This week we’re looking at a specific visual motif common in TV and film: the arrow volley. You know the scene: the general readies his archers, he orders them to ‘draw!’ and then holds up his hand with that ‘wait for it’ gesture and then shouts ‘loose!’ (or worse yet, ‘fire!’) and all of the archers release at once, producing a giant cloud of arrows. And then those arrows hit the enemy, with whole ranks collapsing and wounded soldiers falling over everywhere.

And every part of that scene is wrong.

Now the thing that, in the last couple of decades, everyone has realized is wrong (I suspect some early Lindybeige videos had something to do with how widespread this notion is), is that you don’t tell archers to ‘fire’ because their weapons don’t involve any fire. But the solution in film has been to keep the arrow volleys – that is, the coordinated all-at-once shooting – and simply change the order to ‘release’ or ‘loose.’ Which isn’t actually any better!

Archers didn’t engage in coordinated all-at-once shooting (called ‘volley fire’), they did not shoot in volleys because there wouldn’t be any point to do so. Indeed, part of the reason there was such confusion over what a general is supposed to shout instead of ‘fire!’ is that historical tactical manuals don’t generally have commands for coordinated bow shooting because armies didn’t do coordinated bow shooting. Instead, archers generated a ‘hail’ or ‘rain’ (those are the typical metaphors) of arrows as each archer shot in their own best time.

More to the point, they could not shoot in volleys. And even if they had shot in volleys, those volleys wouldn’t produce anything like the impact we regularly see in film or TV. So this week, we’re going to walk through those considerations: briefly looking at what volley fire is for and why archers both wouldn’t and couldn’t do it, before taking a longer look at the problem of lethality in massed arrow fire.

But first, if you want to help support this project you can do so on Patreon! I don’t promise to use your money to buy myself more arms and armor, but I also don’t promise not to do that. And if you want updates whenever a new post appears, you can click below for email updates or follow me on Twitter (@BretDevereaux) and Bluesky (@bretdevereaux.bsky.social) and (less frequently) Mastodon (@bretdevereaux@historians.social) for updates when posts go live and my general musings; I have largely shifted over to Bluesky (I maintain some de minimis presence on Twitter), given that it has become a much better place for historical discussion than Twitter.

What Is Volley Fire For?

We want to start by understanding what volley fire is and what it is for. Put simply, ‘volley fire’ is the tactic of having a whole bunch of soldiers with ranged weapons (typically guns) fire in coordinated groups: sometimes with the entire unit all firing at once or with specific sub-components of the unit firing in coordinated fashion, as with the ‘counter-march.’ In both cases, the problem that volley fire is trying to overcome is slow weapon reload times: this is a solution for slow-firing but powerful ranged weapons. That has generally meant firearms, historically, but we do actually see volley fire drill with crossbows in China from a very early period as well (but, interestingly, there’s no evidence I am aware of that volley fire was ever done with crossbows in Europe – when Europeans decide to do volley fire with firearms, it seems to have been an entirely new idea).1

Volley fire can cover for the slow reload rate of guns or crossbows in two ways. The first are volley fire drills designed to ensure a continuous curtain of fire; the most famous of these is the ‘counter-march,’ a drill where arquebuses or muskets are deployed several ranks deep (as many as six). The front rank fires a volley (that is, they all fire together) and then rush to the back of their file to begin reloading, allowing the next rank to fire, and so on. By the time the last rank has fired, the whole formation has moved backwards slightly (thus ‘counter’ march) and the first rank has finished reloading and is ready to fire. The problem this is solving is the danger of an enemy, especially cavalry, crossing the entire effective range of the weapon in the long gap between shots. This, by the by, was the volley fire tactic that was being used in China with crossbows before gunpowder; I don’t know that anyone ever did volley-and-charge with crossbows, which lack the lethality of muskets.

The other classic use is volley-and-charge. Because firearms are very lethal but slow to reload, it could be very effective to march in close order right up to an enemy, dump a single volley by the entire unit into them to cause mass casualties and confusion and then immediately charge with pikes or bayonets to try to capitalize on the enemy being demoralized and confused. You can see variations on this tactic in things like the 17th century Highland Charge or the contemporary Swedish Gå–På (“go on”). By charging rather than waiting to reload, the attacker could take advantage of the high lethality of firearms without suffering the drawback of long reload times.

This is also not generally how we hear of gunpowder-based troops firing from a parapet like this: more often what we hear is that each file has a single shooter and several men behind him reloading muskets and handing them forward.

Crucially, note that volley-and-charge works because it compresses a lot of lethality into a very short time, which I suspect is why we don’t see it with bows or crossbows (but do see it with javelins, which may have shorter range and far fewer projectiles, but seem to have had higher lethality per projectile). As we’re going to see in a moment, the lethality of bows or crossbows against armored, shielded infantry – even in close order – was pretty low at any given moment and needed to add up over an extended period of shooting. By contrast, muskets were powerful enough to defeat most armor and thus to disable or kill basically anyone they hit, limited of course by reload time: with a reload time of as much as 30 seconds for earlier matchlocks, a line of musketeers might only be able to fire a few times at an advancing infantry unit (which might take two or three minutes to walk through effective range) and given the limited accuracy of smoothbore muskets, only the last shots would hit at a high level. By contrast, a unit doing volley-and-charge is compressing probably close to 50% of the lethality of sustained shooting, devastating moment and then immediately charging.

Putting that much lethality into a singular instant was valuable from a morale perspective and of course it enabled a unit to quick march through the enemy’s effective range, stopping only briefly to fire and charge, limiting losses from steady enemy fire. But as we’re going to see, the lethality of bows (and, to a significant extent, crossbows) was much lower and so couldn’t be effectively compressed into that single, devastating, confusing moment.2

Why They Wouldn’t and Why They Couldn’t

But as you’ve hopefully noted, these tactics are built around firearms with their long reload times: good soldiers might be able to reload a matchlock musket in 20-30 seconds or so. But traditional bows do not have this limitation: a good archer can put six or more arrows into the air in a minute (although doing so will exhaust the archer quite quickly), so there simply isn’t some large 30-second fire gap to cover over with these tactics. As a result volley fire doesn’t offer any advantages for traditional bow-users.

And so, as far as we can tell, organized volleys with bows weren’t done. We do have evidence in China for volley fire with crossbows, but of course crossbows, particularly more powerful ones, have all of the same reload-time problems that firearms do, so it is no shock to see the same tactics emerge. But historians have searched the ancient and medieval sources for any hint of volley fire with bows and have come up wanting. Now, I should caution here that this is a topic where if you are reading sources in translation you are likely to be fooled: many translators will use the word ‘volley’ to describe things happening in the original Greek or Latin or Old French or what have you that are not volley fire, for the same reason that filmmakers keep putting archer volley fire in their movies: volley fire is a big part of how we imagine warfare. But as hard as it is to prove a negative, I will note that I have never seen a clear instance of volley fire with bows in an original text and so far as I can tell, no other military historians have either. And we have been looking.

Of course the other reason we can be reasonably sure that ancient or medieval armies using traditional bows did not engage in volley fire is that they couldn’t. You will note in those movie scenes, that the commander invariably gives the order to ‘draw’ and then waits for the right moment before shouting ‘release!’ (or worse yet ‘fire!’). The thing is: how much energy does it take to hold that bow at ready? The key question here is the bow’s ‘draw’ or ‘pullback’ which is generally expressed in the pounds of force necessary to draw and hold the bow at full draw. Most prop bows have extremely low pulls to enable actors to manipulate them very easily; if you look closely, you can often see this because the bowstrings are under such little tension that they visibly sway and wobble as the bow is moved. This also helps a film production because it means that an arrow coming off of such a bow isn’t going to be moving all that fast and so is a lot less dangerous and easier to make ‘safe.’

But obviously actual bows are supposed to be dangerous.

And here folks will say, “ok, that’s prop bows, but I hold a hunting bow at full draw while lining up a shot all the time.” But there are two considerations here. The first is that many modern hunting bows are compound bows (note: compound, not composite), which is to say they use lever and pulley systems with wheels (‘cams’) which enable the energy at each stage of the bow’s draw to be controlled and are typically designed so that the energy necessary for the final bit of draw (that is, holding the bow at full draw) is relatively low. As a result, the strength required to hold a compound bow at full draw for an extended period is actually lower that what would be implied by its raw pullback.

But also the pullbacks of hunting bows are much lower than those of war bows. Modern hunting bows generally feature pullback weights around 40-60lbs (going higher for compound bows but still generally topping out around 75lbs and typically being much less) and shoot lighter, thinner arrows than war bows. And that should make a fair degree of sense: deer cannot shoot back and do not generally wear armor. The military archer, by contrast, needs a lot of lethality and a lot of range because he is shooting at someone with armor and weapons who means to shoot back (or run up and stab him), although as we’ll see, even with extremely powerful bows the ability of war archers to inflict lots of casualties is pretty limited against properly equipped enemies. If your hunting bow mortally wounds a deer but does not disable it, that’s not ideal but the deer is going to run away, not charge at you spear in hand.3

As a result, the pullback weights of war bows tend to be higher. How much higher? We’ve actually run through this evidence before: at least in Afroeurasia, as far as I can tell, 80lbs pullback is about as light as a war bow will usually get. Draw weights anywhere from 100lbs to as high as 170lbs (see Strickland and Hardy, The Great Warbow (2005) for details) are known for the highest end bows like the English longbow and Steppe recurve bows. Which is to say that the pullback weight range of ‘old world’ war bows exceed at their lowest end the heaviest common draw weights of hunting bows and keep going up dramatically from there. The typical war bow was more than twice as powerful as the typical modern hunting bow. These war bows shot with enough force that they required specialized arrows with thicker, more robust construction to withstand the amount of energy being imparted.

Which neatly answers why no one had their archers hold their bows at draw to synchronize fire: you’d exhaust your archers very quickly. Instead, war bow firing techniques tend to emphasize getting the arrow off of the string as quickly as possible: the bow is leveled on the target as the string is drawn and released basically immediately. Remember back to our statistic that a good archer can put around 6 arrows in the air in a minute? Well, even the best archer can’t do that for very long. I often see folks asking about how many arrows an archer could carry, seemingly imagining archers shooting at their maximum rate for prolonged periods (like they do in video games), but if you imagine pumping a 150lbs weight as fast as you can, I think you’ll immediately recognize that you aren’t going to be able to keep that up for more than a minute or two (more on this as well in Strickland and Hardy, The Great Warbow (2005), by the by). Holding the bow at draw for any length of time is going to accelerate that exhaustion and thus lower the rate at which shots are made and the time that rate can be maintained.

So the reason we have no evidence for archer volley fire is because they didn’t do it and they didn’t do it because it doesn’t solve a problem that exists with bows (whose rate of shot is fast enough not to require volley tactics) but it does cause all sorts of new problems (exhausting your archers).

But there’s a second related problem to these scenes: arrow lethality.

Modeling Arrow Lethality

Because when these arrow volleys arrive, the result is usually devastating, with large numbers of men falling all over the place (often being shot straight through their heavy armor).

But how lethal were arrow barrages? Well, the short answer is that we don’t know and it must have varied considerably. Teasing out the specific lethality of one part of an engagement from others is difficult even with modern warfare; for pre-modern warfare, we are often lucky to even have reliable estimates of total casualties in a battle, much less specific estimates of casualties caused by a specific source or weapon. Still, we have more than a few solid indications that the lethality of barrages of arrows, in some cases even over extended periods, could be quite low, which isn’t to say such weapons were ineffective.

We can start with ‘modeling,’ thinking through the question as a thought experiment (since we haven’t the expensive computer hardware and expertise to actually simulate it).4 Especially at long range, our archers are not shooting at individual enemies, but rather firing en masse into a large body of infantry, so we can assume shots are probably distributed fairly evenly in the target area. That’s already actually significant because as we discussed before, even in close-order infantry formations, there’s usually quite a lot of empty horizontal space (file width) where an arrow is simply going to hit…no one.

Depending on the way the men in the target infantry formation are facing and the formation, in most fighting formations, upwards of 50% of the total horizontal space simply doesn’t contain and humans to hit and arrows plunging into that space are going to hit nothing but the ground. Now the vertical space is trickier: there’s going to be a lot of empty space between the ranks as well, though we are almost never informed about how much. One exception is the Macedonian sarisa phalanx, where we’re told (Polyb. 18.29) that the sarisa of the fifth rank extends two cubits beyond the first rank, which lets us calculate roughly a 90cm rank interval. Other formations might have been tighter or looser, of course. But the implication here is that an arrow shot on a flat trajectory (so at very close range) at least half of the target area is entirely empty space; for an arrow shot in a high arc, as much as 75% of the target area might be. And of course in this estimation, we’ve been treating our soldiers like they are large rectangular prisms (our army of gelatinous cubes will be very effective), but of course actual humans aren’t going to physical occupy a lot of the space we’re even giving them here (note the silhouettes below). So the majority of arrows are simply going to miss.

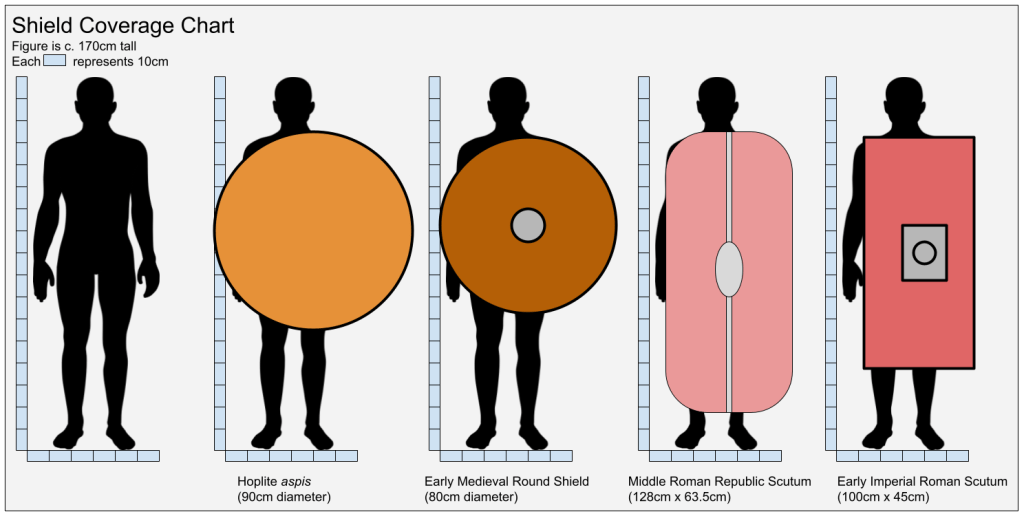

But of course then our target infantrymen are also not unprotected. Let’s assume here an average infantryman who is roughly 170cm in height (5ft 7in, a touch on the tall side, but not unreasonable for pre-modern agrarian soldiers). The first thing he is likely to have protecting him is a shield. For the purpose of our arrows killing or disabling our infantryman, a decent shield is essentially perfect protection in the area it covers: even very light shields can ‘catch’ arrows effectively (and indeed, this is what very thin hide or wicker shields are for). The one risk we face is the arrow punching through the shield into the shield arm, which could certainly happen, but many shields have reinforced metal bosses over where they are gripped, making this less likely. But as we discussed with shield walls, shields often cover quite a lot of the body; shields could be quite big. So let’s draw that out with some example shields, to scale with a human silhouette (again, 170cm tall) and see how much of this relatively big fellow (by pre-modern standards) typical shields covered:

What you can immediately see is that just about any shield is going to massively reduce the target area of the body even if it isn’t moved. All of these shields are large enough to cover the entire trunk of the body, protecting all of the vital organs in the torso. Assuming our infantryman has crouched down a little and put his shoulder into his shield (and kept his weapon hand behind it), our archer has lost upwards of three-quarters of his target area (even higher for very large shields like the Roman scutum). Worse yet, the target area that remains is mostly legs where arrow strikes, while painful, are a lot less likely to be lethal and may not even be disabling.

And of course these soldiers can move their shields, angling them up if the arrows are plunging downward or crouching behind the shield if they’re arriving on flat trajectories. Moreover arrows at range move slowly enough to be actively blocked and dodged, to the point that we know that ‘arrow dodging’ was a martial skill of some import in cultures that engaged in small-scale bow exchanges as part of ‘first system‘ warfare.5 Of course, if the incoming hail of arrows is dense enough, soldiers might be unwilling to put their heads up to try to spot incoming and block (at Agincourt we’re told the French soldiers angled their helmets into the arrow-rain, for instance), but infantry under lighter ‘fire’ might actively move their shield to block specific incoming arrows.

And then behind that shield our infantryman is also probably wearing some kind of armor! Now a full plate harness is going to provide only extremely few points of vulnerability, but to give our archers a more favorable case, let’s stay in the ancient world and consider two ‘edge’ cases from the Hellenistic period: a mailed Roman legionary (the most heavily armored infantryman of the period) and a Gallic warrior (one of the less armored infantrymen of the period). By picking soldiers this early, we’ve given our archers a bit of a hand: these fellows don’t have fully enclosed helmets, or significant arm protection; later medieval combatants, particularly with wealth, would have been much better protected, with things like aventails to cover the neck and fuller protections for arms and legs. The Roman has a mail lorica hamata, a Montefortino-type helmet (with cheek-flaps protecting much of the face) and greaves, while our Gaul has just the helmet and probably some thickened textile body protection. The coverage might look like this (please forgive my very rough efforts to draw out irregular shapes):

Now as we’ve discussed, armor protection against arrows isn’t necessarily a binary. Armor often gets discussed as if arrows either always defeat it or never do and really only one of those is correct: arrows will not defeat good iron or steel plate armor at effectively any range. But for other forms of armor, the range and the power of the bow matter a lot. I’m going to summarize my previous estimates here (but I sure do wish we had more long-range bow-penetration testing!): at relatively long range (c. 200m) even powerful bows might struggle to reach the target with enough impact energy to penetrate mail and relatively weak war bows – which are still bows with 80lbs pullback (so our weak war bow is roughly 50% more powerful as a typical hunting bow) – may struggle to even penetrate a good textile defense with a solid hit. Even at moderate ranges (c. 100m), mail will probably sometimes defeat even the most powerful bows (but sometimes it will fail) and even a gambeson provides a degree of protection from the weakest (again, still 80lbs pullback bows).6

What that means for our Roman legionary up there the good news is that very few arrows are going to accomplish much; the situation is worse for our Gaul, but actually not much worse. For the Roman legionary, he has upwards of 85% of his body covered by his giant shield. Should an arrow get around that shield somehow, to hit anything vital (except his face) it has to contend with his mail. Now powerful war bows, especially at short range can absolutely defeat mail, but not every shot is going to be the most powerful bow shooting a point-blank range shot hitting dead on and for the rest, a decent chunk of them are going to fail to split the mail rings or else expend so much energy doing so that they don’t penetrate lethally deep through the thick textile padding (the subarmalis) beneath the mail. Meanwhile, his lower legs below the shield are covered with solid bronze greaves which will almost always deflect an incoming arrow (they’re both solid metal, but also curved so an arrow is likely to glance off). His head and neck remain the big point of vulnerability, but something like three quarters of that space is covered by his helmet and his cheek-guards: an arrow slamming into a solid, 1.5kg bronze helmet is going to be unpleasant, but the arrow isn’t usually going to penetrate (though the impact may daze or even knock out the soldier).7

And if we start stacking these ‘filters’ for our arrows, we see the lethality of our barrage drops very fast against infantry. Maybe two-third to three quarters of our arrows just miss entirely, hitting the ground, shot long over the whole formation and so on. Of the remainder, another three-quarters at least (probably an even higher proportion, to be honest) are striking shields. Of the remainder, we might suppose another three-quarters or so are striking helmets or other fairly solid armor like greaves: these hurt, but probably won’t kill or disable. Of the remainder, a portion – probably a small portion, because of those big shields – are being defeated by body armor that they could, under ideal circumstances, defeat. And of the remainder that actually penetrate a human on the other side, maybe another two-thirds are doing so in the arms, feet or lower legs, many of them with glancing hits: painful, but not immediately fatal and in some cases potentially not even disabling.

After all of those filters, we’re down to an estimated arrow lethality rate hovering 0.5-1%, meaning each arrow shot has something like a 1-in-100 or 1-in-200 chance to kill or disable an enemy.8 To put that in perspective with the images above: Aragorn’s book-inaccurate Elf allies (about five hundred of them) could all shoot over the whole approach (probably about a minute) and kill or disable about 25 Uruk-hai out of that host of ten thousand.9

Of course they wouldn’t be firing in volleys and numbers would matter. But we can extend our model a bit. Let’s assume an equal sized force of heavy infantry, advancing at the quick step (so a march, not a charge) against an equal sized force of archers. Bow shot is about 200m, which a quick march will cross in about 2-and-a-quarter minutes (quick step is 120 steps per minute, 75cm covered per step, roughly). Each archer can loose six arrows a minute, so each infantryman has, on average, 13.5 arrows to deal with. His chance of being killed or disabled by one of those arrows over the course of marching into contact (assuming our 0.5% arrow lethality) is thus about 6.75%. And that is under very favorable assumptions for our archers: our infantry doesn’t break into a charge, has no screening forces, the archers can shoot at maximum effective range, don’t tire out their arms and can all shoot effectively for the entire period (no return shots, no being blocked by friendly troops, etc). In practice, we should probably also impose a pretty sharp lethality ramp for these arrows: our 0.5% lethality figure is based on arrows loosed at pretty close range on flat trajectories, but of course the earliest shots in this scenario would be at much longer range, with less power and accuracy and so much less lethal; our 6.75% figure is thus something of a maximum. A 6.75% ideal disable rate is not going to stop the determined advance of heavy infantry: that infantry is going to march right on into contact and if those archers don’t have their own heavy infantry to meet it, they are going to be put to flight very quickly.

The Model and the Metal

Now if all we had was modeling, this sort of analysis would be shaky, because we’re making so many simplifying assumptions. But of course we now want to compare our model with actual battles to see if it seems like it is describing their mechanics accurately. At the Battle of Marathon (490 BC), a force of 10,000 Athenian and Plataean hoplites advanced over open ground into contact with a larger force (perhaps roughly double) of Persian soldiers, most of whom were likely archers, given how the Achaemenid army fought: the Athenian-Plataean army charged into contact and routed their enemy with just 192 KIA; many of these losses moreover were not from arrows, as our best source, Herodotus, is clear that the hardest fighting was in contact at the ships.10 At Issus (333BC), Alexander orders a quick approach for his infantry, worried about the large numbers of Persian archers (Arr. Anab. 2.10.3), but the Macedonians reached the Persian line and in the whole battle reportedly sustained only 150 killed, 4,500 wounded (Curt. 3.11.27). At the Siege of Nicaea (1097 AD) the relief army of Kilij Arslan, composed primarily of Turkish horse archers – some of the finest and most dangerous archers around – attempted to move the crusader shield wall but was unable to do so despite a prolonged effort (he eventually gets pulled into contact with heavy crusader cavalry and is quite soundly defeated).

And then, of course, there is Agincourt (1415 AD). On the one hand, Agincourt is held up as the great example of the victorious power of the English longbow. On the other hand, both the initial French cavalry charge and the subsequent French infantry advance were able to cross a muddy, open field into contact with the English force.11 Agincourt reflects, in many ways, an ideal battle for the English longbow: the enemy was forced to advance the full range of the weapon, without cover, over difficult ground and did so in distinct ‘waves’ (the French army was deployed in three successive lines), on a battlefield where the forests ‘canalized’ (funneled into a narrow space) the French advance and secured the English flanks. And yet under these conditions the French infantry were able to cross the terrain in good order and attempt to breach the English line. Of course, despite outnumbering the English, the French infantry attack was too weakened by the arrows to overcome the English men at arms and archers in contact and so the English won a great victory.

But the nature of that victory is actually quite telling: even in ideal circumstances, with one of the most powerful bows in history (and a body of experienced archers to wield them) the English could not simply ‘mow down’ the incoming infantry attack slogging forward. But at the same time, the continuous rain of arrows created the conditions for the English to win in the press of melee despite being outnumbered. The Roman historian Livy has these phrases that always jump to mind in these situations, describing men or armies – often still very much alive – as fessus vulneribus or vulneribus confectus, “tired/worn-out by wounds” (Livy 1.25.11; 22.49.5; 24.26.14). After all, an arrow that gives a shallow cut glancing off an arm or bangs off a helmet or other piece of armor or slams into a shield isn’t going to kill you and probably isn’t immediately disabling, but it does hurt and the added impact of cuts and bruises is going to contribute to exhaustion (and arrows stuck in a shield make it harder to wield), slowly but steadily diminishing the fighting capability of the recipient.

That is how I would understand the failure of the French infantry advance at Agincourt. It isn’t that the longbows killed them all, but that they injured, exhausted, confused and disconcerted the advancing infantry, so that by the time the French reached the fresh, close-ordered and prepared ranks of the English, they were at a substantial disadvantage in the close combat.

Now since I have brought up Agincourt, we also want to talk about cavalry. Because so far, we’ve been focused on infantry facing massed archery. But note that at battles like Crécy (1346) and Agincourt (1415), the French also try cavalry charges and in both battles, these are very roughly repulsed.12 That may seem strange because in strategy games and the like, cavalry is the solution to archers, able to close the distance and defeat them quickly.

But actual battles are more complicated. On the one hand, cavalry is faster: even heavy cavalry can cut the time spent crossing the ‘beaten zone’ of bowshot from around 2.5 minutes to just 1 minute. On the other hand, horses are big and react poorly to being wounded: a solid arrow hit on a horse is very likely to disable both horse and rider. And while light or archer cavalry might limit exposure to mass arrow fire by attacking in looser formation, as we’ve discussed, European heavy horse generally engages in very tight lines of armored men and horses in order to maximize the fear and power of their impact. Unsurprisingly then, we see from antiquity forward, efforts to armor or protect horses, called ‘barding’: defenses of thick textile, scale, lamellar, and even plate are known in various periods, though of course the more armor placed on the horse, the larger and stronger it needs to be and the slower it moves. Nevertheless, the size and shape of a horse makes it harder to armor than a human and you simply cannot achieve a level of protection for a horse that is going to match a heavy infantryman on the ground, especially if the latter has a large shield.

Finally, the other thing about cavalry is that they weren’t as numerous. The cavalry charge at Agincourt had in it only 800 horsemen, for instance.13 But horses are big and cavalry cannot be packed in a deep formation, for reasons we’ve discussed, so the cavalry would still take up a fair bit of space on the battlefield, meaning that they would draw shots from a lot of archers, potentially overwhelming the advantage of covering the space more rapidly. Michael Livingston, op cit, does his own modeled simulation of the longbow impact on the French cavalry charge, with a lethality ramp from 0.25% to 2% over the charge and estimates that well over half of the riders wouldn’t have made it to the English lines.14 With so many archers firing at so few horsemen, the imbalance quickly produces catastrophe, although it is worth noting that even at this point the French cavalry charge did reach the English line, albeit without the numbers or the morale impact to overcome it, with French knights being pulled off of their horses within the English infantry formation, having presumably slammed through in their initial impact.

Conclusions

One of the challenges in understanding pre-modern warfare is in navigating between the extremes of ‘wonder weapons’ and ‘useless’ weapons. If bows were so powerful that they could mow down heavy infantry or invalidate cavalry, no one would have fought any other way. We know that, of course, because eventually a technology emerges – firearms – which was so lethal that it steadily pushed every other way of fighting off of the battlefield, save for a bit of light cavalry. Bows and crossbows existed for far longer and didn’t have this effect, because they weren’t that powerful: they simply lacked the tremendous lethality of firearms. The very strongest war bows might deliver at most around 130 joules of impact energy, slicing and piercing through a target. By contrast even relatively early (16th century, for instance) muskets could deliver one to two thousand joules of impact energy, with a projectile that didn’t neatly slice or pierce the target (it didn’t need too), but smashed through, shattering bone and shredding issue over a much larger area.

At the same time, bows and crossbows obviously weren’t useless. Of course for nomadic steppe-based armies, they were the primary weapon and rapidly maneuvering horse archers could use bows to devastating effect (in part because unlike foot archers, they could repeatedly caracole into that higher lethality zone at very short range). For agrarian armies, archers and other ‘missile’ troops could screen heavy infantry or cavalry, harass enemies and under the right circumstances degrade an enemy force quite heavily, even if they couldn’t simply ‘mow down’ advancing infantry. To counter this, more sophisticated armies might advance their close-order heavy infantry with screening forces of light infantry, often with looser spacing (thus lowering the incoming arrow ‘hit rate’ even further). The Roman legion of the Middle Republic had a built-in screening force, the velites, while we see the French, particularly at Crécy, attempting (and failing) to use their crossbows in this way. Those screening forces existed in part because harassing ‘fire’ from missile troops, while it might not turn back the advance of a legion, could significantly hamper it and so it was worth tasking a significant portion of the army to preventing that (and harassing the enemy in turn).

Of course TV and filmmakers are not thinking in these terms, but instead deploying – often without much thought – a set of visual tropes for battles which all have their origins in warfare in the gunpowder period. Directors love, for instance, having characters hold each other at bow or crossbow point, something that makes sense with modern firearms, but not with bows or crossbows (if you had to hold someone at weapon-point in the pre-gunpowder world, you used a sword or a spear).

The visual film ‘language’ for ranged engagements, in turn is very clearly drawn from warfare in the 1700s and 1800s. I suspect we can actually be a lot more specific, with the touchstones here being the American Revolutionary War and the American Civil War. Film as a genre, after all, emerged and was in its early days substantially shaped in an American context and much of filmic language remains dominated by Hollywood and in the United States, reenactments of ARW and ACW battles are quite common and for many movie-makers would be the primary way of engaging with any kind of warfare before the emergence of the genre of film itself in the early 1900s. This, of course, introduces some of its own problems even for the warfare of the 1700s and 1800s, as reenactments tend to recreate parade-ground and field manual maneuvers and impose them on battles that were probably quite a bit more fluid and disorganized, but that’s a question for other scholars, I think, to unpack.15

But that mental model of warfare imposes both a physical logic and a dramatic logic on to battle scenes set in pre-gunpowder societies which simply do not belong there: the most obvious being the hero-commander dramatically giving the order to ‘fire’ at the key moment, something that calls back to the mythology around “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes,” but which is inappropriate for bows and crossbows, which – among other things – we know often began slow shooting right at maximum range.

As with our discussion of “The Battlefield After the Battle,” I think there’s an opportunity here for filmmakers to break with that tradition and attempt to show the view a meticulously reconstructed battle and reap the dramatic benefits of how interesting and alien that would be. But until then, I suppose, I will have to suffer through more films showing archers doing volley fire drills, while kings shout for the men to ‘fire!’ their bows.

- On drill and in particular, counter-march volley fire with crossbows, see Andrade, The Gunpowder Age (2016), 149-160.

- It also didn’t generate a smokescreen to help with the final rushing charge, whereas a musket-and-bayonet unit might benefit significantly from firing and then charging through and out of its own obscuring smoke into a terrified and confused enemy.

- And for animals that might do so, there’s a reason that for hunting something like a boar there were specialized spears to deal with an angry charging one.

- This, it seems to me, should be possible with modern technology, to simulate each arrow’s physics reasonably accurately, but history research is almost never so well funded as to be able to do that kind of work and right now the federal funding for history research, the National Endowment for the Humanities, is facing cuts and possible extinction, rather than being expanded.

- On arrow dodging in a Native North American context, see Lee, “The Military Revolution of Native North America: Firearms, Forts and Polities” in Empires and Indigenes, (2011), 58, fn. 34.

- That said, even for a fellow with full plate protection, there are points of vulnerability: not every component is as thick as the breastplate, but the big worry are the eye-slits and breaths (breathing holes) in the visor. These are generally small enough that an arrow can’t get through whole, but an arrow striking one might shatter, sending deadly or debilitating sharp splinters through. Note, for instance, these experiments by Tod Todeschini.

- Roman helmets, like medieval helmets, were worn with padded textile liners, which would absorb some of the impact, but an 50-80 joule head impact is still going to hurt quite a lot!

- 100 * 0.25 (miss) * 0.25 (shields) * 0.25 (helmets, greaves) * 0.33 (non-disabling hits (arms, legs, feet) = 0.52%

- Of course the effectiveness of bows in sieges is that attackers looking to set ladders or scale walls are going to need to be vulnerable for a lot longer and a well-defined fortification is going to enable ‘enfilade’ fire (shots coming from the sides, via projecting towers), all of which means the attackers have to sit in that higher lethality point-blank-range zone for a lot longer.

- Hdt. 6.114-117. I have seen online many times the figure of 11 dead for the Plataeans cited to Hdt 6.117, but the figure is not there in the passage and I do not know where it is from.

- On the battle, a good and readable primer is M. Livingston, Agincourt: Battle of the Scarred King (2023).

- I want to note, because we’re trying to see how archers work when everything is going well, we’re focusing on English victories, but English longbowmen did not always win their battles either: sometimes the French infantry and cavalry were able to close the gap and win, as for instance at Formigny (1450). For the longbowmen to succeed, they needed quite a lot to go right for them.

- Livingston, op cit, 253

- I will note that Livingston breaks this simulation into ‘volleys,’ but I don’t think he means they’re actually firing in volleys (they don’t seem to have been, the sources describe ‘clouds’ and ‘hail’ of arrows, implying continuous shooting), it’s just a useful set of mathematical divisions to break his lethality ramp into.

- But consider reading Spring, With Zeal and With Bayonets Only: The British Army on Campaign in North America, 1775-1783 (2008). I also have with me, but haven’t yet read, but have very high hopes for A. S. Burns, Infantry in Battle: 1733 – 1783 (2025), so we might return to this topic at a later date.

A first synchronized volley, with “release at will” afterwards, strikes me as a reasonable approach. You get a significant moral shock waiting for and then seeing that cloud of arrows, and that initial volley would likely mess up front ranks, causing confusion and slowing down the subsequent ranks.

You wouldn’t get a “cloud of arrows”, there were never enough archers in a given army to fire that many arrows at once. And as Bret explains, arrows don’t have a high enough kill rate to “mess up the front ranks.” Arrow fire was an attritional tactic–it had it’s effect over time.

Still way overestimating the power of arrows to quickly mass-kill or mass-disable. An “initial volley,” taking place over a few seconds, simply isn’t going to “mess up front ranks” to the degree where you have the luxury to shift your focus to thinking about “slowing down the subsequent ranks,” with release at will, as if the front ranks themselves are now out of the picture. They aren’t.

Inflicting enough arrow casualties to render ranks of heavy infantry, equipped with armor and shields, combat ineffective would have been painfully slow work, even if your own archers were shooting unopposed and untroubled by return missiles and free to come up to relatively close range. It simply was not the work of a single initial volley. Not even of a few minutes’ worth of unharassed shooting. It was in many cases the work of hours, or in a few cases, multiple days.

The first volley would be when the enemy is just getting into range at which point it would be least effective. If you wait until the volley would be effective, then you’re just letting the enemy advance for free, which is a heavy cost for an uncertain payoff.

I just wanna say most people nowadays never shoot even 1 arrow. If any one have years of training and actually have shot a hundred pounds bow they won’t think arrow and bows do less damage compared to javeil or early rifles.

> You know the scene: the general readies his archers, he orders them to ‘draw!’ and then holds up his hand with that ‘wait for it’ gesture and then shouts ‘loose!’ (or worse yet, ‘fire!’)

Why is that worse? I could see the complaint if you were watching a film about 14th-century English longbowmen that had all the dialog in Middle English, though I doubt that film would get made.

But in the example image, I assume that if Darius III gave a command to his archers, he gave it in Old Persian. The movie dialog is translated into English for our benefit. And ‘fire’ is normal modern English for that command.

The pedantic point is that “fire” is a command specific to gunpowder weapons. You don’t fire a bow, you loose it or shoot it.

But that’s simply untrue. It’s a command for anything that has a notionally instantaneous release. Merriam-Webster cites it being used for punches. Intransitive sense 3(b) is, in full: “to emit or let fly an object”.

The pedantic response is that this is a usage which arises by analogy to discharging a firearm. Now we fire off a punch or an email precisely to evoke the connotations of firing a gun. This is pretty well attested in the etymology.

Sure, but I think Michael’s point is that as soon as they’re speaking in modern English we’ve swallowed an enourmous anachronism, and to strain at the gnat of one particular word being used in its modern English sense is an isolated demand for rigour, that smells more of trying to show off our knowledge of one bit of etemology than a principled commitment to realistic period language.

Except that this particular anachronism actually does jar many viewers, probably because it is technological as opposed to cultural. Most people don’t know (for example) how Roman names worked, so “Maximus Decimus Brutus” doesn’t bother them, but they know that the Romans didn’t have guns, and a decent number of them think it through and see that “fire” makes no sense as a command to shoot.

I suppose it’s

Good luck pulling a medieval long bow 6 times per minute 🙂

Joe Gibbs can do it in half that time:

https://youtu.be/1w8yHeF4KRk?si=lPfI-ndIY1PHs4A_

Modern people who can are extremely rare. Much like present-day sports stars, pre-modern archers would begin regular practice while their bodies were still growing, which was known to make a difference.

It’s rare because there are no incentives to do so today. Modern people _can_ build up the strength to shoot with 120-140lbs. war bows in maybe three or four years, starting in adulthood, if they didn’t have to work full-time and somebody were paying them to practice every other day instead. The people who manage to reach that level under those circumstances wouldn’t be that rare, maybe more like college-level amateur athletes or adult Crossfit members rather than high-level professional sport stars.

It’s probably far from unachievable _in the first minute_ for the elite English archers picked and hired for French campaigns. Remember, these were the highest-performing minority among all the “middle class” Englishmen who could afford the free time to practice archery, and we know that the rest of the archers left back home were generally not as good — Gutierrez Diaz de Gamez’ accounts of Franco-Spanish raids on English coasts mentioned crossbowmen outshooting local defence militias’ archers on several occasions, while Commissions of Array during the Wars of the Roses often had to recruit archers with somewhat less discrimination (in the older, positive sense of the word) and produced forces that were notably less efficient than more professional archers. And those professional archers getting six, eight, or even ten arrows out in a mad minute, especially if they didn’t have to keep it up into a second or third minute? Hardly unthinkable.

I thought Peter Wilson had an interesting point that it’s not *just* the appearance of firearms that brought about volley fire (arquebusiers in Spanish terzios fired in their own time), you also had to have a philosophical change to allow seeing a human as a cog in a larger machine; it’s fundamentally an Early Modern concept rather than a renaissance one. And so you first see volley fire among the Italian condottieri and the Low Countries’ militias, where you were simultaneously seeing the start of mercantile economies based on transactions between individuals.

How do you reconcile that with the ancient Chinese crossbow volleys?

Volleying is a technology; you use it if it’s beneficial, and not otherwise. You obviously do not need to hold any particular philosophy to do so.

I would say that the view of humans as replaceable cogs in a larger machine may not have been alien to ancient Chinese thought? Whereas that view was in conflict with Renaissance European humanism.

I failed to see how using a better shooting technique for your troops contrasted with humanism, compared to the pike column – a clearly Renaissance invention which required a lot of “cogs in the machine” to function (by the ways all types of volley fires invented during the 17 century – still in the Renaissance, and yes, Italia and the Low Countries were centers of the Renaissance).

Not to mention that well-drilled Roman legionary infantry were certainly “cogs in a machine.” They fought in formation (albeit more flexible than the hoplite phalanx) and were trained in tactical maneuvers. They didn’t fight as a bunch of individuals, such as Norse berserkers, for example.

I would actually resist a description of Roman soldiers (or most any soldiers) as simply ‘cogs in the machine.’ The Roman oath, for instance, permits a soldier to leave his post in a formation to strike an enemy or recover a weapon, and so assumes significant individual initiative, a pattern we see in our sources as well: initiative within the bounds of disciplina.

Not clockwork soldiers. More on this point to come in a week or two when I discuss Alex Burn’s book.

“so assumes significant individual initiative”

But would you guess that that assumption of initiative would conflict with training Romans to do a countermarch crossbow volley?

“had to have a philosophical change… it’s fundamentally an Early Modern concept”

Chinese texts describe crossbow volleys (via rotating crossbowmen) back in the Han Dynasty, 169 BC. A 759 AD Tang text has illustrations of the maneuver. Japan was doing firearm volleys in the late 1500s, not that long after acquiring firearms at all; Korea was doing it by the early 1600s, in response to Japanese invasion.

So I’m rather skeptical of this claim of ‘philosophy’ rooted in a limited period of European history.

I’m not sure I follow you; different times and places have different worldviews. A philosophical limitation that impacted Renaissance Europe isn’t particularly relevant to 8th century BC China or 17th century Korea.

“A philosophical limitation that impacted Renaissance Europe”

I am basically unconvinced that there is any such philosophical limitation relevant to the creation of firearm volleys. It sounds like a poorly-supported Just-So story.

To me it feels more plausible that early guns were a continuation of archery tradition so it would begin with gunmen shooting at their own pace. Volley fire was then a later innovation. It might have started with a single gunman trying to fire his first shot after several of his companions had already fired and realizing that he can’t see his target, and suggesting to do a simultaneous first shot the next time. They would probably witness the other benefits of volley fire soon. Of course when the unit is equipped with enough firearms to have several ranks of shooters volley fire becomes practical necessity.

With the crossbow volley fire being an ancient Chinese invention the Japanese and Koreans would have undoubtedly been familiar with the concept, so a gunpowder volley fire would probably be an obvious choice for them and not even a new invention.

Pikemen are “cogs in a bigger machine”, even if the period wouldn’t have used those words to describe it. For that matter, Roman milites and Greek hoplites are also “cogs in a bigger machine”.

*Someone* in the West figured out that splitting your firearms into groups and delivering “fire by platoons”, as it eventually became, was more effective than everyone firing in their own time, just as someone in China figured out the same for crossbows (though apparently, the West never did the same).

Your blog is so fun to read. It pops up on hacker news now and then and the content is so entertaining. Thank you

Great article! Now I, as a sports/hunter archer, can send a link to explain why volley fire is stupid instead of trying to do it myself.

Other stupid things from movies and videogames:

– Arrows always pierce plate mail like it was made from paper.

– However, arrows never go trough unarmored humans (or zombies), they always get stuck (in reality, unless it hit a bone, the arrow most probably will go trough the body cleanly).

– (This one is mostly from videogames where you can sometimes recover the arrows): 90% of the time, arrows break on impact (in reality, unless they hit something really hard like a brick or a stone, they most of the time don’t break).

The only videogames that do archery right are the Kingdom Come Deliverance ones!

Arrows passing through the body at least seems to be complicated by the use of barbed arrowheads intended to become embedded in flesh, and it is my understanding that there are historical references to recovery of arrows.

Barbed arrowheads aren’t really intended to become stuck in flesh. Rather they serve two purposes:

1. They make a wider cutting surface that does much more damage to the target (this is why they’re ubiquitous in hunting) with a minimum of weight.

2. If the arrow hits bone or armour or something that causes it to get stuck, removing one is much harder.

“2. If the arrow hits bone or armour or something that causes it to get stuck, removing one is much harder.” Henry V certainly knew this from direct experience! https://www.medievalists.net/2023/08/prince-hal-head-wound/

Not sure about barbed heads since I never hunted with these, I use triple broadheads like these (https://shorturl.at/wc3bE) which are designed to maximize bleeding so the animal lose consciousness quickly, and unless you hit a bone, the usually go clean trough the animal (which is better for hunting since with an exit hole there will be more bleeding = less time for the animal to lose consciousness).

“arrows never go trough unarmored humans (or zombies), they always get stuck (in reality, unless it hit a bone, the arrow most probably will go trough the body cleanly).”

That was new to me, I always thought arrows get stuck in the flesh of the victim. The only time I recall seeing an arrow go clean through in cinema/television was in LOTR/FOTR-one of Legolas’s arrows goes through an orc and gets stuck on the wall (or tree) behind. I thought it was meant to suggest the superhuman bow skills of an elf, but apparently it was one of the few realistic depictions of archery!

This is a case where talking to modern bow hunters can provide a lot of insight. Unlike a soft-point bullet that strikes with such force that the lead will deform during impact with the body, ‘wasting’ some energy and making the process of “pushing” through the body more difficult, an arrow hitting tissue is much slower, will not be permanently deformed (unless it hits particularly thick bone), and has a very efficient cutting surface. So it is common to read of modern bow hunters shooting straight through one flank of an animal and out the other, even at relatively modest hunting poundages—there’s no need to add 100+ lbs of draw weight and cause arm jitters; what’s instead preferred is to take a careful, very precise shot to a ~6″ diameter circle from fairly close range to cleanly take down a game animal with a shot through the heart-lung area (other hits may eventually be fatal but if the animal’s trail is lost in the meantime that’s of little comfort to the hunter). Yet that same arrow would be ‘caught’ by loosely hanging a carpet or rug aloft, something even the weakest firearm would have zero problem zipping right through. Penetration physics is funny like that!

Again… as we are dealing with Pedantry… and not really that as it’s a techical term…

You don’t fire bows, whether hand or cross bows.

The term we use comes from giving fire, which was the order given with early firearms,

With bows you shoot or loose.

And even with firearms, it is still called shoot, as shouting fire on flammable age age of sail ships, and where fire was so dangerous, wasnt a wise idea

Here’s a neat comparison. The article considers an impact to the head with 80J of energy, and says the strongest war bows top out around 130J of delivered energy… A regulation baseball has about 145g mass. The equation for kinetic energy is KE = 1/2 * (Mass) * (Velocity)^2

A baseball with 80J of kinetic energy is traveling about 33m/s, or 74 mph, which is about the average speed of a high school pitcher’s fastball. A baseball with 130J of kinetic energy is traveling about 42 m/s, or 93 mph, which is about the average speed of a major league fastball.

Of course a MLB pitcher is a prime athlete who, I assume, would be more physically capable than your average bowman. But it’s remarkable to see that they’re able to impart the same energy to a projectile as the heaviest war bows. It makes me wonder if anyone has studied how much mechanical advantage a bow gives to its wielder – comparing a bow and a javelin throw, how much additional energy can be imparted through the use of a bow? Or are they really comparable in terms of imparting energy, and the bow is just a more efficient way to get all that energy into a smaller projectile like an arrow?

And for anyone wondering what it might feel like to stop an arrow with your shield, or armor plate, or helmet, just find your local pitcher and ask them to do you a favor.

Humans are really good at throwing stuff. Really really good at it. What a bow gives you over a javelin is _velocity_, not energy.

Your MLB fastball has ~40m/s of “muzzle” velocity.

A modern sporting javelin tops out at about 30m/s for men (800g projectile weight). A heavier fighting javelin will be proportionally slower.

A longbow arrow is more like 60-70m/s.

You can bump up even higher with lightweight flight arrows and composite bows, although you’ll be losing energy by doing so (all other things being equal, a heavier arrow is more efficient at taking the energy stored in a bow).

This is important because velocity means range. Gravity acts on all projectiles at the same speed, so the faster it’s going the farther it can get before it falls out of the sky.

Conversely, energy and momentum are what actually kill people. The javelin is the hardest hitting personal ranged weapon until pretty much the invention of the gun.

“What a bow gives you over a javelin is _velocity_, not energy.”

The other consideration is the size of the area of impact. What causes damage isn’t energy, it’s stress–really, pressure. You can run over someone’s foot with an excavator and it’s fine; stomp on their foot with a stelletto heel and they’re taking a trip to the emergency room and unable to walk for a while (my Structural Geology professor had us do the calculations). Likewise, if you get hit with a baseball, the surface of impact is going to be significantly higher than the surface of impact for an arrow with a sharp point. A baseball doesn’t seem huge, but you’ve got to remember that a sharp point can be measured in microns; that means that a baseball is going to impart 8-10 orders of magnitude less stress on the human body than an arrow.

There have been measurements of longbow arrows that hit 140+ J, and some of the heavier Manchu bows were probably pushing 200 J or even higher.

The other thing that complicates this is that you also need to get the momentum relatively close. A small, fast projectile with relatively little momentum isn’t going to feel the same as a slower, heavier one, even if they both have the same kinetic energy.

The additional energy imparted to an arrow by the bow is zero. Any energy transferred to the arrow comes from the archer’s muscles.

We know this because there is no breakdown of the bow (or there shouldn’t be!) to provide any extra energy.

So it’s not surprising that the pitcher is able to put about as much energy into the baseball as an archer can put into an arrow. The ball is an efficient shape for energy transfer to the ball, while throwing an arrow would not work as well. The bow allows for more efficient throwing as it were.

Firearms work differently because the energy comes from the combustion of the propellant. Not only does it not exhaust the energy of the user’s muscles (or only for control) but this allows for much more energy to be imparted than muscles could possibly provide.

A bow stores and releases energy, and uses a different set of muscles. So it could, in theory, store more energy for a single arrow then a single throw could give any particular object. And, by using a different set of muscles, and different set of forces, tire out a person less then an equivalent throw would do.

Regular bows and arrows don’t seem to actually do this based on the results of testing, but crossbows of various sorts seem to get more energy, not to mention muscle powered siege engines.

Bows are also a type of lever in that the speed of discharge is much higher than the speed of the draw.

An archer volley is how you throw shade on the Spartans.

Why can’t you hold someone at crossbow point? Light crossbows aren’t hard to hold steady and they latch the arrow for you so they can be fired by trigger.

Same reason you can’t hold someone at gunpoint. You can, only if they allow you do. If someone wants to take a chance they just wait for a moment when you are not paying enough attention and jump out of the way of the gun and start throwing punches. If they have even a little surprise they are out of the line of fire before you can pull the trigger and from there you just keep hitting their arm away so they can’t get you. You are taking a big risk because they have a gun: if you fail to get surprise, or you let them get the gun pointed at you – you are dead. A pistol is generally going to be easier than a crossbow if you are holding it in a fist fight, but either way both are useless in a close fist fight except via luck.

Note that police rarely hold someone at gunpoint in the real world (if ever), that is for the movies. They use their baton, handcuffs, or other means to secure the suspect that work. A loaded gun pointed at someone has too high a likely hood of going off to risk pointing it at anyone you are not serious about killing. Either you are serious: pull the trigger, or you are not serious: so you shouldn’t have the gun drawn in the first place.

Ok, but the same is true for e.g. a spear, which Brett mentioned in the post as a real-world example of a weapon at the point of which one can be held. But if you wait until they are distracted, or just take some luck, you could bat the tip out of the way, or grab it and wrestle it away from them, etc., and that somewhat applies to a sword as well (if you’re wearing gloves, or just willing to sacrifice a hand).

An arrow is only effective in the exact direction of the arrow. Being bonked with a spear will appropriately reduce your combat effectiveness, not to mention side cuts, and it’s a lot harder to catch (and hold) one than to make contact. You can dodge an initial stab, sure, but then you’re still facing someone with a pointy thing at the end of a stick that puts you at a close range disadvantage. It’s a lot of chances to take compared to arrows. The question isn’t what’s perfect, but what’s better and a close range weapon at close range is clearly better.

Also, I can slam the non-pointy end of the spear into your foot, or your groin – at close range, a spear can be used as a fighting staff, with a bonus pointy end.

Though this depends somewhat on the length of the spear.

“If someone wants to take a chance they just wait for a moment when you are not paying enough attention and jump out of the way of the gun and start throwing punches”

That means that “holding at crossbow/gun point” can still work if you have multiple people training their weapons on one, right? E.g. if you have multiple police officers and one criminal.

I think the real reason is that crossbows can only shoot once, so miss and you’re dead. Even a regular bow fires so slowly that at point blank range you don’t have the time to reload (although this would never come up in real life–as Bret pointed out, no one holds their bow in a drawn position for any length of time). With a spear, if the point “misses” (ie, they evade the point) you still have other options. A sword even more so. In fact, this is probably the best use case for a sword.

This is where another of Rules Of Gun Safety applies: be mindful of what’s behind your target. If you have to turn and shoot, and someone else also has to turn and shoot, there’s a good chance you’ll be in each other’s line of fire.

You only hold people at gunpoint from a sufficient distance as a last chance. Then there’s very little turning to do so dodging is just dodging into less accurate gunfire and more people just reduce chances of missing.

“A loaded gun pointed at someone has too high a likely hood of going off to risk pointing it at anyone you are not serious about killing. Either you are serious: pull the trigger, or you are not serious: so you shouldn’t have the gun drawn in the first place.”

Or, alternatively, you think that if you don’t have your gun drawn the person is going to do something that will lead to you shooting them, and so you draw out so they think twice before being stupid.

It should be noted that modern light crossbows are somewhat misleading. At the point where the question of “Holding someone at crowssbow-point” is relevant, you’re not talking about modern hunting crossbows, but rather either very heavy war-crossbows or the small self-defense crossbows like the pistol crossbow or the Chu Ge Nu. The former are as unwieldy as a rifle, the latter don’t actually have a lot of energy to impart, which means their ability to kill is practically non-existent.

Firstly, unlike a gun cartridge holding the bullet, the bolt sits pretty loose in the groove, and can be easily dislodged by jostling or holding the crossbow at an downwards angle.

But far more importantly I’d say is the noise. A firearm is *loud*. When it fires a shot, the noise alone disrupts your reactions, whether you’ve been hit or not.

Brilliant article, thanks! Two points to add:

1) The musket brought way more power to the battlefield, like you say, but it also gave that power to a soldier who didn’t need to be as strong or as skilled as an archer was. The low barrier to entry for the user was just as important as its increased power.

2) In the types of scene you mention, when we do see the (unrealistic) effects of the arrow volley, it never seems to have any meaningful effect on either the morale or the effectiveness of the party doing the charging. This just further reinforces the silliness of the trope IMO: if arrow volleys were as effective as shown, then it would be much harder to get a body of troops to charge at archers.

I agree with the other commenters who’ve pointed out that volley fire and firearms drill is as much about safety as about any tactical value. Firelocks are dangerous to the user, early ones especially so because you have actual burning matches around the place. They’re also complicated to use – 17th century drill manuals show something like 17 separate steps to loading and firing a firearm. Easy to get wrong under stressful situations. (As late as the 19th century you find muskets on battlefields which have been loaded multiple times but never fired, as well as people firing their ramrods by mistake).

So to get it right you break it down into lots of steps which are all done by everyone on command at the same time – if you forget what comes next, just listen for the word of command or look at what the guy next to you is doing. And to make it safe you ensure that you aren’t firing and sending sparks everywhere at the exact moment when the guy next to you is messing around with his black powder.

If you’re firing on troops advancing towards you, you’re only going to get one shot in effective range, maybe two, before they’re on you anyway, whether you’re volley firing or not. Because the reload time is so long and your effective range is so short, being Corporal Hawkeye who can reload in just 25 seconds vs being Private Mumblefingers who takes 45 seconds doesn’t make a difference – the enemy only spends 30 seconds in your engagement envelope anyway. So you aren’t losing anything by reducing your firing cycle to the speed of the slowest soldier. Whereas with a bow, it’s the difference between 3 rounds or 9.

Some other points.

Even in drilled armies of the 18th and 19th centuries, volleys were nkt or at the nest very hard to maintain after the first.

Also there were attempts such as platoon firing to maintain weight and sustain mental of fire… here correctly applied as they are using, fire arms.

Speed and weight of shooting with a “war” bow is as much to do with ammunition supplies. Looking at surviving commissions, before campaigns arrows are ordered rough at 2 or 2.5 sheaves ( a sheaf being 24 arrows) per bow.

Even allowing for archers brining their own arrows it wouldn’t take long to expend their supply, there are accounts of this happening but…

6 arrows a minute would mean 1 sheaf used up in 1 attack. Allowing for the engagement distance of 220yds

While this is for English HYW armies, the equation still holds.

Shots per minute.

Minutes when you can shoot your opponent

How many arrows do we have available.

A similar equation can be made with powder and shot armies, where even with a slower operational cycle the amour of ammunition carried and applied was markedly less than one would expect if troops were shooting as fast as they could.

The actual effect of missles.

When tested, whether bows or firearms, accuracy effects indicate results that aren’t reflected in accounts of battles through to modern times.

The greatest effect of missles is psychological. The potential of physical harm is manifested in psychological effects. However modern tests can’t reflect that so we continue to see see pentration tests, even though the first properly conducted 50 years ago when my father shot arrows at various armours and metal sheets at MoD facility

Logic as well tells us thag both armour and bows within a cultural package worked while evolving in an ongoing race to defeat each other.

As comparison, during ww2 tank crews were more likely to abandon a tank than die in it. While this may have been to do with the tanks mobility or its weapons being knocked out, it also happend that they just abandoned be cause they were taken under fire. This also doesnt include tanks withdrawing. Or things like Tiger fear. Where the idea of the danger of the danger of enemy weapons, not always true, altered troops and crews behaviour.

At the end of the day there are complex factors involved and many are not easy or possible to quantify.

Not everything that counts can be counts. And not every thing that can be counted, counts.

“during ww2 tank crews were more likely to abandon a tank than die in it.”

Planes were cheaper than pilots during the Blitz. I wonder if tanks were cheaper than crews during the later campaigns.

That was really only true for the West of course. Possibly looking at German and Russian statistics might show a different picture. Though whether you can trust them is as consideration.

As i recall I was similar across the board.

The economic cost of the kit has nothing to do with the person or crew abandoning it. That’s a strategic consideration, like ransoming high status combat personal. It’s a djnacial gain, a material gain, you keep their kit, and a longer term insurance to be kept alive as and when you get captured.

The point in regards this topic is that the actual lethality of the situation is less important than people’s reaction to their perception of it. Whether that’s medieval armour or battle tanks.

The effect of medical archery is in how it affected people’s mindset and willingness to keep closing and the physical bunching and compression it caused, rather than how well it could penenetrate the armour it was shootjng arrows against.

Though of course relatively few of the total would be wearing the best armour for the time, so the effects of all types will be greater on them and the seckdnrg effects, trying to move forwards, while being pushed from behind over fallen bodies, however they end up on the ground.

My understanding (I don’t have a cite, unfortunately) is that German WW2 doctrine called for crews to remain in disabled tanks and continue firing. Of course, the tank was a sitting duck at that point, so the doctrine wasn’t always complied with.

Doctrine like the cost of kit is besides the point, especially if, as you say, they also didn’t follow it. It’s one thing to stay with a mobile tank.thats lost a track, it’s another to stay in one that is being his by the enemy.

Knowing your armour or tank etc is 90% proof say, but the more you are being hit, the more likely you will be hit by 1 of the 10%, and that will have a psychological effect, especially if you can’t do anything to strike back, whether out ranged, operating at less effect or not able to reach the enemy lines for another 100 or more yards… all while getting hit

I think this is a situation where a focus on formed archers and heavy infantry is pretty unrewarding; the notable thing historically is that archery formations aren’t often a thing in places where heavy infantry is highest concern — as Mr. Devereaux points out the lethality is simply not there, and if you can get such an organized force together then the obvious thing is to mobilize them as the much more effective heavy infantry your mode of warfare centres on.

In a heavy infantry dominated context whatever fighters you don’t have the resources to mobilize as heavy infantry go into easier loose skirmishing roles. It’s when cavalry enters the mix that archery starts to be a formation activity; obviously imperative when facing horse archery, still also the best option when facing shock charges since, as the post points out, horsemen are innately more vulnerable to missile fire in a number of ways.

I’d append another, subtler consideration: closing in at a high pace might get past archery faster, but equally the higher relative velocity means that arrows which do hit are more lethal than they would be when directed at a slow or stationary target. And for that matter the impact of archery can be compressed temporally to a degree by firing very powerful shots rapidly, even if this would be unsustainable over a longer time period than the cavalry’s charge.

Excellent, as always.

I’ve been wondering if/when you will take a look at the Wheel of Time series. Season 1 is a weird mess but things improve, and season 3 is great fun.

There is a battle towards the end of Season 3, where basic fortifications, channeling, archery, basic formations and morale all feature. I think you would like it, it is more “realistic” and less “Hollywood” than alot of stuff.

If I may infer something, I think the one reason why filmmakers keep using the arrow volley is because coordinated actions implies professionalism and competence on part of the shooting army while individual actions are signs of disorder and lack of preparation, so directors who are not aware -or don’t want to be aware- of the dynamics of the pre-gunpowder (and early modern) battlefield stumble upon this mistake.

I could see a “pseudo-volley” at the start, but not as a deliberate tactic to mass fire.

Instead, it would simply be from everyone starting out at the same point that’s close to sending an arrow downrange. If you’ve deployed but aren’t actually fighting yet, (e.g. because the brass are trying to talk the enemy into simply surrendering the field), you’re probably going to be standing in a way where you can fire as quickly as possible but aren’t going to get tired. Thus, when the fighting does start, there isn’t going to be a lot of variation in when everyone sends their first arrow.

Of course, by arrow three or four things will have spread out into the constant rain of arrows.

Six ranks for a formation of musketeers is actually on the thinner side of formation depth. The Dutch army, which is traditionally considered to have introduced firing by countermarch into European warfare, deployed their infantry into nine or ten ranks. Six ranks as standard only become common with the in the Thirty Years War, first with the Swedes and afterwards spreading to their allies who were using the Dutch standard. Their enemies used similar or slightly deeper formations of 16, 12, 10 and eventually 7 ranks.

But did archers shoot in ranks in that archers behind the front rank could still shoot? Because I cannot imagine that they all lined up in a single extremely long rank when you have thousands of them.

Burgundian Ordonnances from the late 15th century mention archers standing in one rank behind kneeling pikemen and shooting over the pikemen’s heads. It might theoretically be plausible to do this with two ranks of archers, though it’s probably more likely that archers fighting in close order simply didn’t stand in formal ranks and instead filtered through back and forth individually as the ones in front tired out and the ones in the rear replaced them.

When you’re shooting at the limit for your bow, you angle the shot up at about 42 degrees for maximum range (you aren’t actually aiming at anyone, you’re laying down a rain of arrows not unlike WWII carpet bombing). So the second row are shooting over the heads of the front row, etc.

I confess that I skipped over much of the article, and most of the comments, so I may have missed discussion of the chemical warfare aspect.

It is, I believe, an accepted fact that the Henry V’s archers at Agincourt were naked below the waist, because dysentery was rife in the army. Dipping your arrow head into the resulting mess on the ground meant that even a cut from one would cause sepsis; although it didn’t immediately incapacitate a soldier it meant that by the time of the next battle he would be ill, or dead, and reduce the available soldiers for your enemy.

I’ve heard various theories of chemical warfare connected to archery.

I’ve seen no evidence for it. Other than tbe fact that a pentrating would on a battlefield is bound to bring infectious material into the wound.

On a basic logic level the concern in battle is now, stopping the enemy at some possible time in the future when they may or may not get an infection makes no sense. Add in factors such as wanting ransoms etc. Again makes these ideas anachronisms at best.

So, to summarize: bows do poise damage?

“Note that there is a much better much of the battle” – much better map? Depiction?

It turns out we do have a source for European crossbows using countermarch volleys.

Leonardo da Vinci invented it.