This is the fourth part (I, II, III, IV, V) of our series asking the question “Who were the Romans?” and contrasting the answer we get from the historical evidence with the pop-cultural image of the Romans as a culturally and ethnically homogeneous society typically represented with homogeneously white British actors speaking the ‘Queen’s Latin’ with a pronounced insular accent.

Last week, we extended our time frame from the Republic to the Empire, looking at the ways in which first Italian and then provincial elites were brought into the Roman elite (both literary and political). We saw that while these elites forcefully adopted a Roman identity, they also kept hold of their own original identities, layering the identities on top of each other and thus being both Roman and provincial or both Roman and Italian. Pointedly, we focused on the period up to around 180 AD, the long stretch of Rome’s maximum power, wealth and territorial extent, showing that trying to connect the increasing diversity of the imperial elite to ‘decline’ makes a catastrophic, century-sized error in chronology.

This week we’re going to shift our focus away from the senatorial elite in Rome (though we will still in many cases be dealing with elites because that is whose likely to have had their appearance recorded) and move out of the city of Rome, in order to answer the question that I have already been accused of ‘dodging:’ ‘what color were the Romans?’ As we’ll see in just a moment, that question is founded on some flawed assumptions, but exploring the very literal meaning of that question can serve as another way of charting kinds of diversity within the Roman world. Were there certain ways for a person to ‘look’ Roman? We have already addressed religious, linguistic and cultural variety within the Roman world and indeed within the Roman citizen body, but if one looked down the street of a Roman town are we likely to see a relatively homogeneous group of people – similar hair, skin and eye color, height, etc. – or a wide range?

What color were the Romans? As we’re going to see, the answer is most of them.

But first, as always, if you like what you are reading here, please share it; if you really like it, you can support me on Patreon. And if you want updates whenever a new post appears, you can click below for email updates or follow me on twitter (@BretDevereaux) for updates as to new posts as well as my occasional ancient history, foreign policy or military history musings.

(Note: This is going to be an image-heavy post, particularly with a lot of Roman artwork. Some of that artwork, as ancient artwork is want, shows men and women in varying states of undress. I have not used any artwork that shows explicit sex acts (though I do note the existence of such), but there is some nudity.)

Rome in Color

Now, as I go through all of this discussion on ethnicity in the Roman world, I know there is someone – perhaps many someones – insisting that all of these different groups in Italy at least aren’t really different because they are ‘white’ or alternately insisting that what I am doing is dodging the question of skin color (by, one assumes, cowardly hiding behind the evidence that it mattered less to the Romans than other distinctions). First off, I want to note that I think this argument begins from a mistaken premise: it is assuming that the divisions we impose today on our culture are fundamentally true in all times and cultures and so we can impose them on people in the past who may have viewed other categories as more meaningful. This is an error, as it ought to surprise no one that social construction is socially constructed (shocking, I know) and so the organization of a society (including questions of ‘who belongs’ and social hierarchy) depends on human perception about what is and is not important. Consequently, there is no one system of social hierarchy because each society will view the matter differently. Frankly, in many cases, the view that our categories can be cleanly retrojected into the past clearly comes from the assumption of Big, Important biological differences that would somehow make groups today considered ‘white’ more compatible even in the deep past when they themselves defined their groups very differently (or, to put it another way, the emphasis on ‘were the Romans white?’ accepts unscientific, garbage-nonsense racial categories as fundamentally true in a way that they simply aren’t; the easy Roman integration of North Africa compared to the difficulties of Roman Britain and Germany ought to be fatal to this view in any event).

This is not to say that the ancients were unaware that people came in different colors. One striking example is Asclepiades of Samos’ poem (c. 270 BC or so) praising the beauty of a black woman named Didyme:

Didyme has captured me with her eyes,

Alas! And I melt like wax before a flame

When I behold her beauty.

And if she’s black, so what?

Coals are too, and yet when we heat them

They glow like rose petals

(Trans. Larry Bean from Sententiae Antiquae, which also features the original text and a discussion)

It is worth taking a brief aside that even in the early third century BC, εἰ δὲ μέλαινα (‘and if she’s black…’) was a line that could be put in a poem without a whole lot of other context. The reader is assumed to have no problem creating a mental image of a woman both κάλη (‘beautiful’) and μέλαινα (‘black’), a good reminder that Africans (including those with darker skin) were not new to the Mediterranean but rather a regular sight in the towns and markets of the ancient Mediterranean. After all, the Mediterranean borders Africa on one side and was in essence not a barrier but a great highway knitting together far distant communities in networks of trade, discourse and warfare.

Likewise, even a brief reading of the ethnographically oriented authors in the Greek and Roman literary traditions shows an awareness of different skin colors, though it also shows that such authors were far more interested in customs and religion than skin color (this isn’t the place to lay out all of the examples, but Race and Ethnicity in the Classical World: An Anthology of Primary Sources in Translation, eds. R.F. Kennedy, C. S. Roy and M.L. Goldman (2013) has a fairly wide and representative sample; you will find quite a lot of descriptions – some more than a little fanciful or absurd – of clothing, marriage rituals and burial practices, but only very rarely a comment on the color of the people). They also considered significant chunks of Africa and Asia, at least as far as India to be as much part of their ‘inhabited world’ as Europe (ironically it was Britain – again – which, being on the wrong side of Okeanos, was conceptually the furthest away in at least some Greek and Roman geographic conceptions).

And therein lies a key point. As we’ve already seen, the Romans found other cultural signifiers – language, citizenship, social organization – more important than skin-color in understanding ‘who someone was.’ Ethnicity – the ‘stock’ or people one’s ancestors came from – might matter (both positively and negatively), but skin-color was at most ancillary to that (recall that in all of the Roman bigotry from last week, we saw several references to clothing, accusations of greed, deceptiveness, debauchery, attacks on religious customs, but only one passing reference to color). Again, this should not be mistaken for modern tolerance! The Romans could be – as we’ve seen – very bigoted towards other peoples and cultures, but people were far more likely to be described through religion, language, culture or clothing – the Romans were, after all the ‘people of the toga’ (gens togata, e.g. Vergil, Aeneid 1.282, Martial 14.124) – than by the color of their skin. Indeed, clothing in particular was a potent marker of Romanness and readers from last week may recall that it was the trousers – not the skin – of the Gauls to which the Romans objected when Caesar introduced some into the Senate (Suet. Caes. 76.2, 80.2). Such ‘uniforms of citizenship’ matter a great deal, as we’ll see in a moment.

Consequently, I have to note that as a historian, we ought to take ethnic classifications from the time and place when considering ethnic groups, rather than striving to impose our equally arbitrary classifications. And so that is what I have endeavored to do so far, focusing on the ethnic, linguistic and religious distinctions that mattered to the Romans in the three previous posts in this series. But we all know there is a certain sort of reader who won’t accept any of this if we don’t discuss skin color. So we are going to discuss skin color, though I should note this isn’t quite the same thing as discussing race. The question “were the Romans white?” is one of those ‘not even wrong’ questions because white/non-white was simply not a distinction that very much mattered to the Romans, who, after all tended to view many supposedly ‘white’ people as more distant or foreign to them (e.g. Gauls, Britons, Germans) than many people who would be regarded today as ‘non-white’ (North Africans being the most obvious example). The thing is, while skin-tone is a real physical, biological thing, racial categories are ‘socially constructed’ (read: made up by people and not fundamentally rooted in the natural world) and different cultures and different times define them differently. Famously, some groups seen as obviously, clearly ‘white’ today were excluded from narrower definitions even relatively recently in the United States. And so the question ‘what race were the Romans’ is fundamentally flawed because it relies on importing a set of racial categories that the Romans didn’t use.

But because this is a question people have, we’re going to answer it and so discuss skin color in the Roman Empire, with a particular focus on Roman citizens because, as we’ve discussed, that legal status tended to be by far the most important signifier of if one was a Roman or not. Though ironically, as we’re going to see, we’re going to use all sorts of means to tease out Roman citizens, from the towns they live (which have citizen status) to the clothing they wear, to the social strata they are in, to whether or not they happen to be emperor, all of which will serve infinitely better in telling us who is a Roman and who isn’t than skin color.

Pictures in Pompeii

So, all of that preamble out of the way, we get to the question at hand: what color were the Romans?

Most of them. They were most of them. Indeed, surprisingly close to all of them.

This is actually one of those questions where we need not guess. We can get a sense of this by looking, for instance, at Roman frescos, quite a few of which survive. Fresco (technically buon fresco, the form of fresco the Romans paint) is a style of wall painting where the pigment is applied on still-wet plaster, so that the pigment mixes with the water in the plaster and when that water dries the pigment isn’t merely on the plaster but in the plaster. Consequently frescos which end up buried can have their colors very well preserved and (as we’ll see) fresco painters can recreate a wide range of skin-tones very accurately. Consequently, and I want to stress this, the ‘what color were the Romans’ isn’t a question where we need to guess; we know They very literally painted us a picture.

Naturally, the range of skin-tones we might see in fresco is going to vary by place so I wanted to start us off as near to Rome as we could get while still having a good broad sample range to work with. That means we’re going to focus on artwork from Pompeii, a town in Campania, south of Rome, which had a whole chunk of Sulla’s veterans (Roman citizens all) settled on it in the 80s. Consequently, in terms of population make-up, Pompeii actually makes a pretty solid stand-in for Italy writ large and we can be sure that essentially all of the free persons in Pompeii – certainly the sort wealthy enough to be commissioning large frescos – are Roman citizens, so this is all at least art for citizens. Pompeii also gives us a really strong terminus ante quem (the last possible date a thing can be) because Mount Vesuvius utterly annihilated the town and buried it under literal tons of ash and soot in 79 AD. That’s also handy for what we’re doing: there can be no accusation that these images reflect only the later more thoroughly blended Roman Empire because all of them were produced no later than the first century (many are older). All of that actually makes Pompeii a fairly effective stand-in for Roman Italy’s skin-tone range as distinct from the (wider) range of the entire empire, which is in turn valuable because Pompeii’s evidence base is so robust as a result of the circumstances of the city’s aforementioned destruction-by-Vulcan. So to repeat, for this section all of these images are from Roman Italy, no later than 79 AD.

All of that said, Picture Time With Dr. Devereaux!

As an aside, note in the banquet scene, viewable more closely here, how class and color interact: some of the enslaved servants here (esp. bottom center) are notably lighter skinned than the aristocratic family, while another (top, second from right) is darker skinned. To the Romans, fair-skinned Gauls and dark-skinned Africans were equally foreign.

One thing you may immediately note is that the women in these scenes are consistently lighter skinned than the men. That’s not an accident; fair skin in women particularly was part of the Roman beauty ideal (as it had been for the Greeks). Elite, upper-class women weren’t supposed to be tan from being out in the sun and they also used white makeups to make them appear paler (including white lead, what would later be called Venetuain ceruse, which was about as healthy as the phrase ‘powdered lead-based cosmetic’ makes you think it is). Of course this does not mean that all of the fair skin color up there is nonsense; it is clear there were very fair-skinned Romans (there are some fair-skinned men in there too!), but that there were also very tan and olive skinned Romans (and as we’ll see in a moment, also black and brown Romans). But the impact of beauty standards here means that I suspect we ought to take the male skin-tones from fresco as a closer indicator of the natural skin color of people in first century Roman Italy. Chances are there were just as many tan and olive skinned Roman women but that, because of those beauty standards, they tended not to be depicted that way in artwork (or tended to be of the sort of social class that didn’t get depicted in artwork).

I have tried here to be representative of the sampling though I have also tried to keep the images mostly family friendly. There is also a large corpus of very sexually explicit fresco from Pompeii which I would note, if anything, shift the balance of skin-tones, particularly male skin tones (for the reasons just discussed), somewhat darker than the sample here (a lot more men with fairly deep olive skin, though women remain very fair skinned). But we can see pretty much the full Mediterranean skin-color range here, from very fair skin (especially among women) to fairly deep browns. Going by the Fitzpatrick scale, a standard six-grade classification of human skin color, we look to have at least one clear example of nearly every point on the range of light-to-dark human skin tone. In fact, let’s take the actual Fitzpatrick scale (diagram via Wikipedia) and contrast it with ‘swatches’ of skin-color from these frescos so we can see that.

And I want to be clear here, if anything, Pompeii should be a relatively more homogeneous, insular sort of town. It isn’t the vast world-port of Rome or Carthage and because of Sulla’s veteran settlement its population would have consisted substantially of individuals whose families had Roman citizenship before the Social War. Moreover, because Pompeii stops existing courtesy of the local volcano quite suddenly in 79 AD, we know we’re not viewing the more blended Roman world of the high and late empires, but rather a decidedly Italian-Roman milieu.

And yet, even before we go into the provinces (which we will in just a moment), the skin-tone range in Roman Italy is already very wide, even in the two first centuries. And that should be no surprise, this is a Mediterranean culture which has been in trade and cultural contact with the rest of the Mediterranean, including Egypt and North Africa for centuries. It should also, of course, be no surprise to anyone who has been to Italy (or really anywhere on the Mediterranean littoral) and seen the relatively wide range of human pigmentation there now. The color range difference between Mediterranean Europe and Mediterranean Africa has never been particularly vast because these communities have been in contact with each other since at least the beginning of the iron age, if not earlier. The Mediterranean is not a wall; it is a highway and has been since antiquity. Instead the idea that there was some firm separation, that Italians were clearly ‘white’ in a way that, say, North Africans clearly wouldn’t have been is an assumption based on the Atlantic world of the early modern period, not the Mediterranean world of antiquity.

The problem with trying to import those modern categories is that the categories themselves – ‘white’ and ‘non-white’ – are artificial and only make sense in the context of the social structures that created them. In the Roman milieu the nonsense of that rigid categorization (and the great weight placed upon it) is revealed quite clearly by (as we’re going to see) fairly significant zones of overlap in terms of skin coloration. And that is before we even get outside of Italy…

Faces from the Faiyum (and elsewhere)

Unsurprisingly, the wide range of appearances we get for Roman citizens increases if we look more broadly at citizens in the empire outside of Italy. As in Italy, preservation makes the effort difficult. The artwork most frequently preserved are sculptures. But while we know that Roman sculptures were painted, often in very bold colors, that paint often doesn’t survive and can’t necessarily be confidently reconstructed. Paintings on perishable materials hardly ever survive (recall that we have a volcano to thank for the finely preserved frescos above). One exception to this preservation problem is Egypt: the hard dry climate enables the survival of all sorts of things that simply wouldn’t survive anywhere else. One such category of artwork are mummy portraits.

Mummy portraits were an Egyptian custom where a portrait of the deceased person being buried was painted on a rectangular board or panel, typically made of wood and placed in the tomb with the body. The practice itself represents an interesting cultural fusion on its own: a blending of Greek and Roman artwork styles with Egyptian burial practices. Beginning in the late first century BC the painting of these portraits runs into the third century AD (a handy date range for our purposes as it begins at the same time as Roman rule). The figures shown are mostly local elites – commissioning an artist for this kind of thing required at least some money, after all – though the wide variation in quality suggests that at least a fairly broad range of the elite engaged in this practice, not merely the very richest individuals. Let’s take one of these portraits and look at a few of the elements of it:

We have what looks to be a man, perhaps in middle age. A few things are notable. First, he wears a white toga (the standard formal Roman folded cloth garment, draped from the left shoulder) and a white tunic with a purple stripe (two, in fact, the other is concealed beneath the toga). When I show my students this picture, I joke that the man might as well have worn his, “I AM A ROMAN CITIZEN” t-shirt; the impact of the clothing here is similarly blunt. While a fellow might wear a toga in a variety of colors for fashion’s sake, this solid-white toga is the toga virilis: the distinctive formal dress of a Roman citizen. Meanwhile, that purple stripe on his tunic is the angustus clavus (or angusticlavius, literally ‘the narrow stripe’). That too was a bit of clothing reserved as a marker of status – whereas the toga virilis says “I am a Roman citizen” the angusticlavius says “I am of the equestrian order” (nothing to do directly with horses by this point, it merely indicates wealth and that the individual isn’t involved in politics in Rome). In short then, this man – or more correctly, his surviving family who commissioned the portrait – is telling us, in no uncertain terms, “I was a wealthy Roman citizen.” I want to stress that point: there was no real distinctive national appearance that indicated a Roman – no particularly Roman hair color or what have you – but there was a distinctive dress that indicated citizenship, which only citizens were entitled to wear and which was so important the Romans went so far as to call themselves the gens togata (‘the people of the toga’).

But of course we can see other things about him. His hair-style isn’t really typical of fashion in Roman Italy. And of course he has that star-diadem, under which he’s arranged three locks of his hair; that is meant to tell the viewer something too. In this case, it is meant to tell us that this man is associated with the cult of Serapis, probably a priest. Serapis emerged as a distinctively Graeco-Egyptian fusion deity in Egypt in the third century, promoted by the Ptolemaic dynasty in an effort forge some common ground in their kingdom between Greek and Egyptian subjects. Serapis was worshiped as an aspect of Osiris (merged with the bull Apis). This is, to put it mildly, not a Roman god (though the worship of Serapis spread through the Roman Empire from Egypt, though it doesn’t seem to have lost its Egyptian connotations). So our fellow is also telling us, just as clearly, “I was an important practitioner of an Egyptian religion” – keeping in mind that this fellow lived in Egypt. This is a good example of identities layering rather than obliterating each other – visually the artist and the deceased’s family have chosen to convey both that this man was Roman and that he was Egyptian (or at least Graeco-Egyptian).

But of course that fact about clothing is really very handy for us if we want images from the provinces in color where we can know with a high degree of certainty that the subjects are Roman citizens, since anyone wearing either the toga virilis or a tunic with that clavus is declaring their citizenship (in a way that would get them in rather a lot of trouble if they were lying!). And it turns out there are around 900 of these mummy portraits from all over Egypt. So what do our Romans in Egypt look like? Well…

Top Row (starting from the left): inv. EA74715, dated 100-120AD; EA 74718, dated 80-100AD; EA74704, dated 150-170 AD, all from Hawara in the Faiyum, Egypt.

Bottom Row (from the left): EA63396, early second century from Rubaiyat, Egypt, EA 63396, early second century from Rubaiyat Egypt and EA74707, 70-120 AD, from Hawara in the Faiyum, Egypt. All six are now in the British Museum.

If your mental image of ‘Romans’ for the Roman Empire doesn’t include these six fine gentlemen, update your priors! But it is also worth noting the variety we have here, even though all six of these portraits are from one province in the Roman Empire (Egypt). We have a range of skin-tones, from fairly light olive to deep browns and also a range of hair, from straight to curly to very tight curls. But all of these fellows have one thing in common which is that their dress marks them out as Romans – something they very much wanted you to know.

Now, mummy portraits weren’t only for men but assessing the status of women in these portraits is tricky. Women’s tunics could also sport clavi and in a wider range of colors, but these patterns didn’t have the same clear “I am a citizen” message as the man’s white tunic with purple clavi with toga virilis and so it can be hard to gauge citizenship status simply from a woman’s clothing. That said, the style was a Roman fashion not an Egyptian one (to my knowledge) so at the very least we may say (and indeed, others have said) that the women of many of the mummy portraits from the Roman period in Egypt are wearing Roman-style dress, although often with local touches. Some examples:

Top (from left): EA74706, 100-120; EA74712, 100-120; EA74716, 55-70

Bottom (from left): EA74713, 55-70; EA74710, 160-180; EA63395, 100-120. All are from Hawara in the Faiyum except for the last which is from Rubaiyat. All now in the British Museum.

Again, we can see here a wide range of skin colors, from the fashionably (for the Romans) fair-skinned (top center, bottom left) to darker (and probably truer to life in many cases) skin tones. These are upper-class ladies and so their portraits show a conscious effort to display wealth (like the expensive perfume bottle that the woman in the bottom right caries, or the heavy use of purple-dyed cloth) and also their fashion sense, which mirrors the fashions of the Italian Roman elite quite heavily. Again, we can’t know these women’s status from looking at their clothing (besides that they are clearly fairly wealthy elites) but the fact that clear displays of citizen status are so common among the men buried in the same condition – men of the same social milieu who may well be these women’s fathers, brothers, sons or husbands – strongly suggests that most of these are provincial citizen women. At the very least we may say for certain that they are all interacting quite a lot with the broader Roman world and its trends.

Moving out of Egypt our evidence thins greatly, but there are still some things we can say. We have evidence of citizen communities in Gaul from a very early point (you will remember Claudius talking about them last week) and it should take relatively little convincing to imagine that Roman citizens native to Gaul (=France) or Britain were likely on the fairer end of the skin color spectrum as what we see here, even if we don’t have a lot of surviving artwork from the region to tell us that. Of course that doesn’t mean that all of the residents of Rome’s northern provinces were fair-skinned locals either. A Roman woman, whose skeleton and grave goods were found buried in York, England (nicknamed the ‘Ivory Bangle Lady’ after her bracelets) appears to have been of North African extraction, though isotope analysis suggests she spent her childhood in Britain. There is some debate on the validity of the analysis that marks her as North African, but there’s no reason to be skeptical about Africans in Roman Britain; the Historia Augusta (SHA Sept. 22.4-5) notes one such – an Aethiops e numero militari at the end of the reign of Septimius Severus (r. 193-211). You’ll see that phrase translated as ‘an Ethopian soldier” but aethiops was equally a generic way in Latin to refer to someone as being black, regardless of where they came from. Now the Historia Augusta is often quite unreliable as a source, but the point here isn’t the truthfulness of the particular episode, but the fact that a black Roman soldier serving in Roman Britain was, to the author of the Historia Augusta, a perfectly reasonable thing to posit. And of course the same would be true of Roman soldiers from Gaul, Spain, Italy or Britain serving in Africa or the East. We’ll talk more about the Roman army’s role in all of this next week, but in brief it functioned to move individuals all around the empire as units were transferred from this or that frontier.

But back to our portraits: all of these people were Romans; that part of their identity was probably never seriously in doubt. Many of them had likely been Romans for generations. Indeed, we should observe the profundity of what these people and their families (since it was the families that would have commissioned the portrait as one generally cannot commission artists while dead), reaching through time to convey the essentials of themselves chose to show us. A great many of them, it seems, put a great deal of effort into communicating to the future that proudest of boasts, Romanus civis fui – ‘I was a Roman citizen.’

It must have been very important to them to say it.

The Color of Purple

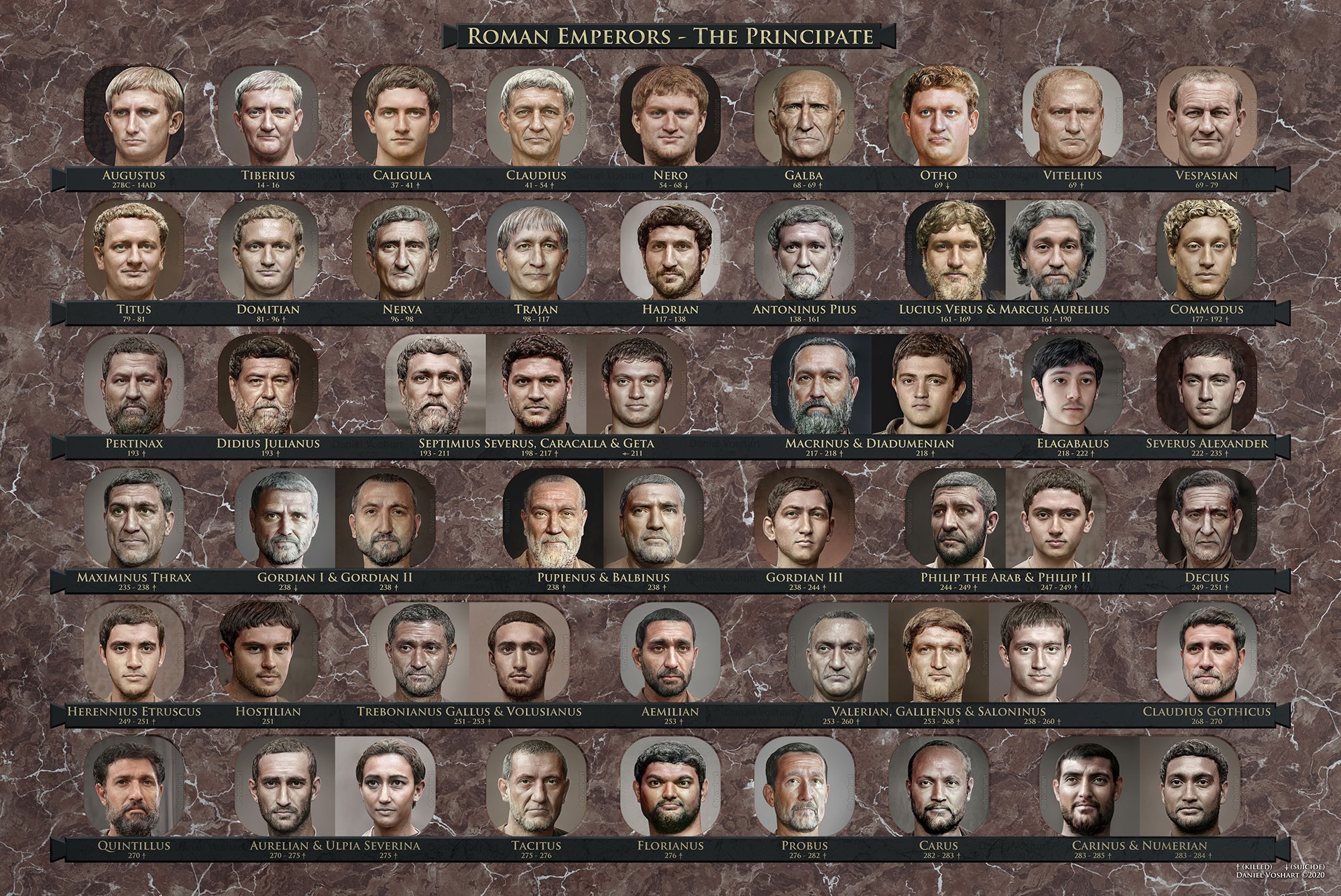

And yet this wide range of skin color is rarely captured by the popular imagination or absorbed by the public, often because it simply does not appear in the materials produced for them. We’ve beaten up a fair bit here on HBO’s Rome (lest anyone think I am bashing for bash’s sake, I will say I actually like HBO’s Rome quite a bit), but it is hardly alone. For another example take the recent project by Daniel Voshart to visual with modern software the faces of the Roman emperors. This project – which I will say, I think is quite good though we are about to point out some flaws – was feted everywhere and shot all around the internet:

And I do mean everywhere. Here it is at The Verge. And Smithsonian Magazine (mercifully using the 2.0 versions of the portraits). And Popular Mechanics. And also a 30 minute Youtube video by the World History Encyclopedia (which, by the by, is not a good or reliable website, despite its popularity with students; Wikipedia is honestly better. Pointing out some of the serious errors in their articles could be a blog of its own for there are many). And it was all over social media. Which is a real issue because the original set of portraits were so badly flawed they had to be reissued and even then I think there are serious problems in how the skin color of these emperors is reconstructed.

And I want to note at the outset that I am also not here to bury this chart nor its creator. This was not a fundamentally flawed project and I don’t mean to imply that it is, merely that the sort of errors it fell into (particularly in its 1.0 version) speak to the pervasiveness of the problem we have been talking about. Because this chart assumes unless otherwise indicated (and sometimes even when otherwise indicated) that Roman emperors were essentially white – and very white in most cases – as its baseline assumption. Now, to his credit, Daniel Voshart reissued the chart after getting some criticism of some of the portraits which darkened some of the skin colors used, though the treatment was applied only to specific emperors, not generally, whereas I might have suggested that systemic errors require systemic solutions. Moreover, and Voshart can hardly be faulted for this, the reissued chart made much less of a splash and spread over the internet quite a bit less than the original, making this an instance where Voshart is both innocent victim of the ‘whitening’ of Rome in the popular culture and an accidental purveyor of the same. To be clear, I am not faulting Voshart; it seems to me a rather difficult and big thing to admit the mistake and change the chart and I respect the honesty to do that openly. He seems to be doing his best and nothing is perfect on the first run. But I do want to interrogate the mistakes that led to the first problem chart, some of which remain in the re-issue:

I think we can see a trend in the thinking here with the very first portrait, of Augustus blown up a bit from the chart:

Now, what do we know about how Augustus looked? Well, we have a lot of sculpture, and Voshart has done an excellent job with his software in capturing the structure of the face we see in statues of Augustus. One thing I was made to learn as part of my MA was the ability to recognize the first 18 or so emperors on sight (a thing you can do if you know Roman imperial sculpture well enough) and, absolutely, that’s Augustus. But of course those sculptures are in marble and while they would have been painted originally, that paint is now gone, so how do we interpolate the color of Augustus’ skin or hair or eyes? Well, good news, Suetonius essentially tells us (Suet. Aug. 79; Voshart has this citation wrong in his notes due to an error in the English transcription on Perseus, for which he can hardly be faulted though I assume this error is indicative of Voshart’s lack of familiarity with the Latin which is about to matter) that Augustus hair was leviter inflexum et subflavum (lightly curly and dirty-blond) and his skin was colorem inter aquilum candidumque (“colored between dark and bright,” by which we should probably understand ‘tan’). But somehow dirty-blond and tan became, as above, very blond and quite fair; this particular portrait is almost entirely unchanged in the reissue (the hair is a little darker). That Augustus is colored pretty close to Simon Woods’ portrayal of Octavian in HBO’s Rome (below), except that Simon Woods is an English actor and Octavian was…you know…Italian? And apparently at least a little brown by Italian/Roman standards!

(Language note: this is a case where I think familiarity with Latin matters, because color words are always finicky. The Romans have a word for ‘blonde’ or ‘golden haired’ and it is flavum, so if hair is subflavum is isn’t blonde, it’s quasi-blonde, almost-blond but dirty-blond is, well, at least a fair bit brown; the reconstruction is really very blond. Meanwhile his skin is between aquilum (‘dark’) and candidum (‘white’) according to Suetonius. Candidus here is easy – that’s very white, like chalk or paper; here as a skin-tone, I think Fitzpatrick I or II. How dark is aquilum? That’s more difficult, aquilum is a rare word but here we have the grammarians to the rescue, particularly Sextus Pompeius Festus (1.1) who notes “Aquilius is a color tawny and almost-black” (aquilus color est fuscus et subniger; Latin niger for ‘black’ has exactly the English cognates you think it does); aquilum is probably around a V on the Fitzpatrick scale. So Augustus’ skin is somewhere in the middle between ‘very fair’ (candidum) and almost-black (aquilum). Probably that’s something like a III or IV on the Fitzpatrick scale, but here we’ve got, generously, a II, almost I. That’s simply not what Suetonius’ Latin says.)

The more obvious initial problem was with the version 1.0 of the Severans. That was easily what drew the most immediate criticism because we have surviving artwork in color of Septimius Severus, here juxtaposed with Voshart’s version 1.0 and version 2.0 depictions of him:

Center: via wikipedia the Severan Tondo (c. 199) showing Septimius Severus, his wife Julia Domna, and their sons Caracalla and Geta (Geta’s face is blotted out; after Caracalla assassinated his brother he had his images removed in a damnatio memoriae)

Right: Version 2.0 of Voshart’s reconstruction.

Again, good on Voshart for constructively responding to criticism, but also it isn’t hard to see the problems between the frankly pale original reconstruction and the red-brown contemporary portrait (which is, to be clear, not obscure; it is a famous piece of artwork and on Wikipedia). Even the reconstructed version doesn’t quite catch the hue of the artwork which I think implies something closer to a Fitzpatrick V than what we have, which is perhaps a III or maybe a IV. And that dark skin makes a lot of sense! Septimius Severus was born in Leptis Magna in what is today Libya; his father at least seems to have been of Punic extraction and so may have been living (and marrying) in North Africa for centuries; his mother was from an Italian family, but it isn’t clear how long they’d been settled in North Africa.

How does a glaring error like that get made for an emperor for whom we have a contemporary color-painting? I should note that I hardly think the two emperors I’ve focused on here are the only reconstructions which have problems. Just looking at where the skin color of Roman era Italian artwork clusters suggests to me that nearly all of the Italian-born emperors probably ought to be rather more tan. The problem here then is that the reconstructions systematically whitened the emperors (through, I suspect, an error in the software used which was probably ‘trained’ primarily on very fair skinned faces). How does that happen and more importantly how does it go so easily unnoticed both by the creator but also by so many of the early evangelists for the project? The answer, of course, is what we’ve been talking about all along: the Queen’s Latin – the built in assumption that the Romans, or at least elite Romans, were mostly ‘white’ and looked at lot (and sounded a lot) like not just Europeans, but north-western Europeans. It is why the notion of a Roman Emperor who was not only African, but also at least brown if not black strikes most people as absurd, but of course it’s true. It’s not Septimius Severus who was absurd, it is the Queen’s Latin and the vision of Rome it promotes.

(Also, while we’re here, to keep noting the Roman trend in artwork towards lightening the skin of women, Septimius’ wife, Julia Domna, pictured above was a native of Syria, probably of Arab extraction and so while I cannot be sure, we may suspect that she was not generally so pale. The choice of skin tone may either be the artist trying to be flattering or it may reflect Julia wearing fashionable skin-lightening cosmetics, well attested in ancient sources as something fairly common. Nevertheless, it turns out unrealistic beauty standards are not merely a product of modern mass culture.)

Septimius Severus was, by the by, hardly the only emperor to hail from outside of Italy, although we have to be careful because some emperors with ‘provincial’ origins may have come from Roman colonies in the provinces (and thus be perhaps only a generation or two removed from the Italian elite). Nevertheless, we know that Trajan was born in Spain (though perhaps descended from Italian colonists; how much intermarrying there would have been there is unclear) as was Hadrian. Didius Julianus, briefly emperor, was born in Cisalpine Gaul (by that time part of Italy); his heritage on his father’s side was Gallic, from the Insubri, while his mother was from Hadrumentum, an old Phoenician colony in North Africa (SHA, Didius 1.2); he was a senior senator before briefly being emperor. Septimius was African, as noted, so Geta and Caracalla, his children, were mixed African-and-Syrian in ancestry; Elagabalus, his nephew was of Syrian origin, same as Julia Domna, as was Severus Alexander. Maximinus Thrax was…well, a Romanized Thracian as his name suggests; we needn’t believe the predictable slander in our sources (chiefly the Historia Augusta and Herodian) that brand him as a ‘barbarian,’ but he clearly was from Thrace. The Gordiani (there are three of them) seem to have been perhaps Anatolian in origin, being granted citizenship perhaps by Mark Antony, though by the third century that origin may have felt quite distant. Philip the Arab was…well, a Romanized Arab; sometimes this stuff is easy. And so on and so forth; Diocletian was Dalmatian, Constantine was Illyrian through his father and perhaps Bithynian through his mother.

It should be no particular surprise that Roman emperors from outside of Italy begin first slowly – with Spain and North Africa represented first – and then accelerate, particularly after the Constitutio Antoniniana expanded citizenship to all free persons in the empire in 212. That’s precisely the same pattern as we saw with senators and literary elites, as the Roman upper-crust slowly expanded to encompass a wider range of Romans, both new and old. But that expansion is important for us because it goes right to the question of who was a Roman – by the 190s, not only could a Spaniard, an African, a Gaul be a Roman, they could be the Roman without being meaningfully treated as an outsider (of the above, only Elagalabus and Maximinus Thrax seem to have been seen as somehow un-Roman by many of their contemporaries, the former for his Syrian religious practices which seem to have offended Roman sensibilities and the latter – who came up through the army – because he never actually visited the city and deeply antagonized the Roman senate, a mistake which cost him his rule and his life).

Would a Roman, In Any Other Color…

All of which brings us back to the pop-cultural representation of the Romans. As we’ve seen, Romans, both in Italy and beyond it, covered a wide range of physical characteristics. We see fair-haired Romans and dark haired Romans; Romans with straight hair, curly hair and hair with tightly coiled curls; we see Romans with very light skin, very dark skin and every color in between. And this should be no surprise because Rome was – as we’ve seen – essentially poised on a crossroad of crossroads, at the center of the Great Mediterranean Highway.

Again, contrast that with the popular image of the Romans:

We can see here quite clearly a few problems. The first is of course that we see none of that range of coloration from all of this Roman artwork we’ve been looking at. These fellows aren’t merely fair skinned, they’re uniformly so, which gives the – by now we’ve seen, wholly incorrect – sense of Rome and its Senate as homogeneous institutions when they weren’t. But of course the broader issue is that the Senate here is presented not merely as homogeneous, but as homogeneously white. Now this is the Senate of the mid-first century BC, so at this point we ought to expect them to all be Italians, but even by this point that would suggest a wider range of appearance than this (as we saw above with our Pompeian frescos). I’ve seen no indication anywhere that the Roman elite was notably whiter than the common Roman (although that sure does seem to be the impression you’d get from a lot of pop-culture depictions of Rome).

And there, at least, we come to the real problem with the implication of the Queen’s Latin: visually and aurally it claims the Romans as ‘white.’ And sure, if you are Spanish or British or German or Italian or French and you want to claim Roman history as part of your heritage, go right ahead. I will stick to my guns and declare it is still wrong to say anyone in the Roman world was ‘white’ (or ‘non-white’) in the sense that term is used today, but if you want to say that Roman history is ‘yours’ because some of the Romans looked like you do, came from the part of the world you do (or your ancestors did), go right ahead. Were there Romans who looked ‘white’ in today’s terminology? Absolutely.

But the uniformity of the Queen’s Latin – and the fierce, reflexive outrage whenever it is challenged – works to deny other people, people who trace their roots to Tunisia or Algeria or Morocco or Egypt or Syria or Anatolia or a dozen other places the ability to say that Roman history is ‘theirs.’ The Queen’s Latin declares (falsely) with the power of the visual medium that Rome was a ‘white’ man’s empire, re-imagining Rome in the shape of the white European colonial empires of the early modern period (empires we may truly call white because they were empires in which power and full membership was marked out by the color of one’s skin and the continent of one’s ancestry in a way that was not true of Rome). Subtly but consistently, this way of depicting Rome tells those students located in the upper 4/6ths of that Fitzpatrick scale (which is, to be clear, most of the scale and most humans), “this isn’t for you.” But it is for them, if they want it. Rome is theirs, just as it is yours – just as it is mine, though there is an excellent chance that a student whose ancestors hailed from Algeria would have a far better claim to Rome as their history than I do! And I want them to come study it with me because we all – whether our ancestors lived in the Roman empire or not – our world is built atop the Roman’s world, in some places literally and in some cases figuratively (though it is often the figurative foundations that are the more profound). And if the ‘you’ who is reading this is that student who wants to claim the Romans, regardless of where you come from – come study Rome with me, in whatever capacity you wish.

The impression that Rome was merely a ‘white man’s empire’ isn’t true to the evidence and it is both a detriment to our understanding of the past (including our ability to understand societies that valued different things than us, and so our ability to understand that we might choose to value different things too) and it is a poison for the study of the ancient world in general and Rome in particular, because we cannot afford to turn away even one eager student. It is long since time we abandoned the Queen’s Latin’s portrayal of the Roman world in favor of an accurate portrayal of the Roman world, with the helpful but secondary benefit that such a portrayal cannot help but be more welcoming.

Were there black and brown Romans? Yes, absolutely, without question. Were there African Romans? Western-Asian (or ‘Middle Eastern,’ if you prefer) Romans? Yes, absolutely, without question – our evidence on this point is indisputable. The evidence that Rome was a diverse society, by essentially any measure, is so preposterously strong – consisting of the unanimous testimony of every sort of evidence we have, including the endless complaining of Roman bigots! – that it is hard to view the continued popular resistance to this notion (scholarly resistance to this notion, from actual specialists rather than non-specialists straying out of their expertise to try to score political points, is effectively non-existent because there isn’t much evidence to argue from) as anything but stubborn bigotry of its own sort. So let’s say it once more, loudly and with feeling, for the folks in the back:

Rome was diverse. It was ethnically diverse. It was religiously diverse. It was linguistically diverse. It was culturally diverse. And, yes, though this mattered much less to the Romans than it seems to matter to us, it was color-diverse. And Rome was diverse from the very beginning; its strength was built on its diversity. Moreover, Rome was not merely diverse in the cheap way that all empires are diverse; the Romans did not merely keep multi-colored slaves (although, it is necessary to be honest about the uglier elements of Rome, the Romans did keep many different diverse peoples in cruel bondage), rather a great part – perhaps the defining part – of Rome’s triumph was in successfully integrating those many diverse peoples into itself, in allowing them to become Roman (to again borrow a phrase from Greg Woolf) without demanding they lose their own local identities. This sort of diversity was the thing that set Rome apart from its competitors, predecessors and successors and fundamental to Rome’s ability to leave such a strong legacy after its empire began to (very slowly) crumble.

Next week (assuming I can keep up my writing schedule), we’ll finish up this series by asking if Roman diversity led to the fall of the empire, as some claim. Spoiler alert: it didn’t – but heightened Roman intolerance might have.

Typos:

A Roman woman, whose skeleton and grace goods were found buried in York,

“grave goods”, I assume.

You’ll see that phrase translated as ‘an Ethopian soldiers”

soldiers or soldiers?

It amuses me that your typo correction itself contains a typo.

At least I assume that one of the “soldiers” in “soldiers or soldiers?” was meant to be “soldier” without the last “s”.

It really can happen anywhere (in fact I almost spelled wrote “tyop” instead of “typo” when I wrote this comment).

Oops. Yeah, I am not one to point fingers on typos.

Muphry’s Law strikes again!

Fixed!

“not only could a Spaniard, an Africa, a Gaul” -> African?

Fixed!

If someone were to fake Roman citizenship, how would they get caught (not asking for a friend)? Also, did wearing the toga virilis decline after the Constitutio Antoniniana? I would guess that displaying the status became less important when everyone was a citizen.

Somebody faking Roman citizenship wouldn’t be on any citizenship rolls, have any documents to that effect, or have anybody willing to vouch for their status.

Although, it seems that quite a few people more or less entered Rome, and then some years later claimed Roman citizenship. This was apparently an ongoing sore-spot for a fair number of body politic. if you could speak Latin and you moved to Rome, well, it wasn’t too hard to blend in after awhile. However, during the early imperial period actual birth certificates came into use, which may have cut down on the issue legally. However, in the aftermath of multiple civil wars the whole issue may have been hopelessly muddled in the city. And in the Republican period, given how many people wound up in Rome, intermarrying and living side-by-side, that that the question of citizenship was a right mess to begin with.

In many of the provinces, who held Roman Citizenship would have been a semi-public knowledge, although it would generally be documented somewhere.

But the courthouse burned down after the last proscription! Honest! –says every Not Real Roman ever…

Pro Archia 8, for anyone curious.

Found a YouTube video that addresses how people were expected to prove their citizenship:

Good post, I really agree with your two key points, that a) color is mostly a silly lens for Classical studies but b) literally whitewashing the Romans is wrong, and might make people feel unnecessarily excluded from trying to understand them. And of course in this one sense of relative diversity they are a positive model for America.

On the specific question of the pre-Empire Roman elite though, quite a few of them are described as ‘fair’, aren’t they (e.g. Caesar in Seutonius being ‘colore candido’)? or having russet hair – which is quite rare in modern Italy. Is it possible that there was a broader range both ways in coloring than in modern Italy? I note that even for Augustus, that if an adult is subflavum (which is a useful word for a common European hair colour, incuding my own!) then as a child they would likely have been blond, which again is not super common in undyed hair in today’s central Italy.

Women are paler because they stay inside.

Indeed, in the Song of Songs, a woman is described (in some translations) as black because working in the sun.

Roman women were a bit less cloistered than Greek or Levantine women, though if they did go outside, they would have been veiled (upper class women at least), which may have helped in avoiding tans.

Even the lower-ranking women would try. Pallor is beautiful in a woman because women are palest when they are most fertile — and runaway sexual selection has produced a distinct paling effect.

When it also speaks of high social status, that gets doubled.

Noting the popularity of skin-lightening lotions in many portions of the world…

Women are also paler because they have more subcutaneous fat, and fat is paler than muscle. Since paleness is a biological marker of femaleness, it tends, like most sexual markers, to be fetishized and exaggerated by both evolution and culture.

In Song of Songs 1:5 the Hebrew word שחורה is literally just black (followed by נאוה, which means good-looking – there was no white beauty ideal in Biblical Hebrew). Then in 1:6 the word is שחרחרת, which is a reduplication of שחורה that means blackish and has the same -ish meaning with a bunch of adjectives.

And that’s the reasoning behind fancy dresses and suits, especially white suits. They show off you can’t work. You can’t work presumably because you have other people to do any kind of work for you. This went to the extreme with female blouses, which have buttons on the other side so that they’re easier to button/unbutton for a servant.

The one about blouses is mostly a myth: things buttoned on the female side are actually slightly *easier* to button on your own… if that’s the way you’ve always buttoned things.

Back buttoned blouses and dresses are somewhat harder to button on your own, but even here:

* somebody with average mobility has a decent chance of being able to deal with the back buttons of a blouse, possibly also those of some dresses (it depends on the dress);

* people and especially women in the past rarely lived on their own, and even people who didn’t have servants could ask for help to a mother, sister, daughter or well trained husband to do that pesky button right in the middle of the back.

As for other clothing that is supposed to prevent people from working, for many of those there are period sources that point to it being used by the working classes, e.g. https://imageleicestershire.org.uk/view-item?i=7559 or https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Maid_and_mistress_in_crinoline._Punch_Almanack_for_1862-2.png

Of course, fancy dresses would use expensive materials that would be impossible for a working class person to afford (at least new), but that’s unrelated to their practicality.

The Fitzpatrick scale looks strange to me. I’m pretty sure I’ve met people darker than #VI, but not as pale as #I, even though I’m white with a blond mother. Also, the middle colors are literally yellow.

I think I’m as pale as I. I’m a blue blood in the original sense, my skin is so lacking in melanin that the blue veins are clearly visible. I take after the northern European side of the family. My brother on the other hand is II or IV, as he takes after the Sephardic/ Mulatto side of the family.

IIRC, it was only designed (by an american dermatologist) as a way of prediciting how people react to UV, but it has become widely used as a general classification of skin colour.

Look at Conan O’Brien–“I was born in a bog and was never intended to see the sun”.

Which is one of the things, my impression is often that british and some french people tend towards the paler than eg. scandinavians. (if you go to a beach in one of the popular touristy hotspots you’ll see tanned swedes and norwegains and burned-red brits and french)

That might just as well be because Scandianvians take sunscreen very seriously.

Sunscreen protects against tans too.

Also some people just don’t tan.

The ancient description of somebody being ‘black’ may well be entirely different from the modern usage which means persons of sub-Saharan descent, many of whom are very light skinned due to European admixtures. In ancient usage, as Mary points out, it may simply mean sun tanned or black haired. But the artwork certainly shows people we would call ‘Black’ today among the elites.

The convention of tinting men dark and women light in artwork goes back to the Cretans and Egyptians. Dark skin was a sign of virility just as pallor was feminine. I wonder if men were occasionally depicted as darker than nature just as women were lightened?

Fair skinned blonds certainly existed in the ancient Mediterranean world and such coloring was admired, but then as now olive to brown skin and dark hair and eyes was more common.

As Bret says skin tone was irrelevant to the Romans. Discussion of the color of Romans indicates our modern obsession with the issue.

I think older Japanese art also has pale women, darker/redder men. Might be as simple as who goes outside more.

one (ok three) words: lead white cosmetics…

People will not use paint to achieve a look that is not already preferred. A reason for the preference is needed.

You mention slavery…but I wonder if the ubiquity of enslaved people in Roman society – of all hues but many of them quite pale war prisoners from Germany, Dacia, Britain (and so on and so on…) – didn’t go a long way to reducing Roman skin-color bigotry?

If your mental picture of “low-status person” is “pale blonde German slave”? Your mental calibration of status might well never be based on color…

I’m not saying this happened, but I could imagine Romans associating any non-Italian skin color with low status.

The point is there was no Roman skin color. Romans didn’t label people by tint like so many of us do. And while pallor was admired in women it was emfeminate in men.

Non-Italian skin colors? Currently ‘native’ Italian skin colors vary wildly from north to south, from pale skinned people (albeit in a sunny country) to dark skinned ones (not ebony black, albeit some south italians are very dark skinned).

This isn’t that non-Italian skin colors don’t exist but that they are mostly very far from Italy: very pale skin from way upper north, very black from way upper south, not considering skin colors from East Asia. I could better imagine Romans associating non-Italian skin colors with exoticism.

Do we have any surviving account of ethiopians or chinese (for example) merchants or dignitaries arriving at Rome or another big Roman city and the reaction of the Roman population to their skin colors?

Current native Italian skin colour vary widely even in the same area of Italy (and even among people with surnames that aren’t indicative of recent internal migration – I know it doesn’t mean that there wasn’t an ancestor or ten from a different part of the country), excluding just ebony black and very pale (I and VI on the scale).

To the point where skin colour isn’t really the predictor of discrimination (of which in Italy there is still a lot), because the people who are getting discriminated are mostly impossible to distinguish visually from the one doing the discrimination. The most frequent discriminated people who are frequently met in Italy and *can* be distinguished to some extent (but not always) would be people from east Europe, and those tend to be somewhat paler than the ones doing the discrimination. I believe that *the* indicator of discrimination is language use, although of course dress and other cultural hints are also used.

Looking at the visual evidence from the past points to the idea that the variation in skin colour in Roman Italy was pretty similar to what we have today (other than the fact that today there are more tanned and sunbathing women 😀 ), which makes the geographical area inhabited by similar-enough people pretty wide, easily extending e.g. into India.

Sorry but Algerians are not black and most of them would have not been what in the modern world you call black in roman times the racist claim that North Africans are black is mostly made by African Americans to attack us and call us fake don’t spread misconceptions

I do not think he claimed Algerians are (what we would consider) Black, just that they tend to be darker than the cast of HBO’s Rome or Voshart’s portraits

Unless I missed something, I don’t think Algerians were ever said to all be black in this article, just that people we would call black today lived in the Roman Empire, and that Algerians are able to claim Roman heritage.

Gibbon calls five of the Moorish tribes (I think he means Berbers) “white Africans”. We can probably infer that they’re pale-skinned, if even Gibbon calls them white.

Not exactly. Gibbon is writing about the Roman era but he’s writing IN the Scientific Racism era; ‘scientific racism’ is a really long topic so I’ll just say that by Gibbon’s time the pseudoscience had progressed from using color words to describe the actual hue of a population, to using the same color words to describe what a population was ‘supposed’ to look like.

Gibbon is saying that these ancient North African peoples have facial bone structure, hair type, etc. that ‘proves’ a ‘common origin’ with, well, with Gibbon. You see echoes of this in how white Americans today apply race to pictures and in other situations, using complexion last.

“the artist and the deceased family have chosen…” I assume you meant “the deceased’s family” although I guess they are deceased by now.

Fixed!

l am sorry but Algerians are not black and most of them would not have been black even in ancient times there is far more fair skined people there than black and l noticed a contradiction in that you said that Romans were not out to assimilate people despite the fact that you mentioned emperor cloudis speech to the senate about the importance of asmilating the gauls anyway l like the your content l hope you keep uploading

This was a fantastic series, thank you! Aside from the skin colour issue (which is a big problem), Voshart made some other basic mistakes like making Nero a redhead and basing Pertinax’ portrait on a bust of Plautianus. The program he uses also appears to have difficulty modelling the sort of slightly curly hair common in Roman statues (for example of Augustus)

Concerning Elagabalus, that Emperor’s gender identity is also so… unclear I would not be entirely confident describing them in male terms

I think we can be sure he was biologically male.

Very true, but pronouns generally reflect gender identity rather than biology

We must remember our knowledge of Elagabalus comes from hostile sources, there’s no telling how much scandal is invented or exaggerated.

Suffice to say that the question is a minefield precisely because of Roman chauvinism. Within Roman culture, “this person thinks of themselves as a woman,” was about the most sneering thing you could say about someone you believed to be male. And Elagabalus, like some other holders of the imperial title, was short-lived, hated by many powerful men, and mostly written about posthumously.

So it’s functionally impossible to tell, 1800 years after the fact, whether:

1) Elagabalus was a transwoman, and as part of their attacks against her character, her Roman enemies exaggerated a grain of truth that they hated about her, or

2) Elagabalus was a cis man being lied about by Romans who hated him for something else unrelated to his gender and sexuality.

Either interpretation is at least broadly plausible as far as I can tell. Without a time machine- probably without something more than that- there’s just no way to know.

We view the distant past through a very narrow keyhole.

Latin is a gendered language. If the Emperor told people, “Call me ‘she'”, wouldn’t that have recorded?

From Cassius Dio:

“Aurelius addressed him with the usual salutation, “My Lord Emperor, Hail!” he bent his neck so as to assume a ravishing feminine pose, and turning his eyes upon him with a melting gaze, answered without any hesitation: “Call me not Lord, for I am a Lady.””

As Josh notes, the problem isn’t a lack of sources claiming that Elagabalus:

1) Instructed others to use she/hers pronouns

2) Dressed as a woman

3) Offered truly prodigious sums of money to any surgeon who could invent SRS seventeen hundred years ahead of schedule.

We have all of those, mostly (as I understand it) from Cassius Dio.

The difficult part is figuring out whether or not Cassius Dio made parts or all of this up. Because as I understand it, it’s exactly the kind of thing that a person who hated Elagabalus would say to destroy their reputation among future generations of the very chauvinistic, dare I say misogynistic and queer-phobic Roman society. We may speculate that Dio would have said it whether it was true or not, on the grounds that it was ‘scandalous.’

As I note in my previous comment, I suspect it’s impossible to prove the question one way or the other, or at least I know of no way to do so and doubt it can be done so long after the fact.

I asked about this last week, but:

last week:

> He then asserts his education in Rome and notes prominently his assumption of the toga virilis, the narrow purple stripe of which marked him as a Roman citizen

this week:

> this solid-white toga is the toga virilis: the distinctive formal dress of a Roman citizen.

Yes, this was something I also wondered. From what I have read the only togas with purple stripes were the toga praetextera of senatorial magistrates and (perhaps, this appears to be unclear) the trabea that equites used at formal events

Put simply Romans were triggered by outlandish forms of dress or religion, and could be very nasty about freedman status or ancestry, but skin color was a non starter prejudice wise.

I like Bret’s point that people of all ethnic backgrounds can feel connected to Rome, culturally if not lineally. A great many diverse people’s lived under Roman rule and participated in her politics and literature as citizens without giving up their previous identities.

I am not sure if this is a glitch on my end, but I can only see the second image for Voshart’s artwork, when I think there are supposed to be two. My apologies if this is purely on my side.

The problem with Voshart’s images is that the lighting makes the portraits look washed out, and it is difficult to tell the intended skin color.

I know what you mean by “the Queen’s Latin,” but I can’t stop thinking of the scene in Loki where Tom Hiddleston speaks impeccable and unmistakably Cambridge-y Latin to a (nicely diverse) bunch of TV Pompeiians.

The New York Times magazine is actually not a scholarly historical publication, and the idea that Italians (or Irish, or Jews, or whatever) were at one time considered “non-white” has been fairly thoroughly refuted by those who have studied the issue. If you want to say that those groups, and others, faced prejudice and discrimination, fine, but they always rode in the front of the bus.

Not quite. The Irish, for example, were regularly played against free blacks in northern cities before the Civil War, and Eastern and Southern Europeans were definitely considered to be inferior to those from around the North Sea.

It’s inarguable that they were integrated and assimilated quicker than blacks were (lack of obvious visual differentiation helps with that) but your last sentence considerably overstates their status in the early years.

You mean, there were separate seating sections in public transport for Irish or Italians? There were laws against Irish or Italians marrying people of British, German, or Scandinavian descent? There were separate schools for Irish and Italians? No, there were none of those things. Yes, they faced prejudice and discrimination, but analyzing their experience in terms of “whiteness” is no more useful than are concepts of “white” and “black” in Roman history.

If a restaurant puts up a sign saying “No blacks/chinese/irish”, we can infer that these groups were considered at least similarily repulsive by racist WASPS. The Irish may have been considered white, but they were not a part of what the people then considered American, just as they did not consider Tejanos, Cajouns, Mexicans and Germans to be Americans. Even though by any practical definition, these groups are white.

“No Irish need apply.”

There were academics claiming that didn’t have, a claim rebutted by a minor for a school project.

You seem to be arguing against the contention that the Irish and others had it as bad as blacks did. That is not the contention being made.

Not really, they’re arguing about the contention that they would fall within the same mental classification – the cultural construction of being “black” or generally “non white”. You could be treated badly for different reasons – racial bigotry isn’t the *only* form of bigotry.

The catch is that the category of “whiteness” is irreversibly and invincibly tied up with the category of “like us.” Implicitly, the person who gets to define what is and is not “white” is always themselves “white,” and gets to exclude from the category whichever groups they don’t like.

Because it’s not a statement about skin pigments. The pigmentation question is a red herring.

A very pale Japanese or North Chinese person whose skin tone is identical to a northern European is never “white,” they are (politely) “Asian” or impolitely a bunch of other words. Because what matters to the race theorists who invented the concept of “whiteness” as we know it isn’t literally what color your skin is. It’s common ancestry, or more precisely, the fiction of common ancestry. What matters is the belief that you and your people share a common small pool of ancestors whose natural increase has filled a certain area of land and made it theirs, and which is fundamentally unmixed with any other lesser groups from outside it.

See also Part IIIb of the Fremen Mirage collection on this site, if you haven’t already. 🙂

A bigoted nineteenth century Englishman or Anglo-American would certainly concede that the skin of an Irishman was literally colored white in the same sense that his own was. But he would immediately assert that the Irish were nonetheless a lesser breed of men, feckless and reckless and stupid and suitable mostly for brute labor and breeding too quickly and causing trouble. In short, a lot of the same stereotypes that in modified form have been wielded against African-American ‘blacks,’ but in a different form.

The Irish were not, during this period, part of the self-selecting and self-promoting club of “whites” who acknowledged only among themselves a presumptive right to be treated as equals and heirs to a common heritage worthy of respect and future dominance. They were still on the outside, looking in- and often enough, so were Italians, even as the self-designated “white” identity group of that time tried to claim the heritage of the Italians’ own Roman ancestors.

Simon Jester: You mean that in 19th century America, Irish or Italians were legally denied the right to vote? They were denied the right to stake claims under the Homestead Act? To sit on juries? No, none of those things happened. They were treated as having equal civil and legal rights in every area. There weren’t even any restrictions on their right to immigrate.

You mean, there were separate seating sections in public transport for Irish or Italians? There were laws against Irish or Italians marrying people of British, German, or Scandinavian descent? There were separate schools for Irish and Italians? No, there were none of those things.

There are none of those things now for blacks. By your logic, that means there are no such people as blacks.

Apparently the fact that people of pallor were also discriminated against as ‘other’ bothers a certain kind of theorist who prefers to see the world in black and white. Skin color is only one of several markers chosen for discrimination. National origin was very much such a marker in this nation of immigrants.

The problem is that in effect, “white” is both a word for a color and a word for a socially constructed racial/ethnic group invented by 18th and 19th century race theorists. The English language isn’t good at helping us parse what are in effect two homonyms.

This is why some people capitalize ‘Black’ and ‘White’ when referring to ethnic groups- but the ‘White’ ethnicity is particularly vague because it’s been subjected to Calvinball rules over the years. When it ceases to serve the interests of a certain kind of person to say “that group over there is not part of ‘Whiteness,’ then that kind of person ceases to do so. And within a generation or two, their descendants are choosing to forget that the discrimination ever happened, and acting as if the boundaries between ‘Whiteness’ and various forms of not-Whiteness loom large and fixed and reflect profound biological realities.

It really does depend on who you asked.

Even today the racial status of people from the Middle East, and of people with mostly European but very distantly removed African (or some other non-European) ancestry, are touchy topics with many conflicting models applied by different people.

There was no point where Italian or Irish people were universally (or anything close) considered non-white, but at the same time, neither were they near-universally considered white until recently. Some people viewed whiteness as a binary (one-drop rule – which, note, excludes many we might today consider white), others as more of a spectrum where one might draw the line in different places.

e.g:

“Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a Colony of [German] Aliens, who will … never adopt our Language or Customs, any more than they can acquire our Complexion.

“Which leads me to add one Remark: That the Number of purely white People in the World is proportionably very small. All Africa is black or tawny. Asia chiefly tawny. America (exclusive of the new Comers) wholly so. And in Europe, the Spaniards, Italians, French, Russians and Swedes, are generally of what we call a swarthy Complexion; as are the Germans also, the Saxons only excepted, who with the English, make the principal Body of White People on the Face of the Earth. I could wish their Numbers were increased. And while we are, as I may call it, Scouring our Planet, by clearing America of Woods, and so making this Side of our Globe reflect a brighter Light to the Eyes of Inhabitants in Mars or Venus, why should we in the Sight of Superior Beings, darken its People? Why increase the Sons of Africa, by Planting them in America, where we have so fair an Opportunity, by excluding all Blacks and Tawneys, of increasing the lovely White and Red?”

-Ben Franklin

Incidentally, the NY Times article linked above does claim that Italians were sometimes segregated alongside those we would consider black people:

“They were sometimes shut out of schools, movie houses and labor unions, or consigned to church pews set aside for black people. They were described in the press as “swarthy,” “kinky haired” members of a criminal race and derided in the streets with epithets like “dago,” “guinea” — a term of derision applied to enslaved Africans and their descendants…”

I’d go a step beyond that: White/Non-white isn’t a distinction that Romans would be able to understand, at least not in the way we do. If you asked a Roman about “white people,” I imagine they’d probably assume you were talking about people who were pale because they didn’t get sun (and/or used the makeup mentioned in the article) before assuming you meant their “base tone”. After all, whether someone was in the sun a lot could actually be a marker of something the Romans cared about.

And, of course whiteness isn’t just about skin; even if we accept that Italians and Poles and Jews are white today (which they weren’t a century or two ago!), Japanese people (for instance) have paler skin than many Caucasians, and nobody would call them white. Obviously, our sources don’t record any ninjas in Rome, but explaining that these pale- to tan-skinned people in Europe are “white” would feel as arbitrary and alien to Romans as separating French and German people from southern Europeans would to us..

Most likely, Romans would have interpreted distinctly “white people” to be Germans.

I would say whiteness is a sort of empty identity, even with all the privilege it carries. White culture is hard to pin down or define, though “Stuff White People Like” did it’s best to do so (really it was more what suburban bourgeoisie white people like). Really all of the colorist sort of terms have this problem, but being white I can say for certain whiteness is not an identity that means much to me though obviously it affects my life. I think whiteness has mostly existed as something defined against blackness in the Americas due to the history of slavery. Certainly African diplomats were not treated the same as “black people” in 1950s USA, and from what I’ve heard this is part of what drove some name changes in Black Americans as having the right name could get you better treatment in some cases.

African diplomats facing discrimination in the 50s/60s era US was a known and widespread phenomenon, most notoriously for diplomats driving through Jim Crow Maryland on the way back and forth between their embassies in DC and UN headquarters in New York, to such an extent that the mounting diplomatic humiliation for the US (at one point the USSR, with the support of several newly independent African countries, raised the issue to the UN as grounds to relocate their headquarters away from the US) was a not-insubstantial impetus for the federal government to throw its weight behind the struggle against Jim Crow at all!

What a pity the UN wasn’t relocated!

I think there is a clear color pattern, but I mean **hair color**. Most of them have black hair typical for Southern Europe and most of the humanity, really. Blonde and light brown hair common in Northern Europe is scarce.

Okay, so Jesus was not a (full) Roman citizen but a jewish citizen of Judea, a kingdom that was a client state of Rome. But he’s most likely the most striking example of whitewashing. In European iconography he’s usually depicted with pearl white skin. But he lived in sunny, arid climate and it was typical of his peers to have olive or tan skin. He was born there, not in Ireland or Sweden.

In East Asia he is depicted as East Asian. In Africa as African. The Byzantine images show him as Middle Eastern. People depict their God in a way they can identify with. What the real Yeshua bar Yosef looked like is immaterial.

One has to make allowances for how much racial variation the artists would see.

There are illuminated manuscripts where the bride in the Song of Songs has black skin — using India ink — and because she is beautiful, blond hair (in gold leaf) and blue eyes and her features are distinctly European down to a rather narrow nose even for a European, and the entire effect is that she looks like an anime extraterrestrial rather than an Earthling.

I’d like to see that. Are there any pictures of it online?

Sorry, it was in a book, and I don’t remember the title.

Is it this image? https://artmoscow.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/tumblr_inline_mwbz7d3dmd1rpr1t4.jpg

No, but that’s an excellent example of the type.

The plot of one surviving Hellenistic romance is a marital rift caused by the birth of a black child to two Greek parents. He is convinced of adultery: she protests her innocence. After much travail the truth is finally accepted by all: the child is black because a portrait of a noble Ethiopian king hung behind the marriage bed (it was a common belief that development was influenced by what the expectant mother saw). Everyone lives happily ever after…

The heritage of Rome can be widely claimed: the Ottomans were ‘sultans of Rum’ (as were an earlier Seljuk dynasty in Anatolia) and saw themselves as inheritors of East Rome – reformed by the true religion of course.

Huh. The one I heard was a white child born to the Ethiopian king and queen.

I must say . . . nicely done!

Here are the only three proofreading corrections I noticed as I read:

that is whose likely -> who’s

towns they live -> they livein OR in which they live

we know They very -> [add period]

Annnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnd . . .once again I am forced to use the reply function to “subscribe” to this thread. Trust me, I was careful to click that “Notify me…” box for the short list above, so I have no clue what’s going on. This is the 3rd or 4th week I’ve been forced to come back and do this.