables. The value of getting to the peasants with enough speed to capture them before the melted away into the countryside made cavalry particularly valuable for an army foraging. Horsemen, moving fast could reach the village before they knew the attack was coming, preventing peasants from hiding grain or fleeing (so they could be forced to divulge the location of supplies or ransomed). At the same time, political authorities who suspected their region might come under attack may give orders to move all of the surplus food into the fortified settlements, dramatically reducing the forage available in the countryside.

How much food might be available in the best case? Well a fairly typical village might have a couple hundred people in it (something like a dozen households; peasant households tend to be large). Their grain for the whole year (so 365 days worth of grain) is going to be gathered in just a few weeks at the harvest in early summer or late spring. So a village, for instance, of around 200 people is going to have something like 70,000 man-days of grain on hand (plus or minus; some of those people don’t eat as much as an adult male soldier, but then there is also some surplus grain, feed for animals and other non-grain foodstuffs). If you could get all of that food (which the peasants are trying to prevent), you could fill the packs of an army of 10,000 to march for another week. Of course actual rural settlement is going vary a lot more than this (larger villages, smaller hamlets, small unwalled towns bigger than both, the occasional isolated homestead).

Now that ideal will rarely be achieved, especially over a large area. Military rules of thumb typically approach foraging from the standpoint of how much population density Y is required to support X number of troops under campaign conditions. But I want to ask the question a different way: an army with an active cavalry detachment could potentially forage a front around 20 miles wide (infantry might be half this). If the army moves at ten miles per day, that’s 200 square miles of terrain, which at agrarian, pre-industrial densities might have 5,000 people in it (25ish people per square mile; densities can be substantially higher than this but often wasn’t), so right after the harvest they’d have about 1.35 million people-days of food,9 which conveniently for us, we can say is roughly a kilogram of food (mostly grain) for each person-day. Recall our sample army from last time of 19,200 combat effectives (but also 4,000 non-combatants and 9,800 animals) needs around 61,850kg of food (including hard fodder but not green fodder) per day or about 5% of the total to survive.

The exact structure of foraging operations varies from one army to the next as well. Clifford Rogers describes a medieval army as “a solid mass of baggage and troops in formation, a loose perimeter of outriders miles out from the center, and in between a large cloud of men dispersed to conduct the heavily overlapping tasks of burning, plundering, ravaging and foraging” (Rogers, op. cit., 86). By contrast the Romans, whose process I am most familiar, clearly did not generally do this but rather sent out large foraging parties at regular intervals (connected, doubtless, to the army having standard days for the distribution of grain; Caes. BG 4.32.1, 6.36.2, BAfr 65; Plut. Sert 13.6); those large foraging parties would then ‘stock up’ the army’s camp, providing enough supplies for several more days of marching. That said having foragers out slowed down an army; foraging intensively slowed it down more. After all, if the main body of the army is moving around 8-12 miles per day, even mounted outriders that have to ride out from the army to outlying villages will only have a few hours at their ‘targets’ before they must ride back.

Consequently an army that wanted to move quickly would accept that it was going to miss quite a lot of the available forage in an area, either by doing a continuous but not very intensive ‘initial pass’ or by performing high intensity foraging operations only every few days. After all, the army’s ability to carry food is limited in any event. Moreover, remember that these armies often lack detailed maps and so many small settlements may escape being plundered by simply being missed; others by seeing smoke or other signs of an army with time to grab everything of value and hide or flee. Being careful and methodical could mean getting more food out of the countryside, but it would also be slower and our army does not want to slow down.

That means foraging does not hit every village in a region evenly: some villages may be extensively searched, with all of the hidden seed grain and valuables found, others may be given a quick once-over with just the storehouse looted, while others will be missed entirely. Our sample 200 square miles of daily foraging reach might have something like two dozen villages in it of varying sizes. Even within an area actively foraged, many small villages or more isolated homesteads might be simply missed by an army that doesn’t know the area very well. Combined with peasants trying to flee and survive, that drastically limits how much food the army can actually pull in within a foraging ‘zone’ perhaps 200 miles wide along its marching route; the rule of thumb estimates usually suggest an army can only actually pull in 5-15% of the available food in an area while still moving; doing more than this requires slowing down and also begins to depopulate the area which in turn creates logistical ‘dead zones.’ Large foraging parties in turn work because while the army is only extracting a small amount of the total food in the 200-mile wide radius around it, it is extracting a very large amount of the food in the specific villages it hits such that just a few villages thoroughly looted can supply an army for another set of marching days.10

Of course the season also matters here. So far we’ve been assuming the army hits a village more or less in June or July, immediately following the harvest. But as the months go by the amount of grain in those village storehouses is going to dwindle as it is eaten by the peasantry, meaning that the potential gains from foraging peak after the harvest and then decline over the year. A general planning the logistics of his army needs to be thinking about how he will feed his soldiers not just in June but also in October and potentially even in January or February. As noted by late fall the amount of food available in the countryside has declined by half; our sample 20,000 man army suddenly goes from being at a comfortable 5% of available forage (at that 25 per square mile density) to a far less comfortable 10% (at which point it would become pressingly necessary to keep moving to avoid exhausting local supplies). The campaign season (beginning in late March or early April) is thus neatly timed so that the army’s initial stockpiled supplies from friendly territory can carry it until the early summer harvest when forage suddenly becomes plentiful. But the risk then lay at the beginning of winter as forage started to dwindle again. One possible response was to only keep the army together during the ‘campaigning season’ and send everyone home for the winter, but having to restart the campaign every year could be a real problem if long sieges were required or if wars had to be fought at great distance.

Armies that stayed ‘in being’ over the winter tended to go into ‘winter quarters’ – a phrase that gets used in primary sources and also in a lot of campaign histories without generally being defined. The concern here is that both the bad weather of winter making campaigning hard but also the scarcity of forage would make offensive operations unsustainable, so the army ‘hunkers down’ for the winter. You can tell supplies are a key factor here because armies go into winter quarters even in regions that have very mild winters. The choice of location and its preparation were crucial. Roman armies were year-round campaigners even from a relatively early point and so the need to prepare winter quarters shows up repeatedly in the sources, with a variety of solutions to the problem of what to do with the army during winter. Commanders might, for instance, ‘winter’ their armies near controlled ports or rivers to enable resupply by sea (or by coastal depots carefully stocked up during the year) or near friendly communities which could supply them via taxation, requisition or markets. Alternately, a general might identify a particularly agriculturally rich region to ‘winter’ on, relying on the robust local supply (typically from a dense population in a rich agricultural area) to see the army through winter, often in addition to food stockpiles built up by foraging during the campaigning season (which of course have to be located in depots; as we’ve discussed the army cannot carry multiple months of food with it on the march).

Finally please note our calculations above assume that the army keeps moving continuously, but of course armies didn’t always keep moving every day. They stop to rest, or to conduct sieges; they double-back to maneuver for a favorable battlefield and so on. Our sample army of 19,200 troops and minimal non-combatants clears out 5% of the total food supply in its neighborhood per day. If the general plans to stay put for more than a few days (much less a month or two for a quick siege) he needs to keep moving and forage even more intensely in order to build up or maintain stockpiles. We’ll come back to this next time, but this is why the ‘upper limit’ of ancient, medieval and early modern field armies in the broader Mediterranean11 remains so stubborn: 20,000 is normal, 40,000 is big, 80,000 is unusually huge and more than 80,000 is unsustainable in almost all circumstances.

All of this goes to how a general is going to plan the march of an army: he needs to ensure his army moves slow enough to forage sufficient supplies but not so slow it ends up foraging the same people twice. He also needs to think about the size of his army: too big and local forage will be insufficient at any speed (and also large armies with lots of supplies are slow). And of course the route of march matters: large armies must stay in densely populated, easy to forage territory while smaller armies can subsist in areas with far fewer local farmers (and at substantially less damage to those local farmers). Our sample army of 19,200 soldiers, 4,000 non-combatants and 9,800 animals can go almost anywhere that isn’t desert in the broader Mediterranean world; double its size and it will be much more limited in where it can go (and much more damaging on the way there). It’s also not hard to see how an army loaded up with non-combatants – be they early modern camp women or medieval valets, servants and pages – can actively reduce the maneuver options of the army by raising the population density it needs (we’ll come back to this).

Impact on the Countryside

So that is foraging from the army’s perspective. What about from the peasant’s perspective? Well, from the peasant’s perspective, even a friendly army might fit somewhere between a nuisance and a disaster; an enemy army was a rolling catastrophe moving across the countryside, a plague of armed men.

In the best case a pre-industrial farming community being ‘billeted’ or ‘quartered’ on might have the main part of their costs reimbursed by the army, but this still meant hosting a large number of armed men, possibly for days. Soldiers were often ordered not to steal things or get involved (by persuasion or force) with local women but the sources also overflow with reports that such orders were frequently ignored. In the late 1600s, billeting was actually used as a tactic for domestic religious persecution , as with the French dragonnades, which permitted the billeting of troops in Protestant households to ‘encourage’ them to convert to Catholicism. And in practice reimbursements for the expenses of soldiers lodged and fed at the local’s expense were often either not forthcoming or well below market rates; Roman armies tended to stay away from civilian centers but often relied on ‘forced sales’ of supplies well below market rates with the losses absorbed by the locals. For reasons we’ve discussed, individual peasant households were generally not prepared to handle the expense (heck, how many modern households could handle the expense of feeding, housing and caring for, say, six soldiers for every bedroom in their house for a month?) and the nature of billeting meant that it tended to strike a whole community at once making it harder to ‘distribute’ the costs via horizontal relationships.

The more organized and centralized the army, the more hardship on friendly civilians could be limited, but doing so was dependent on both budget and state capacity. If soldiers could be kept in camps or barracks rather than in civilian centers, the economic and social damage to friendly rural populations could be mitigated. Roman armies were for this reason generally kept out of friendly towns; the Roman preference in the imperial period for legionary bases outside and often quite distant from major civilian centers is marked (although such bases often created towns over time). The polities of medieval Europe and the states of early modern Europe largely lacked this capacity, with centralized barracks to house armies on friendly soil in peacetime only becoming really common in the 1710s.12 Even so, quartering – especially ‘at discretion’ (that is, at the choice of officers or individual soldiers) was still common enough and enough of a hardship that the framers of the US Constitution went out of their way to ban it in the Third Amendment in 1789.13

Being the target of foraging operations was worse. Warfare before the very late 1800s recognized few if any protections for ‘enemy non-combatants’ and as a result civilians in hostile territory were subject to whatever violence soldiers might meet out.14 Because rural populations tended to be fairly isolated and communications were so slow, the earliest warning a peasant community might get that an army was coming might be fires on the horizon from other villages being burned just a few miles away (and thus perhaps only minutes or hours away); in practice most villages had practically no warning before foraging parties descended on them. Once aware, it would be a rush to grab or hide whatever moveable property could be grabbed and attempt to flee (often trying to vanish into forests, as in the quote above). Bertran de Born actually gives this spectacle as one of the things he loves in war, “And it pleases me when the skirmishers/make the people and their baggage run away,/ and it pleases me when I see behind them coming/a great mass of armed men together…;” one is left to conclude the peasantry was much less pleased but they’d have been fools to trust to the mercy of warrior-aristocrats. They ran and were wise to do so.

While the purpose of these operations was to obtain supplies, pillaging enemy non-combatants was in almost all cases considered one of the perquisites of war. Foragers would thus also be looking not merely for food but also for any valuables that could be looted. Early modern armies, with their irregular pay (as a result of state finances crumbling under the new burdens of war in the period) seem to have been particularly destructive looters and we have abundant evidence that looting was an important part of the economics of soldiering in the period; a campaign with insufficient looting opportunities could financially ruin soldiers (and their camp women who clearly aided in the looting and seem to have generally shared in the spoils). That said, this wasn’t a phenomenon tied specifically to the early modern period; it is safe to assume that ancient and medieval armies also looted enemy settlements wherever they went.15

For peasants that weren’t able to escape, capture could be a brutal (and sometimes fatal) experience. Captives were valuable; in the ancient world they become part of the loot directly, enslaved and sold to the slave-dealers that followed ancient armies (from where slavery was likely to remain their living condition for the rest of their lives) while in medieval Europe they might be ransomed back either to their families or en masse to the castle or town that governed the area (though they might also be enslaved, especially if their religion did not match that of their captors). Moreover, precisely because peasants had adapted to survive in this environment, soldiers often assumed that valuables were kept hidden; the resort to the torture of captured peasants (see above) or terror – killing some to compel others – in order to reveal hidden valuables or food stocks seems to have been a common part of foraging operations.

And we should not retreat into euphemism about female captives: captured women were very frequently raped. As Lynn (op. cit.,153-156), notes, this was so common as to have its own euphemistic artistic representations (typically a soldier grabbing a woman by her hair, an artistic symbol of capture and rape that extends back into antiquity, but sometimes more graphically soldiers forcing a woman into bed, see below). In ancient warfare, women taken as captives, like men, would have been enslaved; enslaved persons lacked a legal right of bodily autonomy and were thus frequently subject to rape. Early modern accounts regularly report women take as part of the plunder of towns and villages for the purpose of both forced labor in the army’s camp and rape.16 Medieval accounts written predominately by the clergy might be a bit more circumspect (in part due to stronger norms about violence against co-religionists), but it is evident that war rape was common in this context too. By way of example, Fulcher of Chartres, a churchman eyewitness to the First Crusade (1096-1099), stresses the virtue of the Crusaders who ‘only’ murdered captured Muslim women, instead of raping them: when the Crusaders captured women in the camp of a Muslim army after a battle outside of Antioch (1098) they “did nothing evil to them except pierce their bellies with their lances.”17 Nevertheless other Crusade accounts, like the Gesta Francorum, make abundantly clear that the Crusaders enslaved captured young women even as they massacred everyone else. There’s a reason that the farmers knew to run and hide in forests and hills; the alternatives – even in a capture-and-ransom society – were much worse.18

Even after the foraging party passed the ordeal for the peasants wasn’t necessarily over. After all the foraging party will have stolen valuables but also made off with vital agricultural capital and products: animals, tools seed and of course food. The loss of a substantial portion of the harvest could be devastating to a peasant family, forcing them into starvation in the short term, while the lost of animals could represent the destruction of years of carefully built of agricultural capital. If the army was intentionally devastating the land (a common strategy in pre-industrial warfare but not unknown to modern war as well), they might have also burned farmhouses, barns and other structures. Suddenly deprived of the basics of subsistence, farmers may have tried to use social networks to seek help or else stream towards cities and towns to find safety and work (though if food was scarce, as it might be if the countryside was being pillaged, towns were quick to shut their gates to rural folk to preserve supplies for the townspeople). Alternately they might turn to their own political authorities for aid. Failing that, they starved.

That said it seems fairly clear that while foraging operations could be utterly ruinous (and fatal) to individual farmers and communities, actually depopulating a region required repeated military operations in the area over multiple years. Peasants, after all, knew the risks of military activity and so prepared for them, cultivating those social networks, hiding seed grain and valuables, knowing where to run if an army came by and so on. The entire way of life for pre-industrial farmers was oriented around resiliency in the face of disaster, though here we also need to be careful of a form of survivorship bias: the countryside was populated entirely by survivors of events which not everyone survived. The fact that the peasantry might demographically recover could be of little comfort to the rural folks who were murdered, starved or raped.

Not all foraging operations were this brutal, though brutality does seem to have been the norm. Armies might act with more restraint if they expected the need to campaign in an area over long periods or desired to control the land (and thus would want to preserve the productive peasantry for future taxation). Consequently it was often in the interest of the general and his officers to keep foraging operations limited; to shear and not skin his sheep, as it were.19 Thus French Marshal Villars advised his soldiers when marching into enemy territory for an extended campaign, “If you burn, if you drive out the population, you will starve.”20 He knew what he was talking about – the 1600s had seen many armies burn and then starve as they destroyed the very agricultural fabric they relied upon to operate. Nevertheless actually restraining the army in the moment proved difficult, even for generals who knew they needed to be restrained, especially when the soldiers relied on forage to eat and pillage to pay their way.

More broadly the constraints of warfare also impacted its destructiveness in any given era. In particular the early modern period seems to represent something of a peak in the uncontrolled destructiveness of armies, a combination of the burgeoning size of field forces as compared to the Middle Ages with state finance and logistics systems unprepared to cope with the new larger armies. Medieval armies may not have been any nicer, but they were smaller which reduced their impact, while the armies of the 1700s and 1800s were increasingly better organized and supplied and as a result less logistically destructive. Armies in the Hellenistic and Roman periods were substantially larger than in the Middle Ages (comparable for the armies of the 1600s and 1700s in size in some cases) and could be staggeringly destructive; Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul seem to have verged on genocide even if we assume some considerable degree of exaggeration. At the same time, Macedonian and Roman generals seem (keeping in mind the limits of our sources) to have been able to restrain their armies when they wanted (regular pay helped), relying on local polities to deliver food at the threat of violence rather than uncontrollably pillaging their surrounds. Pushing back much further than this runs into severely limited evidence, though foraging as an essential part of agrarian logistics seems to be true for basically all large agrarian armies, stretching back into pre-history.

One solution commanders might lean on were variations on what in the 17th century were called ‘contributions.’ Armies moving into a region, rather than having soldiers forage directly, would instruct civil authorities – village headmen, mayors and so on – to ‘contribute’ supplies and cash at specific places and times, essentially extorting local civilian populations. It was the reinvention of an old system: Alexander the Great relied on communities he approached preemptively surrendering to him, negotiating the food they’d supply his army to get it to the other side of their territory and safely away from them.21 Similar arrangements might be made in the Middle Ages, with an army negotiating with a local enemy city or castle to agree to avoid violently pillaging the countryside if its supply needs were met (Rogers, op. cit., 87), though in many medieval campaigns the agricultural devastation was itself the goal (aimed at compelling a political outcome).

If carefully managed such arrangements could make for efficient extortion, though the demands of large armies (often several tens of thousands) could still put severe strain on communities in the area of operations. Repeated ‘contributions’ and foraging over the course of the Eighty Years War (1568-1648) in the Low Countries and the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) in the Holy Roman Empire both created depopulated ‘no man’s land’ areas which in turn made further military operations logistically challenging as no army can forage a depopulated countryside; devastation on this scale and over this much area seemed to have been mostly out of reach for the smaller armies of the Middle Ages.22 In the late 1600s, we see a marked shift towards a greater degree of central state supply and control which begins to reduce the uncontrolled destructiveness of armies (even as the intentional capacity for destruction of armies is rising), though foraging is still a major factor in warfare well into the 1800s. That said even modern armies are by no means immune to plunder or foraging, especially when other forms of logistics fail.

If this needs saying: war is terrible, we should do less of it.

All of this has substantial impacts on where a general can take a pre-railroad army and how fast it can move or how long it can remain and we’ll turn to that next time, but I want to stop this post here and keep focus on the miseries of war. Foraging and devastation operations in ‘enemy’ territory against unarmed civilian non-combatants is a part of pre-industrial warfare23 that is frequently omitted both in the popular portrayal of such warfare but also in its broader discussion by historians. We write books about how general so-and-so took his army here and then there and maybe offer some bloodless line about how they ‘ravaged the such-and-such district,’ but only rarely engage in what that means (and when we do, typically only to other scholars). In part we do that because it is what our sources do; foraging was normal and so there was no need to explain it. Or we pretend that this kind of warfare was particular to just one period, rather than being the norm of agrarian warfare in all historical periods.

But actual pre-industrial armies were brutal, destructive things by their very nature, even if our sources often obfuscate the violence they are doing in part because they do not care about the sort of ‘others’ (more often ‘others’ by social inferiority than by cultural or religious difference) who are having the violence done to them. But of course those ‘others’ are most people – the rural population on the business end of this kind of military activity make up most of the population. Every so often someone asks “If you were in [era in the past], what would you be?” and folks respond with kings and knights and clergy and artisans. But you wouldn’t, would you? By the numbers, we wouldn’t be the soldiers in gleaming armor, we’d all be the poor peasants desperately grabbing what few valuables they had and their families and sprinting in the woods as everything we had built over decades burned behind us.

That is as much, if not more, the reality of ‘How They Did It’ as the spectacle of the battles or sieges.

Next week (schedule subject to moving house) we’ll look at how all of this relates to moving an army: where it can go and how fast it can get there.

- What about gunpowder itself? Armies generally carried their powder with them. Maybe at some point we’ll talk about the black powder and how its made, but producing good powder on the march would be a challenge and doesn’t seem to have usually been a driving concern in any event, as far as I can tell.

- On this topic, see Roth, op. cit. 119-125 and in more detail G. Moss, “Watering the Roman Legion,” Master’s Thesis, UNC Chapel Hill (2015).

- ‘The Army of Flanders was a logistical disaster’ is rapidly becoming the running theme of this series and that seems, on the whole, pretty accurate.

- an actual word that means ‘to supply food to an army’ (inter alia).

- I appear to have already packed my First Crusade source book so I don’t have the citations to Fulcher and Anna Komnene handy, but I’ll try to remember to come back and add those once I’ve fully unpacked my books.

- Link simply because I do not know if DoorDash is as common in other countries and so this joke might need a gloss. I’m actually not very fond of DoorDash; the service is expensive but they don’t pay their Dashers well.

- on this see J.S. Richardson, “The Spanish Mines and the Development of Provincial Taxation in the Second Century B.C.” JRS 66 (1976)

- Though of course you might hit multiple villages in an area at the same time or in quick succession

- Reduced by 25% because soldiers nutrition requirements are substantially higher than the average peasant because, of course, many peasants are children, women or elderly people with lower calorie demands

- And that ‘get hit hard or not at all’ kind of risk is, of course, precisely the kind of risk that the vertical and horizontal social relations peasants rely on are designed to mitigate.

- Rice agriculture with its higher population densities has different breakpoints.

- For a good surface-level overview of these processes, see Lee, Waging War (2016) ch 9.

- By far the most successful of the first ten amendments. It has never been the primary subject of a Supreme Court decision – see how well it works!

- “It’s wrong to deliberately target civilians” is a fairly recent and very valuable moral innovation. I don’t want to entirely oversell this: particularly in the Middle Ages there were at least notionally some moral qualms about violence against co-religionists, but these fell far short of modern international law, even with all of its weaknesses.

- Though in all cases the most important sources of loot were towns where the greatest wealth was; that doesn’t mean armies didn’t rob the peasantry (they absolutely did) but an army that only robbed the peasantry would have sorely disappointed (and possibly impoverished) its soldiers.

- As Lynn notes, this was a process that would have been taking place in armies with large numbers of camp women in the ‘campaign community’ who were there of their own volition. Lynn concludes that the evidence suggests that on the whole that most camp women “realized what was happening and tolerated it since those attacked were “others,” and women within the campaign community shared the identity and values of that community.” There is little if any evidence that they objected and significant evidence that they often took part in the pillaging. This may also go some distance to explaining why accounts of the period – even by soldier-rapists themselves – often make little effort to conceal it; it was considered a ‘normal’ part of war against an enemy. As Lynn notes, the enmity could also go both ways: neither soldiers or camp women who found themselves alone and unprotected in a hostile countryside could expect mercy from the populace.

- Trans. from E. Peters, The First Crusade: The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres and Other Source Materials.

- I should note that even a casual survey of the literature studying modern war crimes will also reveal that this sort of behavior – while now forbidden by law in most countries and by international law – remains common, particularly in wars where the civilian population is the deliberate target. Atrocities are not simply something that only happens in the past.

- Suet. Tiberius 32.2, though on taxation rather than foraging.

- Quote via F. Tallett, War and Society in Early Modern Europe: 1495-1715 (1992), though the quote is famous and I have seen it in several other places as well.

- There’s a ton on this, but A.B. Bosworth, “Alexander the Great: Greece and the Conquered Territories” in The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 6: The Fourth Century BC (second edition), 846-875 offers a good overview of the diversity of arrangements that might result from this process, while Engels, op. cit. discusses the logistics implications.