This week, I’m going to offer a fairly basic overview of the concept of strategic airpower, akin to our discussions of protracted war and nuclear deterrence. While the immediate impetus for this post has been Russian efforts to use airpower coercively in Ukraine, we’re going to focus more broadly on the topic: what is strategic airpower, where did the idea come from, how has it been used and does it actually work? As with nuclear deterrence, this is a much debated topic, so what I am going to present here is an overview of the sort I’d provide for an introductory class on the topic and then at the end we’ll cover some of the implications for the current conflict in Ukraine. That said, this is also an issue where I think most historians of the topic tend to part ways with both some things the public think they know about the topic and some of the things that occasionally the relevant branches of the military want to know about the topic; in any case I am going to try to present a fairly ‘down the middle’ historian’s view of the question.1

Before we dive in, we need to define what makes certain uses of airpower strategic because strategic airpower isn’t the only kind. The reason for the definition will emerge pretty quickly when we talk about origins, but let’s get it out of the way here: strategic airpower is the use of attack by air (read: bombing) to achieve ‘strategic effects.’ Now that formal definition is a bit tautological, but it becomes clarifying when we talk about what we mean by strategic effects; these are effects that aim to alter enemy policy or win the war on their own.

Put another way, if you use aircraft to attack enemy units in support of a ground operation (like an invasion), that would be tactical airpower; the airpower is a tactic that aims to win a battle which is still primarily a ground (or naval) battle. We often call this kind of airpower ‘close air support’ but not all tactical airpower is CAS. If you instead use airpower to shape ground operations – for instance by attacking infrastructure (like bridges or railroads) or by bombing enemy units to force them to stay put (often by forcing them to move only at night) – that’s operational airpower. The most common form of this kind of airpower is ‘interdiction’ bombing, which aims to slow down enemy ground movements so that friendly units can out-maneuver them in larger-scale sweeping movements.

By contrast strategic airpower aims to produce effects at the strategic (that is, top-most) level on its own. Sometimes that is quite blunt: strategic airpower aims to win the war on its own without reference to ground forces, or at least advance the ball on winning a conflict or achieving a desired end-state (that is, the airpower may not be the only thing producing strategic effects). Of course strategic effects can go beyond ‘winning the war’ – coercing or deterring another power are both strategic effects as well, forcing the enemy to redefine their strategy. That said, as we’ll see, this initially very expansive definition of strategic airpower really narrows quite quickly. Aircraft cannot generally hold ground, administer territory, build trust, establish institutions, or consolidate gains, so using airpower rapidly becomes a question of ‘what to bomb’ because delivering firepower is what those aircraft can do.

As an aside, this sort of cabined definition of airpower and thus strategic airpower has always been frustrating to me. It is how airpower is often discussed, so it’s how I am going to discuss it, but of course aircraft can move more than bombs. Aircraft might move troops – that’s an operational use of airpower – but they can also move goods and supplies. Arguably the most successful example of strategic airpower use anywhere, ever is the Berlin Airlift, which was a pure airpower operation that comprehensively defeated a major Soviet strategic aim, and yet the U.S. Air Force is far more built around strategic bombing than it is around strategic humanitarian airlift (it does the latter, but the Army and the Navy, rather than the Air Force, tend to take the lead in long-distance humanitarian operations). Nevertheless that definition – excessively narrow, I would argue – is a clear product of the history of strategic airpower, so let’s start there.

And once again before we get started, a reminder that the conflict in Ukraine is not notional or theoretical but very real and is causing very real suffering, including displacing large numbers of Ukrainians as refugees, both within Ukraine and beyond its borders. If you want to help, consider donating to Ukrainian aid organizations like Razom for Ukraine or to the Ukrainian Red Cross. As we’re going to see here, airpower offers no quick solution for the War in Ukraine for either party, but the recent Russian shift to air attacks on civilian centers sadly promises more suffering and more pressing need for humanitarian assistance for Putin’s many victims.

Finally, a content warning: what we’re discussing today is largely (though not entirely) the application of airpower against civilian targets because it turns usually what ‘strategic’ airpower ends up being. This is a discussion of the theory, which means its going to be pretty bloodless, but nevertheless this topic ought to be uncomfortable.

On with our topic, starting with the question of where the idea of strategic airpower comes from.

That Damned Trench Stalemate Again!

In my warfare survey, I have a visual gag where for a week and a half after our WWI lecture, every lecture begins with the same slide showing an aerial photograph (below) of the parallel trenches of the First World War because so much of the apparatus of modern warfare exists as a response, a desperate need to never, ever do the trench stalemate again. And that’s where our story starts.

Fighting aircraft, as a technology in WWI, were only in their very infancy. On the one hand the difference between the flimsy, unarmed artillery scout planes of the war’s early days and the purpose-built bombers and fighters of the war’s end was dramatic. On the other hand the platforms available at the end of the war remained very limited. Once again we can use a late-war bomber like the Farman F.50 – introduced too late to actually do much fighting in WWI – as an example of the best that could be done. It has a range of 260 miles – too short to reach deep into enemy country – and a bomb load of just 704lbs. Worse yet it was slow and couldn’t fly very high, making it quite vulnerable. It is no surprise that bombers like this didn’t break the trench stalemate in WWI or win the war.

However, anyone paying attention could already see that these key characteristics – range, speed, ceiling and the all-important bomb-load – were increasingly rapidly. And while the politicians of the 1920s often embraced the assumption that the War to End All Wars had in fact banished the scourge of war from the Earth – or at the very least, from the corner of it they inhabited such that war would now merely be a thing they inflicted on other, poorer, less technologically advanced peoples – the military establishment did not. European peace had always been temporary; the Peace of Westphalia (1648) and the Congress of Vienna (1815) had not ended war in Europe, so why would the Treaty of Versailles (1919)? There had always been another war and they were going to plan for it! And they were going to plan in the sure knowledge that the bombers the next war would be fought with would be much larger, faster, longer ranged and more powerful than the bombers they knew.

One of those interwar theorists was Giulio Douhet (1869-1930), an Italian who had served during the First World War. Douhet wasn’t the only bomber advocate or even the most influential at the time – in part because Italy was singularly unprepared to actually capitalize on the bomber as a machine, given that it was woefully under-industrialized and bomber-warfare was perhaps the most industrial sort of warfare on offer at the time (short of naval warfare) – but his writings exemplify a lot of the thinking at the time, particularly his The Command of the Air (1921).2 But figures like Hugh Trenchard in Britain or Billy Mitchell in the United States were driving similar arguments, with similar technological and institutional implications. But first, we need to get the ideas.

Like many theorists at the time, Douhet was thinking about how to avoid a repeat of the trench stalemate, which as you may recall was particularly bad for Italy. For Douhet, there was a geometry to this problem; land warfare was two dimensional and thus it was possible to simply block armies. But aircraft – specifically bombers – could move in three dimensions; the sky was not merely larger than the land but massively so as a product of the square-cube law. To stop a bomber, the enemy must find the bomber and in such an enormous space finding the bomber would be next to impossible, especially as flight ceilings increased. In Britain, Stanley Baldwin summed up this vision by famously quipping, “no power on earth can protect the man in the street from being bombed. Whatever people may tell him, the bomber will always get through.” And technology seemed to be moving this way as the possibility for long-range aircraft carrying heavy loads and high altitudes became more and more a reality in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Consequently, Douhet assumed there could be no effective defense against fleets of bombers (and thus little point in investing in air defenses or fighters to stop them). Rather than wasting time on the heavily entrenched front lines, stuck in the stalemate, they could fly over the stalemate to attack the enemy directly. In this case, Douhet imagined these bombers would target – with a mix of explosive, incendiary and poison gas munitions) the “peacetime industrial and commercial establishment; important buildings, private and public; transportation arteries and centers; and certain designated areas of civilian population.” This onslaught would in turn be so severe that the populace would force its government to make peace to make the bombing stop. Douhet went so far to predict (in 1928) that just 300 tons of bombs dropped on civilian centers could end a war in a month; in The War of 19– he offered a scenario where in a renewed war between Germany and France where the latter surrendered under bombing pressure before it could even mobilize. Douhet imagined this, somewhat counterintuitively, as a more humane form of war: while the entire effort would be aimed at butchering as many civilians as possible, he thought doing so would end wars quickly and thus result in less death.

Clever ideas to save lives by killing more people are surprisingly common and unsurprisingly rarely turn out to work.

Assumptions and Institutions

Now before we move forward, I think we want to unpack that vision just a bit, because there are actually quite a few assumptions there. First, Douhet is assuming that there will be no way to locate or intercept the bombers in the vastness of the sky, that they will be able to accurately navigate to and strike their targets (which are, in the event, major cities) and be able to carry sufficient explosive payloads to destroy those targets. But the largest assumption of all is that the application of explosives to cities would lead to collapsing civilian morale and peace; it was a wholly untested assumption, which was about to become an extremely well-tested assumption. But for Douhet’s theory to work, all of those assumptions in the chain – lack of interception, effective delivery of munitions, sufficient munitions to deliver and bombing triggering morale collapse – needed to be true. In the event, none of them were.

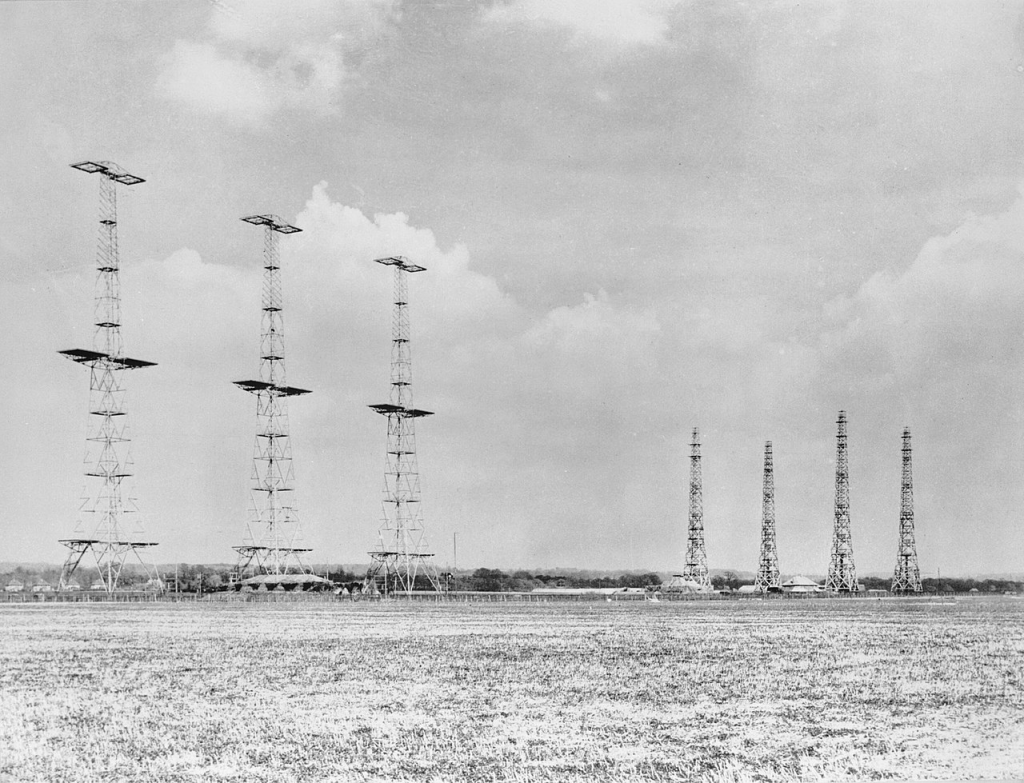

What Douhet couldn’t have known was that one of those assumptions would already be in the process of collapsing before the next major war. The British Tizard Commission tested the first Radio Detection and Finding device successfully in 1935, what we tend to now call radar (for RAdio Detection And Ranging). Douhet had assumed the only way to actually find those bombers would be the venerable Mk. 1 Eyeball and indeed they made doing so a formidable task (the Mk. 1 Ear was actually a more useful device in many cases). But radar changed the game, allowing the detection of flying objects at much greater range and with a fair degree of precision. The British started planning and building a complete network of radar stations covering the coastline in 1936, what would become the ‘Chain Home’ system. The bomber was no longer untrackable.

That was in turn matched by changes in the design of the bomber’s great enemy, fighters. Douhet had assumed big, powerful bombers could not only be undetected, but would fly at altitudes and speeds which would render them difficult to intercept. Fighter designs, however, advanced just as fast. First flown in 1935, the Hawker Hurricane could fly at 340mph and up to 36,000 feet, plenty fast and high enough to catch the bombers of the day. The German Bf 109, deployed in 1937 (the same year the Hurricane saw widespread deployment) was actually a touch faster and could make it to 39,000 feet. If the bomber could be found, it could absolutely be engaged by such planes and those fighters, being faster and more maneuverable could absolutely shoot the bomber down. Indeed, when it came to it over Britain and Germany, bombers proved to be horribly vulnerable to fighters if they weren’t well escorted by their own long-range fighters.

Cracks were thus already appearing in Douhet’s vision of wars won entirely through the air. But the question had already become tied up in institutional rivalries in quite a few countries, particularly Britain and the United States. After all, if future wars would be won by the air, that implied that military spending – a scarce and shrinking commodity in the interwar years – ought to be channeled away from ground or naval forces and towards fledgling air forces like the Royal Air Force (RAF) or the US Army Air Corps (soon to be the US Army Air Forces, then to be the US Air Force), either to fund massive fleets of bombers or fancy new fighters to intercept massive fleets of bombers or, ideally both. Just as importantly, if airpower could achieve independent strategic effects, it made no sense to tie the air arm to the ground by making it a subordinate part of a country’s army; the generals would always prioritize the ground war. Consequently, strategic airpower, as distinct from any other kind of airpower, became the crucial argument for both the funding and independence of a country’s air arm. That matters of course because, while we are discussing strategic airpower here, it is not – as you will recall from above – the only kind. But it was the only kind which could justify a fully independent Air Force.

Upton Sinclair once quipped that, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on him not understanding it.” Increasingly the salaries of airmen in the United States and Britain depended on understanding that strategic bombing – again, distinct from other forms of airpower – could work, would work and would be a war winner.

The Theory Is Tested

The Second World War provided the ‘opportunity’ for the theory to be tested, frankly to destruction. To the destruction of quite a lot of things, the theory included. Nazi Germany conducted the first terror bombings3 – that is, bombing attacks on civilian targets designed to sow fear and demoralize the enemy – against Poland in the opening hours of the war, though in the event the collapse of the badly outnumbered and outgunned Polish army on the ground made the Nazi terror bombings (like most of what the Nazis did) an exercise in pointless, excessive cruelty.

Instead the first real test of the theory came in an odd form: the Battle of Britain (July-October, 1940). The oddity here is that the ostensible initial goal of German air operations against Britain was not to compel surrender by demoralizing the populace, but rather to open Britain to the credible threat of invasion by destroying the Royal Air Force and prohibiting the Royal Navy from operating within range of German airbases. In this sense it would have been the threat of a land invasion which would have achieved the strategic effect, with airpower merely enabling that operation.

That of course isn’t how it turned out. While the Luftwaffe initially began with attacks against shipping, progressing to attacks on airbases and air production, beginning in August 1940 the Luftwaffe began escalating attacks on civilian areas (the degree to which that was intentional remains contested). The British responded with bombing raids against Berlin, at which point Hitler and Göring retaliated with an intensive campaign of urban bombing which would become known as the ‘blitz.’ Hitler would claim these attacks were reprisals (Vergeltungsangriffen, ‘revenge attacks’) for the British bombing Berlin, which was frankly pretty rich hypocrisy coming from the fellow who had terror-bombed the Poles in 1939.4 But that progression brings an interesting distinction here between intentional strategies of using bombing to collapse morale and the reversion to civilian bombing as pure punishment. As we’ll see, it is a predictable human response when an effort is failing to attempt to punish the opponent for the temerity of not losing; this behavior is especially pronounced in personalistic dictatorships but certainly not restricted to them. Naturally bombing against civilian targets, since its introduction, has often been the means of this sort of punishment response; more broadly this kind of thing fits into the error of ‘emotive strategy,’ which we’ve discussed before.

Nazi strategic incoherence aside, the Blitz was revealing in quite a few ways. First, it demonstrated quite effectively that the bomber would not in fact always get through – or more correctly that a defender could inflict meaningful attrition on bombers through ground-based anti-air and (even more importantly) fighter intercept. Radar (in the form of the Chain Home system) was particularly important for allowing interceptors to be concentrated on incoming bomber formations rather than having to disperse to search the sky. Second, German efforts to put bombs on specific industrial targets were, if you will pardon the pun, decidedly hit-or-miss. Moreover it turned out that destroying a city required a lot more bombs than anyone had anticipated; the Luftwaffe dropped about 40,000 tons of bombs on London during the Blitz – 133 times5 the quantity Douhet thought would compel a country to surrender – and didn’t manage to permanently destroy or even substantially hinder the city. British production rose over the period, albeit more slowly than it might otherwise have.

But perhaps most ominously for the theory, the Blitz didn’t seem to have meaningfully dampened British morale. Indeed, to the contrary – and get ready to hear this phrase a lot – being bombed hardened civilian will to resist. This hardly discredited the theory though, least of all among the British (or the soon-to-be-in-the-war Americans) who promptly decided to test it themselves.

The Theory Is Tested…Again

The Royal Air Force and the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) both conducted strategic bombing campaigns against Germany during WWII, though along ostensibly different principles. In the United States, an air campaign expressly aimed at killing German civilians to compel surrender was politically unpalatable (there were fewer such compunctions against doing this to Japan, due in no small part to racism), so the theory the USAAF went with was aimed at production rather than morale, which had emerged in the then U.S. Army Air Corps during the 1930s. The idea, informally called ‘Industrial Web Theory,’ was that an enemy’s industrial capacity was a fairly fragile web which could be disrupted by striking key nodes and that these disruptions would cause military production – ammunition, weapons, fuel and all of the other necessary things for ground warfare – to come to a near-halt, depriving the enemy of the ability to field a modern army and thus forcing them to surrender. Doing this would require being able to accurately deliver bombs to smaller targets (factories and railyards, not cities) but the USAAF was confident that such accuracy was possible, particularly with the Norden bomb sight, if bombing was done by day.

The British, meanwhile, were in a different situation. Unlike the USA, with its near infinite capabilities to build bombers and train air crews, Britain was limited in both; daylight bombing promised unsustainable casualty rates and so the RAF would have to bomb at night. That in turn meant accuracy was out of the question; cities went dark at night leaving bombers at high altitudes with no visible landmarks to navigate by.6 Meanwhile, the experience of the Blitz had left British politicians and the public with far fewer qualms about ‘morale bombing’ (an Allied euphemism for terror bombing) in return. So the RAF settled on ‘area bombing’ as a strategy, which was essentially strategic bombing along the lines suggested by Douhet: bomb until civilian morale cracked.

These strategies and their applications remain deeply controversial, as you might imagine. I find one of the better arguments for the value of bombing to be Richard Overy’s chapter in Why The Allies Won (1995); the degree to which his case is muted and partial speaks volumes. In practice while strategic bombing may have achieved positive outcomes for the Allies, they were mostly unintended outcomes, though to be fair to Allied leadership in many cases it couldn’t have been clear ahead of time how poorly the theory would perform.7 Instead, just about every key assumption that formed the foundation of morale bombing and industrial web theory and Douhet’s whole apparatus itself turned out to be wrong.

First, the accuracy to enable pin-point targeting of industrial facilities simply wasn’t there. By way of example (drawn from the chapter on strategic bombing in Lee, Waging War (2016)), in 1944 the allies attempted from May to November in a series of raids to destroy an oil plant in Leuna, Germany. The plant was 1.2 square miles in total size and yet 84% of all bombs missed. In the USAAF, the problem of accuracy led to a shift in tactics, from aiming for factories to area bombing intended to ‘de-house workers,’ which is an incredibly bloodless euphemism for daylight bombing raids against dense urban housing. Consequently, industrial damage was far less than was hoped. Instead of falling, German production continued to rise – indeed, it tripled – until territorial losses to the advancing Soviet and Allied armies finally curtailed production. Overy argues, persuasively, I think, that bombing did serve to stunt German production growth, but the strategic effect of disabling German industry to the point that the war couldn’t be continued was wildly, overwhelmingly out of reach. The opponent could, after all, react, dispersing and protecting industry, limiting the impact of bombing campaigns. Industrial bombing thus achieved something, but it is unclear if it achieved anything to be worth the tremendous investment in vast fleets of bombers necessary to do it.

Meanwhile it rapidly become apparent that the unescorted bomber would most certainly not always get through. The Allies lost some 37,000 aircraft in the strategic bombing campaign. Now as Overy notes this actually led to one of the unintended successes of the effort: American and British bombers diverted massive amounts of German aircraft and anti-aircraft artillery away from the Eastern Front where the Germans badly needed it. By the end of 1943, there were 55,000 AA guns (including 75% of the 88mm guns, which were very effective anti-tank guns as well), while German aircraft production shifted over to primarily producing fighters, with bomber production falling from 50% of the total in 1942 to just 18% in 1944. And even then, Germany simply could not match American production potential, especially as long-range escorts became available. In practice one of the most important contributions of the strategic bombing effort was, ironically, luring the Luftwaffe into the air where it could be destroyed; the effort of trying to stop the bombers essentially wore the Luftwaffe down to a nub, greatly easing the path of ground operations (including the D-Day invasion). This was very much not the intended outcome of operations, but perhaps the most useful thing strategic bombing accomplished in the war.

Finally, in the aftermath of the war, efforts to survey the morale impact of the bombing largely concluded that – wait for it – being bombed hardened civilian will to resist. Together the allies had dropped some 2,500,000 tons of bombs – eight thousand times8 the quantity Douhet predicted would induce surrender – and the net effect of this was to increase German resolve to resist. You would be forgiven for assuming that this would put to rest Douhet’s notion that with enough conventional bombs, one could collapse civilian will and end a conflict from the air.

We’re Still Testing This Theory!?

Despite this, industrial web theory promptly became the doctrinal core of the newly independent United States Air Force in 1947. Part of the reason was the apparently different course that strategic bombing had produced against Japan. To the newly independent air force, nuclear weapons were simply a logical extension of strategic bombing and nuclear weapons had, in their view, worked to compel Japanese surrender. Now I want to note again we’re not going to dive down the nuclear rabbit-hole here, we’ve done that before. I do want to note that current scholarship on the factors that led to Japanese surrender is very complex; whatever simple summary of it you have heard – either that the atomic bombs definitely did or definitely did not lead directly to Japanese surrender – is almost certainly wrong given the complexity of the question. But that complexity was a hard-won product of years of scholarship, based on documents which weren’t translated or available in the 1940s, had the new Air Force wanted to read them. To many in the new Air Force the lesson was simple (and, again, wrong in it simplicity): strategic bombing worked, as it had compelled Japanese surrender without an invasion. Few modern historians, I think, would agree with so simple a lesson.

Consequently the new Air Force oriented itself primarily around this strategic bombing mission, focused heavily on the use of nuclear weapons against civilian targets to compel surrender; the nuclear innovation would at last have the explosive power to deliver Douhet’s prophecy. There is, of course, also a degree of institutional interest here: strategic bombing with nuclear weapons provided a ready justification for the creation of and continued funding of an independent Air Force, because it envisaged that Air Force would itself engage in independent combat operations, rather than merely engage in combat operations in support of ground forces. Ironically, as I hinted at earlier, it is in this formative period that strategic airpower achieved what, as far as I can tell, is its only clear, unqualified success at producing strategic outcomes in the absence of ground force: the Berlin Airlift (1948-9) and to be fair some Air Force doctrine does recognize this, though it seems to me more often that definitions of airpower are oriented around kinetic effects (bombing) to the degree that other modes of non-kinetic airpower are marginalized. Nevertheless strategic airpower in the Cold War Air Force largely meant strategic bombing, either to crush enemy will or disable enemy industry.

Industry bombing and industrial web theory was thus the framework the Air Force had going into both the Korean and Vietnam Wars. Both wars presented a major problem: the industry actually sustaining the war effort wasn’t in the combat zone and couldn’t be attacked due to political concerns. During the Korean War, North Korean forces were largely supplied by China and the USSR; attacking either might trigger a nuclear retaliation and so was rejected. Instead, the United States used a campaign of ‘air pressure’ to try to compel a favorable peace, essentially resorting – as they had in WWII – to a Douhet-style bombing attack on the will to continue the fight when industrial bombing failed. This campaign was escalated to attacks on key dams, which could in turn damage not only power generation but also cause flooding and famine. In practice these efforts do not seem to have been a major factor in the eventual success of armistice negotiations.

In Vietnam, the same problem complicated any effort at industrial bombing: the factories that supplied the North Vietnamese forces (both the regular PAVN and irregular NLF) were in China and especially the USSR. Moreover the population was not broadly dependent on centralized utilities (like electricity) which could be bombed. Nevertheless, the United States embarked upon ‘Operation Rolling Thunder,’ (1965-1968) a bombing campaign over parts of North Vietnam which aimed to steady increase ‘pressure’ by bombing North Vietnamese industrial and transportation targets, as well as degrading North Vietnam’s air defenses. Supporters of the campaign at the time and subsequently have long claimed that the effort was hindered by political constraints which set certain targets and areas as off-limits, but it is hard not to also note that pulling the People’s Republic of China directly into the war would have been a pretty catastrophic failure and presented dangerous escalation scenarios given that the PRC had become a nuclear power in 1964. The political constraints were real and as we’ve discussed, political (that is, strategic) realities must dictate operational and tactical decisions, not the other way around.

Nevertheless over the course of the operation the United States dropped some 643,000 tons of bombs on North Vietnam, a fraction of the even larger total used during the entire war (though the great majority of that larger total, around 8,000,000 tons, were dropped on targets outside of North Vietnam). The net effect on the industrial basis of the war effort was not significant. Meanwhile, Mark Clodfelter has argued (inter alia), in The Limits of Air Power (2006) that the campaign actually harmed US political objectives and helped North Vietnamese goals, securing North Vietnam’s firm support from both its populace and its international sponsors while at the same time dividing the American public and thus sapping support for the war. Once again – wait for it – being bombed hardened civilian will to resist.

But Maybe It Could Work For Us?

Subsequent efforts in Vietnam may have been more successful. “Linebacker” – a bombing campaign in 1972 aimed primarily at interdicting the transportation of supplies from North Vietnam to the fighting in South Vietnam – helped to force North Vietnam to peace talks. A second operation, creatively named Linebacker II (also 1972) was also used when talks stalled to try to compel North Vietnamese leadership to compromise. What I find particularly striking about both efforts here – and keep a pin in this for a moment because we’ll come back to it – is that they achieved their goals, but their goals were limited and focused on political leadership rather than popular support for the war. That is already a major revision from Douhet’s vision of producing strategically significant popular morale collapse. They didn’t convince North Vietnam to completely abandon its goal of reunification through military force – that would happen just three years later in 1975 – but rather merely convinced North Vietnamese leaders to essentially make fairly minor modifications to short-term goals and timetables, mostly a mere delay.

Strategic airpower was supposed to be the lever that could move mountains and yet by end of the 1970s the best it had managed to do was shift a falling stone a few feet to the right (though it ended up falling in the same place in the end).

However, in the push to effectively target North Vietnamese logistics, the United States had begun developing increasingly precise delivery systems for its bombs as well as progressively more sophisticated observation and targeting technology (though, as we’ll see, these don’t always develop in the order one would like). More accurate systems made it possible to contemplate engaging a wider range of targets. Consequently by the time the first Gulf War (1991) rolled around, it was possible to contemplate a new kind of strategic airpower. Tasked with creating a plan for the initial air campaign over Iraq for Operation Desert Storm, Col. John A. Warden III presented a model, called the ‘Five-Ring’ model, of a modern state and its capacity.

The idea in application was that by striking the inner rings – consisting of national leadership, communications and key industrial infrastructure (not all of the industry, but a few key components of it) – it would be possible to paralyze a country, causing it to collapse and thus – as is always the promise of strategic airpower – winning the war from the air. It’s hard not to see this as some ways a strategic extrapolation of the sort of operational-tactical paralysis envisaged by Air Land Battle, but raised to the strategic level and applied from the air. This model was created for a very specific air campaign and so was immediately tested in that air campaign.

On the one hand, the air campaign over Kuwait and Iraq in 1991 was clearly effective; Coalition forces achieved victory in the Gulf War far faster and at far less cost than had generally been anticipated. On the other hand, air operations in both the first Gulf War and then more than a decade later during the invasion of Iraq in 2003, it was not clear that any kind of strategic paralysis was achieved. The DoD’s own report, issued in 1993 (Cohen and Keaney, Gulf War Air Power Survey (1993)) noted first that only some 15% of strikes were against ‘strategic’ targets, while strikes against Iraqi ground forces consumed 56% of strikes; as Coalition air forces exhausted their list of strategic targets, they switched over to strikes against ground forces.

Despite effectively running out the entire list of strategic targets, Cohen and Keaney nevertheless conclude that strategic effects were broadly not achieved. Despite striking the Iraqi communications network with more than 580 strikes, “the Iraqi government had been able to continue launching Scuds” and “sufficient ‘connectivity’ persisted for Baghdad to order a withdrawal from the theater [Kuwait] that included some redeployments aimed at screening the retreat.” Consequently, “these attacks clearly fell short of fulling the ambitious hope” to “put enough pressure on the regime to bring about its overthrow and completely sever communications between Baghdad and their military forces.” Instead airpower continued to show its greatest impact through non-strategic effects: destroying or disorienting enemy ground forces in order to make the advance of friendly ground forces quicker and easier. That pattern would, by the by, functionally repeat in the 2003 invasion of Iraq as well. Good old interdiction and close air support helped to achieve what strategic bombing, after more than a half century of attempts, still could not.

The other common examples of the strategic use of airpower are the two NATO interventions against Serbia, first over Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1995 and then in response to Serbian ethnic cleansing in Kosovo in 1999. But a distinction here has to be made: in Bosnia, NATO intervention in the air was in support of a significant ground force tasked with implementing UN resolutions establishing no-fly zones and maritime embargoes. When NATO escalated to direct bombing with Operation Deliberate Force, it was primarily close air support, supporting ground operations by the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Croatian Army, not as an independent strategic operation. So we may safely set that aside.

That leaves Operation Allied Force in response to Serbian ethnic cleansing of ethnic Albanians in Kosovo in 1999. As Mary Elizabeth Walters – an expert in this particular conflict – noted recently on Twitter, the air campaign was initially aimed at degrading the Serbian military’s ability to function but rapidly switched to bombing ‘dual use’ infrastructure in an effort to coerce Slobodan Milošević. While civilian casualties absolutely happened and there were a series of serious mistakes in targeting or timing, this was not an effort at Douhet-style morale bombing. Instead the aim was to shift Milošević’s strategic calculus both by raising the cost of further ethnic cleansing but also to undermine his support among the key elites who owned all of the infrastructure that was getting blown up. And it worked in altering Milošević’s political calculus (though his lack of international support was also a factor) but it did not succeed in immediately causing the collapse of his regime (though that did happen in late 2000 as as consequence of international sanctions damaging the economy). At the same time, while the bombing campaign was happening, Serbian forces accelerated the ethnic cleansing campaign; efforts to slow down that process with strikes from the air largely failed due to difficulty in targeting the Serbian ground forces in the absence of a ground presence.9

Implications Today

This joke kindly borrowed from B.A. Friedman.

Overall then, the promise of strategic airpower, that it could win wars entirely or primarily from the skies, turns out so far to have been largely a mirage; in about 80 years of testing the theory, strategic bombing has yet to produce a clear example where it worked as intended. Instead, strategic airpower must be one of the most thoroughly tested doctrines in modern warfare and it has failed nearly every test. In particular, Douhet’s supposition that strategic bombing of civilian centers could force a favorable end to a conflict without the need to occupy territory or engage in significant ground warfare appears to be entirely unsupportable.10 Nuclear weapons do not seem, so far, to have actually changed this; nuclear deterrence does not aim at ‘will’ in the Clausewitzian sense (drink!) but rather on altering the calculus of leaders and politicians through the threat of annihilation. In the event of an actual conflict, the public’s desire not to be nuked – which would be the key target in a Douhet-style morale bombing campaign – appears to factor very little into actual decision-making. No one checks the polls before intentionally embarking on nuclear war or in the minutes a leader might have to deliberate on ordering a second-strike.

Instead, efforts to use strategic bombing to coerce surrender have repeatedly shown that being bombed hardens civilian resolve to continue resisting. By contrast, bombing can have some effect on industrial production, but only in wars where that production matters and is available to be bombed; at the same time the impact of that industrial bombing is also likely to be sharply reduced by enemy efforts to shield industrial capacity from bombing and at the same time to prioritize military production with what industrial capacity remains. Inducing full strategic paralysis has never been successfully demonstrated, although causing disorientation, making ground operations easier, by striking communications does seem to work but of course that isn’t quite a strategic use of airpower anymore, since it is in support of ground operations (which then achieve the strategic objectives).

That isn’t to say that independent airpower has no coercive effect. However the coercive effect seems to be substantially more limited than the coercion available to ground forces (or naval forces for island nations), which makes sense given the greater ability of ground forces to remove resources from the enemy state. After all, a bombed city has its production cut by some percentage, but a captured city provides no support for its former regime. That limited coercive effect is fairly clearly displayed in the Linebacker operations, which convinced North Vietnam to delay, but not abandon, its plans for the conquest of the South. Crucially, the coercive effect of these bombing efforts is not only limited, but it is also not delivered via popular will but rather through the political calculus of the leadership (again, politics not will, in the Clausewitzian sense; drink!), balancing the costs of sustaining aerial bombardment against the benefits of holding out. Since those costs tend to be limited compared to ground conquest, the concessions these leaders are willing to make are also limited. The use of strategic airpower to coerce can deflect but not reverse policy, but under conditions where a stronger power aims only to produce limited concessions from a weaker power, there is some promise in the use of airpower to create that deflection. However, the repeated mistake militaries have made is attempting to use airpower as the lever to force major concessions or even total capitulation; the leverage for this appears to be nowhere near good enough.

So why does strategic bombing, especially terror or ‘morale’ bombing seem so resilient as an idea in so many militaries? Well, the first answer goes back to institutional incentives and how the salaries of a great many aviators depend on not understanding just how weak a strategy strategic airpower is. “The purpose of our air forces is to win wars” is a much better argument to take to political leaders for funding than “the purpose of our air forces is to support our ground forces.” The latter implies that the ground forces should set priorities and that the air forces ought to, for the most part, subordinate their efforts to those priorities. And of course given the choice of priorities, ground forces will tend to prioritize…ground forces, with deleterious career and prestige outcomes for everyone else. Combine this with the fact that the sort of folks who join a military’s air branch – any military’s air branch – are going to tend to be the sort of people who already believe in airpower and it isn’t hard to see how strategic airpower (as distinct from other forms of airpower) rapidly becomes a solution in search of a problem.

The second answer seems to be that strategic airpower is both intuitive and tempting. It is intuitive in that it makes a certain immediate sense, even though like many intuitive things it is not really true. Nevertheless it feels like it should work and moreover – and this is the tempting bit – it would be really nice (for some decision-makers) if it did work, since it would offer the promise of exerting a lot of strategic leverage without risking the casualties and unpredictable messiness of ground operations. It might shorten horrible wars, or even bring and end to war itself (of course in practice it appears capable of neither of those things)! And so the answer of ‘we can bomb the problem away’ is always going to have an essential appeal even though it isn’t true, while the institutional incentives above practically guarantee that there will always be someone in the room who has an interest in believing and advocating for that ‘solution.’

Finally – and this is where I think we come back to the War in Ukraine – strategic bombing is emotionally satisfying even as it doesn’t work. It is a human instinct, when another human is doing something you don’t like – like refusing to lose on the battlefield – to retaliate, to punish that person. Strikes on civilian centers are perhaps the purest expression of this instinct, inflicting maximum pain (because civilian centers, unlike actual military targets, are not hardened against attack) at a minimum of risk and cost. We’ve discussed this ‘strategic sin’ before, terming it emotive strategy, but humans are emotional beings and so the temptation to ‘punish’ rather than pursue interests in a rational way will always exist.

Russian forces in Ukraine appear to follow this pattern of ‘behavior ’emotive strategy’ quite clearly, responding to setbacks with intensified long-range attacks on civilian centers. After the Kharkiv offensive stalled out, Russian forces began pounding the city with artillery in strikes that did more damage to civilians than the defenders of the city. Likewise, Russian airstrikes against explicitly humanitarian or civilian buildings escalated in Mariupol as the difficulty of taking the city escalated. Most recently, Russian forces have responded to setbacks the Kharkiv, Luhansk and Kherson oblasts, as well as a Ukrainian strike on the Kerch Bridge11 with strikes into Ukrainian civilian centers like Kyiv, increasingly using Iranian-manufactured loitering munitions (also called ‘suicide drones’ or in the case of the Shahed, I suppose we’d say a ‘martyr’ drone as that’s what ‘Shahed’ means) like the Shahed 136. This may in part be a response by Putin to domestic political conditions, a way of assuring his own hardliner supporters that he is ‘striking back’ in an emotionally satisfying, if strategically useless way (a fairly good example of ‘emotional choice theory‘ we discussed a few weeks back!).

At the same time, industrial bombing – which also has, at best, a somewhat mixed track record – isn’t an option for Russia for the same reasons it wasn’t an option for the United States in Vietnam or Korea: the industrial production which sustains the Ukrainian war effort is largely happening outside of Ukraine. Ukraine’s entire GDP pre-war was $189bn nominal. As of October 3rd, 2022, Ukraine has commitments of over $93bn in aid; $52.3bn of that is from the United States, a country against which Putin has very little leverage and which he most certainly cannot safely bomb. Assuming the United States’ European partners can tough it through the difficult economic headwinds of this winter, it is entirely within NATO resources to supply and fund Ukraine’s war effort indefinitely; in fact in terms of United States military spending it is an absolute steal, neutralizing a major competitor for a tiny fraction of the overall military budget. That aid (financial, military and humanitarian) moves through transit routes in NATO countries which are also effectively inviolate into western Ukraine where Russia has struggled to exert any serious airpower. Consequently, even interdicting these supplies – an effort akin to attacks on the Ho Chi Minh Trail during the Linebacker operations – is largely out of reach for Russia. That leaves just the morale bombing that Russia is doing now.

Edit: Some of the comments have argued that the recent Russian strikes are instead focused on electrical infrastructure and thus either valid logistical military targets or that their primary effect would be to cause Ukrainian civilians to freeze to death in winter (somewhat contradictory points). First, this is an excessively charitable reading of the pattern of Russian strikes; the power grid has been targeted, but hardly exclusively. The October 10 flurry of strikes included a residential apartment building in Zaporizhzhia, heavy civilian traffic in Taras Shevchenko Park, and some 35 private residential buildings. Which of course is consistent with a pattern of strikes that included, as noted here, a children’s hospital in Mariupol, a civilian shelter in a theater, the use of cluster munitions fired into apartment blocks in Kharkiv and so on. Which, of course, is consistent with Russian air operations earlier in Syria, which infamously used used U.N. lists of hospitals and other humanitarian facilities – designed to keep them out of the fighting – as a target list in order to force civilians to flee, in violation of the Laws of Armed Conflict. Which, of course, is consistent with Russian operations against the city of Grozny in 1999-2000, where failure to take the city by assault led to it being “the most destroyed city on Earth” as Russian forces resorted to bombing and artillery to demolish it. The pattern here, where Russian forces resort to whatever available means to destroy civilian infrastructure and kills civilians when facing battlefield failure is well established and at least two decades old; I see no reason to play pretend that this pattern isn’t clear. To the contrary, such consistency suggests doctrine – formal or informal – is at work here. If the Russian strikes here are anemic now, it seems only to be because Ukraine still has a functioning air defense system; Russia has not hesitated to engage in terror-bombing against parts of Ukraine (and Syria and Chechnya) that didn’t. Consequently, at best, Russia might claim to be waging an incompetent and woefully insufficient ‘industrial web’ style bombing campaign; if so this seems doomed to fail too for the same reason such efforts in Vietnam failed: the industrial capacity which sustains Ukraine is not located in Ukraine. But the pattern of Russian strikes and the history of Russian strategy in this regard leaves me disinclined to read these attacks very charitably and to instead read them as ‘punishment’ bombings, which of course is exactly what Putin said they were.

How likely is this Russian effort to succeed? Well, what we’ve seen so far is that air campaigns dropping millions of tons of high explosives have generally failed to compel a civilian population to seek peace. By contrast, a Shahed 136 drone carries a 40kg explosive payload. For comparison that means it would take ninety Shahed 136 drones to equal the payload of a single B-17 Flying Fortress and eight-eight thousand to equal the explosive power of the February, 1945 raids against Dresden. Those are efforts which, I feel the need to stress, didn’t work to collapse German civilian morale. Meanwhile the Shahed 136, while very cheap as a drone is very expensive as a bomb; at c. $20,000 a pop, matching the Dresden raids would require almost $2bn assuming the production capacity for that many drones existed (and it doesn’t). As Russia’s distance from Ukraine’s key civilian centers grows, the cost of delivering explosives to them increases,12 reducing Russia to demonstration attacks that, while horrible, have little chance of inflicting harm on Ukraine at a level that is remotely meaningful in this sort of war.

Consequently these ‘punishment’ strikes seem likely to merely harden Ukrainian will to resist and sustain international support for Ukraine; they are expensive and almost entirely counter-productive for Russia’s actual war aims. Such attacks won’t degrade Ukrainian will to continue a fight that most Ukrainians believe they are winning, but it will generate headlines and images which will reinforce public opinion among Ukraine’s supporters that Putin’s war effort has to be defeated. Crucially it strengthens arguments that NATO’s European members should tough it out through a difficult winter in response to manifest Russian inhumanity, the exact opposite of the outcome Putin needs. At the same time, Russian resources are finite; every rocket, missile or drone lobbed into Kyiv (or other Ukrainian cities) is a valuable munition no longer ready for use on the front lines. In many cases the munitions Putin is firing in these ‘revenge’ strikes are fairly expensive, fairly scarce precision munitions. The Shahed 136 is a lot cheaper than other long-range precision munitions, but one has to imagine that Russian troops would prefer Russian loitering munitions to try to target Ukrainian ground forces; longer-range precision platforms are very expensive. As with much ’emotive strategy,’ the things that make Putin ‘feel better’ push victory further away – or in this case, hasten defeat.

Which also explains neatly why Ukraine, despite being in a position to potentially lob munitions indiscriminately into cities like Belgorod, has mostly avoided doing that; Ukrainian forces having restricted themselves largely to clear logistics targets like ammunition and fuel depots or trainyards when striking beyond the front lines. Strategically, Ukraine needs to degrade Russian will (keep drinking!) – both political and civilian – while sustaining the international support that enables it to continue fighting and upon which Ukraine must pin its hopes for post-war rebuilding. Striking civilian targets, while perhaps emotionally satisfying to some after the brutality of Russian actions in Ukraine, would run counter to these goals: it would fragment Ukraine’s international support and potentially harden Russian public opinion in support of Putin and his war. Instead, Ukraine remains focused on winning the war in the field, degrading Russian morale by demonstrating that the war is unwinnable.

In conclusion then, the Russian escalation of air attacks on civilian targets seems unlikely to significantly alter the trajectory of the war beyond increasing the sum of human misery it inflicts. ‘Morale bombing’ of this sort, while coming with a long history, has an extremely low – arguably zero – success rate at achieving major political concessions. The promise of achieving in the air what cannot be done on the ground continues to suffer from the simple fact that as humans do not live in the air, conditions on the ground have greater coercive power; aircraft can only raid, they cannot occupy and humans can tolerate a stunning amount of raiding if they believe victory is still possible on the other side of it. The promise of strategic airpower remains just that: a promise, more frequently broken than kept.

The War in Ukraine seems set to prove once again that strategic bombing is no substitute for battlefield success.

- For a longer and more sustained discussion of the topic still pitched at a general readership, W.E. Lee, Waging War (2016), chapter 13 is focused on this topic, along with the related topics of nuclear deterrence and the emergence of precision-guided munitions. That’s the textbook I use when I teach the intro-level global history of warfare, so as you might imagine what follows here follows it fairly closely.

- Il dominio dell-aria. If that title sounds like it is echoing A.T. Mahan’s concept of ‘command of the sea’ that’s because it is.

- Of the war in Europe, not in general. Terror bombing itself was not new at this point, having been done all the way back in WWI with zeppelins.

- I think it is really worth stressing: both the Germany and Japan were using terror-bombing well before they were targeted by it, the Germans against Poland and the Japanese in China. One can argue that bombing civilians is nevertheless immoral in all cases, just as one might argue that no one should ever stab someone with a knife in a bar. However, if a fellow draws a knife in a bar and begins stabbing the patrons, it is hardly reasonable for that same fellow to cry foul play when the other patrons draw their knives and just so happen to have much bigger knives. It is, at that point, too late for the first fellow to opine on the fundamental incivility of knifing people.

- This figure is going to keep going up to increasingly incredible degrees.

- You could try dead reckoning, but that struggled to put bombs on the right city, much less the right building.

- I must admit I do not generally extend this charity to fellows like Arthur Harris or Curtis LeMay who were fairly explicit that their goal was to simply kill as many civilians as possible in order to end the war. At the same time, I thank heavens I have never been and presumably never will be in a position to be forced to weigh ending a war more quickly and thus saving some of the soldiers under my command against grievous civilian casualties.

- I told you it would keep going up.

- Poor weather also played a role.

- And again, before someone shouts ‘Japan in WWII,’ it seems necessary to note that Japan did not consider surrender until the Allies had effectively destroyed the Imperial Japanese Navy, dismembered much of the Japanese overseas empire, comprehensively cut Japanese shipping leading to critical shortages on the Japanese mainland and were clearly prepared to invade the Japanese homeland and a final Japanese offensive in their land war in China had clearly failed and the USSR had declared war and invaded Japanese Manchuria, leaving the Japanese army on mainland Asia in a position where it was sure to be destroyed. The promise of strategic airpower is not, ‘if you are in a position to decisively end the war by annihilating the enemy’s ground forces – at great cost – in the foreseeable future, strategic bombing may shorten the conflict.’ It was ‘win the war chiefly from the air.’ The Pacific War was not chiefly won from the air.

- Which, while we’re here, as the primary logistics link between the Kherson front and Russia (the East-West running railroads from Donetsk to Kherson are all either cut by Ukraine or too close to the front lines to use effectively), was an obviously valid military target. The strike against it also disabled a train moving what looked to be large amounts of fuel, which was also an obviously valid military target. The goal of the strike seems quite clearly to have been to interdict Russian logistics in support of the offensive in Kherson, which is completely legal under the Law of Armed Conflict. Unlike basically all of the Russian strikes into densely populated civilian areas.

- Tube artillery is cheaper but shorter range than rocket artillery is cheaper but shorter range than cruise missiles and jets and so on. The ratio of explosive to ‘expensive things delivering the explosive’ shifts in favor of the latter as distance rises.

Colour: https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x6kg32j

B&W: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tUeKeN9bXSE

Victory Through Air Power is a great example of optimism about strategic bombing

It starts with “Germany and Japan have had great success with tactical and operational air power” then goes to “We just need to send a bomber to blow up the Swastika Factory, and the war will end immediately” and “There’s no way to defeat Japan in the Pacific, we need to fly bombing missions out of Alaska”

The commitment to something that has never worked in 80 years reminds me of an entirely different field.

“If we build just one more lane, surely this time we will solve traffic congestion.”

I.e., something that was failing as early as the 1930s. But a lot of salaries, contracts, and wishful thinking rest on trying again and again.

This is a weird thing to say here, but isn’t the argument that strategic bombing is ineffective a little too.. historical?

Modern bombs are extremely accurate, and trying to make everything important in a country bomb-proof (or hidden) sounds very expensive.

And then on the other side, 12,000 tons of bombs over the course of months didn’t knock the UK out of WWII, but the US could drop the equivalent of hundreds of millions (or billions?) of tons of bombs on a country within a few hours these days. And didn’t the million or so tons of bombs dropped on Germany have a pretty big effect on morale and production?

Taken to an extreme, if the United States inexplicably got into a war to the death with Taiwan, the US Air Force *could* single-handedly win the war by literally destroying everything on the island. (The Air Force could probably figuratively do this to a lot of countries, including Germany)

That said, we don’t use bombs effectively for other reasons (they’re not very effective in proxy wars where you’re not willing to target the real enemy), and I imagine you’d argue that a theoretically-effective weapon that we can’t or won’t use isn’t very effective.

I just think this article is arguing that they’re not effective for technical reasons, and I think that’s not true anymore?

I’d say he covered that in the Iraq section: The US Air Force hit every single militarily strategic target they could think of, and it didn’t prevent the government from firing short-ranged ballistic missiles or organizing a retreat.

Furthermore, precision-guided munitions will not change the the terror bombing equation. Once the WWII terror bombing campaigns started in earnest, the problem wasn’t accuracy. The problem was that, short of quite literally killing or driving away every single inhabitant, at which point you have created a desert and called it victory, bombing population centers does not result in them thinking they should surrender. Instead, it results in them thinking you want to kill them for living there, which is usually called genocide, and people certainly do not respond to genocide attempts with surrender. And besides, you’re not going to successfully kill everyone because while you might not be able to harden everyone’s apartment buildings, you can certainly find enough bomb-hardened places to keep people alive during the raids themselves, and that takes a lot less space. So, to sum up, it looks like you’re advocating for genocide by personally delivering a bomb to every person in the city, because that’s the only way that PGMs might make it easier.

I’m not *advocading* for this, but wouldn’t Germany or Britain used the genocide/creating a desert and calling it victory strategy if it was technically possible? And now it is technically possible and the US just hasn’t been in a war where that would make any sense since WWII.

Also it seems relevant that this is so effective that no one is willing to fight wars where the other side would be capable and willing to use this strategy.

I’d argue it’s not technically possible. In nuclear terms, sure, you could turn a small country into a glassy desert… but you’d really want to do that from the safety and comfort of another atmosphere. If you’re sharing an atmosphere with that country… it’s pretty dicey. Maybe not strictly impossible, but the risks aren’t better than the proven, viable methods of achieving a victory on the ground. (Dunno about you, but I’d take 100,000 casualties in an invasion over 1,000 extra cases of cancer, per country, per year, for decades.)

In conventional terms, the US tried that in Vietnam. Take a look at the bomb tonnage sometime, and on the history of strategic bombing of the North, particularly of dams and of harbor mining. And the strategic analysis is divided on whether dropping 1,000lbs of explosives per human resident was simply useless, or whether it actively hardened resistance.

Now, if you want to argue that there’s some nonlinear breakpoint where okay, dropping a hundred thousand tons of bombs on a city of ten thousand people just makes them fight harder, but if you drop a hundred million tons of bombs on that same city they’ll surrender… Okay. Maybe. I can’t prove you wrong. And maybe there’s a nonlinear breakpoint where if you drink one scotch, it doesn’t affect your asthma at all, and if you drink ten scotches, it still doesn’t affect your asthma at all, but if you drink one thousand scotches suddenly you’ll be cured. In both cases, the evidence is about as good: two million tons of bombs did nothing to German resistance, seven million tons of considerably more accurate bombs did nothing to Vietnamese resistance, but maybe if Country X drinks a thousand scotches, they’ll surrender.

If we’re talking about death rather than surrender, the evidence suggests that bombing out human populations from even quite small areas from the air simply isn’t feasible. Look at Monte Cassino: after a solid month of air and artillery bombardment, it still took Polish bayonets to get the last defenders out. That’s one monastery! If you can’t obliterate the population of one monastery, in a whole month, with the advantage of observation from nearby ground troops… What chance do you have on a city, let alone a whole country?

Yes, I think this is non-linear. If I drop 1 gram of explosives on your house, it will make an annoying bang. If I drop a billion grams of explosives on your house it will cease to exist. It hardly matters if you surrender at that point. (And to be clear, the US military can blow up a monastary *without* nuclear weapons)

I don’t think modern proxy wars are useful comparisons since obviously you can’t effectively bomb the enemy’s industry if you’re not willing to target it (because those targets are in the Soviet Union and China), and we’re not willing to use nuclear weapons in these wars for a long list of good reasons (but “The Air Force couldn’t destroy Vietnam with nukes if they wanted to” isn’t one of them).

>I’d say he covered that in the Iraq section: The US Air Force hit every single militarily strategic target they could think of, and it didn’t prevent the government from firing short-ranged ballistic missiles or organizing a retreat.

I’d say you point out a flaw in this article that I overlooked at first: the criticism relies on a very vague definition of the goals of “strategic airpower”. We seemingly move from “it’s supposed to win the war all by itself” to “well if it didn’t prevent a few -as far as I know, quite innefective- missiles to be launched, so it failed”.

In a similar way, going back again and again to a speculation from post-ww1 era as a basis of what strategic air power ought to be is… doubtful? Is it really relevant to the post-ww2 and post-cold war expectation of strategic bombing?

What would you consider a strategic bombing “win” for ODS to look like? The Iraqi state manifestly survived, and the only notable civilian resistance movement seems to have been keyed to the triumph of UN ground forces- the Kurds and Shia didn’t start openly revolting until after the cease-fire and the hundred hour ground campaign, not during the month of intensive bombing, so that’s not civilian unrest.

The Iraqi army was very much overmatched by UN (largely US, obviously) forces, but they were still able to issue orders and have them be largely obeyed, so we don’t have network centric collapse either. What are the conditions that point to a victory for strategic airpower?

“Taken to an extreme, if the United States inexplicably got into a war to the death with Taiwan, the US Air Force *could* single-handedly win the war by literally destroying everything on the island.”

Lets us make this more extreme. Assume the US war aim is to make the Prime Minister of Grenada, a few miles off the US coast, comb his hair. And that they are willing to dedicate to this purpose the entire US nuclear arsenal.

It would still remain within the power of the PM to not comb his hair. If the US then fired off every nuke it had, the PM would still be able to not comb his hair. Indeed, the US would have less to threaten the PM with than it had before. The trouble with threatening people into doing something is that they always have the option of not doing it.

OTOH, if the US physically seized control of Grenada and its PM, it could have someone comb the PM’s hair, or even grab hold of his arms and hands and physically force him to do so.

Once you have seized control of a country, you no longer need threaten it into doing anything.

Sure, there are some strategic goals that the air force can’t guarantee success at. I’m not arguing with that. I’m saying in the WWII situation where you want to destroy a country’s industrial capacity or just kill everyone, modern extremely-accurate bombs and nuclear weapons would work.

My complaint is that the article makes it sound like bombs can’t work because they had technical problems that made them ineffective when they were first invented, and those technically problems have been solved and we just don’t use them effectively for other reasons (good reasons, to be clear, but not because we can’t destroy cities or hit specific targets with them).

The big issue with that is that the only war aim strategic airpower *may* be able to accomplish is “flatten every building, destroy all major population centers, and send the inhabitants back to before the industrial revolution”* and that aim is not that useful for nearly all things countries want.

Countries typically want to 1) continue existing, 2) increase their own strength, economic and military (to support 1) and then 3) have grand projects like converting other countries to their ideology or trying to avert the destruction of industrial civilizations on earth due to climate change (both of which actually support 1, but they don’t *have* to), in that order. Starting a war with the war aim above is not going to help 2, because by definition you destroyed nearly everything in the target country including all useful infrastructure and population and so it doesn’t give you more strength. It also may harm 1 and 2 through both physical (nuclear) and political fallout which causes your country to be worse of in the future. And for a lot of grand projects, except those of the shape “destroy civilization in this place”, those projects will also not be helped by this war.

Thus it is a very weird and unlikely war aim to have. The war aim of the Allies in WWII after all was not “kill everyone in (occupied) Europe” it was “dismantle the Nazi regime and force the German people to not start wars in future, and get the rest off the continent out from under the thumb of the Nazi regime” and even modern strategic airpower would struggle with that: It might be able to decimate high command before high command starts hiding better, but well dispersed industry would still go on and the Nazis don’t mind a lot of Jewish & occupied country labourers dying in the process.

* Note: literally killing every inhabitant will be very hard, which is why I phrased it like that. You need every place to be very near a nuke explosion so people don’t survive. For the W-53, biggest US ICBM arsenal nuke, the range for a near guaranteed kill is maybe around 4.5 kilometers for a ground burst shot (AKA a “the very wide geographic area is going to get fallout and all neighbour countries will be very angry), less for airburst. Taiwan is about 300×100 kilometer and will thus require a grid of about 1400 nukes (ignoring effects of terrain) to kill nearly everyone who is not in a basement. If you can’t launch all that at once, you will need to make some kind of sweep pattern that doesn’t allow people to go inbetween barrages as you load new missiles.

One notes we set out to demilitarize Germany. Then the Cold War hit

Some potential examples of successful uses of strategic airpower come to mind. First, wasn’t the “rapid dominance” strategy used by the United States against Iraq in 2003 considered to have been generally successful in its goals to “seize control of the environment and paralyze or so overload an adversary’s perceptions and understanding of events that the enemy would be incapable of resistance at the tactical and strategic levels”?

And what’s going on in Ukraine right now seems an appropriate example. Ukraine appears to have a strategy of targeting Russian supply and transportation to prevent them from fielding effective ground forces at the front. They’re using both fires and airpower to do that. Now you might argue that’s operational rather than strategic. And I’d agree that any given mission at a particular target is operational in nature, trying to prevent this specific supply or this specific route. But zoomed out the overall plan would be strategic wouldn’t it? And so wouldn’t the air component be considered strategic airpower?

Not in the sense of air power in and of itself winning a war. “Fighting back” is a bit too general to be called strategy 🙂

Those are excellent examples of *operational* air power.

Once again, in this sense “strategic air power” means that you win the war without any major surface component. No invasion, no blockade, no fleet action. Any offensive use of surface forces should be in support of the air campaign (like, say, commandos blowing up a SAM site) rather than supported BY the air. Perhaps, at the edge of the envelope, using ground forces to occupy an objective that has been rendered undefended by air power might fit. But we’re talking something like the occupation of Iceland here, not Monte Cassino or the like.

If the plan is “use air power to paralyze and disorient the Iraqi military so the Army and Marine Corps can invade and take over the country,” that is operational air power because the goal is to *facilitate* an invasion.

Further, it’s hard to argue that “rapid dominance” actually lived up to the description you quote. Certainly it degraded Iraqi coordination and ability to resist, yes, and the campaign is generally considered successful in terms of its actual goals, but… “the enemy would be incapable of resistance at the tactical level?” For that to be true, it would have to be the case that no Iraqi company, platoon, or even squad was able to mount an effective defense because they were all so confused or demoralized by bombing. And of course that’s nonsense, there were many effective defensive actions.

Now, if that wildly over-optimistic quote had been meant to be taken literally, then yes: air power which could turn “an at least mildly-effective military” into “just a bunch of dudes who mostly don’t even want to defend their homes and maybe a tiny minority of isolated guys who are going to start shooting wildly and without any plan when they see an American flag” would be capable of independently achieving strategic results. But it was never meant to be understood as anything but hyperbole, and as such it clearly describes an operational use of air power.

The thing I wonder about is the incredible accuracy of missiles and drones today. They really can destroy key infrastructure and I wonder how significant this will prove to be.

But we tried this with precision guided munitions against Iraq in 2003. The USAF destroyed every single target they could think up, and it still didn’t stop the enemy from fighting back or coordinating a fighting retreat. PGMs didn’t change the basic equation, and it’s hard to see how more-precisely guided munitions can do so.

Even given perfect targeting and perfect accuracy, using munitions “strategically” essentially dilutes or disperses the impact of a munition across the entirety of a nation. It’s similar to how a hologram or a neural network can suffer a certain amount of damage while still remaining mostly intact with some degradation. In other words, destroy 50% of a country- an ENTIRE country- from the air, and in theory it can still project 50% as much military power as it formerly did. Whereas a fraction of that much damage projected directly onto a military could obliterate it entirely. IMO the fallacy of strategic bombing is the belief that there exist a number of critical keypoints hiding in an enemy’s heartland, and that you can paralyze an enemy by destroying them. When in fact governments, economies and societies have evolved a degree of robustness against disruption. It’s similar to the fantasy of winning a war entirely by assassinating a nation’s leaders.

In principle it might be done if you had good enough intelligence about details of the enemy economy, and what had been damaged by what attack.

But even then you would just be weakening the enemy to make a conventional attack on land easier.

The only real example I can think of is the offensive against the German oil industry in 1944.

Wouldn’t that require solving the socialist calculation problem (and for another country, at that)? Not possible even in principle.

I think one could argue that the pacific war *was* won primarily in the air: Just in the tactical sense of carrier air strikes, not the strategic bombing campaign.

I do think there is a kind of self-perpetuating thing where strategic air warfare goes from “creating a strategic effect” to “winning the war on its own”. (partially because of the career incentives you mentioned) Like, to take another example, naval blockades rarely in themselves end the war, but claiming that they are either “not strategic” or not effective seems to be taking it a bit too far no? That is, it seems that a lot of these discussions are more about the grandiose claims of air-proponents rather than actual strategic effects of airpower (which seem to be along the same lines as naval power: IE: A useful strategic tool but usually not in itself decisive unless the circumstances are very special)

I think a lot of ground troops would disagree that the war in the Pacific was won in the air. The American naval air arm certainly destroyed most of Japan’s navy, which made island-hopping easier, but the tightening noose of captured Japanese islands didn’t appear to shake their resolve any more than firebombing their cities did (and, as Brett says, the actual effect of the atom bombs on the Japanese decision to surrender is far from settled).

The point is, I think, that aircraft can’t occupy territory, and that the overwhelming success of American naval aviation in the Pacific war didn’t was largely in support of getting and keeping troops on the ground, capturing Japanese strongholds so they couldn’t be used against advancing Allied forces.

The issue with comparing bombing to blockades is that blockades have, historically, produced much stronger results. It’s legitimately hard to precisely detect the industrial impact of strategic bombing, but it is very ease to demonstrate the industrial impact of blockade on Germany (in either world war) or Japan.

Meanwhile, *carrier* aviation was crucial to the war in the Pacific, but principally against ships (against dug in ground forces, carrier aviation could struggle – promises of shore barrage and air attack clearing entrenched Japanese defenders again and again proved ephemeral), so what we’re really saving is that naval power – including a novel new way for ships to sink other ships – was crucial. Land-based airpower, by contrast, had real trouble sinking ships.

That last sentence should be land based *bombers* especially the two and four engined aircraft that were built for “strategic” bombing. (Although even here British four engined bombers sank a German battleship and three heavy cruisers in harbour late in WW2.)

Land based airpower sank an awful lot of ships and submarines in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, and among others British capital ships Prince of Wales and Repulse in the Pacific. However the overall point remains valid, in that these were aircraft and aircrews specialised for naval combat, not for operations over land.

The reason land based aviation often struggled against ships was that a lot of the land based aviation was *army* and thus had no proper training for anti-shipping strikes.

Contrary to what has been said about “bombers were designed for strategic attacks,” I am fairly certain that Anti-Shipping was explicitly one of the tasks the B-17 was supposed to perform and was supposedly designed to do. They merely drastically overestimated the ability of high-level heavy bombers to land *any* hits on a moving ship.