This week we’re going to take a look at an aspect of contemporary international relations, rather than ancient ones. As has become somewhat customary, I am going to use the the week of July 4th to talk about the United States, or more correctly for this July 4th, the informal coalition (with formal components) of countries the United States inhabits and leads.

In some ways this is following up on a thread left hanging a couple of years ago when I commented briefly that I didn’t think the term ’empire’ effectively described the US position in the international order. And so this post will focus on what I do think is the US position in the international order, although the focus here is going to be somewhat less on the United States’ role within what I am going to call the ‘status quo coalition’ than it is on the coalition itself. Because the existence and breadth of this coalition is really unusual and thus remarkable; indeed it may be indicative of broader shifts in how interstate relationships work in an industrial/post-industrial world where institutions and cultural attitudes are beginning, slowly, to catch up to the new realities our technology has created.

Meanwhile, if you want to be part of the ACOUP Coalition, you can support this project on Patreon. We do, however, insist on a notional 2% of GDP support target that everyone ignores because, like NATO, there is no enforcement mechanism. If you want updates whenever a new post appears, you can click below for email updates or follow me on twitter (@BretDevereaux) for updates as to new posts as well as my occasional ancient history, foreign policy or military history musings, assuming there is still a Twitter by the time this post goes live. I am also on Mastodon (@bretdevereaux@historians.social) and BlueSky (@bretdevereaux.bsky.social), though I am most active on Twitter still (for now).

Balancing

But first, before we get into the coalition itself, I think it is a good idea to jump back to some of our international relations theory (particularly some neo-realism) to think about how countries ought, in theory to be behaving, based on how they have in the past normally behaved under conditions like those today. Mostly, of course, this is to point out that a rather chunky groups of countries are not behaving this way, which is the striking fact this essay is attempting to explain.

We’ve talked about the most common condition states find themselves in, interstate anarchy, before. In brief interstate anarchy is a condition in which there are many states operating in a state system which has few or no constraints on the use of violence. Because larger states can use the greater resources of their large size to impose their interests on smaller states, these conditions create a dog-eat-dog race in militarism where the only way for states to avoid becoming prey is to become the most effective predators. Such systems can be durable, if not stable, because everyone is doing this, creating a ‘Red Queen effect,’ where because all of the states are trying desperately to maximize security by maximizing military power, no one actually gets ahead.

But sometimes one or more powers do get ahead and begin to dominate the system. If it several larger powers doing this what we tend to see emerge are ‘balance of power’ systems. These too can be durable and even potentially stable (for a time), because of a key behavior that emerges among both the larger ‘Great Powers’ and smaller states: balancing. This behavior will be immediately familiar to players of strategy games, but we see it emerge in actual state systems too. The logic is fairly simple: weaker powers benefit from the relative independence that continued competition in the system gives them. Consequently, small powers want to avoid anyone ‘winning’ the game, since a singular winning power would be able to dominate and possibly absorb them.

The result of this behavior is the emergence of a ‘balance of power,’ facilitated by the fact that the powers in the system tend to align against whichever powers appear strongest, in order to check their advance. European politics from 1500 to 1945 followed this pattern, with shifting coalitions forming to contain any power or alliance that seemed on course to achieve a ‘breakout’ from the competitive system. Thus the anti-Habsburg coalitions of the 1500s and early 1600s, or the anti-France coalitions of the early 1700s, followed by balancing against Britain in the late 1700s and then balancing against France again in the aftermath of the French revolution, before the unification of Germany led to balancing against that power. The same behavior is visible in antiquity in both the Greek conflicts of 431-338 (balancing first against Athens, then Sparta, then Thebes and finally a failed effort to balance against Macedon) and the behavior of the Hellenistic successor states (and the Greek poleis) after Alexander’s death in 323 until Rome achieves breakout in the second century.

Balancing doesn’t always work of course: sometimes a large imperial power is able, by luck or superior resources, to achieve victory anyway, usually by winning a ‘war of containment’ – a war where a large balancing coalition attempts to cut a rising power back down to size. Rome successfully overcomes two (arguably three) of these on its way to achieving what we might term ‘hegemonic breakout.’ First in the Third Samnite War (298-290), the Romans faced down a grand coalition of Samnites, Etruscans and Gauls – essentially every non-Greek power not already part of Rome’s growing Italian empire.1 The Greek powers then try their luck inviting Pyrrhus in a similar balancing coalition, but also loses. The consequence of those wars was undisputed Roman hegemony in Italy: balancing had been tried and failed.

When balancing fails, the resulting system is hegemony. Once balancing fails, everyone’s interests suddenly recalculate in a diametrically opposed way. So long as balancing was possible, it was in most state’s interests to oppose the leading power in an effort to contain it; the moment balancing becomes impossible, it is suddenly in every state’s interest to support the leading power and align with it in the hopes of persisting as a client state and maintaining at least some degree of autonomy.

Of course the converse of this is that if the hegemon should stumble in some way, everyone’s interests all shift back to balance of power just as quickly. This is why some empires, especially very decentralized ones with lots of ‘vassal’ states, can decline for ages before failing very rapidly all at once. The collapse of the (Neo)Assyrian Empire in last three decades of the seventh century BC is a good example of this: one it becomes clear that central imperial power is weak, both subject peoples (Egypt, Babylon) and tributary neighbors (Medea, Persia) all turn on the former hegemon more or less all at once, leading to rapid disintegration.

These patterns of state behavior are quite well established and one could pile example after example of these general trends. They are, of course, not laws; states act in ways that deviate from their neo-realist ‘interests’ all the time. The people leading them make blunders, and miscalculations, stand on principle or make decisions for ideological reasons often enough. But in general when describing the pattern of decisions of a large number of states over a reasonably long period of time (say, three decades or so), the pattern holds pretty well.

Except right now.

The Failure of Balancing

Immediately after the end of the Cold War, we got the rough result we might expect: the rapid expansion of US influence as the United States – the sole remaining superpower after the collapse of the USSR – became a global hegemon and was thus in a position to rewrite the rules of international relations to suit itself. The End of History and all that. Many countries more consciously aligned with the United States and few more were made into high profile examples of what might happen to countries that failed to align with the new hegemon, being either ‘regime changed’ or isolated from the global economy. That part wasn’t the surprise.

What was surprising is that in the years that followed, a number of potential counter-weights to the United States did, in fact, emerge during what we may term the End of the End of History and yet balancing didn’t meaningfully reassert itself. One the one hand, two major revisionist powers emerged (Russia and China), with one of them clearly having the economic heft to potentially act as a peer-rival to the United States, to shield potential allies from the full brunt of American economic might and the nuclear umbrella to prohibit direct US military intervention in areas of high concern. Meanwhile a third possible power, the EU, emerged as ‘the dog that didn’t bark.’ A confederation of European states with enough economic power and population to immediately form a peer-competitor or at least containing coalition against US influence which simply opted not to.

Under the balancing model, we ought to expect a fairly wide range of countries to begin aligning with the potential competitors to the United States in order to limit American influence and constrain what the United States can do. A more multipolar world, they might well think, should offer great latitude for those countries to pursue their own interests.

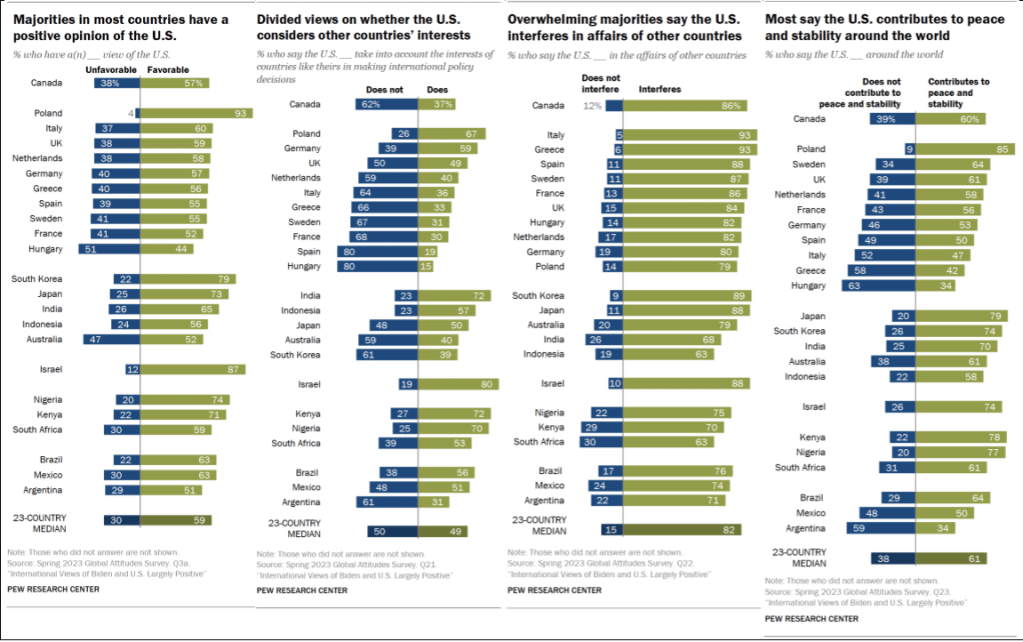

Instead, global opinion looks like this:

That data, from a June, 2023 study of global perceptions of the United States is pretty remarkable. Of course polling this this varies by the political moment and the administration in power in the United States and so the figures might not have been quite so favorable to the United States back in, say, 2018. Indeed, they were less favorable, but still net favorable, back in 2018 during the Trump presidency (which, regardless of your politics in the USA, was as a matter of data, less well regarded abroad) and before the War in Ukraine. But as interesting as the fact that the United States is viewed favorably in these countries – which to be fair is not all countries, but is a solid cross-cut of countries that are now or are likely to become major global power centers (sans Russia and China, in which it is impossible to do such polling) – is the odd cross-implications of the results.

To oversimplify the results a touch, we might say that the average respondent thinks that the United States is a meddlesome busy-body that only occasionally considers the needs of other countries…and that the United States is thus a force for good and peace and they like it very much, thank you. That is to say, respondents overwhelmingly thought the USA ‘interferes in the affairs of other countries’ and responses were profoundly ambivalent as to if the United States even tries to consider the interests of other countries, but despite that almost two-third of respondents concluded that the USA contributes to peace and stability and consequently had a positive view of it.

And that’s not just some polling data: globally we can see the failure of balancing. Despite the fact that the first real challenger to the US-led world order since 1989 has emerged in the form of the People’s Republic of China, the PRC has the same meager list of allies in 2023 that it had in 1953: North Korea. Russia likewise has a single European client state (Belarus); Russian friendship with Hungary has merely bought neutrality, not aid. The idea that BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) would constitute some developing-world coalition hasn’t really materialized either. While the rest of the BRICS won’t, for economic reasons, join the anti-Russian sanction regime, they also aren’t sanction-busting to any significant degree; even China’s support for Russia has been remarkably tepid. These are precisely the countries that ought to be eager to balance against the United States in order to open space to push their own interests.

Meanwhile, the United States’ list of allies is preposterous. Of the top 10 countries by nominal GDP – a decent enough measure of potential military capabilities – one is the United States and six more2 are close allies of the United States. Of the next ten, five more3 are formal US treaty allies, one is pointedly neutral4 and three more5 have either extensive economic ties with the United States, significant military ties with the United States or both.

Meanwhile the list of formal treat allies of the United States is expanding with the addition of Sweden and Finland to NATO.6 Likewise the formal American infrastructure in the ‘Indo-Pacific’ seems to be deepening, rather than declining, with a range of countries expressing at least some interest in joining AUKUS or at least an AUKUS-like deal with the United States in the region. France – which was more than a little wounded by the AUKUS pact, which unilaterally canceled a deal they had with Australia with basically no notice – nevertheless remained in NATO and remains a major component of the NATO-led support of Ukraine. This was, I should note, no sure thing – France pulled out of NATO’s main command structure (while remaining in the alliance) and only rejoined in 2009. Again, in a period where we might expect balancing against the United States, France has pulled closer, not further away, from Uncle Sam.

At the same time, it is not the case that all countries or even most countries are aligning with the United States. One of the very striking indicators of this is the lack of appetite in much of the world for sanctions against Russia. Most countries are both unwilling to sanction Russia and unwilling to sanction-bust in favor of Russia. A huge portion of the world, including nearly all of the ‘Global South’ (a term I dislike, but it will do here) are functioning non-aligned. But that very non-alignment is useful for the United States: if there is a large pro-USA coalition, a large non-aligned non-coalition and then isolated revisionist powers, that is a system where the American geopolitical vision remains the predominant one.

And I don’t think the non-aligned states are sleepwalking here: I think they know this and in many cases broadly prefer this outcome. You can see that preference reflected in the views of countries like Indonesia, India, Kenya and Nigeria in the chart above. They won’t back the United States if that incurs meaningful costs – these are developing countries that cannot afford grandiosity, after all – but they also won’t oppose the United States without a pretty substantial incentive. China’s efforts to ‘buy allies’ through the Belt and Road Initiative appear to have spent a lot of money buying roughly zero allies, globally. A whole lot of these countries – as you can see in the Pew polling data of some of the largest above – seem pretty content to let ‘Uncle Sam and Pals’ run the show, while they focus on economic and political development at home.

Balancing appears to have failed, without really even being tried. A handful of countries have tried to exploit what I think we can identify as balancing strategies. Israel retains studiously open channels with all of the major powers, while both Turkey and Indonesia have at least sounded out the idea of replacing US or NATO equipment in their militaries with Russian equipment. But where we might expect to see the emergence of a real anti-US-hegemony coalition, there is remarkably little appetite at present. Hungary is more pro-Russia than the rest of Europe, but not pro-Russia enough to send Russia tanks the way the rest of Europe sends Ukraine tanks. Viktor Orbán is, at most, only performatively pro-Russian, whereas the rest of NATO is actively pro-Ukraine in a way that bolsters American security policy. Instead, the ‘revisionist’ states, both large (Russia, China) and small (Iran, North Korea) largely stand both apart from each other and lack any kind of broader coalition that might reach other wealthy, industrialized countries with the will to actually make a challenge to the US-produced international system feasible.

For a revisionist power, this is a real challenge. Being isolated is no fun and successful efforts to overturn a leading power generally require either lots of alliances, diplomatically isolated the leading power, or both. So long as the United States sits ensconced in an alliance-system with dozens of the richest countries on Earth, the US-led international system is very difficult to revise. Just ask Russia how hard it is to move some borders in Europe.

And yet again, this is strange, because the countries arrayed, en masse around the United States ought to be some of the very countries – strong regional powers with big economies – that might benefit most from having the freedom to ‘revise’ the international order to suit themselves. And yet they don’t.

Why?

Ode to the Status Quo

I think the answer here is actually simple: the incentives for these countries have changed and now enough time has passed that they’ve realized it. The difference between Russia and France is, to be blunt, that the French know something the Russians haven’t learned yet (but are apparently in the process of learning right now). But let’s back up for a moment.

One of the very basic facts about IR theory is that, by necessity, it is developed using exemplars from the past. In particular, that means using mostly the pre-industrial or early-industrial past, if only because all examples we draw on must come before the present and we’ve only had lots of industrial societies interacting with each other for about a century and a half. We have centuries of balance-of-power politics in agrarian Europe, but far fewer years spent watching how post-industrial societies behave. And indeed, because social development is a process, we may not even yet be able to observe how mature post-industrial societies behave, because our institutions and mores may only slowly be developing into a stable shape. It took millennia from the development of farming to the emergence of the kind of large, extraction-based polities which became the standard large-scale organization of farmers. It is not at all clear that the societies we have now are stable, mature ‘post-industrial’ societies so much as some larval stage of transition to more stable forms.

But in any event, much of this theory was based on agrarian states or early industrial states. And one of the features of agrarian interstate relations was that returns to war outpaced returns to capital, which is a fancy way of saying you could get richer, faster by conquest than by development. Under those sorts of conditions, most powers were going to be, in some form, ‘revisionist’ powers because most powers would have something to gain by attacking a weaker neighbor and seizing their resources (mostly arable land and peasant farmers to be taxed). Indeed that basic interaction creates much of the ‘churn’ of interstate anarchy: everyone has an incentive to prey on their neighbors, creating the dog-eat-dog brutality of interstate interactions. The only countries without such an interest would be countries that were very small and weak, seeking to avoid being absorbed themselves.

But, as we’ve discussed, industrialization changes all of this: the net returns to war are decreased (because industrial war is so destructive and lethal) while the returns to capital investment get much higher due to rising productivity. In the pre-industrial past, fighting a war to get productive land was many times more effective than investing in irrigation and capital improvements to your own land, assuming you won the war. But in the industrial world, fighting a war to get a factory is many, many less times more effective than just building a new factory at home, especially since the war is very likely to destroy the factory in the first place. This was not always the case! The great wealth of many countries and indeed industrialization itself was built on resources acquired through imperial expansion; now the cost of that acquisition is higher than simply buying the stuff. War is no longer a means to profit, but an emergency response to avoid otherwise certain extreme losses.

So whereas in the old system, almost every power except potentially the hegemon, had something to potentially gain by upending the stability of the system, the economics of modern production means that quite a lot of countries will have absolutely nothing to gain from a war, even a successful one. Now that dispassionate calculation has arguably been true for more than a century; the First World War was an massive exercise in proving that nothing that could be gained from a major power war would be worth the misery, slaughter and destruction of a major power war. Subsequent conflicts have reinforced this lesson again and again, yet conflicts continue to occur. Azar Gat argues in part that this is because humans are both evolved in our biology (and thus patterns of thinking and emotion) as well as our social institutions, for warfare and aggression. We have to unlearn those instincts and redesign those institutions and this process is slow and uneven.

But we have started to learn and that has begun to influence state calculations. But note that those calculations are going to be fairly directly related to the level of economic development in a state: the more economic development, the more strongly the interest calculation tilts against war and towards stability.

At the same time, states aren’t unitary actors. Every state as conflict within it – conflicting visions of how the state ought to be run and so on. Those conflicts can of course become violent and boil over into broader conflicts which might end up involving even states who might not wish to be at war. Alternately, catastrophic state failure can produce refugee flows and other humanitarian disasters which can be destabilizing and trigger conflicts or convince states who do not want a war that nevertheless war is the ‘least bad option.’

That said, not all countries seem, in the post-WWII world (admittedly not the largest sample) to equally produce these sorts of externalities. In particular, rich democracies with robust protections for human rights and civil liberties tend not to. This isn’t to say such countries don’t have internal problems, but that these problems tend to be contained; they don’t generate refugee flows or cross-border insurgencies. Part of this is presumably that these tend to be strong states which can mostly maintain order in the borders and partly it is that the democratic nature of these states channels most internal divisions into peaceful democratic processes, while the protections for a range of human rights and civil liberties reduce the costs of ‘losing’ any particular round of democratic decision-making, incentivizing peaceful ‘repeat players’ in the game.

Please note how limited this argument is. It does not require that liberal democracies7 function perfectly, it does not require that they resolve all of their internal problems equitably or reach the right policy solutions or even that their internal political systems are entirely peaceful. It merely requires the greatest extremes of internal conflicts to be funneled into the political process. Given how rare it is for consolidated democracies to deconsolidate (to the point that arguing that it has never actually happened remains a live argument in political science; much depends on how one defines ‘consolidated’) it seems fairly clear that liberal democratic systems largely work in limiting violence in the political process and preventing it from either overturning the state or spilling over into neighboring states.

But all of that alters the incentives! For the inhabitants of those states, the status quo is actually really good. These are, after all, countries that are both rich and free, a distinction that we’re going to keep coming back to in this discussion. Such countries cannot get any richer through war, or any more free. Violent revisions to the status quo are thus only going to be bad for them.

Moreover they share all sorts of other interests because being rich and free creates a lot of ‘coincidences of interest.’ Rich countries generally prefer the free flow of goods, because their highly productive economies benefit from trade; they generally prefer the free flow of ideas because both their political and economic systems benefit. They tend to prefer stability in other regions, because they are prime targets for destabilizing refugee flows. Consequently, they tend to prefer the emergence of other rich and free countries, because those tend to be good trade partners who don’t generate massive refugee flows. That said, we don’t have a good grasp on how to create new rich and free countries and attempts to do so often fail.8

And the good news for these rich and free countries is that the current international system was largely the creation of one really big rich and free country (the United States) working together with a bunch of other rich and free countries, setting the rules the way rich and free countries like them. So the international system, embedded in organizations like the IMF, WTO, the World Bank and to a degree the United Nations, is institutionally structured to prefer the free movement of goods, ideas and capital and to discourage the revision of the status quo by force.

Rather than being simply an expression of American power (though they are that), those institutions are also an expression of the collective interests of this informal collection of rich and free countries, what we might call the status quo coalition.

The Status Quo Coalition

I think this idea of a status quo coalition which is both a key part of the structure of the United States’ geopolitical position but not exactly coextensive with it is important to understand. In the past I’ve struggled with how to describe the United States’ rather odd – and indeed, large to an unprecedented degree – global system of alliances and friendships. But I think the status quo coalition serves as the bedrock foundation on which that system is built. Not every United States partner or ally is a member of the status quo coalition, but I’d argue that nearly every rich and free country is a member and that nearly every member of the coalition is in turn, a US partner or ally. Indeed, the number of rich and free countries is small enough that we can simply list them, taking every country with a GDP per capita above $40,000 (PPP adjusted) and a Freedom House global freedom score above 70 (‘free’). I’ve also listed ‘memberships,’ mostly for the security arrangements these countries tend to have with each other; note that ‘BILAT’ indicates a bilateral security treaty with a member, usually (but not always) the USA; FVEY stands for ‘Five Eyes’ and AUKUS for, well, AUKUS.

| Country | GDP per capita ($PPP) | Freedom House Score | Memberships | Coalition Member? |

| Ireland | 145,196 | 97 | EU/Non-Aligned | Yes? |

| Luxembourg | 142,490 | 97 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Switzerland | 87,963 | 96 | Swiss Neutrality | No |

| Norway | 82,655 | 100 | NATO EEA | Yes |

| United States | 80,035 | 83 | NATO FVEY AUKUS | Team Captain |

| San Marino | 78,926 | 97 | BILAT (Italy) | Micro-Nation |

| Denmark | 73,386 | 97 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Taiwan | 73,344 | 94 | BILAT (USA) | Yes |

| Netherlands | 72,973 | 97 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Iceland | 69,779 | 94 | NATO EEA | Yes |

| Austria | 69,502 | 93 | EU | Official Neutrality (Yes?) |

| Andorra | 68,998 | 93 | BILAT (France, Spain) | Micro-Nation |

| Germany | 66,132 | 94 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Sweden | 65,842 | 100 | EU (NATO) | Yes |

| Belgium | 65,501 | 96 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Australia | 65,366 | 95 | FVEY AUKUS | Yes |

| Malta | 61,939 | 89 | EU | Yes |

| Finland | 60,897 | 100 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Guyana | 60,648 | 73 | Non-Aligned | No? |

| Canada | 60,177 | 98 | NATO FVEY | Yes |

| France | 58,828 | 89 | EU NATO | Oui |

| South Korea | 56,706 | 83 | BILAT (USA) | Yes |

| UK | 56,471 | 93 | NATO FVEY AUKUS | Yes |

| Israel | 54,997 | 77 | Complicated | Complicated |

| Cyprus | 54,997 | 92 | EU | Yes?/Non-Aligned |

| Italy | 54,216 | 90 | EU NATO | Yes |

| New Zealand | 54,046 | 99 | FVEY BILAT (USA, UK, AUS) | Yes |

| Slovenia | 52,641 | 95 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Japan | 51,809 | 96 | BILAT (USA) | Yes |

| Czechia | 50,961 | 92 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Spain | 49,448 | 90 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Lithuania | 49,266 | 89 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Estonia | 46,385 | 94 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Poland | 45,343 | 81 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Portugal | 44,707 | 96 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Bahamas | 43,913 | 91 | BILAT (USA, UK) | ? |

| Croatia | 42,531 | 84 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Romania | 41,634 | 83 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Slovakia | 41,515 | 90 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Latvia | 40,177 | 88 | EU NATO | Yes |

| Panama | 40,177 | 83 | No, but close USA ties | No? |

Naturally there are some quirks to a list like this. Some members – or arguably aspiring members – of the rich and free status quo coalition fall below my rather arbitrary GDP pet capita cutoff, Greece ($39,478/86GFS) and Bulgaria ($27,890/79GFS) most notably. Both countries are both NATO states and in the EU so they’re heavily involved in status quo coalition institutions, but theses are, in a sense free-but-not-rich countries, but they tend to move with rather than against the status quo coalition, so I think they mostly count as members.9 On the other hand are the rich-but-not-free countries, Hungary ($43,907/66GFS) and Turkey ($41,412/32GFS) which are also involved in status quo coalition institutions (both NATO, Hungary the EU) and it is of course immediately striking that these are the two obvious discontents with the Status Quo Coalition’s attitudes towards both the Russia-Ukraine and Syria crises. Not being free, it turns out, makes their fit with the coalition more awkward than it is for the countries that are free, but not yet rich. Yet both are, at least somewhat connected to the coalition despite that, often moving with it, complaints and all.

The other odd exception are countries in the Americas not named The United States and Canada. Guyana, the Bahamas and Panama all seem like they are both rich enough and free enough to be in the coalition and yet aren’t part of the formal institutions of it. This, it seems to me, is pretty clearly a product of proximity to the United States, both in that these countries already effectively have US security guarantees via the Monroe Doctrine (and so don’t need to be in something like NATO; that the United States would end up intervening in a major war in the Americas is almost a forgone conclusion, treaty or no treaty) and at the same time have felt themselves on the business end of American foreign policy in the region, which has often been profoundly unpleasant. Consequently, their relations with the United States are a much larger focus and the proximity of the United States constrains their options. We should, quite frankly, strive to do better by our neighbors than we have.

Nevertheless, while the core of the coalition is the United States and its European partners, tied together by NATO, that is not the whole of the coalition and most rich and free countries are part of it, regardless of where in the world they happen to be, with countries outside the North Atlantic often instead tied to the United States or other members in other ways.

Now one may well argue the coalition is just a figment of my imagination, but I’d argue that the renewed Russian invasion of Ukraine had demonstrated anything but. While many countries were willing to vote against Russia at the UN, the number of countries willing to sustain real economic costs by either supporting sanctions or sending meaningful aid to Ukraine was far more narrow and maps fairly well on the coalition as formulated above. The coalition action here is striking because none of the countries currently aiding Ukraine or sanctioning Russia had any sort of treaty obligation to do so. Instead, the coalition leapt to Ukraine’s aid with everything short of war (including free weapons, training, economic assistance and intelligence sharing) to defend the status quo, in which they are so invested. This is why, I’d argue, the response to the War in Ukraine and previously to cross-border conquests by ISIS was so much more intense than status quo coalition responses to other humanitarian crises, because it threatened a core component of the status quo, that territorial acquisition by conquest is not permitted in the international system.

What I want to stress here is an understanding of the coalition that it is not ‘countries in the thrall of the United States.’ Rather it is that this is a collection of countries which have developed, both economically and politically, in similar ways. Because of that similar development, they have come to have similar interests and values. And because they have already shaped the international system to favor those interests and values, they tend to act in concert in support of that international system, those interests and those values. I think this coalition, in some form, would continue to exist even without the United States and it would be a major force in international politics.

But of course the United States does exist, which brings us to…

The United States and the Status Quo Coalition

The United States’ position as ‘team captain’ of the status quo coalition is almost over-determined: it is the second largest bloc member by territory, has more than twice the population of any other member, the largest economy (six times larger than the next bloc member), one of the highest GDP-per-capitas, the most powerful military and is also ideologically one of the founders of the bloc, being both one of the origin points for modern liberal democracy and largely responsible for creating the bloc during the Cold War.

So while I think the coalition may well have emerged without the United States, it is no surprise that, the United States being a thing that exists, the coalition is often regarded (wrongly) by Americans and Russian propagandists alike as simply a tool of American Imperialism – a collection of smaller states huddled around Columbia‘s skirts. That reading is a mistake and it leads to misjudging how the coalition will act, because the coalition isn’t bound together by American power but by common interests and so behaves differently.

For the United States leading the coalition, the mistake is to assume that the members of the coalition are bound by American power (hard or soft), rather than by their own interests. That isn’t to say that US ‘soft power’ doesn’t matter. I think it matters quite a lot and is part of why the coincidence of values in the coalition is so strong. But when it comes to getting countries to act, interests are often much stronger. And the key interest at play here is a commitment to the status quo.

What that means is that United States leadership in the coalition (and consequently, US global leadership) is tied to the perception that the United States is, on net, a reliable guarantor of the status quo. What is going to shake the coalition is not outside pressure (which is, as we’ll see, a weak lever), but the United States as ‘team captain’ acting in ways that destabilize the status quo. This, I’d argue, is why the Iraq War seemed to shake the coalition so badly – it reflected an attempt to revise the status quo by expanding the coalition by force. It’s also why the Trump presidency’s promises of substantial revision to the United States’ place in the international system prompted concerns from the coalition as well.

But leading the coalition is good for the United States. For one, the vast network of interlinked institutions the coalition runs were built with US economic interests in mind and so tend to be favorable to them. Remember during the pandemic when all of the supply chains went haywire and prices rose dramatically? That’s what things would be like all the time in a less ‘globalized’ world – Americans would end up quite a bit poorer.10 This is a positive sum arrangement: the United States benefits a lot from the status quo it created, but other countries also benefit, which is what makes that status quo durable. But all of that free trade, free movement of ideas, free movement of capital and so on is facilitated by coalition institutions, like SWIFT, the IMF and so on.

Leading the coalition is also, frankly, good for American security interests. Alone, the United States is a power that a rising competitor (like the PRC) could imagine, if not defeating, at least excluding from substantial parts of the world. But ensconced in the coalition that becomes much harder, because challenging the United States risks trade agreements with France, or military action from Japan, or economic warfare from Australia, or diplomatic retaliation from Brussels. And remember for the United States, like every status quo country, our interest is not having a war in the first place. A system that thus raises the cost of challenging US leadership to the point that no country would attempt it is a system that makes a major war involving the USA directly a lot less likely, which is good, actually.

Not only does the coalition reinforce the American position by providing a ready suite of allies, it makes creating a revisionist coalition really hard because most of the best allies to have are already taken. Revisionist powers find themselves arriving at the pick-up basketball tournament to find that every player worth having is already only Team Status Quo, with only North Korea and Iran sitting on the bench waiting to get picked. And so long as the United States remains a reliable steward of the status quo, that is likely to remain the case, because the very things that make a country a good pick for your team – being a developed, highly productive country with strong institutions – make them more likely to instead join Team Status Quo.

For the voting public in the United States, all of this means it is necessary to come to understand that a lot of the good things we enjoy are as much a product of our reputation (again, see the polling above) as a reasonably reliable steward of the status quo as they are of US power directly. That in turn needs to influence political calculations about the costs and benefits of different courses of action: the cost for the United States of deciding to revise the status quo is potentially much higher than it seems, because it shakes the foundations of all of these mostly-invisible institutions that are in fact the root of a lot of the United States’ global power. Because the United States isn’t the king or general of the status quo coalition, it’s the ‘team captain.’ If it proves to be a bad team captain, the team may well choose a new captain, or disband altogether, with catastrophic implications for American interests.

From the outside, the mistake is to assume that applying a sufficient challenge to the United States and a sufficient degree of pressure will cause balancing to reassert itself and the coalition to fall apart. Both Russia and China have tried a strategy of trying to crowbar a wedge between the EU and the United States. I will not say such a thing is impossible, but it is pushing uphill: the community of interests is real and pushes back. Almost inevitably something, usually reminders of Russia and the PRC’s revanchist territorial claims, or some other international crisis, reminds everyone that they do, in fact, share interests and values. Instead of coming apart with pressure, the coalition solidifies with pressure because the pressure redirects everyone’s attention to those communal interests (rather than our petty squabbles, of which there are many). Since the community of interests is real, that pulls the bloc back together for collective action.

And that effect makes large-scale revisionist aims quite hard to achieve. To be clear, the most obvious sort of revisionist aims are shifts in territorial boundaries, but equally this goes for attempts to revise the structural of the global economy, for instance to de-dollarize it, or get many countries to move away from status quo coalition financial centers, or to get rid of the IMF and the World Bank, or substantially revise assumptions about freedom of navigation. For moves that require a critical mass of large economies in order to work, as with a decisive, global shift away from the dollar and euro, the problem is that there is a large bloc of big, rich countries that are largely uninterested in a revision to the economic status quo and who trade with everyone. You may want to be rid of the dollar and the euro, but it is going to be rather hard to convince the Germans.

That doesn’t make such revisions impossible, but it guarantees that accomplishing even minor revisionist aims is going to incur outsized costs. Of course the most striking example of this are the massive costs that Russia has incurred trying to shift its border to the west. But the PRC’s efforts to revise the status quo by shifting the governance of Hong Kong and pushing territorial claims in East Asia have also, slowly but surely, pushed the status quo coalition powers to begin pushing back and relations between the EU and the PRC seem to get frostier every month.

Moreover, the coalition doesn’t seem likely to go away. Once countries become rich and free, they tend to stay that way. Without a doubt there are politicians and parties in most status quo coalition countries that promise to pull their countries out of the coalition, usually on a nationalistic basis. In practice it seems to be hard (though surely not impossible) for such leaders to actually win elections and yet harder still once they’ve won elections to actually cleanly break with the fairly complex web of interlocking interests and institutions that tie them with the coalition. The experience of Hungary and Turkey’s ‘illiberal democracies’ provides something of a demonstration as neither country has yet managed to fully align away from the coalition.

That doesn’t mean I think countries will never leave, but it does mean that I think countries will tend to join the coalition at a faster clip than they leave. Global incomes, after all, are rising and seem set to keep rising. Remember: the interests that bind the coalition together are a product of economics as much as of politics. And unlike the zero-sum game of empire, where each empire has strong incentives not to let new powers join the ’empire club,’ economic development is positive sum. Rising incomes in the developing world are good news economically for the rich status quo powers as those developing economies ship out the raw materials rich economies require and buy the goods they make. Rising incomes in developing countries make them better trade partners as rising productivity means they both have more to export and more money to spend on imported goods. Moreover, as noted, high income, democratic countries tend to be stable and not create many problems (like refugee flows) which is also good news for the rich-and-free club.

Consequently, the status quo coalition wants to encourage other countries to be like it: rich and free. And quite a lot of countries are developing with that as a goal. So while I expect that here and there countries will, for internal political reasons, backslide out of the coalition, barring some major catastrophe it seems likely that the status quo coalition will grow, rather than shrink, over time. The big systemic risks here would seem, of course, to be nuclear war, another pandemic or climate change and it is no accident that the coalition countries tend to be quite worried about these. That said, it is worth remembering that even pessimistic climate change projections now expect that the impacts of climate change will cause global incomes to rise more slowly, not fall.11

As a result, I don’t think the coalition is likely to go away. As a historian, I’m always really reluctant in making Big Predictions and I think it is worth reiterating the caution that we do not know if this current arrangement is a mature or stable form of human organization in an industrial/post-industrial world. Most of the world isn’t really even fully industrialized yet and even the parts that are haven’t been long enough to make it clear that anything is settled in the long-term. And it’s not clear that, as global incomes rise, those rising countries will find the status quo as ameniable as the current crop of rich-and-free countries, especially since it sure seems like the ‘free’ part matters as much, if not more, than the ‘rich’ part.

At the same time, as a student of the history of war, the emergence of a durable coalition in international affairs with an interest in limiting at least some kinds of wars (because let us not pretend all of the status quo powers are pacifists) is an exciting development in the growing ‘Long Peace‘ that we may hope begins to indicate that humanity might at long last be outgrowing war.

So the status quo coalition isn’t necessarily the beginning of the End of History (Volume II: We Mean It This Time). But it is, I suspect, likely to be a durable component of the international system and, for as long as the United States remains a reliable steward of it, the foundation of American global leadership.

- It is striking but oh-so-typical of failed containment that one group holds aloof for what seem like cultural reasons. Rome only just wins the Third Samnite War – had the Italian Greeks joined in, the Romans probably would have lost. Instead, the Greeks of S. Italy opt to wage their own war (the Pyrrhic one), lose that one too and thus their independence. The refusal of key Greek states to join the balancing coalition against Philip II of Macedon is a similar sort of lesson: sitting out the Big Containment War can have catastrophic consequences for the folks sitting it out on the benches.

- 3. Japan, 4. Germany, 6. UK, 7. France, 8. Italy and 9. Canada

- South Korea, Australia, Spain, the Netherlands, and Turkey

- Switzerland

- Mexico, Saudi Arabia and Indonesia

- Tervetuloa and hopefully soon Välkommen! Assuming Google Translate has not let me down!

- American readers! ‘Liberal’ here means ‘with liberty’ not ‘of the political left.’ So a democracy with protections for core liberties and human rights is a liberal democracy.

- Most notably recently in Iraq and Afghanistan, but compare the successful creation of rich and free regimes – albeit it took some time – in East Asia (Japan, S. Korea, Taiwan) and Eastern Europe. It doesn’t always fail.

- Note for instance both are active supporters of Ukraine against Russia.

- Which is why even when then-president Trump revised NAFTA, he came up with a replacement that…was mostly just NAFTA (the USMCA). The deal was already very good for the United States, because we wrote it.

- ‘Rise more slowly,’ to be clear, is bad. It means more people in poverty longer than they needed to be. That’s bad. But it is a different kind of bad than global incomes falling (more people in poverty than yesterday), with different implications.

The paragraph immediately above the image” Via Wikipedia, a map of countries on Russia’s ‘Unfriendly Countries List’ ” seems to start halfway through a sentence. As it stands, you paragraph begins “ing to sanction-bust in favor of Russia.”

Great post, thank you!

Fixed

Regarding Azar Gat’s War on Civilization (a book I generally liked), I always found his section on biology to be the weakest. “Human sare hardwired for war because Darwin” is an evopsych-tier take that doesn’t remotely pass the rigor test of current paleogenetics. His reasoning is very much a lot of handwavibg without relying on, you know, actual genes (or even faint suggestions of purifying/positive selection on ancient human DNA). Ditto for his take on gender. I assume Gat himself isn’t to blame and largely drew on 1) the poor state of the art/sequencing data at the time where it was a lot easier to carve your just-so stories in what was available, and 2) the then-climate of constant prattling about the ‘human state of nature’ or ‘nature/nurture’ debates that current-day biologists have largely moved on from, despite what loudmouths on the internet would have you believe.

A much simpler explanation for the ‘maladaptation’ is that societies up to the very recent part followed warmongering cultural customs they inherited from their messy, distant history. No need to invoke ‘evolution’ or ‘genetics’ for this (and if you have to, for the love of God provide some *genes*)

I believe the “evolution” being invoked in the latter case is metaphorical. The reason societies up to the very recent past inherited warmongering cultural customs and not pacifist ones is that historically, warmongers tended to wipe out pacifists.

I’m not going to dispute the rigor of biological paleo-genetic argument, but genes do play a part in what makes us who we are.

My background is mental health psychology.

As such while there would be no argument from me that the question of nature versus nurture is the wrong question, nature and nurture are part of the human condition.The tendency to react with violence arises from evolutionary pressures to maximize reproductive success.

Fight, flight, and freeze are driven by emotions, which arise from changes in blood pH values that are mediated by beliefs that are triggered by thoughts that have underlying assumptions (the cognitive-behavioural model).

This means that confrontations trigger a fight, flight, freeze response.

So, from cognitive-behavioural perspective, fighting is one of the triad of responses humans have, and hence one can claim that they’re hardwired; but, with the large caveat that these responses are mediated by psycho-social factors.

This leads us as to how to understand our reactions to psycho-social stressors, and the human ability to rationalize our actions in concordance with our beliefs. This then into arena of the hard problem. How can our belief that we are conscience beings be reconciled with free will, where physics suggest that reality is deterministic where randomness is not equivalent to free will?

Philosophically, the resolution of this apparent paradox seems simple to me.

It depends on how you define the ‘self’ and ‘will.’ My identity, my ‘I,’ is not a disembodied ghostly floating unmoved mover. ‘I’ am a self-reflective process that performs operations we might loosely call ‘computational,’ even if the mechanics aren’t at all like how a computer would do things.

“I” have free will insofar as I am able to arrive at conclusions and act on them, but the definition of how “I” act upon the world is constrained by the laws of physics, because without physics there would be no material substrate on which “I” could exist. No gravity and magnetism and so on means no atoms, only void, and in the absence of the atoms, there would be no mind, no “I.”

No person who is not being willfully silly says “I wish to fly, but gravity causes me to fall if I jump off a ledge, therefore gravity violates my free will.” It is no less silly to argue that my decision as to whether to fight, flee, or freeze is influenced by, oh, blood sugar levels, and that this violates my free will.

I am large, I contain multitudes, and more specifically I damn well contain my own blood sugar.

Simon_Jester said, “Philosophically, the resolution of this apparent paradox seems simple to me.”

I think that the philosophers arguing over Dualism and Physicalism would disagree on how simple ‘I’ is.

Starting with Ryle describing Descarte’s ideas as a category mistake, along with Princess Elizabeth’s attack. Then the Behaviorist theory in turn attacked by the counter argument by Putnam, and the continuous back and forth by Searle, Jackson, and up to Chalmers etc..

We feel we have a self that we can call ‘I,’ which generates a very persistent belief that we can choose to calculate our best options, yet we live in a universe that appears to be deterministic.

If true, all our choices are inevitable.

Which is not to say I disagree with your approach, only that it is a delusion, or illusion, depending on how it is framed.

Violence is certainly part of human nature but organized mass violence isn’t. No one has an instinctual need to do a stranger’s bidding because they went to Westpoint. It takes a lot of training to get humans to be good soldiers because it doesn’t come naturally to us. But it takes zero training to get a human to run from danger because that’s what we naturally want. Human mass violence would likely be more like raiding and vendettas without militaries making the violence more efficient.

The style of fighting you’re describing is only as old as the Bronze Age. Prior to that, we appear to have fought in the same way as other apes: sneak attacks, melting into the environment when things got hairy. Low- to moderate-lethality raids, in other words.

Of course, this sort of supports your point. Modern warfare is so different from anything our ancient ancestors dealt with that evolution simply hasn’t had time to keep up. Even assuming that First Systems Warfare is instinctive, or at least has some basis in evolutionary history, we’ve only been obliterating towns via high explosives for a few generations. Sure, it’s a serious selection pressure, but it’s hardly had time to work.

Again, though, it’s worth pointing out that this is seriously steel-manning the argument. A more rational view of human evolutionary history would focus on farming, since that’s what the VAST majority of humanity did. (Interestingly, farmers engaged in First Systems Warfare quite late–see Scotland and England. So at least First Systems Warfare and farming are not mutually exclusive. Rolling barrages and farming, however, very much are.)

War Before Civilization by Lawrence H. Keeley

Raids are not lower in lethality than wars.

The nature of the wounds was different. An arrow or blade inflict dramatically different types of trauma on the human body than high explosives. A system adapted to handle one cannot be assumed to be adapted to the other.

The fight-or-flight instinct is also going to be affected (assuming there is an evolutionary component to this, which is dubious). First Systems warfare doesn’t involve the “stand still while people attack you” aspect that a shield wall or linear combat with muskets requires. This would result in different selection pressures, the former favoring “flight” and the latter favoring a suppression of this reaction.

How are you defining First Systems Warfare? Wikipedia speaks of First Generation warfare as all warfare based on infantry formation fighting, from antiquity until the end of rank and file musket battle in the 19th century. The defining feature of which is “stand still while people attack you”

“first system of warfare” comes from earlier blog post here: https://acoup.blog/2021/02/05/collections-the-universal-warrior-part-iia-the-many-faces-of-battle/

Ah, completely different term. Thanks.

You don’t need to point to specific genes to talk about evolution. Darwin came up with natural selection without any idea what genes even were, and could make predictions like “an orchid with this shape implies a moth with a match proboscis”.

I don’t think it’s an extraordinary claim to say that aggression is one of the basic human impulses; it’s common elsewhere after all, including in our nearest relatives the chimps, and seems influenceable by taking testosterone.

And I know Gat would say that warmongering is more than some arbitrary custom. As our host has said, it’s often a response to personal or social incentives (not always the same).

(One of the bigger problems with evopsych is that much of the purported rational calculus works just as well as either “evolved mechanisms” or people responding rationally to incentives on the fly.)

Genetics is not the be-all, end-all of evolution. First, we don’t know exactly how genes become organisms–transcription is not a simple process, epigenetics does something but we’re still not 100% sure what, and environmental factors influence final outcomes in various ways (there are a bunch of genes that determine height, for example, but early diet also heavily influences it).

The idea that evolutionary arguments necessarily must include genetics is disproven by the fact that we can determine trilobite evolution. Cetacean studies have shown that genetics, morphology, and biochemistry all produce similar clades, so morphology is no less valid than genetics.

There ARE reasons to believe humans are hard-wired for violence. For example, other apes engage in deliberate violence, often using simple tools, to remove competing groups from territory. In paleontology the argument “These other members of the clade have X character, ergo this member of the clade probably does despite us not seeing it” is a valid argument. It’s a fairly weak argument, and must be discarded when any data are present, but it IS a valid argument.

Further, human males are built to absorb a surprising amount of punishment. And we are, quite frankly, expendable. One man can produce a fair number of children, while women typically max out at one a year (“A flower must never fly from bee, to bee, to bee” as the king of Siam said in the musical). Typically masculine traits, such as strong jaws, allow for men to take harder punches before we suffer damage, and allow us to deliver harder punches. This is again weak evidence, but corroborates the cladistic argument.

All that said….it’s SUPER easy to read what we want to read into such evidence. And evolution doesn’t care about what “should” happen, only what DOES happen. There are multiple breeding strategies that would reduce the signal from warfare-based selection. None of this addresses women, either, which is not insignficant.

And honestly this is the wrong way to look at things anyway. 90% or more of humanity was farmers for the vast majority of our history. THAT is where we should be looking for selection pressures. And the same things that make one good at fighting make one good at subsistence farming. It’s not easy, and it was extremely common to damage one’s self; being able to take a few blows before you were incapacitated was perhaps more important in farming than in warfare. In war you’re exposed to violence occasionally; most of the time you’re bored out of your mind, marching and mending and setting up camp and suchlike. Farming using Medieval (and up to inter-World War) methods, on the other hand, presented opportunities to be damaged every single day.

This illustrates a deep flaw in Evo-Psych: What you choose to look at must be VERY carefully chosen, because it’s going to determine the answer you get. If you ask “Are humans adapted to combat?” you’ll get one answer. If you ask “What pressures influenced recent human evolution?” you get a totally different one.

Yeah, it’s a ridiculous assertion. Humans are hardwired to put on uniforms and march in ranks? So much of military training is about getting humans to go against their natural instincts. A poorly trained army is one where humans still act like humans. They run from danger and not towards it, they loudly question ideas that don’t make sense, they punch a rude stranger that yelled at them for not making their bed.

The defining characteristics of warfare are not putting on uniforms and marching in ranks. Marching bands do both; are they therefore engaged in warfare? Probably no man did either while serving William the Conqueror, Alfred the Great or Ivar the Boneless; does it follow that none of them ever fought a war?

War is an act of co-operative violence. As the master said: “War therefore is an act of violence to compel our opponent to fulfil *our* will.”

For creatures to be capable of war they have to be capable of cooperating with each other, and of violence against rivals. That is all.

It seems absurd to say that humans are in any sense naturally incapable of either of those things.

You’re arguing against a rhetorical flourish I was employing.

Can you therefore make your point more explicitly and with less poetic licence, so that I might more clearly understand it?

Humans are obviously not hardwired to put on uniforms and march in ranks as such, but they are clearly hardwired to make sacrifices and take risks for other members of their ingroup, and they often define their “ingroup” by dress. Just look at any teenage clique, where you will find they all dress alike, be it goth or punk or metal or whatever, or at any office where management has declared a “dress down” regimen: after a brief period of experimentation, all the men dress alike (commonly dress shirts without ties and chinos, possibly with sports coats) and so do all the women. In most military units, the “uniform” (as in consistent and universal) dress is dictated from on high, but it still works to make the individual soldiers recognize each other as members of their ingroup.

This is an interesting post. I’m by default inclined to the “human nature has not changed, nor will the universal dynamics of international relations” stance. But industrialization is in fact a change that could have the scale to affect such universal dynamics.

One issue here is that using “freedom” as an explanatory variable is tricky. “Freedom” is not a trivial concept, nor a scalar; attempts to rank “freedom” on a single scale are fraught, because it has multiple dimensions and the different dimensions trade off between each other. In particular, the rhetoric of freedom is a major part of the propaganda of the US, both internally and internationally, and also of particular US political factions (in different ways). Thus, high-profile public ratings of different countries in terms of “freedom” are likely to be just as much propaganda creations as valid measurements of a real underlying variable; and in particular, “freedom” in the propagandistic sense is largely correlated to “how much US propaganda institutions like you”. Therefore, using these rankings to try to explain countries’ support of a US-dominated international order is rather circular; countries that vocally oppose the US are likely to suffer in the rankings just for having done so.

Looking over the Freedom House rankings in somewhat more detail, I’m comfortable saying they are substantially ideologically influenced. As an example, Germany outscores the US in every category, including “freedom of expression”. This is despite the fact that Germany explicitly bans various forms of Nazi-related political expression (a fact that’s even noted in the writeup). By the tone of the writeups, it seems that the official suppression of disfavored political expression counts as a positive in their “freedom of expression” category; the US gets dinged for “hate speech and misinformation” on social media. This in particular doesn’t necessarily bear on the conclusion re: the status quo coalition, but it suggests that the Freedom House rankings might similarly be subordinated to ideological preferences in other ways.

They’ve always been strongly ideological, they were strongly ideologically influenced (on the right, broadly) during the Cold War too. That said, I think it’s probably impossible to rate “freedom” scores and *not* be ideologically influenced- how you think about and define freedom is inherently ideological.

Of course it’s highly ideological. But I do think it’s gesturing in the right direction enough that a 99, a 70, and a 40 tell you that places are usefully different from each other in the sort of ways you’d care about for this kind of index.

I think it helps to think about Freedom House in a neutral sense rather than a morally loaded sense. They’re rating societies by how well they conform to broadly, Anglo-American liberal values (in the sense that both, say, Barack Obama and Ronald Reagan were liberals). A society with a 90 rating is going to conform better to American liberal values than a society with a 30 rating. Is it going to be a *better* society to live in? Sure, if you hold to liberal values- if you’re a communist, or a nationalist, or an Islamist, probably not.

On the face of it, you are “free” to the extent that other people can not arbitrarily force you to do things you don’t want to do. People banned from praising Adolf Hitler, for example, are likely to feel their freedom has been noticeably infringed only if they sometimes wish to do so.

I might point out that Germany has PR parliamentary democracy at every level, and consequently a lot of vaguely centrist coalition governments. The United States, on the other hand, has presidential democracy at every level, and perhaps the most exclusive two-party system in the democratic world.

The median American voter, then, is probably a lot more likely than the median German voter to find himself being ordered around by a government controlled by some extremist he disagrees with.

So Freedom House are probably absolutely right.

Germany has more freedom of speech than the US de facto. The fact that Holocaust denialism is illegal here is a lot less relevant than things that libertarians do not care about but remain important.

For example, in the US, any kind of political organization in a safe state (i.e. most of them) is expected to engage in flattery of the governor to an extent that recalls Early Modern absolute monarchies; in New York, if your explanation of a problem (say, the inability to build infrastructure or housing) was “Andrew Cuomo is bad,” while he was in power, it was treated with about the same scorn as if youd propose, federally, that the US ritually put the constitution through a shredder.

This matters, because most modern-day dictatorships don’t restrict free speech in the same way Cold War communist states did. Before Xi brought back this system, the system in the PRC was that you could be critical of the state as long as you didn’t engage in any organized attempt to change things: “Hu is lying about X” was fine, but “let’s boycott Y” would get your social media account suspended. As in Ancient Greece per Bret’s How to Polis series, tyranny is not especially formalized in such a system, but everyone knows what you can and cannot say.

And then there’s how anocracies work. Press freedom organizations working in places like the Philippines, Iraq, or Mexico are a lot less worried about formal state censorship than about gangs, local magnates, and private armies (in Iraq, Israeli human rights activist and student Elizabeth Tsurkov was just confirmed to have been kidnapped by a militia, not by the state). Hence the point about social media hate speech.

The question of what flatteries you have to make to advance your position through the political machine is not that closely related to the question of what things you are forbidden by force of law from saying. “Freedom of expression” relates substantially to the latter, not really at all to the former. There is no free speech right to have your political program taken seriously, even if it’s a good and a wise one.

Likewise, if you really have local militias or other extragovernmental armed forces attacking people for what they say, that is a very different issue, and a much worse issue, than having hate speech on social media. Bringing up the former in the context of the latter seems like a dodge.

It’s not “advance through the political machine” – it’s “have literally any ability to organize.” For the same reason, there are independent attempts to quantify the levels of civil liberties in a polity that incorporate organizational things like workers’ ability to unionize.

And the issue of hate speech online dovetails into SWATting. Is it the same as militias in Iraq? No. Should it count as a restriction on speech? Yes.

The trouble with Americans is that they tend to be completely focused on government even as private companies build their own fiefdoms. Force is force, whether you are forced to do something by law or by he will of an unaccountable corporation matters little. Freedom of expression in law is useless if you don’t have ways to use this right, and so on. If you read the constitutions of Soviet states for example, you’ll find many freedoms that were actually more theoretical than practical. The law is not everything.

The heyday of corporate private power in the United States was the latter 19th and early 20th centuries. Unionization of workers was opposed literally by deadly force. People who wouldn’t sell out to monied interests would suffer a variety of “accidents”. It would be inconceivable for anything like that to happen in the modern USA; getting banned from Twitter isn’t even in the same league.

Suffice to say that while private corporate power isn’t at the highest point in all of American history, it can still be ‘too high’ or ‘trending upwards’ without being at ‘literally the Gilded Age’ levels.

Yes, and a state where dissidents are tortured or murdered by extra-governmental paramilitaries will typically have a much lower Freedom House score than one where all that happens is that dissidents are abused without consequence for being [slurs] on social media.

You’re absolutely right that there are matters of degree here! But we’re still measuring essentially the same thing. Namely, the question of how much force does a country’s power-holders use to “kick down” at those who might seek to break their hold. Since not all the power-holders are politicians, not all the force that gets used will always be aligned with a political party. And it certainly won’t all be governmental.

Compared to the US, Germany

* has much higher legal certainty. The US justice system is more capricious, being heavily influenced by money, pressure groups, public opinion etc. This matters because the threat of being of sued in the US limits freedom of expression, e.g. in the case of American anti-discrimination law, which can be positively Orwellian. In contrast, a Holocaust denier in Germany can usually avoid punishment unless he is very foolish, because it is clear what the legal boundaries are.

* is (obviously!) more conformist. If you have strange views, your prestige (often in the form of an academic credential) matters more than in the US. Debates are more often held with the expectation of consensus-building rather than exchanging ideas. This results in an intellectual climate where many participants are erudite, but also hostile to innovation. I find American intellectuals far more interesting than German ones, for mainly that reason.

On the other hand, Germany is not the only country on the list with a higher Freedom Score than the US, and may not reflect the only way to “game the system” to get a higher score.

I don’t mind banning the speech of Nazis (which holocaust deniers usually are) because Nazis don’t respect other people’s freedom of speech when they are in power, so other people don’t have an obligation to respect their freedom of speech when they are out of power. But, that said, I strongly disagree with the point of the first part of your comment:

“Germany has more freedom of speech than the US de facto. The fact that Holocaust denialism is illegal here is a lot less relevant than things that libertarians do not care about but remain important.

For example, in the US, any kind of political organization in a safe state (i.e. most of them) is expected to engage in flattery of the governor to an extent that recalls Early Modern absolute monarchies; in New York, if your explanation of a problem (say, the inability to build infrastructure or housing) was “Andrew Cuomo is bad,” while he was in power, it was treated with about the same scorn as if youd propose, federally, that the US ritually put the constitution through a shredder.”

When other people heap scorn on you, that’s an expression of their freedom of speech, not a violation of yours. I don’t have much patience or respect for the kind of conservatives and right-wingers who think they’re being censored when their opponents say mean things about them. I don’t see why I should respect that line of argument more when it’s coming from someone who is personally neither conservative nor right-wing.

“Andrew Cuomo is bad” was not a conservative take. At all. Note how for years after Me Too, activists didn’t even try pushing it with him, even though once the first complaints surfaced, it became clear that everyone who was around him knew. Only when he was weakened due to corona did things seriously start coming out.

The issue with safe states is not at all ideological. The problem with New York isn’t that you’re expected to be ideologiclly liberal; it’s that you’re expected to flatter the monarch, so to speak. And then it’s the same everywhere else the same party expects to stay in power indefinitely – California, Massachusetts, Texas, Alabama (think how Roy Moore’s pedophilia only became public knowledge when he was running for Senate – and the people who made this knowledge public subsequently received death threats), what have you.

““Andrew Cuomo is bad” was not a conservative take. At all.”

I didn’t say it was. My point was that “It’s a limitation of freedom of speech if saying certain things will lead to people heaping a lot of scorn on you” reminds me of the stance of many conservatives. Again, when other people heap scorn on you, that’s an expression of their freedom of speech, not a violation of yours.

The critical point of difference here is whether the bad consequences for freedom of speech are “top-down” or “bottom-up.” Freedom of speech, like all individual rights, is much more about protecting an individual’s right to “punch up” than their right to “punch down” or even “punch sideways.”

This is precisely because punching up is normally very difficult when it isn’t protected by law. The role of individual rights in the social order is to bind elites and protect the masses, and at the same time to force the masses to show restraint rather than going on pogroms against minorities.

If criticizing Andrew Cuomo results in Andrew Cuomo using his extraordinary political power to retaliate against you, that undermines your ability to speak freely.

If criticizing a penniless orphan with cancer results in everyone else independently deciding to shun you, that’s not a diminution of your freedom of speech. That’s just you doing something very unpopular.

The difference is that Andrew Cuomo has the power and influence to stack the deck in his favor, artificially persuading people to help those who flatter him and ruin his critics. The orphan does not have this kind of power, and so other people’s reactions to what you say about them is going to be more authentic.

Freedom of speech is about protecting you from the artificial consequences of offending powerful people in society or of trying to speak on behalf of a group “official” society would prefer to silence. Not about protecting you from the natural consequences of making yourself very unpopular.

Unfortunately, this creates obvious gray areas, and there’s a lot of “where do you draw the line” questions in play.

Even if you’re right, I don’t think this refutes Dr. Devereaux’s argument. If Freedom House’s definition of “freedom” is narrow and ideological, that just makes it more noteworthy that so many countries share it.

I also don’t think there’s a compelling alternate take on “freedom” that states outside the coalition or on its margins have embraced. The two rich non-free countries Dr. Dx names- Hungary and Turkey- really are less free in concrete, non-ideological ways; their autocratic leaders have suppressed political dissent, taken various hostile actions toward ethnic and religious minorities, reduced the legal rights of LGBTQ people, etc. Russia and the PRC are likewise. There’s no alternate freedom here, unless you stretch the concept to include “freedom from Western scolding” or “freedom from living near Uyghurs.”

Huge missed opportunity to call it the status quoalition…

As an American broadly critical of the US’s international goals and actions, this was a really informative read! One thing I wish you addressed more was the way it’s *also* in the US/coalition’s interest to have poor and unstable second-tier countries with extraction-based economies that export raw goods (food, textiles, oil, minerals) at much lower prices. There’s also the way that developing countries getting richer so they can buy *our* exported stuff is at odds with the long history of racism in our foreign policy.

Otherwise though this was definitely a great post, I’ll have to keep the failure of balancing in mind when thinking about international politics in the future

As I recall, natural resource extraction makes up a much larger fraction of the of the economies of Australia, Canada and Norway than of the United States. Do you consider them to be kept in the position of “poor and unstable second-tier countries”?

It might be better to look at this the other way round. Unstable countries are poor because violent competition between people struggling for power destroys human sources of wealth; leaving them with nothing valuable except natural resources that no politician or warlord can destroy.

> As I recall, natural resource extraction makes up a much larger fraction of the of the economies of Australia, Canada and Norway than of the United States. Do you consider them to be kept in the position of “poor and unstable second-tier countries”?

They have large primary sectors *for developed countries*, but they are developed, and have been since before the current international financial system existed. The typical claim here is that the liberalizing “structural adjustments” imposed by the IMF and World Bank destroy infant manufacturing sectors by forcing them to compete with far more efficient firms in developed countries.

Then why didn’t they destroy the infant manufacturing sectors of Canada, Australia and Norway by forcing them to compete with far more efficient forms in developed countries?

(I feel sure there will be an answer to this. Every conspiracy theory can come up with an explanation for everything. But I am curious.)