This is the continuation – the first of several – of the fourth part of our series (I, II, IIIa, IIIb, IVa, IVb, IVc, IVd,IVe, V) looking at the lives of pre-modern peasant farmers – a majority of all of the humans who have ever lived. Last time we discussed the survival requirements (in food and textiles) of a peasant household as well as what different levels of material comfort beyond just survival might look like.

This week, we’re going to take those figures and begin comparing them to production, modeling out our farmers and their ability to grow the food they need to survive and perhaps a bit extra to sell, trade or gift away to get other things they want. We’re going to split this into two parts: this week we’re going to model out farmers assuming they own effectively infinite land. Then next week we’re going to revise those assumptions in light of the very small farm sizes we actually see in our sources. And after that – because we’re not done – we’ll move to discussing other kinds of labor in the household, like food preparation, cleaning, textile production and so on, to get a really thorough look at household labor.

In particular, on one of the persistent myths I wanted to address in this series is the idea that modern workers work more than ancient or medieval peasants, something that we’ll see is simply not true. Finally, note that while we’re going to be modeling farming subsistence here, we’re not going to get into the gritty details of how that farming was done; if you want to read about that, we already have a series on it just for you!

But first, if you like what you are reading, please share it and if you really like it, you can support this project on Patreon! While I do teach as the academic equivalent of a tenant farmer, tilling the Big Man’s classes, this project is my little plot of freeheld land which enables me to keep working as a writers and scholar. And if you want updates whenever a new post appears, you can click below for email updates or follow me on Twitter and Bluesky and (less frequently) Mastodon (@bretdevereaux@historians.social) for updates when posts go live and my general musings; I have largely shifted over to Bluesky (I maintain some de minimis presence on Twitter), given that it has become a much better place for historical discussion than Twitter.

Works and Days

The origin point for nearly all of those “you work harder than a medieval peasant” memes and articles is Juliet Schor’s The Overworked American (1993). The argument has been debunked quite a few times, so I won’t belabor the point here. Schor bases her estimates of medieval working hours on a 1935 article by Nora Kenyon,1 and an unpublished article by Gregory Clark,2 and in both cases ignores the authors’ careful efforts to distinguish between total days worked and instead just cherry-picks the lowest number, even as the authors caution that those numbers likely don’t represent someone’s total employment. Kenyon notes a set of day-laborers working 120 days per year which makes it into Schor’s work, but Kenyon’s final suggestion that the normal annual working year was 308 days does not, for instance. I can’t get at an unpublished article, but Clark has continued to write on the topic and in his 2018 “Growth or stagnation?” presents a detailed argument for a 250-300-day work-year with no sense that this is a revision of his previous positions, leading me to suspect similar cherry-picking as with Kenyon.

In short, Schor’s works is quite shoddy and we shan’t rely on it.

Now part of the complication there is that for the European Middle Ages, across so much area, what we see is a lot of confusing evidence – statutory minimums, required labor on a lord’s land and so on – which may or may not represent a full working year. What we don’t typically get is someone just telling us how many work days were in the agricultural calendar. But as you may recall, we’re anchoring this discussion in the Roman world and in a rare instance where the ancient evidence is better, Roman agricultural writers just straight up tell us how many working days there were in a year on the Roman agricultural calendar: 290 (Columella 2.12.8-9). He allows 45 days for holidays as well as inclement weather and another 30 days for rest immediately after the crop is sown, to recover from the difficult labor of the final plowing.

The medieval work calendar is not meaningfully different. As noted above, Both Clark and Kenyon end up with similar working-day estimates from the medieval evidence as Columella’s figure. The medieval number is probably slightly lower: the medieval religious calendar might have around 45 feast days but workers might also be expected to spend Sundays in religious observance, which might pull the work-year down to around 270 total working days, plus or minus.

By all evidence, those working days were both less rigid but also longer than modern working hours. On the one hand, peasant farmers are essentially self-employed entrepreneurs, making their own hours. They can arrive in the field a bit late, sometimes leave a bit early. It was certainly common in warmer climates for workers to take a midday break (a siesta) to avoid exhausting themselves in the hottest part of the day. I will say, anyone who has done functionally any outside work in a warm climate will recognize that a midday break can allow you to work more than just pushing straight through the heat of the day because you tire more slowly.

So on the one hand the work hours are somewhat flexible. On the other hand as functionally anyone who has ever worked on a farm or spoken with someone who has will tell you, the working day in absolute terms is long, essentially starting at sunrise and running to sunset. And this is certainly the implication we get from our sources. Because of atmospheric refraction, there are actually slightly more than 12 sunlight hours per day on average (it’s around ~12.3 or so, depending on latitude), though this of course varies seasonally. The bad news for our farmers, of course, is that the shortest days are in the winter when the labor demands are lower. While festival calendars feature events throughout the year, it is not an accident that major festivals in a lot of pre-modern agrarian cultures are concentrated in late Fall, winter and early Spring. For the Christian calendar, that includes things like All Saints Day (Nov 1), Martinmas (Nov 11), the regular slew of December holidays as as the holidays of the Eastertide in early spring. For the Romans, you have major festivals like the Parentalia and Lupercalia in February, the Liberalia in March, the Cerialia in April and the Saturnalia in December.

So in practice the average maximum working day might actually be a bit longer than 12 hours, but we should account for breaks and general schedule flexibility. We might assume, for comparison, something like a ten hour work day. By that measure, our peasants probably put in somewhere between 2,500 and 3,000 working hours per year. By contrast, your average ‘overworked American’ has 260 working days a year, at eight hours a day for just 2,080 hours.3

So to answer the question: no, you do not work more than a medieval (or ancient) peasant (despite your labor buying a much higher standard of living). But there’s more complexity for us to draw out here in the structure of peasant labor, so we need to go back to our model and start working through some implications.

Farming Time

As I noted previously, we’re going to anchor our model in the Roman evidence because I know it best and here the Roman agricultural writers – the agronomists (Cato the Elder, Columella, Varro and Palladius) – equip us with a lot of useful information, especially Columella. These fellows are writing guidebooks on how to run large estates – how to be good at being the Big Man – but the information they include, especially Columella, helps illustrate a lot about the labor and subsistence structures involved. As we’ve noted above, Columella already computed a standard agricultural work-year. We could convert that back into hours, but we don’t need to, because Columella does all of his labor calculations in working days.

The temptation here is to run our model on a single crop – wheat or barley – but that is a mistake. Columella himself suggests an estate (again, he’s thinking big farms) split between a wide range of crops, with primary plantings in wheat, a variety of legumes, along with turnips (and other root vegetables), barley, and so on. Our peasants will almost certainly do the same. There are a few reasons for this variety.

First, even from antiquity, farmers were aware that some crops exhausted the soil more rapidly or differently than others. They don’t fully understand it, but even Columella notes that some improve the land and others ‘burn’ it. And he is basically correct: lupines, beans, vetch, lentils, peas and such he regards are improving the land, while things like wheat reduce its fertility and some crops (he notes flax) put substantial strain on it (Columella 2.13). Of course farmers need those demanding crops, so rotation is necessary and was practiced since antiquity.

Second these crops all have different planting and harvesting timings. (Winter) wheat is planted in late Fall, barley in early winter, chick-pea can be sown in January or February, sesame in October, and so on and so forth (Columella 2.10). That’s important because planting and harvest create huge peaks in labor demand and our farmers want to try to flatten those spikes out a bit. If you plan nothing but wheat, you’ll never have enough labor to get all of it into the ground and then harvested again during the ideal calendar windows to do so.

Third is the perspective of risk management. All of these crops are vulnerable to different problems. A dry year will savage your wheat crop but barley is less bothered by dry conditions. Crops tolerate early frosts, high heat or low heat and so on differently. Pests that afflict one kind of crop may not afflict others. So by splitting your fields between different crops, you reduce the risk that any one problem will wipe you out. Remember that our peasants are not looking to maximize profit, but to minimize risk.

So our farmers are likely going to rotate a number of different crops. Now as to crop rotation, we often teach a fairly simple story of technological advancement from ancient two-field rotation systems (with half the land fallow) to medieval three-field systems to early modern four-field states (with the fallow largely replaced by fodder and grazing crops). And that description is more or less true but as always complexity abounds on closer inspection. As Pliny the Elder notes, the true maxim of farming was quid quaeque regio patiatur – “whatever the region permits.” For the Romans, we find attestations of two-field, three-field and continuous cropping systems where, in the latter case, extensive manuring was used to keep land under continuous cultivation,4 all depending on the local conditions: the richness of the soil, the availability of water, the local value of crops (and thus the affordability of manure) and so on.

For the sake of simplicity, we can think with three crops, wheat, barley and some legumes (in this case, vicia faba, the broad bean, for instance), though we also have to remember that about a third of our fields will be fallow in any given year. The legumes here are actually pretty important (and Columella seems to think a wheat-focused farming operation would sow wheat and legumes in even quantities, even while fallowing some of the fields, Columella 2.12.7-8) because they are nitrogen-fixing (technically, they have nitrogen-fixing bacteria) and so serve to maintain the fertility of the soil.

Different crops, of course, will have different productivity, demand different amounts of labor and so on. And here, as a reminder, since I am leaning on Columella, my background calculations are taking place in Roman units: modii (8.73 dry liters) and iugera (0.623 acres).

Wheat, Columella reports, was sown 5 modii to the iugerum (that is, it takes five modii – c. 43.5 liters or c. 1.2 bushels – to provide enough seed for 1 iugerum (0.623 acres) of farmland), and requires 10.5 days of labor. Columella (2.9) has barley sown 5 modii to the iugerum but Varro (1.44.1) suggests 6 modii to the iugerum; barley being more tolerant of bad conditions requires according to Columella only 6.5 days of labor for 5 modii for one iugerum. For beans, Columella says between 4 and six modii to the iugerum with 7 or 8 days of labor. That said, Columella’s labor-time estimates have left a number of things out – particularly threshing – and has probably somewhat underestimated plowing time5 so we need to account for that working time too. M.S. Spurr figures the wheat figure should be 14.25 days per iugerum, while Rosenstein estimates 19.5 days when accounting for the missing tasks, though note that we have not included a lot of background maintenance like maintaining tools or structures – this is purely the work for individual crops in individual fields.6 If we apply a similar under-count-adjustment to the labor requirements for barley and beans, we might come to a seed-and-labor-inputs estimate that looks like this:

| Wheat | Barley | Beans | |

| Land Area | 1 iugerum (0.623 acres) | 1 iugerum (0.623 acres) | 1 iugerum (0.623 acres) |

| Seed Required | 5 modii (43.65L, 1.2 bushels) | 6 modii (52.38L, 1.44 bushels) | 4 modii (34.92L, 0.96 bushels) |

| Labor Required | 14.25-19.5 days | 9-12 days | 10-14 days |

Now we have to think about how much labor our families have to throw at this problem. You will recall that last time we proposed three sample families, the Smalls, the Middles and the Biggs. How much farming labor do they have?

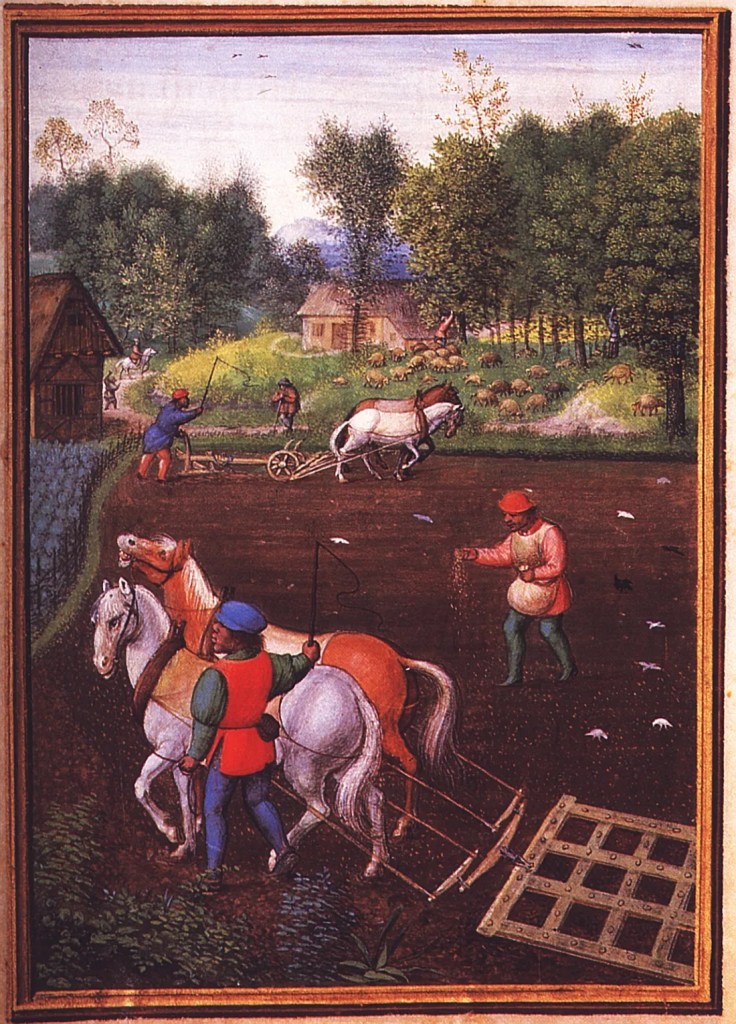

Labor patterns in these households were gendered, but not infinitely so. As Paul Erdkamp notes, in Roman artwork – and in my experience this pattern continues in medieval artwork – we do see women doing farming labor, but typically only in periods of peak labor demand (like the harvest, which has to be done relatively rapidly) or in households where some sort of misfortune has resulted in severe labor shortages.7 So for the sake of calculating the farming labor ‘backbone’ we may – for now – exclude the women of the household, though I want to be clear that women did farming labor when necessary and absolutely were not going to sit around starving to death if all of the men were gone. That said, as we’ll see in subsequent parts of this series, the women of the household were by no means idle: there was a ton of necessary work beyond farming required to sustain the household and they’re doing most of it.

Columella’s labor calculations are for large estates utilizing slaves or paid workmen and so assume fully fit adult males, but our actual peasant households are more varied than that. We ought to assume that each adult male (none of our model families has any very old men, so we don’t need to factor for that) is supplying a full unit of labor, 290 working days per year. Children under 6 or 7 or so are not going to be performing the main labor tasks, but we might figure that males in their late teens (16 and older) are providing something like three-quarters the labor-power of a fully grown adult and younger sons (10-15 or so) perhaps half as much. Based on those assumptions, our labor ‘backbone’ (which, again, would be supplemented by the women and girls of the household when needs be) looks like this:

| The Smalls | The Middles | The Biggs |

| Mr. Smalls (M. 40) 290 Work Days Per Year | Mr. Middles Jr. (M. 27) 290 Work Days Per Year | Mr. Matt Biggs (M. 43) 290 Work Days Per Year |

| John Smalls (M. 14) 145 Work Days Per Year | Freddie Middles (M. 16) 217.5 Work Days Per Year | Mark Biggs (M. 16) 217.5 Work Days Per Year |

| Mr. Martin Biggs (M. 28) 290 Work Days Per Year | ||

| Total Labor: 435 work-days | Total Labor: 507.5 work-days | Total Labor: 797.5 work-days |

Assuming then that land is no object (which it obviously is, but that’s next time’s problem) and a roughly even split between wheat, barley and beans, we might suppose totals for land under cultivation for each family very roughly like this (trying to get reasonably close to maximum labor employment without going over):

| The Smalls | The Middles | The Biggs |

| 11 iugera of wheat (c. 185 days) | 12 iugera of wheat (c. 202 days) | 20 iugera of wheat (c. 338 days) |

| 11 iugera of barley (c. 115 days) | 12 iugera of barley (c. 126 days) | 20 iugera of barley (c. 210 days) |

| 11 iugera of beans (c. 132 days) | 12 iugera of beans (c. 144 days) | 20 iugera of beans (c. 240 days) |

| Total: 432 work-days 49 total iugera (16 fallow), 30.5 acres | Total: 472 work-days 54 total iugera (18 fallow); 33.6 acres | Total: 788 work-days 90 total iugera (30 fallow); 56 acres |

Now, I see you there in the back, your hand already shot straight up because these farming areas are way, wildly bigger than what we’ve said typical peasant farms look like and yes, that is true. We’ll see how land scarcity factors in the next part, which is why I want to reiterate that this week’s analysis is not complete in itself for the obvious reason that very few peasants have unencumbered ownership of anything close to farms this large. Even a farm of 49 iugera would mark a household out to be very rich peasants. Nevertheless, we have to establish a baseline somewhere and this is a reasonable spot to do it.

Our next question has to be what these farmers might expect to get out of all of that work.

Farming Yields

As a rule, farming yields in the pre-modern are discussed not in terms of productivity per-land-area but rather in seed yields: for a given dry measure of seeds planted, how many of the same dry measure of seeds (because those are the tasty, edible parts of these plants) do you get back? So they are expressed in figures like 4:1 which means for every one modius/dry liter/bushel sown, four are harvested.

Yields were extremely variable, both season to season and region to region and our evidence for historic yields is often frustratingly limited or difficult. This is complicated by the fact that we cannot use modern farming yields to estimate, because hundreds or thousands of years of selective breeding have come to mean that modern crops are not identical to their ancient forebears and often have substantially higher yields, even if you used ancient farming techniques. As Theophrastus notes, ἒτος φέρει, οὒτι ἂρουρα, “the year bears [the harvest], not the field” (Theophr. Caus. pl. 3.23.5) by which he means seasonal variation was greater than regional variation: a bad year on excellent farmland was often worse than a good year on marginal land. That extreme level of variability makes charting an ‘average’ difficult. That problem is further intensified by the fact that our sources for antiquity often distort reported yields for rhetorical purposes – suggesting unreasonably low yields for crops they do not favor, or reporting absurdly high yields to simply the richness of specific regions.8

The best compilation of the evidence for ancient yields, which includes some comparative evidence for early modern and medieval crop yields, is in P. Erdkamp, The Grain Market in the Roman Empire (2005), 34-54.9 Yields on grains (like wheat and barley) might vary a lot, from as low as 3:1 on poor land in bad years to as high as 12:1 or more on good land in good conditions. Regional variability here is substantial: Spurr notes that in medieval Italy, hilly, marginal lands often yielded 3:1 or 4:1, while more typical flatter farmland might yield 5:1 or 6:1, but Sicily – with unusually good farmland – seems to have often yielded between 8:1 and 10:1. The general range for these yields is fairly consistent through the pre-modern evidence, improving modestly over time (so we might expect significantly, but not radically, higher yields for a peasant in 1500AD as compared to 1500 BC).

For our farmers, we probably ought to pick a pretty modest yield: our peasants probably don’t have the very best land available (the Big Man will have tried to get control over that) and also don’t have unlimited access to things like manure to really push yields at the upper end. On the flipside, our peasants are probably not on entirely marginal land (rocky ground, hills and so on). So we might propose something like a range of 4:1 to 8:1 to get a sense of the range from a bad year (4:1 yield) to a good year (8:1). For what it is worth, regions with very high productivity don’t tend to necessarily have richer peasants – they tend instead to have higher taxes.

Now of course some seed must be held back from each harvest to provide the seed for the next planting, but our yield ratios neatly contain this information. So while at a 4:1 yield, four modii/liters/bushels are harvested, one of those goes straight back into the ground, so the net yield is 3 units of whatever dry measure we’re using; at 8:1, the net yield is 7 units. In this case that works out to the following productivity per iugerum:

| Wheat | Barley | Beans | |

| Land Area | 1 iugerum (0.623 acres) | 1 iugerum (0.623 acres) | 1 iugerum (0.623 acres) |

| Seed Required | 5 modii (43.65L, 1.2 bushels) | 6 modii (52.38L, 1.44 bushels) | 4 modii (34.92L, 0.96 bushels) |

| Labor Required | 14.25-19.5 days | 9-12 days | 10-14 days |

| Gross Harvest | 20-40 modii | 24-48 modii | 16-32 modii |

| Net Harvest After Seed | 15-35 modii (~131-305L, 3.6-8.4 bushels) | 18-42 modii (~157-367L, 4.3-10.1 bushels) | 12-28 modii (~105-244L, 2.9-6.7 bushels) |

With that in hand, we can loop back to our chart above and calculate the range of net harvest after removing seed for next year that our model families might expect from their farming listed above.

| The Smalls | The Middles | The Biggs |

| 165-385 modii wheat | 180-420 modii wheat | 300-700 modii wheat |

| 198-462 modii barley | 216-504 modii barley | 360-840 modii barley |

| 132-308 modii beans | 144-336 modii beans | 240-560 modii beans |

That’s a lot of modii. But of coruse now we have another problem to account for: the modius is a dry measure. Pre-modern farmers mostly reckoned in dry measures because it was easy to measure but it is awkward for us because these crops, once harvested and put in sacks for storage, do not have the same density (that is, mass per unit volume) or calorie density (that is, calories per unit mass) as each other. So we need some way to convert these figures to our subsistence measure we developed last time which was kilograms-of-wheat-equivalent.

For wheat that’s relatively easy: threshed wheat has a density of roughly 6.72kg per modius (about 770 kg/m³), so a modius of wheat is 6.72kg of wheat equivalent. For the other two, we need to convert from a dry measure to a density to a calorie value to convert back to wheat equivalent. Barley is a little less dense than wheat, roughly 6.465kg per modius (740 kg/m³) but much less calorie dense – just ~2,160 calories per kilogram compared to wheat’s 3,340.10 So a modius of barley has roughly 13,960 calories in it, making a modius of barley just 4.17kg of wheat equivalent. A modius of beans (vicia faba) is about 5.43kg and contains about 18,842 calories, making that modius 5.64kg of wheat equivalent.

That neat exercise should also tell us something about farming strategies. A single iugerum, planted with wheat, yields (net after seed) between 100 and 235kg of wheat equivalent. Planted with barley, it takes much less labor and is more tolerant of bad (particularly dry) weather, but yields only between 75 and 175kg of wheat equivalent. Planted with beans, it consumes an intermediate amount of labor, helps the soil recover and provides unique and necessary nutrition – man cannot, as a matter of biology, live on bread alone – but provides only 68 to 158kg of wheat equivalent. A farm that finds itself strained – especially if the limit is land and not labor -might focus more and more heavily on barley (if it is very dry) or especially wheat at the expense other crops in order to maximize the yield per land area (which in turn means employing more labor). Keep that in mind for next time when we start factoring in land scarcity.

However for now, let’s head back to our tables and now factor our yield ranges into wheat equivalents to a get sense of how they stack up against our subsistence requirements (I’m rounding some of these figures off, so there may be some imprecision in the table):

| The Smalls | The Middles | The Biggs |

| 165-385 modii wheat 1,110-2,590kg wheat equivalent | 180-420 modii wheat 1,210-2,820kg wheat equivalent | 300-700 modii wheat 2,020-4,700kg wheat equivalent |

| 198-462 modii barley 825-1,925kg wheat equivalent | 216-504 modii barley 900-2,100kg wheat equivalent | 360-840 modii barley 1,500-3,500kg wheat equivalent |

| 132-308 modii beans 745-1,740kg wheat equivalent | 144-336 modii beans 810-1,895kg wheat equivalent | 240-560 modii beans 1,350-3,160kg wheat equivalent |

| TOTAL: 2,680-6,255kg wheat equivalent | 2,920-6,815kg wheat equivalent | 4,870-11,360kg wheat equivalent |

If we compare to the subsistence and respectability needs of our households, we can make a few observations. First, given maximum labor employment and no land scarcity, even in modestly bad years each family clears its subsistence needs (though only the Smalls clear their respectability needs). In something like an ‘average’ year, the Smalls produce around 187% of their respectability needs, the Middles 155% and the Biggs 150%.

If labor and not land was the limiting factor in peasant agriculture, we ought to expect our peasants to live quite well. Of course even a casual glance at the first post in this series will warn against jumping to that conclusion. After all, by ignoring – so far – land scarcity, we’ve put our families on enormous farms by pre-modern standards, between 30 and 60 acres, more or less. But we know from the evidence that while our families might have the ability to farm 30-60 acres, the typical size of an actual smallholder farm was closer to 3-6 acres than 30-60; a farm of even something like 15-25 acres might mark a family out as ‘rich’ peasants. And above we can see why: a family on 20 or 30 acres probably has enough land to get close to or even reach its respectability basket without engaging in any kind of tenant or wage labor. Instead, that family may have so much land it can afford to rent out what it does not farm itself.

What we have done here so far is essentially simulated very rich peasants, which is well enough but as we’ve seen, rich peasants represented only a fairly tiny minority of the peasantry. In practice, households with as much land as above would be likely to begin repurposing some of it for things like livestock, vineyards or orchards – things with a lower per-acre calorie yield but which might provide greater food variety or market value. As you can tell from looking at the relative balance of labor- and land-intensity for crops, the “mostly grains” strategy is going to be a direct response to land scarcity rather than abundance.

Rather, as we’ll see, most families will have nowhere near enough land to match either their labor or their subsistence demands, which in turn will provide some of the wedges that the Big Men and the broader society will use to try to turn that ‘surplus’ labor to their own ends.

And that, of course sets up where we must go to next: how this model changes – and goodness, does it change – once we start thinking about land scarcity and tenant farming.

- “Labor Conditions in Essex in the Reign of Richard II,” Economic History Review 4.4 (1934)

- “Impatience, Poverty and Open Field Agriculture” (1986). I can’t obviously interrogate an unpublished article, but Clark revisited this topic later in “Growth or stagnation? Farming in England, 1200-1800” in The Economic History Review 17.1 (2018)

- If you are thinking, “wait, but don’t have nearly so many day-off festivals, how do we end up with fewer work days, the answer is weekends. The medieval Christian peasant gets one day off in seven; the Roman peasant got one day off in eight (the nundinae; the Romans count inclusively and so call their eight-day week the ‘Nine days’). You get two days off in seven and that adds up very quickly.

- On this, see Spurr, Arable Cultivation in Roman Italy (1986), 117-132. Various rotations discussed in Plin. HN 18.187, 191; Varro Rust. 1.44; Columella Rust. 2.9.4, 2.9.15, 2.10.7.

- On these points, see Rosenstein, Rome at War (2004), 68, n. 25.

- Rosenstein op. cit., Spurr, “Agriculture and the Georgics.” In Vergil, edited by I. McAuslan and P. Walcot, 69-93. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Erdkamp, op. cit., 87-90.

- On this, see Erdkamp op. cit. 34-46.

- Erdkamp’s major intervention is to pry ancient historians away from the extremely pessimistic yield figures for wheat given by Columella. As Erdkamp notes, Columella is an outlier compared to our other sources and his yield figures seem exaggerated to favor his argument (he argues for vineyards over grains as a cash-crop).

- This difference is following Foxhall and Forbes, “Σιτομετρεία: The Role of Grain as a Staple Food in Classical Antiquity” Chiron 12 (1982), 42-47, who argue that the combination of the heavier hull of barley with relatively inefficient hulling available in antiquity would mean that significant less of the nutritional value of barley as harvested would make it into the final barley flour; they assess a ‘discount’ of about a third, which I’ve followed here.

I don’t really have much to say about this, but I am fascinated. I do find these agricultural history ones the posts I think I just directly learn the most from.

“The Overworked American (1993). The argument has been debunked quite a few times, so I won’t belabor the point here. Schor bases her estimates of medieval working hours on a 1935 article by Nora Kenyon,1 and a 2018 article by Gregory Clark2”

I, uh, don’t think it’s possible that a 1993 book bases its estimates on a 2018 article?

It’s interesting that to meet even just subsistence a family needs more than double the land they’re likely to actually have. I suppose most of it is owned by the local Big Man, but that’s a remarkable disparity – the local Big Man (Big Men? Would you expect more than one local Big Man?) probably owns more land than all the local peasants put together. Though some peasants have a lot more, so maybe only roughly comparable.

Yeah, that graph got tangled in editing, I’ll revise it.

Found the problem. The wires that crossed is that Schor cites a 1986 unpublished paper by Clark which doesn’t seem to exist in any available format – because it was unpublished – so I had bounced to Clark’s 2018 revisiting of the topic to get a sense of what Clark’s own view is and then tangled up the two G. Clark articles, citing the one I had when I needed to indicate that Schor relies on the one no one can get or check or verify.

I can’t find any suggestion in the later article that Clark’s position has ever changed, so I strongly suspect the same sort of cherry-picking going on here, but it is possible that in this unpublished phantom paper that no one can find Clark advanced an unusual view which he then subsequently and quite quickly (as quickly as the early 1990s) abandoned.

Or as it was unpublished, it had uncorrected errors(typoes perhaps?) in the figures?

Or maybe it’s unpublished because Clark realized he’d made some serious errors…

Snopes: “In an email to Snopes, Clark, now a distinguished professor emeritus at the University of California, Davis, said he arrived at this number by comparing records of annual and day laborers.

Clark said he no longer agreed with the methodology used to calculate the estimate attributed to him in Schor’s book, but had since come to support a significantly higher estimate. In a paper published in the Economic History Review in 2018, Clark expressed support for an estimate closer to 300 days a year, representing a working year similar to those recorded in the 19th century.

Clark described his current methodology as being based on living standards. One of the classes of evidence he has used as a proxy for living standards is the amount spent on supplies required to feed workers while they were on the job, as recorded in medieval employers’ accounts.

If medieval workers worked only 150 days per year in certain periods, according to Clark, then the relative amount employers spent on rations during those periods should be roughly half what was spent during later periods on workers who, thanks to improvements in record-keeping, are securely known to have worked 300 days a year on average.

Instead, Clark pointed out, the relationship between the amount spent on workers’ food and the amount spent on their daily wages remained surprisingly stable from 1350 to 1869, something Clark has taken as strong evidence that workers in medieval England on average worked roughly the same number of days per year as workers in the 19th century.”

https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/medieval-peasant-only-worked-150-days/

It would have been helpful if you could state what you mean by “patriarchy”, in addition to “traditional agriculture” (as plough use was not typical for all parts of the world).

I suspect plough use was good for women in the long term. If men do not have to work to spread their genes, they will do something else. They will engage in more violence, create all-male societies that terrorise their women, and steal the proceeds of their labour. A woman can spend all day preparing a meal and still eat last. By far the best place to be a woman today is the Western world with its history of labour-intensive agriculture, which has granted women the highest social status among earth’s cultures. The worst place is the Islamic world, and interestingly Africa where men were less needed for women to sustain themselves. The greater independence of African women, e.g. in enterpreneurship, has not resulted in them being treated especially well. For that men need to be civilised.

Did you mean to imply that Schor based here 1993 work on a 2018 article? I’m guessing some editing made this a bit awkward.

This was addressed by Dr. Devereaux in a previous comment, but what happened is that Schor cited a 1986 work by Clark that Clark never published, and Dr. Devereaux couldn’t obtain a copy of that manuscript. Thus, when trying to figure out what Clark was actually saying and whether Schor’s citation represents his work accurately, Dr. Devereaux had to look at a 2018 paper by Clark on the same subject, and some wires got crossed I guess. The matter is, as of this writing, clarified in the original article text.

Your comment on women doing farm labor illustrates a pernicious thread that runs through these discussions: The definition of “labor”. For example, for a long time in England the poultry (ie the chickens) and the dairy (ie, butter, cheese, that sort of thing) were the domain of women. Men would help with the poultry–they were not welcome in the dairy–but these were things women did. The money also traditionally went to the women in the house (though you’d have to be a particularly stupid wife to let your family starve and not put your money towards the problem). In addition, the gardens were largely the domain of the women of the household. Again, men would help (particularly with things like providing manure, building walls, and felling trees), but by and large the garden was women’s work. And by “garden” I mean “place where everything not a grown in fields or foraged from the woods was grown”–some of these gardens could be substantial!

The question arises: Does this count as “farm labor”? I’ve done poultry, and it absolutely is work! Same with gardening–on a scale capable of providing even substantial flavoring for a household, it’s work! But it’s all too common for our sources to exclude this from “work” because it was women doing it.

On the masculine side, the issue is things like hunting, cattle raiding (common along the Scottish boarder), and the like. It all provided food, income, and stability to the family (provided you don’t get caught poaching or rustling), but can be excluded from “farm work”.

It’s also worth noting that calculating work time by daylight hours only gives you a lower boundary. Anyone who’s been involved in agriculture knows that while a lot of the work is sun-up to sun-down, there’s a lot that also includes staying up late. If you have animals you’re up when they need you, including foaling/lambing/calving, if they get ill/injured, if they get attacked, if they need driven to market, etc. For fields you’ve got a bit more flexibility–at the cost of plants being unable to tell you if there’s a problem–but there are still times when you’re working by moonlight. If a wall fails you need to get it back up, before the pigs, or wild animals, or other people get to your fields. Even Medieval peasants could do some things with drainage, and sometimes that meant staying up late. Some tasks need to be done in a certain timeframe, and you just had to do it, even if it meant staying up all night (harvest, thrashing, certain parts of building projects, etc). And remember, this was a culture where fire was central to life; this means that fire was an omnipresent risk. Then there’s the less-savory aspects, such as poaching–we should not pretend that these didn’t exist merely because they were illegal! So those work hours, again, represent the lower limit of what these peasants were working, not an upper limit. (Similarly, an 8-hour day is a lower limit–ask anyone in the trades!)

“(Similarly, an 8-hour day is a lower limit–ask anyone in the trades!)”

This was my first thought when I read the beginning of the post that calculated work hours. The average American is not working five 8-hour days a week and then going about their personal lives the rest of the time. Part of why we consider ourselves overworked is the seeming omnipresence of overtime or second jobs. Gallup found that in 2019, the average American full time worker worked 44 hours a week at their primary job (though it’s fallen to about 43 hours since then), which would bring the annual total to 2,288. Still less than the peasant, of course, but noticeably closer.

Looked at the other way, 2500 to 3000 hours a year equates to a modern workweek of 48 to 58 hours per week. Which is a lot, but we have a significant number of people who do in fact work hours like that, if not greater.

That’s not to detract from the overall purpose of the post, I just think that particular stat could have used a bit more nuance or precision.

If you’re just multiplying 44×52, you’re missing the impact of holidays.

Not to out-pedant The Pedant, but is that not how you got the 2080 hours for modern Americans? 52 x 40 (8 hours a day, 5 days a week) = 2080 hours per year. 260 working days a year divided by 52 weeks comes out to 5 days a week, every week. You approached it slightly differently, but that’s how that figure shakes out.

It is true that we do have holidays, and most of us also have paid time off. My intention wasn’t to throw the overall conclusion into doubt, just that one line hit me funny.

A LOT of workers do not get PAID time off. I can personally vouch for that. I had years of employment not getting paid “holidays,” sick leave, vacation time, or any other so-called perks.

I’m not convinced that this is true. For two reasons.

If the average is 44 hours/week, that’s already accounting for holidays. That’s how averages work, after all. And it’s easy to accomplish–a couple of 50 hour weeks quickly negates the lost work hours from holidays. I’ve been in my career–a good, solid, respectable, professional career that puts me firmly in middle-class territory–for nearly 20 years and I’ve only just gotten to the point where a 40 hour work-week is normal to me. A year ago anything less than 50 felt like part time.

Then you’ve got the unpaid work of childcare, homeownership, etc., but that’s another issue.

Second, not everyone gets holidays off. Retail workers tend not to, for example–when I was working retail I got paid pretty well (for the time), but I worked every holiday. Then there are jobs where the nature of the job precludes time off. I’ve got some friends on offshore oil rigs, and “holidays” for them consist of a somewhat nicer dinner than usual; they still work. And not everyone gets the same holidays off. I deal with this constantly in my job, as access to a site when the client considers it a holiday and you consider it a work day gets thorny. And you DO NOT want folks working at power plants to all take holidays off! Or doctors, or police, or fire fighters, or even cooks and waiters/waitresses. Some of these jobs offer substantial time off to compensate (the oil rig workers get weeks off at a time), but not all of them do (doctors are notoriously over-worked, especially early in their careers).

I’m not necessarily saying that the calculation is wrong, mind you. What I’m saying is that it glosses over some very significant factors in modern society. 8 hours a day, 260 days a year should be treated as a middle-class ideal, not as an accurate representation of our society.

Which, of course, applies as much to the number of hours a Medieval peasant worked. A naive, but reasonable, assumption would be: The variability around the ideal we see in our culture is going to be comparable to the variability around the ideal we see in past cultures. Meaning that some peasants are going to work less, and some are going to work a LOT more.

Let’s not overlook the time lost to commuting! Modern wage-slaves might spend a considerable time just getting to and from their work — unlike pre-modern farm peasants. E.g., my wife and I for decades spent *at minimum* 90 minutes on the road each working day. To and fro. That adds up very quickly. It might not have been “working”, but it subtracts from your waking hours as sure as any cow-milking or wheat-threshing.

They definitely had to commute to their fields. It’s hard to generalise but a household living in a village might have many strips of land around it

True, but I would hardly consider walking to work and driving to work to be the same thing. I did not consider commuting to work to be part of work when I was walking to work–indeed i found it relaxing, but when I got sent to a different office and had to drive to work instead I absolutely started considering that part of work, because driving is stressful and dangerous.

The average one-way commute in the US is 26.6 minutes each way: https://www.census.gov/acs/www/about/why-we-ask-each-question/commuting/

And for all the discourse on second jobs, part-time work is much more common; nowhere in the developed world is the average more than 2,000 hours per employed person – the top country (Greece) is 1,893, and the US is 1,805, on OECD numbers.

Supercommuting exists and so do very long work hours, but they’re usually middle-class phenomena. For example, the infamously long hours of Japanese and Korean salarymen are for decently well-off people – the workers serving the salarymen food and drinks during mandatory after-hours company socializing don’t work these hours.

When Part II of this series was discussed, I pointed out how even the supposedly very culturally similar Nordic nations ended up with markedly different migration-related policies – as measured by the EU’s Migrant Integration Policies Index.

https://www.mipex.eu/play/

Likewise, it’s an easy, but wrong, assumption that attitudes towards work in Japan and (Republic of) Korea can be safely lumped together. If you check out the OECD link in my other comment, you’ll see that from 2010 at the latest (which is merely where the table begins) the figure of Average annual hours actually worked per worker had consistently been at least 100 hours lower for Japan than it had been for the US! In fact, in recent years, the gap has widened, so that it is now closer to 200 hours!

On the other hand, the Korean figure is nearly 100 hours greater than the American one now (and so >250 hours greater than the Japanese one) – and this is after it had declined markedly in the past 15 years! In the early 2010s, the Korean average stood in the ~2100 hour range (vs. USA’s ~1800 hour), exceeded only by Costa Rica, Mexico and Colombia*. I recall that Moon Jae-In, one of the best global leaders of the recent years, had formally restricted work week length to 52 hours, when the earlier statutory length was 68 hours, and we certainly see the effects of that change reflected in the data.

*Which has the absolute highest figures for OECD. Nowadays, they are more like Mexico’s, at ~2200 hours, but in the early 2010s, they stood at ~2400 hours, seemingly making it the only OECD economy which approached the peasant figures in this post. (In theory, it might be because of the literal peasants – though apparently, just ~15% of the workers are employed in the Colombian agriculture, which is about the same as in Türkiye – and the latter has slightly lower working hours than the US, let alone Colombia or Mexico. Of course, a very large agricultural mechanization gap could still theoretically account for that.)

Yes, working hours in Japan are on average much lower than in South Korea. But the salaryman cultures there are rather similar, including the mandatory after-hours drinks with the boss. Japan has shortened its working hours as of late, and I think Korea also has longer working-class working hours, but the cultures remain fairly similar, and this includes the need to show a lot of face time.

I would argue, in addition to what Alon Levy says, that commuting time is over-estimated because it’s not JUST commuting. When I go into the office I also run errands–go to the grocery store, pick up dog food, get the kids from school, etc. So it’s trading time for convenience: I’d rather spend 20 minutes driving to and from work, if that means I can do other parts of my job more efficiently.

A lot of the commuting discussion stems from anti-car advocates, at least in my experience. And while I agree that cars aren’t perfect and there are better options in some cases, some people are fanatically anti car, to the point where they exaggerate statistics or flat-out lie.

Not really sure what a Medieval equivalent would be. As Alex said, peasants commuted to their fields. The fields were generally scattered over different plots, so even if you were living next to one field, you’d have to hike to the rest. Maybe they’d pick up some food or fuel along the way? I know that when I was working my grandfather’s farm it was routine to grab edible plants–nuts, berries, garlic, various greens, etc. And while peasants had rights to a certain amount of wood, we shouldn’t confuse the law with the practice; if a peasant saw an opportunity to grab some extra without too much risk I don’t see them refusing to take it very often.

And since they were walking, less than 1/2 hour is not very far in terms of your commute.

Four miles an hour is an extremely brisk walk, doable by a 20th century person in good shape with next to no encumbrance. I doubt 13th century peasants loaded down with tools (you’re not storing them in the field) would do that pace.

Are all of your fields within a mile or at most two of the others? If not, then your commute is longer than the 26 minutes posted earlier as the typical American commute.

Indeed, the medieval open field system was such that peasants commuted from the village where they lived to the fields. The commute length was the limiting factor to village size. Contiguous enclosed plots with a homestead in the center are a modern innovation – colonial New Englanders lived in town centers and commuted to their fields rather than in homesteads, so this is really a post-independence innovation from the settling of the interior Northeast and Midwest.

Oofda. I’m not sure if the methodologies are the same (in fact, I strongly suspect they’re not), but ONS data in the UK about working hours puts the average at 36.6 hours a week for full time workers in 2023, or 31.8 hours a week for all workers in 2022. These figures are slightly lower than those in 2019 (32.1 hours a week for all workers), but not *that* much lower. From a cursory google, it seems the ~43 hour working week is for full time workers, so is most comparable to the 36.6 hour week stat in the UK.

These are likely to be an under-representation as they’re an amalgam of various different measures that likely don’t quite capture the extent of unpaid overtime, but even still that’s a stark difference.

If the methodologies are in any way close to comparable, you folks need to get some labour movements going pronto.

I think one reason for the difference is that US workers do not have as much annual leave entitlement as we do in the UK, which makes a difference averaged over the year (for non-UK people who are wondering it’s 5.6 paid weeks of leave per year)

“Juliet Schor’s The Overworked American (1993). The argument has been debunked quite a few times, so I won’t belabor the point here. Schor bases her estimates of medieval working hours on a 1935 article by Nora Kenyon, and a 2018 article by Gregory Clark”

I might be being dim here. is this meant to mean that Schor referenced Clarks research that she had access to in 1993 and was then published in 2018 or that she doubled down on these arguments and used Clarks data later as more evidence?

love the work

On a related note, I’m pretty sure Schor’s book is a bit older than that. Wikipedia says 1992, as do some other sources, but there’s an Amazon listing that says 1991.

https://www.amazon.ca/Overworked-American-Unexpected-Decline-Leisure/dp/0465054331

There was an issue where Schor cited an unpublished 1986 manuscript by Clark, and Dr. Devereaux couldn’t find a copy, so to try and figure out what Clark was actually saying, he used the 2018 paper Clark DID publish on the general subject. Then some wires got crossed; this has been addressed in an edited version of the main post, I think.

I know technology and yields changed a lot between Rome and early America… but I feel this calculation tells you *so much* about American history and why it might lead to a different culture than Europe, given that the standard homestead farm sizes put you firmly into the “rich peasant” category.

Most of the “weird things Americans do” (sweet tea, obsession with lawns, “A man ain’t no kinda man if he ain’t got land”, etc) basically boil down to Americans trying to live like rich Europeans in the 16/17/1800s.

@Dinwar,

Also hunting, right?

(I certainly have nothing against hunting, and greatly respect hunters, but my understanding is it was another of those things that was much easier to do in North America, at least after the great depopulation of the native population, than it was in Western Europe).

The Eastern Woodland native agriculture system primarily involved the creation of forest clearings to house a more garden-style field than Eurasian peasant systems, with corn-squash-legumes grown in tandem (overlapping but not perfectly simultaneous growing seasons) instead of a monoculture rotation. One of the main ongoing labor tasks in that native system was whitetail deer control, as these animals graze preferentially on the transitional vegetation that grows between forests and open land; deer are attracted to the clearings to begin with, then discover they are full of crops. Centuries of contact plagues took away both the crops and the people who kept the deer at bay, but all but the longest-abandoned native farm clearings simply filled with transitional vegetation and supported a much larger deer population than a fully ‘natural’ forest would have.

None of the European settlers were aware that the clearings were human-made, well except maybe some of the earliest, but there’s no indication it would have changed anything if they had understood. The ratio of deer to humans became so extreme that trade in wild-caught deer hides became steadily profitable and professionalized, which may be unique for cervidae.

And whitetail deer control is still very much a concern for farming in the eastern US, along with feral hogs.

Some parts of Europe have a similar or even bigger hunting culture than the US. In Sweden, school closes for the opening week of moose season.

I can’t find the source, but I recall a post quoting some colonial sources on how little undergrowth there was in the forests — I think one marveled that it was possible to drive a coach through some areas. What they were seeing (but not recognizing) was the result of management by the natives, and a few decades later the forests had closed up again.

For Matt Cramer: The feral hogs are winning in a lot of places. There’s a meme about it – “This is serious: a problem Texans can’t solve with guns and barbeque.”

“how little undergrowth there was in the forests”

I think Charles Mann’s _1491_ mentions that; I don’t recall his primary sources.

If the question is “was it much easier to do a lot of hunting as a North American rural settler c. 1620-1920 than as a European peasant in the same period,” the answer is definitely “yes.” The depopulation of the continent meant a lot of forest suitable for game animals to reproduce quickly, so lots of hunting.

If the question is “was hunting pursued as a prestige activity for North American settlers,” I think the answer is “mostly no,” because a lot of the people actually doing that hunting were hunting for sustenance or as fur-trappers for whom that was their livelihood.

@SimonJester,

I wasn’t suggesting that hunting was a prestige activity, I was suggesting that it became very culturally significant (and remains culturally significant to this day in states like Pennsylvania, Michigan etc.). And, yes, it’s of course for food, but something can play both an economic and a cultural role.

@Matt Cramer,

That’s fascinating about schools in Sweden! I’ve heard about schools in the US taking a day off for the first day of deer season (and from personal experience, in some parts of Michigan, even if they don’t officially take a day off a lot of students are absent that day anyway).

I was thinking specifically about western Europe, so i can definitely believe that Scandinavia and Eastern Europe might be a different story.

Making people richer is not the same as changing their culture. What might change the culture is a less intense competition for land. It would be easier to escape the domination of the local Big Man. But remember there was a lot of land per person in the Russian Empire, and that did not end up, socially, much like the US or Canada.

It might be interesting to draw comparisons with Argentina. Or Quebec.

Possibly culture (as in, Protestantism plus Anglo-Saxon liberty plus parliamentary democracy) is as important as the material conditions of production. Although, to be honest, my crypto-Marxist tendencies usually lead me in the opposite direction.

Interesting. My natural tendency is to over-credit those very things for American success, so I try to downplay them as much as possible in my head to correct. But I’m a classical liberal/libertarian who’s determined not to get trapped by thinking I have all the answers.

I wish the answers could at least occasionally not be “It’s even more fiendishly complicated than you already think it is.” Then again, this blog wouldn’t exist if that weren’t generally true…

People have in earlier comment threads brought up the subject of life-cycle servants in Northern Europe. Presumably such a system, in which people are *expected* to leave the family farm as soon as they can do useful work, would be better suited to opportunistically expanding over any aborigines on the frontier.

IIRC there is something in de Tocqueville where he compares the faster spread of Anglo, rather than French Canadian, settlers throughout North America.

Russia and similar (Hungary, Poland) had to keep control of the peasantry to maintain the state structure – the surplus extracted afforded an army, bureaucracy, court etc. Without which they would be demolished by the Tatars/Swedes/Germans/Ottomans – or each other. The US had no need of a strong state, given that it faced no similar level of threat.

Note that for all its Protestantism and ‘Anglo-Saxon liberty’, Britain was one of the tightest states in Europe – high taxing and very stringently governed.

“Russia and similar (Hungary, Poland) had to keep control of the peasantry to maintain the state structure – the surplus extracted afforded an army, bureaucracy, court etc.”

Russia and Poland are nicely similar and contrasting, Russia for strong court and bureaucracy, Poland for weak court and bureaucracy.

But BOTH Russia and Poland relied heavily on “light cavalry” lower nobility armies. This meant that both had to allow serfdom – the peasants were not themselves able to serve as light horse, so the state had to back petty nobles and give them the tools to squeeze the peasants hard, to support a light horseman with as few serfs as possible, rather than spread the load lightly across a bigger number of free tenants.

The contrast is the tools of state the petty nobles ended up backing. Both Russia and Poland featured suspicions between light cavalry and heavy cavalry. In Poland, eventually the light cavalry and heavy cavalry agreed on collective institutions to make the prince weak and elective – and likewise in Novgorod. In Moscow, the autocracy enjoyed the support of light cavalry who suspected that collective institutions would be hijacked by heavy cavalry.

You ought to specify the history period are you talking about. The core of the Ruthenian forces in the medieval, the druzhina, most certainly was heavy cavalry (though they often fought as dismounted infantry depending on conditions) – as heavy as the Crusader knights, for one. Here is a video from a Russian museum about the Kulikovo Field battle of 1380, with the guide’s voiceover accompanying the reconstructions.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gnzNqp9IAWc

Around the third minute, you can see stirrups (such an archetypal feature of heavy cavalry there is even a literal “stirrup hypothesis” about their role in the emergence of “feudalism” – albeit one our host disregards) while the guide mentions spurs as well, and says that with those two, they were fully capable of the same shock charges as the European knights. From the fifth minute onwards, armour is shown in detail – which for the elites was a coat of plates with thin chainmail underneath. This is basically the same as what many of the contemporary knights actually wore – our host frequently pointed out in early posts that plate armour had evolved much later than most people think. From the wiki:

So, the only difference is that plate armour was never adopted in Ruthenia – in large part because it so was quickly rendered obsolete by firearms, which spread much faster there than most people assume – the first firearm in Russia is dated to 1389, and Ivan the Terrible was reported to have ~2,000 cannons spread around various cities. This spread of firearms also rendered heavy cavalry irrelevant – which was another reason why Ivan the Terrible foolishly thought it safe to purge the heavy cavalry class, the boyare with oprichina after he conquered the Kazan and the Astrakhan Khanates. (Which ended up massively weakening the state, causing things like the Swedish advances into future St. Petersburg territory, the final Tatar raid on Moscow mentioned by Hastings and the assassination of the last Rurikid, Ivan’s the Terrible underage son (the remaining heir after Ivan had notoriously beaten his elder brother to death in a fit of rage). Altogether, this had spurred the state’s collapse into the notorious “Time of Troubles”, as demographically devastating as any other major 16th-17th century conflict, with double-digit population declines.)

I suspect his purge of the powerful boyare in favour of larger numbers of comparatively weaker and more state-dependent lower nobility (dvoryane) might be what you are referring to – though you have written it in such a vague manner it’s hard to be sure. Afterwards, though, it is certainly true that the cavalry sourced from such lower nobility classes (most notably the gusary – a Russian adoption of Polish hussar) certainly enjoyed far more prestige during the Imperial Russia than any sort of infantry besides the grenadiers (which had the role of royal guard formations.)

“and the assassination of the last Rurikid, Ivan’s the Terrible underage son (the remaining heir after Ivan had notoriously beaten his elder brother to death in a fit of rage)”

Not true.

The remaining heir was the middle son, Fyodor Ivanovich, 24 when the elder son was killed, 26 when Ivan died, 33 when his little brother Dmitry perished – and he survived the first public death of Dmitry in 1591.

Either Fyodor (if Dmitry died in 1591) or Dmitry (if his first apparition was real but his second was not) may have been the last Danilids, but they were definitely not the last Rurikids, nor even the last Rurikid czars.

By 1598, the title of “prince” or even “Rurikid prince” carried little clout above that of non-prince boyar – but the czars did not give out the titles. There were a lot of Rurikids available in 1598, but Godunov was elected (and was not one of the Rurikids). In 1606, a Shuiski got the throne – and WAS the last Rurikid czar. In 1613, there were still many Rurikid princes available – Prince Pozharsky, for one – but it was Romanov, again a non-prince, who was elected.

“Britain was one of the tightest states in Europe – high taxing and very stringently governed”

Not to make a moral point, but British taxation was incomparable to Continental taxation as it actually funded public goods (sometimes pretty much the same things we’d consider public goods, sometimes things that pre-modern people considered public goods, eg religious offerings) and paid a professional army.

In most Continental system, you paid your taxes to the state, got at the very best security (but in general much worse than the one enjoyed by the British) and everything else – roads, churches, stockpiles – was paid either by the local nobility with additional taxes, or by the village (and you were expected to contribute oc). Oh, also, if there’s a war you or your son will be pressed into service.

I don’t want to do the math rn, but it’s pretty easy to put a pecuniary value on military service (because richer people paid to send a substitute), and if we add village “contributions”, I’d be really surprised if most continental subjects were taxed less than the British ones.

“Local Big Man” arises in part when the Small Folk perceive the need for his protection. While the “Indian frontier” was certainly violent in North America, a heretofore unprecedented aspect of it was that even the Small Folk had individually possessed firearms, and so routinely possessed the capacity to inflict sufficient casualties on tribal attackers to frequently make even a tactically successful raid strategically pyrrhic.

In contrast, there was no such disparity between the peasantry in Moscow Knyazhestvo/Russian Empire’s heartlands and the raiders assaulting them – and the latter were enough of a threat that for nearly a thousand years, countless trees were regularly cut down and formed into the abatis obstacles (засеки) – with the most important one compared to the Great Wall in terms of its extent!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Zasechnaya_cherta

You do not build and maintain such without the prominent Big Men – and like our host just wrote, they then demand great taxes, so while you might have a lot of land by Western/Central European standards (one source suggests allotment sizes around the time of serf emancipation in 1861 actually were at ~35 acres per household), that already brings household position well down. Then, we have discussed firewood the other week – peasants in warmer areas both required less of it, and were able to obtain a lot of comparably easy-to-harvest branches via coppicing. Neither was true at the latitudes where the dominant forests are coniferous (and therefore un-coppiceable.) This adds labour hours, and also means that your ability to spread out geographically can be tied to firewood supply in addition to the other factors discussed above.

I’ll also note that while some might be tempted to look at the nominal land area of the Russian Empire and think that it represents land easily available for the peasants, this would be rather misleading. After all, as many posts on here have noted, land travel in the preindustrial times is difficult and expensive. (Not to mention liable to kill via the diseases of poor hygiene.) A peasant at a crowded village in the heartland might have heard rumours of sparsely settled land a few hundred km northeast, but how are they going to safely get their family and possessions there?

There are studies showing exactly that! Combination of high threat requiring highscale mobilization and tying down manpower. The Tartars sacked Moscow in 1571. The last big raid to reach the Oka valley was in 1633! Rates of serfdom were *much* higher in the 1600s near the Zasechnaya cherta than in the rest of Russia. Peter ‘the Great’ and Catherine ‘the Great’ then did a lot to broaden and strengthen serfdom in the 1700s.

The Native American threat gets frankly seriously overrated outside the early colonial period. The French and Indian War was the last time you really had a conflict that could be called demographically significant on the frontier as a whole. In a macro-sense we barely even had to try to defeat the Natives. The US fielded about 3k men for the Great Sioux War. The two sides in the Civil War raised *400* times that at peak. Main benefit of US Army is it greatly reduced settler losses compared to pre-Revolution. But the settlers could have ground forward without them.

Well. I would add the wars of both Pontiac and Techumsah as demographically significant, but the latter ended with the war of 1812, so your point still stands.

Well, the foreign threat level to Russian peasants may have been higher than that to American frontiersmen, but as people have observed, that is not saying much. You could say that about a lot of people in the Old World. It was old, and mostly had time to reach technological equilibrium.

Certainly, it is not obvious that the threat to them was greater than that to the Cossacks further south. I don’t really get the impression that the Cossacks were reduced further into serfdom.

I gather from Azar Gat, and indeed our host and advisor, that a need for military effectiveness tends to produce greater equality among the militarily important sectors of the population. Whatever happens, the people who provide the musketeers/ rowers/ heavy infantry/ cavalry/ whatever-it-is-you-need have to be treated well. In Russia it always seems that the people who need to be treated well are the Oprichniki/ Okhrana/ KGB / FSB.

A cynic might say that the Grand Dukes of Muscovy were not the Golden Horde’s enemies but it’s tax collectors. That’s why they needed collaborators more than soldiers.

And these days, the ruler of Muscovy has an end-the-world button, and even less need of an effective army than usual.

The cossacks in this relationship are (basically) military settlers, and just like other military settlers they sometimes get into conflict with the central government, but the point is they aren’t socially really much like the peasantry either: There’s a reason “cossack” become a byword for oppressive enforcerer of authoritarian regimes.

Your narrative is really badly warped by what we shall politely call presentism.

For starters, the Golden Horde existed from 1224-1459. It actually is true that the contemporary Muscovite rulers had collected tribute to the Horde for most of its existence – after Moscow had initially resisted and got razed in 1238 alongside over a dozen (then)-major cities across modern-day Russia and Ukraine. (In fact, a major reason Moscow, which was only founded a century earlier, was able to assume a dominant position over the cities that had existed for centuries longer was due to the levelling effect of 1238, which had erased the enormous advantage Kiev* in particular had enjoyed until then, leaving the relatively remote Novgorod as the only major rival.) It also certainly wasn’t all they did – in 1380, Князи of Moscow and Vladimir have exploited an intra-Horde civil war to take battle to one of the claimants, Mamai, at Kulikovo Field, resoundingly defeating his forces (only for the other one, Tokhtamysh, to consolidate power and raze Moscow again.)

More to the point, there were no опричники during that entire period – because they were formed by Ivan the Terrible in…1565! All the previous Князи** – be they from Moscow, Vladimir, Novgorod, Kiev or Chernigov (northern Ukraine, and another place which never truly went back to its pre-1238 importance) had a very similar military system, which relied on the дружина, the kind of well-armoured “mounted warrior-aristocrats” (to use the our host’s terminology) not overly different from the contemporary European knights militarily or socially. In line with Gat, they certainly were treated well – but of course, they (generally) had to be the Big Men whose estates would support the cost of their armour, horses and training – so their peasants got soaked for the sake of all that. This system worked well enough for battling each other or giving major battles to pre-Horde nomadic tribes – it simply broke down all at once in their face of the Horde’s excellence (not unlike how the hoplite-centered system of all the Greek poleis had almost simultaneously crumbled in the face of the Macedonian phalanges.)

In fact, what makes your claims particularly ironic is that not only were the опричники formed well after the Golden Horde stopped being a threat***, but that they were also created as the structure of the Muscovite force became more egalitarian than ever before – the дружина ceased to exist (in no small part because опричники purged so many of the boyare it would have been comprised of) and the core of the fighting force were instead стрельцы, the unarmoured infantry with firearms and axes. It was with this new system that Ivan the Terrible was able to both utterly raze Novgorod, forever removing it as an alternate centre of power and to conquer two major remnants of the Horde – the Kazan and the Astrakhan Khanate, which have remained as core Russian territory ever since. So, the claim that any Muscovite ruler had prioritized опричнина over the regular fighting forces because they expected to collect tribute instead of fighting is completely, utterly backwards in just about every single way imaginable.

As for the Cossacks, they may not have been “reduced further into serfdom”…because by and large, the early Cossasks were runaway serfs in the first place! Ones who had initially intermarried with половцы, the proto-Tatars (also known as Cumans further west – a name Kingdom Come: Deliverance players ought to be very familiar with) – after all, the word itself appears to have originally meant “exile” in the latter’s language! Thus, they have also taken up their semi-nomadic ways from them, but it had taken them a while to form as a distinct group – the first historical references to them as an entity (rather than Turkic texts calling any exile “a Cossack”) appear to date to ~1400s – only a generation or two before the Golden Horde as a whole collapsed.

After that, as was already pointed out by Arilou, they fairly quickly settled into the role of enforcers of the Russian state at its frontiers. In fact, the bargain they struck, exchanging relative independence (including the right to exclude any and all Jews from their lands – just so that we avoid any excessive romanticism here) for the 20-year conscription of every single fit male appears completely in line with your “I gather from Azar Gat, and indeed our host and advisor…the people who provide the musketeers/ rowers/ heavy infantry/ cavalry/ whatever-it-is-you-need have to be treated well.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Cossacks

*Apparently, Kyiv did not become the local spelling until much later.

**I am excluding the major Belorussian ones (mainly Minsk and Polotsk), since they have been under Lithuanian influence and were spared the Horde’s 1238 rampage, which might have also resulted in a divergence of their military system.

***- to the point that Ivan the Terrible’s father had razed the capital of the largest splinter still attempting to piece it back together, the Grand Horde – by pinning the bulk of their forces at the Ugra River without giving them a fight, while a side deal with the Crimean Khan ensured that the latter’s troops would block the Horde’s Polish allies from intervening. Mo

“Your narrative is really badly warped by what we shall politely call presentism.”

YARD, if we are talking about me, I can say what politeness prevents you from saying and call myself ignorant. Which I certainly am about Russian history.

I am just unconvinced by the idea that all the slavery/serfdom is a consequence of the low population density, given the comparison with North America. And I am unconvinced by the idea that it is a consequence of the greater military threat, given the comparison with countries in Western Europe e.g. Holland.

I think your point about the importance of light cavalry has a lot to commend it. It would help explain why everyone was so happy to step on the peasantry, a non-light-cavalry-producing class. And the difference with the West, where infantry were generally important.

@ad9: Honestly, I don’t think a person truly ignorant of Russian history would have written what you did. I.e. they would have simply not known what oprichnina is in the first place, for one. You, however, had picked four examples – “Oprichniki/ Okhrana/ KGB / FSB” – and claimed that they represent some universal law of Russian history in spite of only covering a very small fraction of it. This sort of overconfident grand-narrative making could seemingly only arise after exposure to a certain set of political narratives from the recent years – but the net effect is akin to that notorious claim, “Fox News viewers know less than those who do not watch news at all.”

As in, the recorded history of Rus’ (sometimes known as Ruthenia in the European languages) dates to about 862. Even if you want to limit the timeline to Moscow’s founding specifically since Rus’/Ruthenia was mainly governed from Kiev (never mind that Novgorod and other then-powerful and always territorially Russian cities like Pskov are even older), that still starts us off in the mid-1100s – 400 years before oprichnina, which is historically situated well into the “Early Modern” period, rather than any definition of Medieval, which this series is (mostly) about. It had also existed for only a dozen years anyway – in large part because the destruction they wrought had directly precipitated the end of the Rurikids and the state’s onetime collapse into the “Time of Troubles”.) Then, you skip forward another 300 years and only cover the most recent 150 years or so, as the (informally called) okhranka was founded in 1866 – in response to all the assassination attempts on Alexander II, who had just abolished serfdom five years earlier. (Though in a very half-hearted manner which generally burdened “the liberated” with debts and often caused them to sell their plots to former masters.)

So, your initial narrative does not really match the facts at all. Now, someone with the more comprehensive knowledge of this history could have had advanced a more plausible version of this argument – i.e. the aforementioned Rurikid dynasty consisted of the Norse elites recorded to have been invited to rule with the words “Our land is great and abundant, but it lacks order.” (Of course, many have argued that we have no way of knowing if this wasn’t invented to whitewash a simple Norse conquest not wholly unlike that of William the Conqueror. Though even if taken at face value, the fact that the Rurikids have mostly ruled from Kiev is…not very convenient to present-day political narratives.)

Wait, the same North America which had imported vast numbers of literal slaves? What happens to your comparison once they are accounted for?

What about Holland? I haven’t studied its history specifically, but a cursory look at Wikipedia just now certainly does not seem to suggest it went through nearly every major population center being systematically razed in the 13th century – which is exactly what happened in the Ruthenian lands in 1237-1241. It does mention frequent Viking raids over the “defenceless” towns in the 700-900s; however, I really doubt the Rurikids would have been “invited” to rule in 862 had there not already been a history of similar military dominance of the Norse. If you instead mean the Eighty Years War – well, the aforementioned Time of Troubles took place during that period and was at least as demographically devastating, if not more so.

If anything, the main reason to invoke Holland is because it had been the main inspiration for Peter the Great – to the point that he literally created the Russian flag of the then-and-now by tearing the Dutch one into strips and rearranging them! Peter the Great modernized the military from Ivan the Terrible’s times by bringing many Dutch and German officers into it, and this had continued for the rest of century (since the lover of Peter’s niece and de facto (co)-ruler was Latvian German, and then of course Catherine the Great was literally the German wife of Peter the Great’s half-German grandson). Their influence was in everything, from uniforms to terminology (i.e. the Russian army still calls its corporals efreitor) and most notoriously, the discipline. (I.e., “running the gauntlet” was adopted from them, and the thin wooden lash given to soldiers in the gauntlet was called another German term, Spitzruten.) It was also during this period that the serfdom became at its most severe and restrictive (i.e. before the Time of Troubles, there had been a Yury’s Day tradition where serfs were legally allowed to change their masters during that one day).